Putting Rural Wisconsin On The Map

Rural America and the issues faced by people who live in rural places are at the center of the national conversation. But once you go outside of our major cities, exactly what places are considered rural?

May 16, 2017

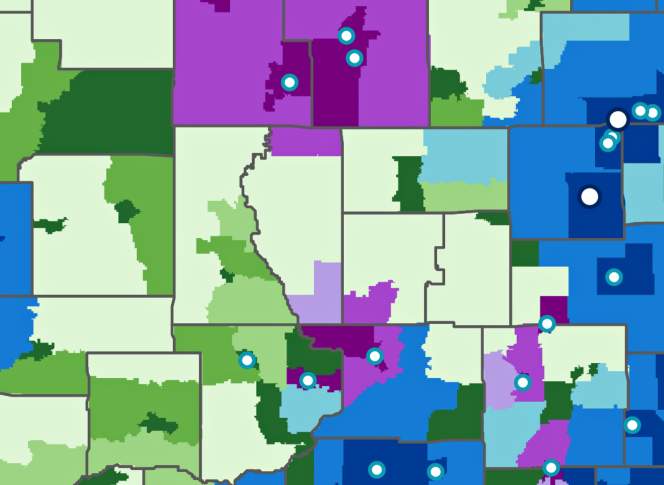

Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes map of Wisconsin crop

Rural America and the issues faced by people who live in rural places are at the center of the national conversation. In large part, this interest emerged after the 2016 presidential election, when Donald Trump won the electoral votes of Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania. As is the case around the nation, interest in rural perspectives on national issues is keen in Wisconsin, which surprised the nation — and many residents of the state — when its electoral votes went to the Republican presidential candidate for the first time since 1984.

Post-election analysis has focused on the “rural vote” in Wisconsin and other states, where voters who don’t live in major cities heavily influenced the outcome of the election. But once you go outside of these cities, exactly which places are considered rural?

It’s a matter of conventional wisdom in Wisconsin and across the U.S. that rural places are socially and culturally different from urban and suburban areas. But it’s helpful to examine how rurality is officially defined to explore its many dimensions.

When it comes to specifying rural areas on a map, demographers and social geographers use a variety of definitions. In some cases, any place that isn’t a major metropolitan area, including small towns and even smaller cities, is defined as rural. But it also refers to very remote locations, with no population center or barely any people living there at all.

There are two very common definitions of rurality used in demography. In each, rural is defined in terms of all places that are not urban. Therefore, a definition of what determines urban places is required to define their rural counterparts.

Defining urbanized places

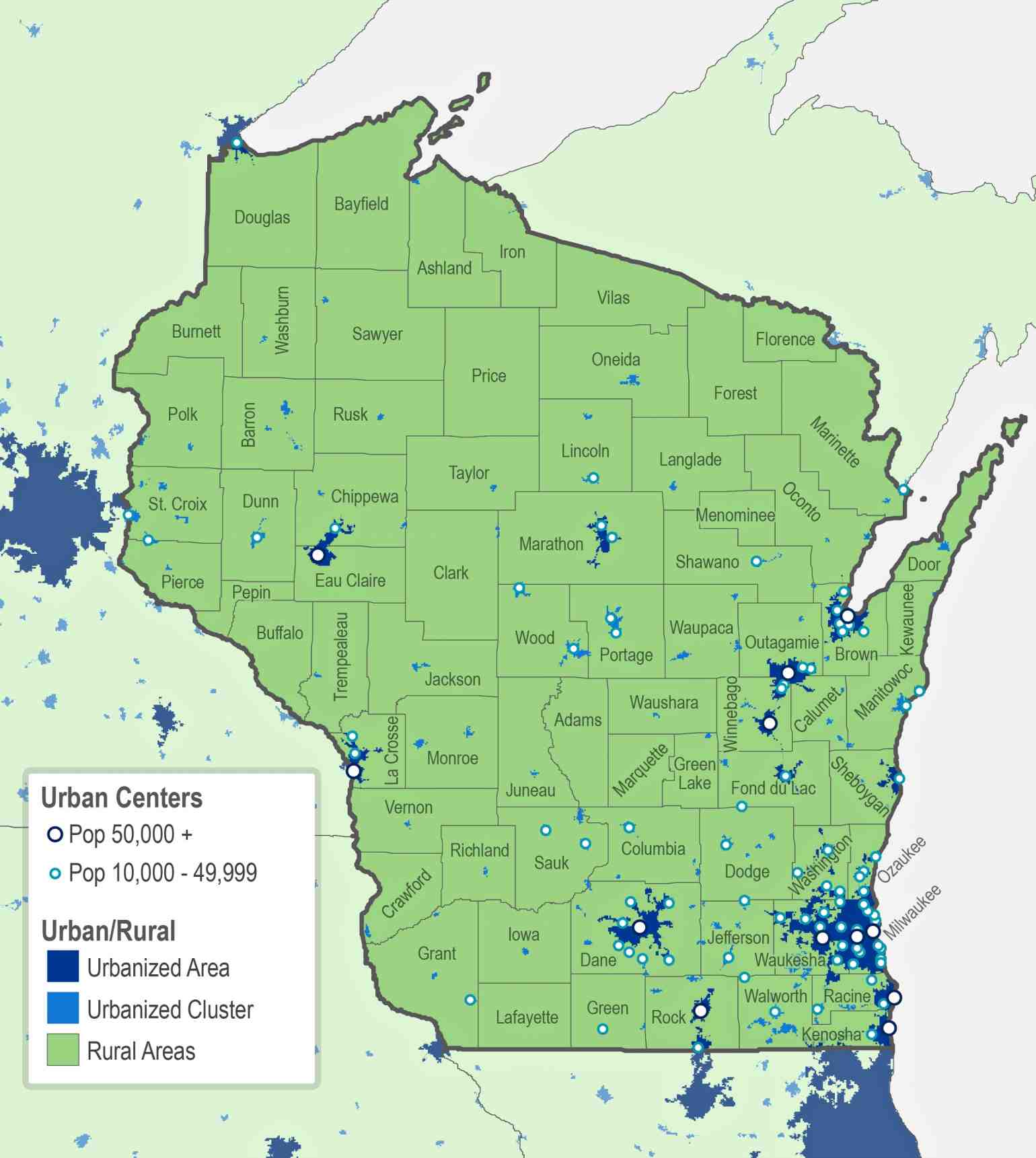

The U.S. Census Bureau identifies two different kinds of urban areas: “Urbanized clusters” with 2,500 to 49,999 residents, and “urbanized areas” with populations of 50,000 or more. For both of these definitions, population density — or the number of people per square mile — is the most important marker of urban status. All non-urbanized land area — any place that isn’t part of a city or town of at least 2,500 people — is considered rural.

The map of urban and rural places developed by the Census has a very fine level of detail. That focus means there can be both rural and urbanized places within a single county. In fact, nearly all of the counties in the United States include both rural and urbanized areas. A tiny fraction of counties that overlap major cities, like New York and Chicago, are 100 percent urban. On the other hand, 23 percent of all U.S. counties contain no urbanized areas.

By the Census definition, 97 percent of Wisconsin’s land area is rural, but only 30 percent of the population lives in rural areas.

Jen Whitty is a University of Wisconsin-Extension educator based in Waukesha County, which includes a large urban center and a considerable urbanized area, along with adjacent rural areas. She grew up in rural Iowa.

“Oftentimes, when you live rurally you have to explain your hometown by proximity to the nearest metropolitan area,” she said.

The major urbanized areas in Wisconsin (shown in dark blue in figure 1) include the Milwaukee, Waukesha and adjacent areas, Racine and Kenosha, Madison, Janesville and Beloit, Sheboygan, Green Bay, Appleton, Oshkosh, Fond du Lac, Wausau, La Crosse, Eau Claire and Superior.

Metropolitan, micropolitan and non-core

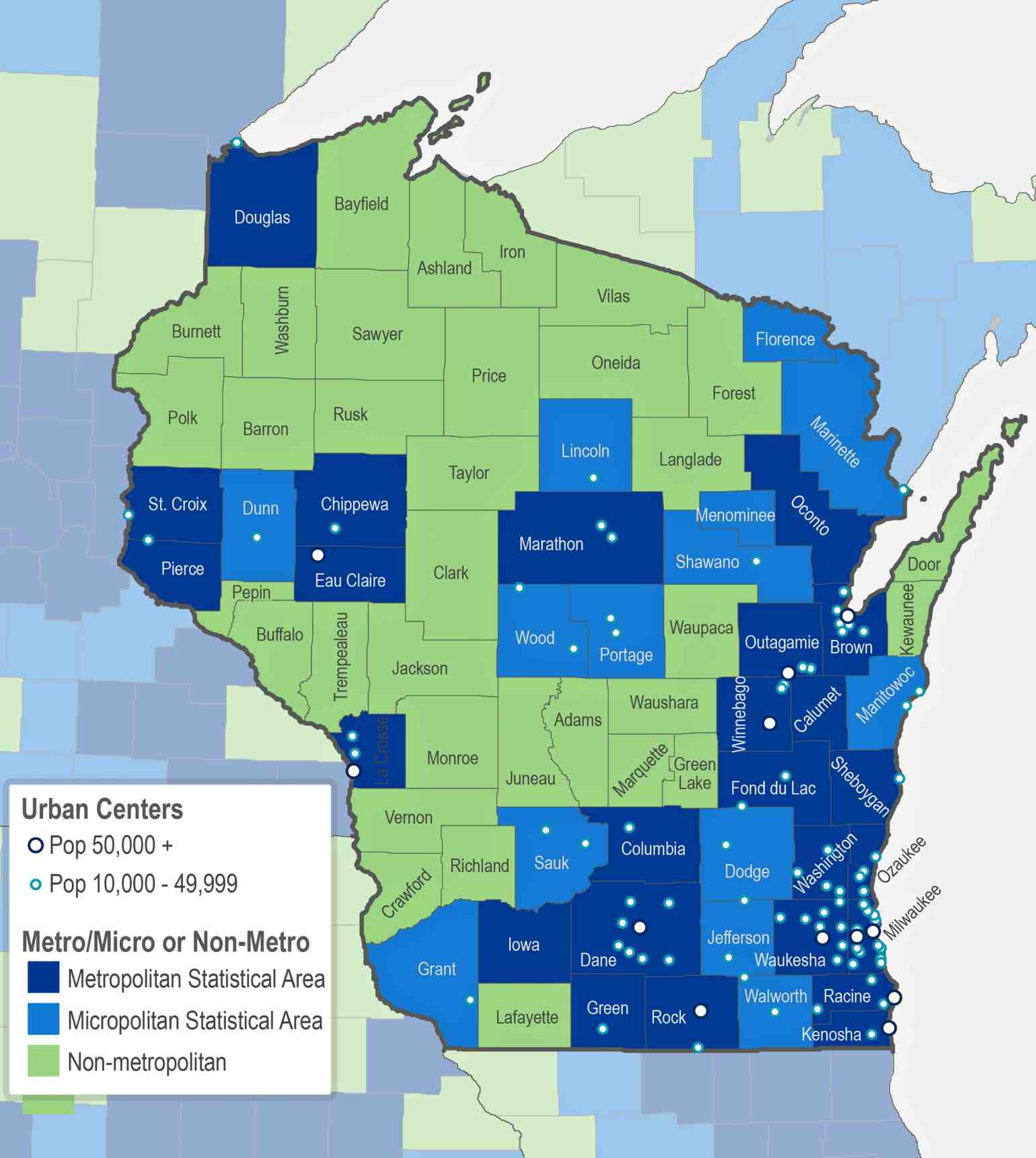

The U.S. Office of Management and Budget defines rurality in terms of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas, often called “metros” and “micros.” These can be single counties or groups of counties, but either way, they are entire counties with a unifying core city.

Any county with a city of at least 50,000 people is designated as metro, as well as any neighboring counties that are economically and socially linked to it through people commuting across county lines. The micro designation applies to counties with a smaller city center of 10,000 to 49,999 people, including neighboring counties with a significant number of commuters. Counties that are neither metropolitan nor micropolitan are considered rural or “non-core” by the OMB.

This higher threshold of urbanicity compared to the Census definition results in many smaller cities of up to 9,999 population being classified as rural. For example, Monroe County is considered rural, even though its county seat, Sparta, is an urbanized cluster housing 9,638 people, based on 2015 estimates from the American Community Survey.

Since metro and micro designations are made at the county level, within many of these areas there are places that might be considered “rural” at a finer scale. Calumet County is included in the Appleton metropolitan area because its northwestern quadrant houses some suburban areas, but the remainder of the county is much less urbanized.

Within Wisconsin, 32 of the 72 counties are rural according to the OMB definition. Compared to the Census definition, 49 percent of the state’s land area by square miles is considered rural, and includes 13 percent of its population.

Meanwhile, some Wisconsin counties belong to a metro area that crosses the state line. For example Pierce and St. Croix counties are part of the Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington metro area because a fair number of their residents commute to the Twin Cities to work. Similarly, commuting traffic near the state line with Michigan’s Upper Peninsula links Florence County to the Iron Mountain micro area.

Commuter connections

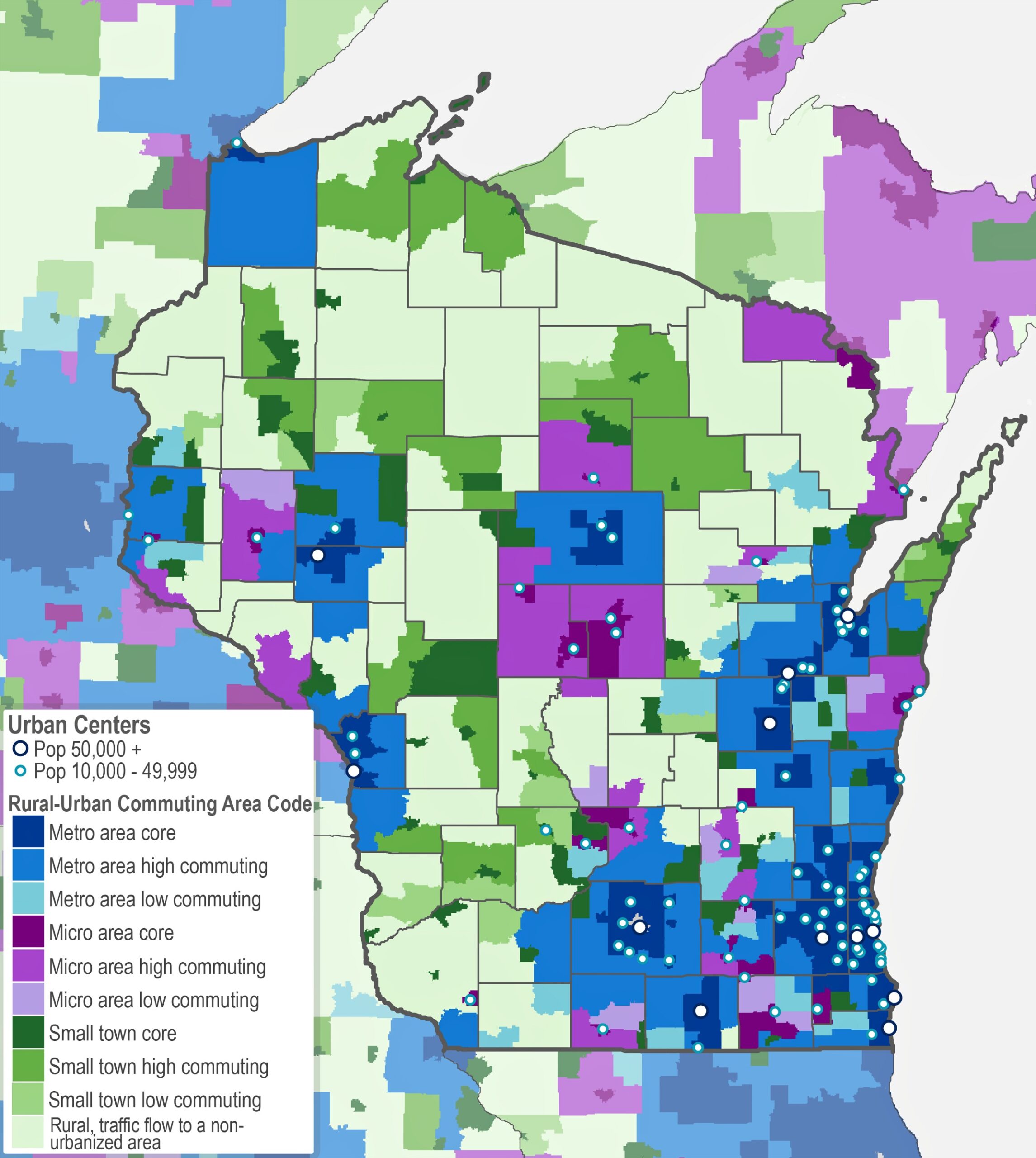

The U.S. Department of Agriculture maintains several different classification systems that capture different dimensions of rurality. The Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes offer sub-county level geographic detail to help understand dimensions of rurality in more local terms. Like metro and micro statistical areas, RUCA codes measure population density, urban population size and the percent of people that routinely commute to another place. However, the smaller geographic unit of census tract is used for measurement, providing a richer and more nuanced set of definitions.

As detailed by the USDA’s codes, the most rural places have low population density, and most commuters are destined for areas that are also non-urbanized. Areas with low population density but a high number of commuters bound for towns, smaller cities or large cities are classified as commuter areas.

In Wisconsin, rural areas with very few city or town-bound commuters comprise 38 percent of all the land area and just 8 percent of the population.

Compared to metro area Census tracts (shown in shades of blue in figure 3), the most rural tracts (the lightest shade of green) are also substantially older — the combined median age for the three metro RUCA codes is 37.2, while the median age for the rural RUCA code is 44.4 years.

Aging is an important dimension of rurality, noted Myles Alexander, an educator with UW-Extension Oneida County. Aging in rural communities presents an important challenge for planners and service providers, including when it comes to the provision of health care. In fact, the federal government supports additional healthcare personnel with a combination of programs in places designated as healthcare shortage areas.

The Wisconsin Office of Rural Health works to build healthcare capacities in the state identified as having a shortage of primary health care options. The office also published a report in February 2016 that examines the definitions of rural and urban areas in Wisconsin.

Remoteness and access to services

Another USDA rubric identifies areas that are not just rural, but remote as well. The Frontier and Remote Area Codes (FAR) classification system identifies these places based on estimated drive-times to a city. Distance from any urban center may make it difficult for residents of remote areas to access goods and services.

Frontier and Remote areas are placed into four classes, with level 4 being the most remote. Most of the people living in these zip codes are at least an hours’ drive from a major city and 15 minutes away from the nearest community of at least 2,500 people. Due to these distances, residents of “FAR” places may have difficulty accessing food, health care, car repairs or other basic goods and services, particularly if they have limited resources or mobility.

The USDA’s zip-code level system identifies a large portion of northern Wisconsin that is classified as Frontier and Remote areas — indeed, much of Burnett, Sawyer, Price, Ashland, Iron, Vilas and Forest counties are FAR level 4 (dark green in figure 4).

This metric uses drive-time to a city to measure remoteness, but Steve Nelson, a UW-Extension educator in Forest County, suggests a different measure that speaks to the quality of life that draws people to remote places, in spite of the lack of services.

“Rural equates to places with an average decibel level lower than 50,” he said. “Did you know the hum of a mosquito is 20 decibels? Quite bearable compared to the constant noise in urban areas.”

There are also smaller FAR areas in the central and western parts of Wisconsin, including in southern Crawford County near Prairie du Chien, which was one of Wisconsin’s earliest European settlements. It’s designated as FAR level 3, which can include smaller urbanized places up to 10,000 people, but which are still more than an hour’s driving distance from large cities where some services, such as specialty medical care, would be available.

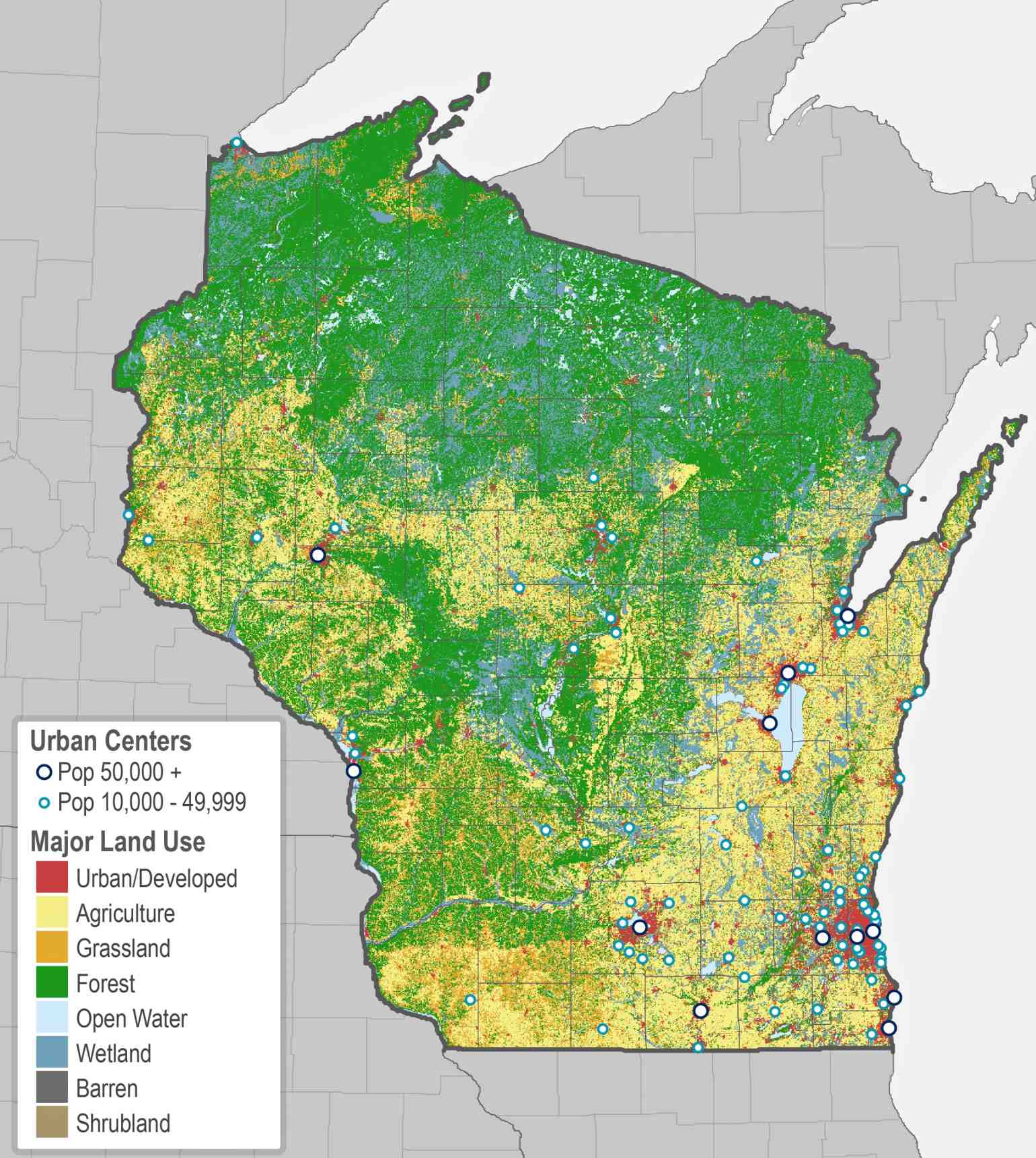

Types of land use

Major land uses are an important measure of rural economies. A Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources map illuminates the role of land itself with rich geographic detail. Rural areas are often thought of as farmland, pasture, woods or other wild areas, and these land uses directly relate to rural economic activity: agriculture, lumber, fishing, foraging and tourism.

The major land uses in Wisconsin are color-coded in the DNR’s map (figure 5). Forests (green), grasslands (orange) and wetlands (blue) abound in the northern third of the state, and extend into much of central Wisconsin. Agricultural land (yellow) occupies much of southern and eastern Wisconsin, as well as major areas in central and western parts of the state. Urban and other built-up lands are easy to spot in red, with by far the largest area (by land mass as well as population) in Milwaukee and its suburbs. Other larger urbanized areas appear in red in Madison, Green Bay and the other Fox Cities, and elsewhere around the state.

Cows and deer per capita

Five definitions, five different versions of “rural Wisconsin.” It is very clear that the North Woods are by and large rural, and Milwaukee is urban in every definition. But what about places where urban and rural intersect?

In southwestern Wisconsin, Iowa County has very little urbanized area, yet it is part of the Madison metropolitan statistical area. The USDA’s Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes show that the county is split — its eastern half has close commuting ties to Madison, while its western half is quite rural, with commuting ties to Dodgeville, an urbanized cluster that does not meet the micropolitan statistical area population threshold. Yet no portion of the county is considered “Frontier and Remote.” Which definition is best?

“Compared with other ‘rural counties,’ Iowa County exists in two worlds,” said UW-Extension educator Gene Schriefer, who is based in Dodgeville. “We have low population density and more cows than people, yet a large swath of the county population commutes and has ready access to metropolitan amenities, and some areas have very limited access. I see us as an interface county, where urban [and] rural meet and sometimes collide, with different goals, values and expectations.”

The cow-to-person ratio is an oft-cited measure of rurality that’s worth a closer look. Cows do indeed outnumber humans in Iowa County, and in much of the western half of Wisconsin where dairy farming is a major land use and economic activity. In the state’s more northerly counties, cows are fewer in number, but are replaced by relatively large populations of deer.

Defining rurality through density

Rural is not simple to define, perhaps because the real question is rural for what purpose?

Each definition serves a different purpose. Metropolitan statistical areas were developed to facilitate standardized reporting on population characteristics, such as in U.S. Census and federal unemployment data. RUCA codes identify places that are economically connected to urban centers and thus benefit from those economies. FAR codes are intended to identify areas where residents may be cut off from key services such as broadband internet access and emergency medical care.

One universal is that rurality exists on a continuum. A simple map of population density captures the concept of a spectrum between urban, suburban and rural places in Wisconsin. Though rurality has many dimensions and can mean different things in different places — distance to services, land use, community, cows — one commonality is that rural places have low population density.

“Rural areas are vastly different but probably have at least the one common characteristic of a sparse population,” notes UW-Extension Vilas County educator Chris Stark.

In all definitions of rurality, Wisconsin has a large rural-dwelling population and a large amount of rural land area compared to many other states. Moreover, the urban centers in Wisconsin are, relatively speaking, quite small. Although Milwaukee is a major metropolitan center, its population size does not overshadow other urban centers in Wisconsin, unlike neighboring Illinois and Minnesota, which are dominated by Chicago and the Twin Cities, respectively, in terms of population and their economies.

Wisconsin’s economy has long been reliant on agriculture, manufacturing and resource extraction, which are unique in that they are often sited in rural places. UW-Extension Oneida County educator Myles Alexander notes that some rural places may rely on both resource extraction and tourism, which can create tension between productive land use and conservation.

Cultural and political divides between rural and urban America have received major national attention in the wake of the 2016 election. This interest is reflected in the skyrocketing success of James David Vance’s ethnographic account of rural America in his book Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and a Culture in Crisis, a #1 New York Times Bestseller that was named the UW Go Big Read book selection for 2017.

In her 2016 book, The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker, UW-Madison political science professor Katherine J. Cramer suggested another definition of rurality — a sense of place, history, and community. As she describes it, rural is not a place but an identity.

Cramer’s description of rural Wisconsin contrasts with most of the demographic definitions because it focuses on characteristics of rural-dwelling people, including their social values and political perspectives, and not the characteristics of rural places. Some of the statistical definitions focus on where people are living and working, such as population density or commuting patterns, but this information does not focus strongly on social aspects of rural life.

Figuring out exactly which places are rural is challenging because rurality is truly a multidimensional concept. Land use, economic activity, population density, commuting patterns, distances to cities, access to services, demographics, and localized culture and politics all contribute to a place being perceived as “rural.”

Rurality seems to be a relative term — it’s not a black and white issue, but exists on a spectrum across many dimensions.

Editor’s note: The report was updated with additional information about the work of the Wisconsin Office of Rural Health.

Malia Jones is a social epidemiologist with the University of Wisconsin Applied Population Laboratory who studies segregation and its health consequences. Mitchell Ewald is an intern with the UW Applied Population Laboratory.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us