Public Health Officials In Wisconsin Struggle With Gaps In Substance Abuse Data

Data about substance abuse is plentiful. The difficult part is pulling together all that information, analyzing it, and identifying the patterns.

November 2, 2016

Opioids and data illustration with fentanyl molecule

People across Wisconsin and the country are collecting a lot of information about substance abuse. Coroners and medical examiners document overdose deaths, hospitals and treatment centers admit patients with substance-abuse issues, police file reports on drug-related incidents. Many public high schools anonymously survey students about drug and alcohol use. Data is plentiful.

The difficult part is pulling together all that information, analyzing it, and identifying the patterns.

“When the data are analyzed and published, it’s a year and a half or two years out,” said Theodore Cicero, a professor of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis. “You can say, ‘we have a problem, but it’s been with us a couple of years.'”

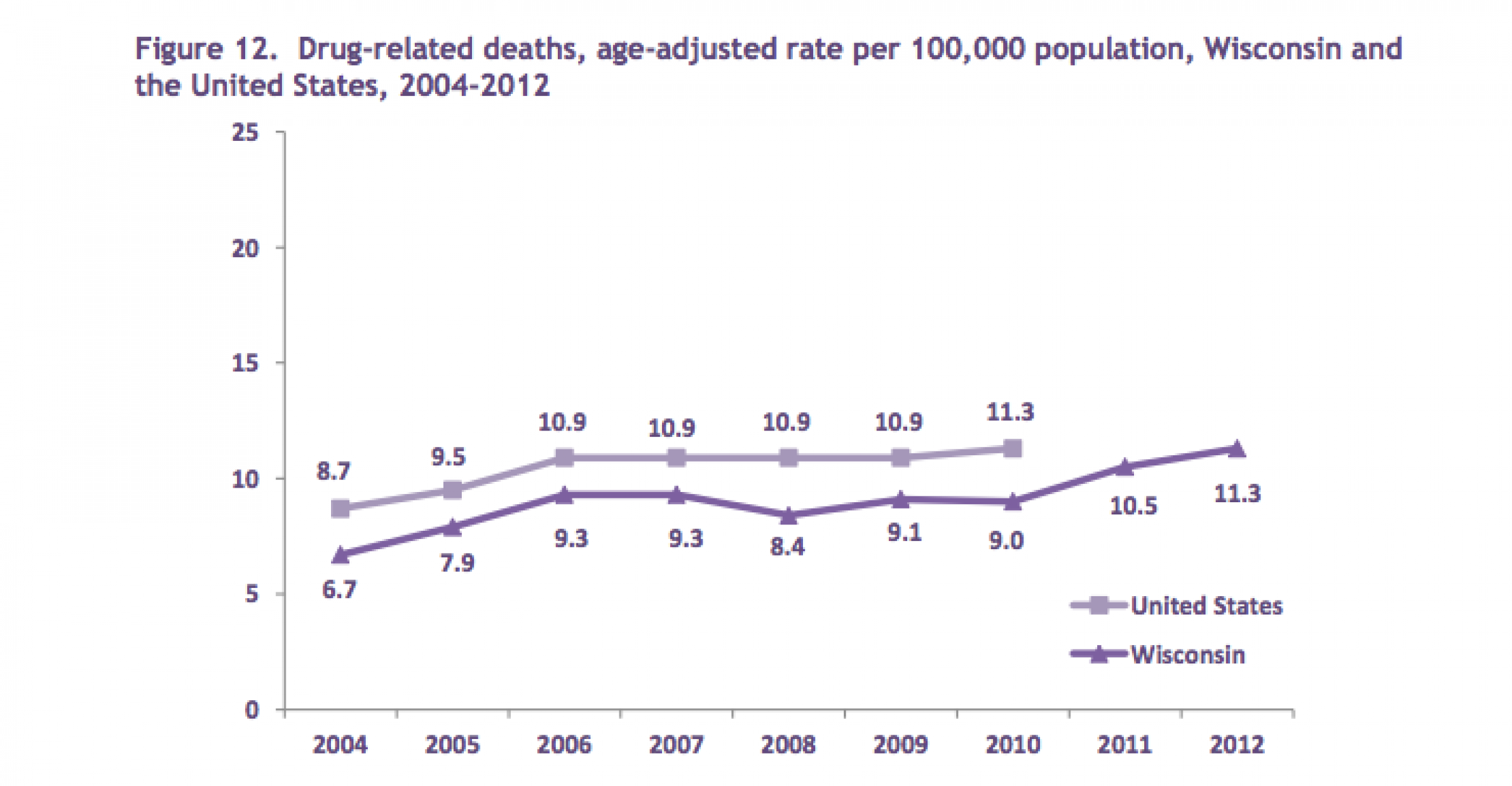

This problem certainly has been the case with the increasing abuse of prescription opioids, fentanyl and heroin in Wisconsin. In the past couple of years, state legislators and local officials across the state have acted swiftly to create policies aimed at preventing overdose deaths and helping people addicted to opioids get treatment. Yet both state and national data both clearly show that opioid-related deaths have been climbing for more than 10 years. Deaths from prescription opioids — fueled in part by doctors quick to prescribe painkillers — began to rise in the early 2000s, priming the pump for a subsequent rise in heroin overdose fatalities as addicts sought a cheaper option. It may all look staggeringly obvious in hindsight.

The lag that Cicero describes, though, makes those trends far less obvious when they’re first taking shape. It’s an issue that on some level touches anyone trying to understand substance-abuse problems on a deeper level. And this lag makes it harder to predict or catch new problems, and to craft responsive policy.

A closer look at Milwaukee

An entire research apparatus is in place to analyze information about drug abuse patterns — in academia, at federal agencies, and at state and local health departments. This work does not mean, however, that all local communities can count on having, say, an analysis of the demographics of who is dying of drug overdoses locally.

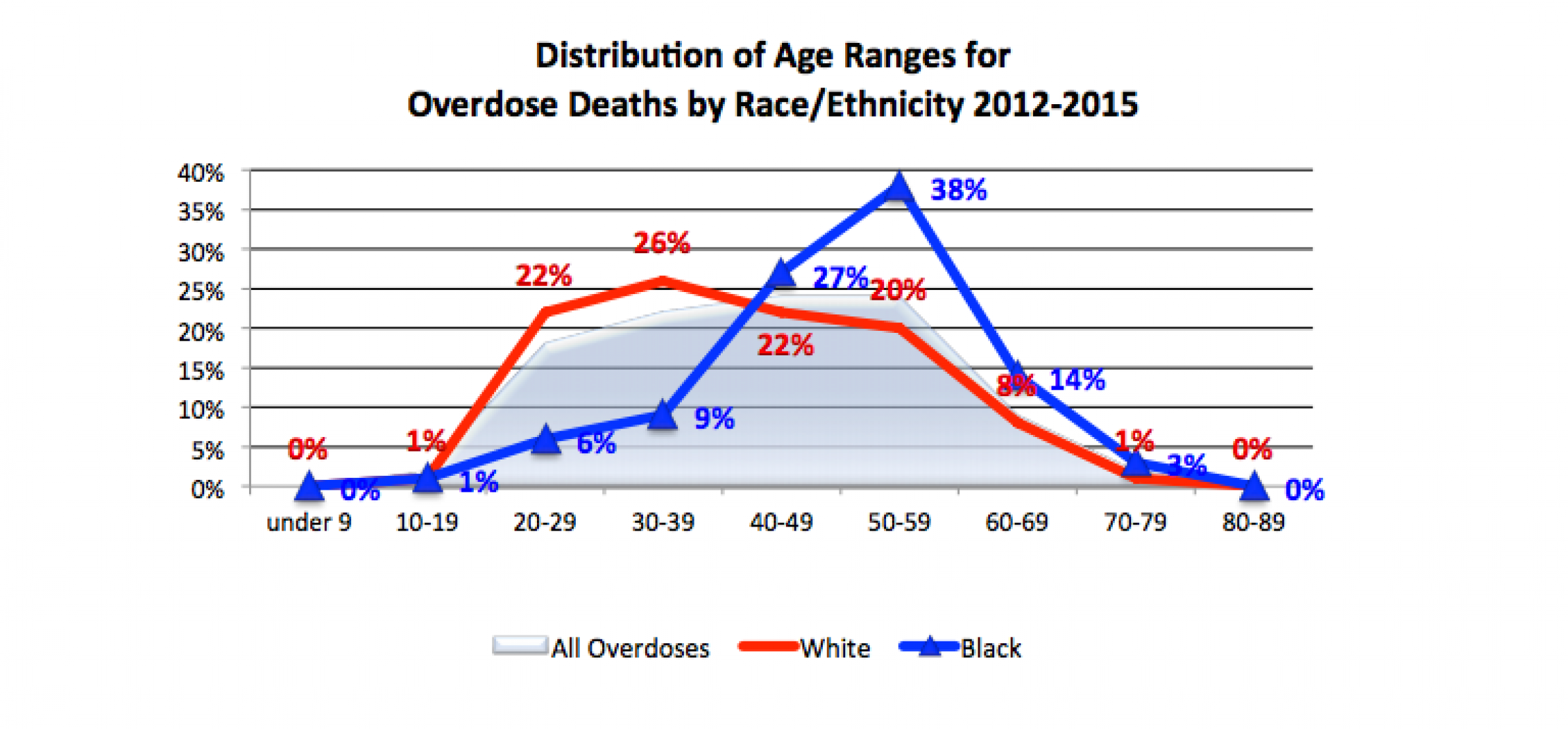

A relatively new report in Milwaukee about this issue, “888* Bodies And Counting,” and the ongoing research it kicked off, has opened an informative window into how opioid-related deaths afflict people in Milwaukee County, across different geographic areas, different age groups and different races. The raw data was there all along, thanks to the county medical examiner’s office, but a Milwaukee alderman had to leverage city funding, a grant from a local foundation, and help from the Medical College of Wisconsin to make the actual analysis happen.

And if someone points to another county in the state, especially a more rural one, seeking the same kind of granular analysis?

“It’s just not there,” said Gisela Berger, head of the professional organization Recovery & Addiction Professionals of Wisconsin, a clinical supervisor at a privately owned and operated methadone clinic in Milwaukee and a visiting associate professor of psychology at Concordia University. State agencies like the Wisconsin Department of Health Services do issue analyses of substance abuse problems, including the biennial Wisconsin Epidemiological Profile on Alcohol and Other Drug Use. (The 2014 edition is the most recent analysis available.) That report has some county-level breakdowns of alcohol and substance abuse data in the state, but it tends to lag a couple of years behind, and generally is not very granular.

Analyses like this might include some statewide demographic data and county-by-county numbers, but local-level insights — like the 888 Bodies* report’s finding that African-American overdose victims in Milwaukee tend to be older than white ones — are tough to come by.

“It’s very aggregate data,” Berger said. “It’s useful for someone who’s writing a dissertation perhaps, useful for justifying federal grants, and that’s about it.”

Berger indicated that private clinic operators like her employer, Acadia Healthcare, gather a lot of data about their clients. This information isn’t publicly available, though, and won’t necessarily reflect how substance-abuse issues play out in a given community or in a state as a whole.

The necessity of substance-abuse data

Shortcomings in substance-abuse data and analysis are not, of course, exclusive to opioids.

“I know of data that we’ve been collecting in Wisconsin for close to 20 years on certain alcohol-related problems that have never been compiled,” said Julia Sherman, coordinator of the University of Wisconsin Law School’s Alcohol Policy Project. Sherman is interested in the opioid problem because she is studying how alcohol abuse could lead to future opioid abuse, and because simply mixing alcohol and opioids is immediately physically dangerous.

If policymakers want to make decisions based on data, they’ll usually want to see information from multiple sources, Sherman said, and a detailed look at a problem like opioid abuse is going to take time. As she describes this challenge, it’s worth conducting analyses on the local level, even in smaller communities that might not have a lot of money or staff to devote to such a study.

It may be obvious at this point that Wisconsin has a problem with opioids, but the specific nature of how it’s unfolding will vary from one place to another, including between urban and rural settings. That difference means prevention and treatment resources would need to be allocated to address more specific needs.

“It’s extremely important because otherwise you risk spending your resources on a problem you don’t have,” Sherman said.

She used her organization’s work addressing alcohol use as an example: “We can say that underage drinking is a problem statewide, but there were a myriad of solutions that had to be implemented to address the specific problem within [a given] community. That requires data.”

People working with substance abuse issues firsthand might, understandably, have less of an interest in statistics.

“For us the issue is self-evident by the number of individuals we interact with on a daily basis through our needle-exchange program,” said Dottie-Kay Bowersox, public health administrator for the city of Racine.

Bowersox keeps up with federal and state data about substance abuse along with information from local law enforcement — but she thinks it’s more important to talk about the root issues of addiction. While Bowersox sees the state’s new slate of opioid policies as positive, she said policymakers and society as a whole tend to fixate too much on one particular category of drugs at a time, and should spend more time asking why people become addicts in the first place.

“We think that individuals should be able to pull themselves up by their bootstraps and get over whatever they’re addicted to overnight,” Bowersox said. “The problem needs to be dealt with comprehensively, versus just for this moment and just for this drug.”

Sherman agrees that the on-the-ground experiences of people like Bowersox are important, but don’t obviate the need for more analysis.

“You cannot eliminate human interaction from a human problem,” Sherman says. “On the other hand, when people talk one-on-one, there’s no guarantee that the experiences that they deal with extrapolate to the population as a whole.”

Improvements on the horizon

Empirical data is also a necessity for organizations that rely on federal funding. In 2015 alone, one federal agency, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, awarded 39 grants to government and private institutions in Wisconsin to combat substance abuse. The grants included $125,000 to support the efforts by the Manitowoc-based Northeastern Wisconsin Area Health Education Center to reduce substance abuse among young people. Annie Short, who administrates that program for the center, said determining data to learn whether this work has an impact can take a lot of legwork. She also points out that if communities had better data on substance abuse, they could make a stronger case for seeking additional state and federal funding, both for drug treatment and law enforcement.

“In a lot of communities, for us to get all this drug and alcohol data, we’re literally calling all of our ERs, all of our police, that kind of stuff,” she said.

Short credits police and hospitals with being helpful in her research, but has often encountered a lack of standardization. Not all law enforcement organizations use the same software or metrics to track drug-related arrests, and some medical examiners might list an overdose death as a suicide or even “natural causes” if they’re uncertain about the role of drugs or alcohol in a particular death. Lately, though, she has seen police take the initiative to be more consistent and in sync with each other with their software and tracking methods, and medical examiners becoming more diligent about conducting toxicology tests through a state lab.

Short said it would also help to have more specific information about drug arrests. She’s particularly interested in how many people charged with OWIs had other drugs in their system in addition to alcohol. But often, if a suspect has been drinking, the arrest record won’t include information about whether or not they were also using marijuana or prescription drugs.

Additionally, Should would like to see law enforcement enumerate drug-possession arrest records by type of drug.

“In most cases there is not that break-down,” she said. “Anecdotally they can tell you, ‘yes, we’re seeing more marijuana or more prescription drugs’ or whatever, but in terms of that data, it’s not broken down that specifically.”

And despite the efforts Short is seeing from the law enforcement officers she works with, she said it would be a tall order to get all of the agencies in the state on the same page when it comes to collecting standardized data.

“The state would literally have to pay for the system software and then mandate it,” she said.

Another source of information that helps Short in her work is that every public high school in Manitowoc County participates in the Wisconsin Youth Risk Behavior Survey, which asks students about drug and alcohol use, as well as other behaviors that could harm their health later in life. But in a lot of communities, she noted, not all schools participate in the survey, and in some communities none do. The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction issues a report on the survey every two years, but skipped 2015, because it wasn’t able to gather enough data.

There are ways for public-health researchers to try and anticipate new trends in substance abuse.

For about 10 years, Cicero, from Washington University, has been surveying patients in drug treatment centers around the country, asking them to share information about what they’re seeing among other users. The survey lets respondents check off certain drugs and combinations of drugs, but also answer some open-ended questions about drugs that might not already be on the researchers’ radar.

However, Cicero explained, lately the results of this method say more about the evolution of the opioid problem than about whatever might follow it. The proactive surveys were especially valuable as they tipped him off to the emergence of fentanyl.

“We can’t really predict what’s going to be next,” Cicero said. “It’s taken some strange twists and turns.”

Sherman, of the Wisconsin Alcohol Policy Project, said the health care, law enforcement and education communities need to talk to each other more. She sees that happening more often in Wisconsin, in part because federal grant programs like the Drug-Free Communities Support Program require recipients to bring those different sectors to the table. That kind of multi-disciplinary cooperation can make the cumbersome and expensive work of analyzing substance abuse a bit less daunting.

“It takes less legwork than you might suspect if you get the right people together,” Sherman said.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us