Not All 'Waters Of The State' Are Alike In Wisconsin Law

Efforts to have science inform law have played out vividly over the past 20 years of disputes over high-capacity groundwater wells in Wisconsin.

October 25, 2017

Shallows of Pleasant Lake in Waushara County

Science and law can both be slow-moving, deliberative fields, assembling bodies of theory and precedent that are subject to continuous yet glacial revisions through processes that seem arcane to outsiders, and bound up in conflict among warring schools of thought. When they converge, it’s rarely neat and tidy.

Efforts to have science inform law have played out vividly over the past 20 years of disputes over high-capacity groundwater wells in Wisconsin, and how they impact nearby surface water bodies like lakes, rivers and streams. Farmers, factories and even some local governments want to be able to drill and use high-capacity wells, which the state Department of Natural Resources defines as wells that can draw more than 100,000 gallons of water per day. But how exactly these wells are regulated at the local and state levels is a matter of serious legal contention.

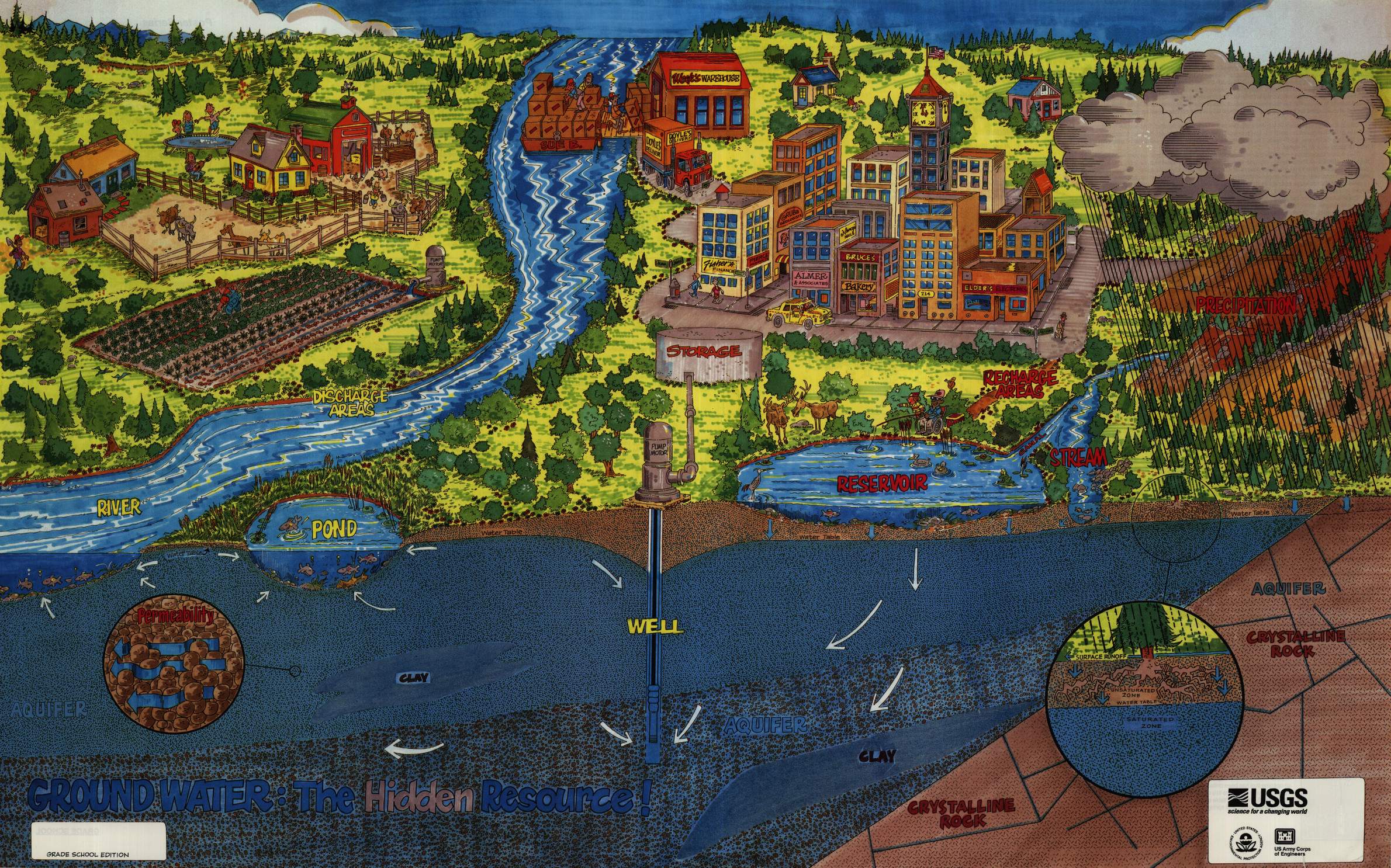

As plentiful and renewable groundwater is in Wisconsin, it can be used aggressively enough that the effects radiate far beyond the well itself. High-capacity wells can deplete the water available to other groundwater wells nearby, and because groundwater and surface waters are connected, they can likewise deplete nearby lakes and rivers.

Lawsuits, regulations and state statutes

The nature of interchange between surface water and groundwater is pivotal in two Wisconsin lawsuits, with one decided by the Wisconsin Supreme Court and the other still working its way through the court system.

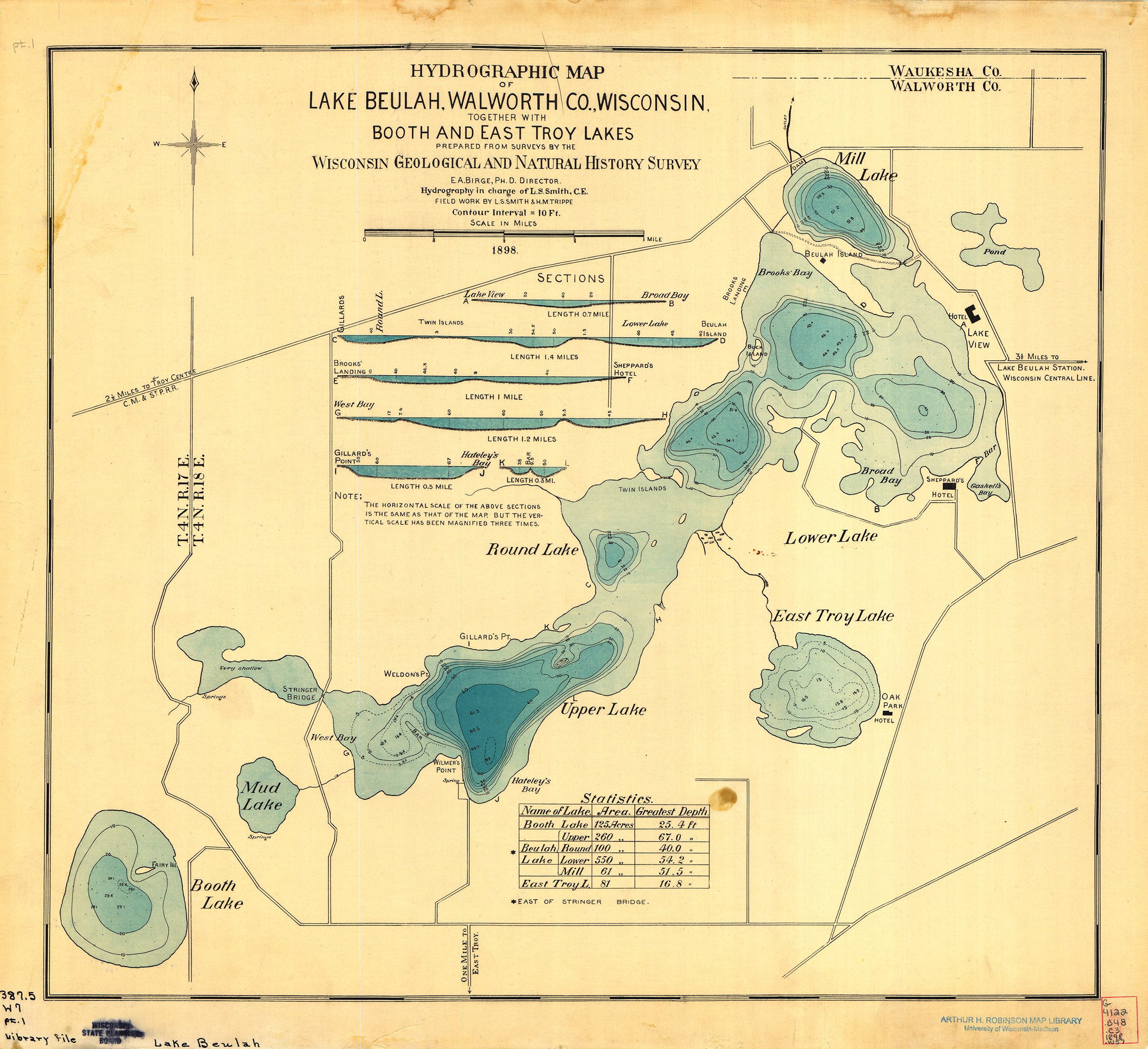

In the 2011 case of Lake Beulah Management District v. The Village of East Troy, the state Supreme Court unanimously ruled the “DNR has the authority and a general duty to consider whether a proposed high capacity well may harm waters of the state.” In that case, a dispute over a municipal high-capacity well and its potential effects on a lake in Walworth County, the court upheld the DNR’s decision to grant a permit for the well, holding the agency “was not presented with sufficient concrete, scientific evidence of potential harm to waters of the state.”

A more recent development in this area of Wisconsin law is in Clean Wisconsin and Pleasant Lake Management District v. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. In October 2017, a Dane County circuit court judge voided seven high-capacity well permits the DNR had granted and remanded one permit back to the agency for reconsideration. In her ruling, Judge Valerie Bailey-Rihn said the DNR failed to meet its obligations under the Wisconsin Constitution, because it issued the permits despite agency scientists concluding that the proposed well in question would harm nearby surface waters.

The state has not yet announced whether it will appeal in the case. A spokesperson for the Wisconsin Department of Justice said that officials there are still evaluating what to do next, but they did not respond to a request for further comment on the legal issues at issue in the case.

Carl Sinderbrand, lead attorney for plaintiff Clean Wisconsin, said in an Oct. 13, 2017 interview with Wisconsin Public Television’s Here & Now that if the case goes on to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, he anticipates a victory.

“I wouldn’t assume that our Supreme Court is going to take a partisan bent on this issue,” he said, noting that the legal issues in the case revolve around the state constitution.

In between those two rulings, Gov. Scott Walker and the Republican majorities in the Wisconsin legislature have taken multiple steps to weaken the DNR’s regulatory powers since 2011, including regulations pertaining to high-capacity wells. In May 2016, state Attorney General Brad Schimel issued an opinion asserting that DNR did not have authority to consider broader environmental impacts when issuing high-capacity well impacts; rather, he indicated that the agency should only consider factors specifically laid out in state statute. Acting on Schimel’s decision, the DNR quickly issued dozens of backlogged well permits.

There have been numerous other challenges in recent years to DNR’s authority to regulate groundwater, including a lawsuit the Dairy Business Association filed against the state in August over regulations on large farms called CAFOsand the passage of 2011 Act 21, which tightens the Legislature and governor’s ability to check regulatory agencies.

This amounts to a complex legal future for people who want tougher groundwater protections, despite their recent victories in court.

“We’re addressing these issues in a piecemeal fashion and that makes it awfully hard to get the big picture,” said Kara O’Connor, a lobbyist with the Wisconsin Farmers Union, which favors stricter permitting and monitoring of high-capacity wells.

Evan Feinauer, a staff attorney with Clean Wisconsin, finds the differing legal threads at play in Wisconsin water policy both compelling and troubling.

“As a lawyer I really like it because it implicates the constitutional and statutory and case law and its sort of a fun law-in-action approach to these problems, but it’s not academic,” Feinauer said. “The stakes are pretty high.”

Connected waters

The legal and regulatory question at the heart of these disputes is how much state regulators should weigh the impact of groundwater changes on surface water levels. On a scientific level, this relationship is well-understood: The hydrologic cycle illustrates how water flows from groundwater reserves into surface water bodies and vice versa.

One might assume that science-based policies would best address groundwater and surface water in concert, but this confluence doesn’t quite happen in Wisconsin law.

“We are a long way from an integrated kind of water policy in the state,” said Paul Kent, a Madison-based attorney who has represented clients in many important water cases and wrote the book Wisconsin Water Law In The 21st Century. “You kind of end up pounding square pegs into round holes a lot.”

Under state law, groundwater and surface waters are both considered “waters of the state” — which is a defined and pivotal legal term in Wisconsin (and elsewhere). However, the state’s authority to regulate groundwater use and surface water use derives from separate parts of the law. There’s also the matter of the word “navigable.”

Enshrined in article IXof the state constitution is a passage the legal and environmental community sums up as the “public trust doctrine”:

“The state shall have concurrent jurisdiction on all rivers and lakes bordering on this state so far as such rivers or lakes shall form a common boundary to the state and any other state or territory now or hereafter to be formed, and bounded by the same; and the river Mississippi and the navigable waters leading into the Mississippi and St. Lawrence, and the carrying places between the same, shall be common highways and forever free, as well to the inhabitants of the state as to the citizens of the United States, without any tax, impost or duty therefor.”

What this language means, or has been broadly interpreted to mean, is that navigable bodies of water in Wisconsin belong to everyone, and anyone can use those waters as long as they don’t interfere with others’ right to use them. If anybody oversteps those bounds through excessive use or pollution or, the state has the authority, and indeed an obligation, to step in and regulate that use.

“Navigable” encompasses just about any body of water one could paddle a kayak through, even potentially small streams that are dry part of the year. No reasonable person could argue that groundwater is navigable. But if a well causes a nearby lake or river’s water levels to drop, then it has been legally considered to have interfered with a navigable water. For environmental advocates seeking to limit high-capacity well use, that’s a compelling reason to establish a legal approach that parallels the hydrologic cycle. Indeed, this relationship between groundwater and surface waters is why judges ruled the way they did in both the Beulah Lake Management District and Clean Wisconsin cases.

The state also has direct authority to regulate the use of groundwater under what lawyers call its “police powers” — a state’s broader rights, created in the Tenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, to make its own laws. It was within this legal framework that the legal concept of “waters of the state” was born.

A state law enacted in 1919 gave the Wisconsin Board of Health (a precursor to today’s state regulatory agencies) authorities that included “general supervision and control over the waters of the state insofar as their sanitary and physical condition affects the public health or comfort, and it may make and enforce rules and regulations, and order the necessary changes or additions to correct and prevent pollution.” This law defined the “waters of the state” as including “those portions of Lake Michigan and Lake Superior bordering upon the state of Wisconsin, and all lakes, bays, rivers, streams, springs, ponds, wells and bodies of surface or ground water, whether natural or artificial within the boundaries of this state or subject to its jurisdiction.”

When it comes to the source of environmental authority in Wisconsin’s water laws, there’s no motivation to quibble over what’s considered navigable. But whereas the public trust doctrine spells out something the state must do, the police powers just note what it can do. This difference means someone who wants to compel the state to provide more oversight of high-capacity wells essentially has two options: One, convince a court to compel the DNR to toughen regulations under the public trust doctrine’s imperatives, or convince the state legislature to pass tougher legislation for the agency to pass, and then get the governor to sign it. Given that both the governor’s office and state legislature are controlled by regulation-averse Republicans, this approach has not been a likely avenue since 2011.

The distinction in law also reflects the different ways in which people commonly think about surface water and groundwater. A lake or river is something people can see, touch and interact with in a way that they don’t with groundwater. A lake or river is a pretty simple and obvious concept to most people, whereas groundwater is out-of-sight.

Even though groundwater and surface water are connected, there’s a general sense that groundwater is more pure and that surface water is more vulnerable to contamination. For instance, public water utilities that source surface water are subject to tougher federal regulations than those that use groundwater — surface-water utilities are required to disinfect their water, but in Wisconsin, groundwater utilities are not. These different rules make some sense — soil can be incredibly effective at filtering the contaminants out of water as it makes its way into the aquifers — but contemporary research has shown time and again that groundwater is very vulnerable to contamination from pathogens, nitrate and many other contaminants.

The future of the state’s waters

Other states and federal authorities have considered the connections between surface water and groundwater, said Steph Tai, a professor at the University of Wisconsin School of Law who sits on the board of environmental law firm Midwest Environmental Advocates, which filed an amicus brief in the 2017 high-capacity wells case.

“It’s not an unusual theory around the country,” she said.

But the fact remains that in Wisconsin’s statutes and regulations, there’s still a disconnect between how the two kinds of water are governed, and that won’t get fixed overnight, even with the imperatives that the public trust doctrine creates.

Attorney Paul Kent believes the public trust doctrine can only be pushed so far in compelling the state to set a more integrated water policy. He calls the problem a matter of legislative will. And court battles over high-capacity wells may not really move Wisconsin closer towards an approach that considers groundwater and surface water in concert.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us