Murder in Lac du Flambeau: An MMIP cold case gets renewed attention with DNA

The family of Suzy Poupart, a member of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa who was murdered in 1990, hopes advances in DNA testing technology can finally solve her murder after nearly 35 years and solve the case.

ICT News

April 9, 2025 • Northern Region

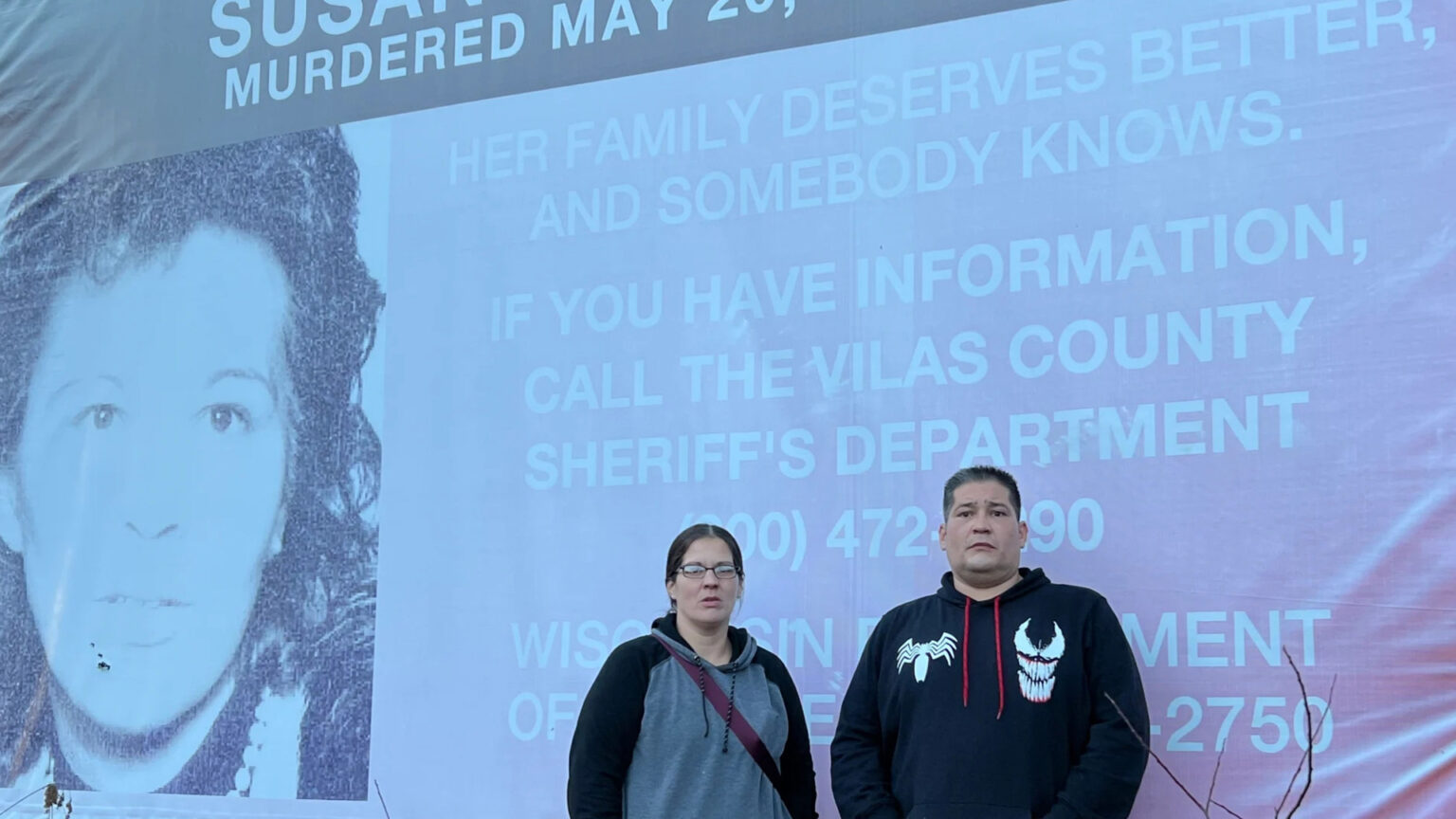

A faded billboard on the Lac du Flambeau reservation in Wisconsin asks for help in solving the murder of Susan "Suzy" Poupart, who went missing on May 20, 1990, and whose remains were found six months later. Her now-grown children, Alex and Jared Poupart, shown here in October 2024, are hoping that new DNA technology can finally solve the case. (Credit: Mary Annette Pember / ICT)

This story was originally published by ICT, formerly Indian Country Today.

LAC DU FLAMBEAU RESERVATION —The billboard glows ghostly white in the moonlight. But the outlines of Suzy Poupart’s face are still visible, gazing stubbornly out at the world, demanding justice for her 1990 murder, urging anyone with information to come forward.

Placed as it is on the main road between the reservation and the town of Minocqua in rural Wisconsin, the billboard is an unavoidable daily reminder that the plague of missing and murdered Indigenous people touches every corner of Indian Country, even here on the tiny Lac du Flambeau reservation.

But justice may be coming soon for Poupart and her family. Advances in DNA technology have prompted police to test evidence that was collected when her body was found several months after she disappeared in a remote cedar swamp surrounded by dense brush. The DNA could provide links to three local men who are widely considered suspects in her death — or clear their names.

This year, on May 20, will mark 35 years since Suzy went missing. Her children are adults with families of their own, living and working on the reservation. And two of the suspects, now in their mid-50s, also live and work in Lac du Flambeau. A third suspect is in prison on an unrelated charge.

The results from the DNA tests are imminent and may emerge sometime in 2025. Now, Suzy’s family, including her daughter Alexandria Poupart and son Jared Poupart, and members of the tribal community, are waiting for the other shoe to drop.

In the meantime, unavoidably, they face one another occasionally in the small, insular tribal community, with each — victims and suspects — forced to relive their guilt, grief or anger, over and over.

“I’ve been lied to my whole life, so to me the truth matters more than anything,” Jared, 44, a single father of one son, told ICT, as he sat in the living room of his home on the reservation along with his 38-year-old sister, Alexandria, called Alex by family and friends.

“They say the truth will set you free but around here all it does is start a fight.”

Chairman John D. Johnson Sr. of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians said the community will be relieved once the case is solved.

“It’s under active investigation,” Johnson told ICT. “People have been implicated but they’re innocent until proven guilty in a court of law.”

Code of silence

Elders say that Suzy’s murder hangs over Lac du Flambeau like a dark cloud, festering with hatred and anger, even as the suspects have gone on with their lives on the reservation.

“Suzy was a good friend who always helped me, especially when I was trying to exit a violent relationship,” said one woman, who did not want to be identified by name. “Like me, she had bad luck with men but she sure loved her kids.”

Suzy, who was 29 when she was killed, was an aspiring sculptor and artist who had studied at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe in the late 1980s. After learning she was pregnant, she traveled from Santa Fe with her boyfriend, Alex’s father, to his home state of New Hampshire. According to Jared, however, the boyfriend’s family was less than welcoming, clearly prejudiced against the young Ojibwe woman. After the boyfriend turned violent, Suzy returned to her childhood home, the Lac du Flambeau reservation, where her parents, siblings and other relatives lived.

By 1990, she had a house of her own on the reservation and was working as a waitress at the tribal casino and caring for her two children. Then she disappeared.

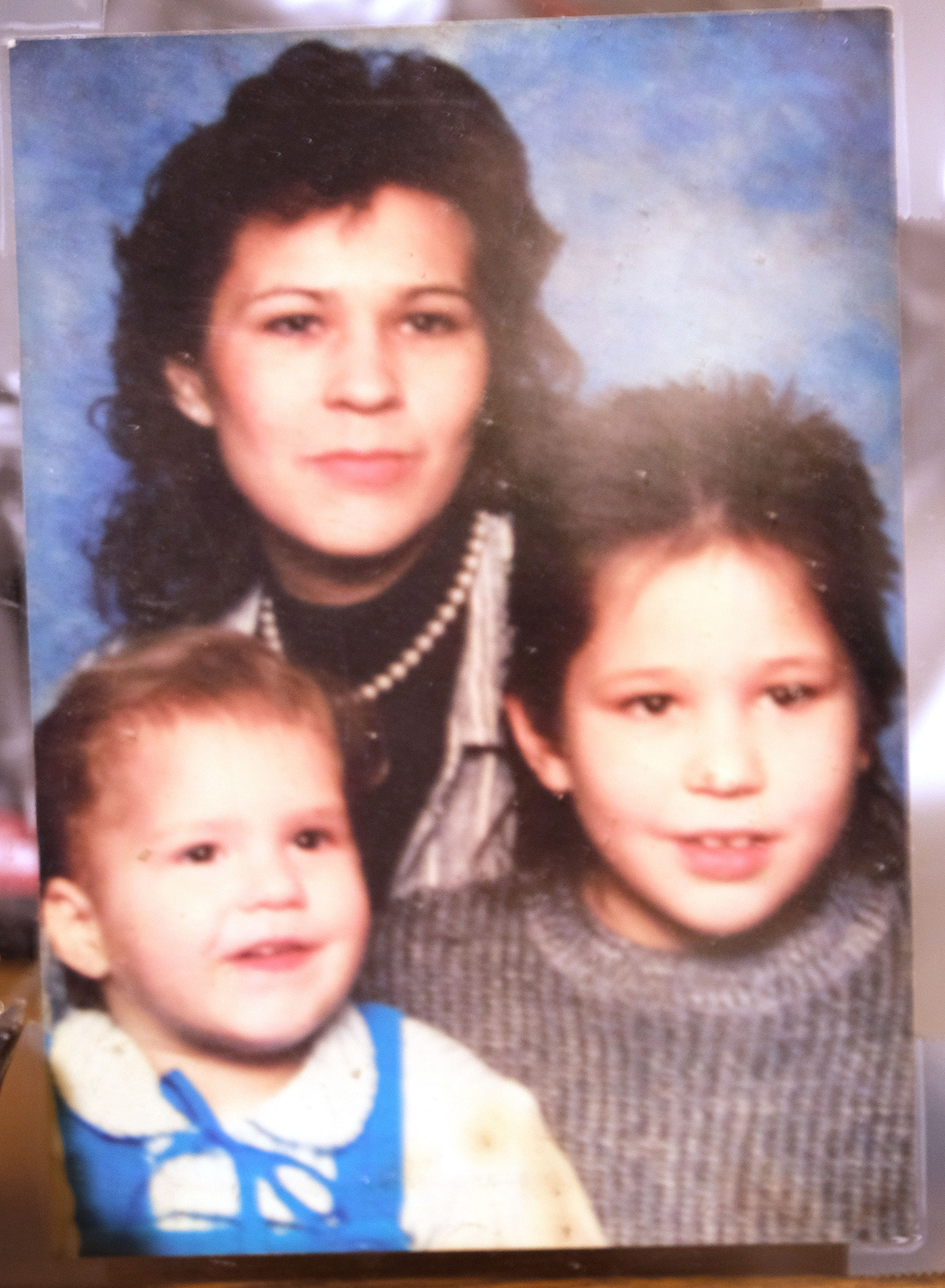

A family photo shows Susan “Suzy” Poupart with her children Alex, 3, and Jared, 9, in about 1990, shortly before she died after going missing on the Lac du Flambeau reservation in Wisconsin. (Credit: Courtesy of the Poupart family)

Historically, rates of murder, rape and violent crime among Native American and Alaska Native peoples are higher than the national averages, and the overall violent crime rate on reservations is about 2.5 times higher than the national average. The U.S. Department of Justice files charges on about half of the murder cases on Indian lands.

Like many of the cases of missing and murdered Indigenous people — particularly women — the investigation into her case fell dormant off and on over the years, despite efforts by the family and rounds of investigators, including Vilas County Sheriff Joseph Fath, to keep it open.

For Jared, the lack of attention to the case over the years reflects the justice system’s indifference to Native people. The impunity extended to the suspects creates a destructive, trickle-down effect for the whole community, he said.

“Our next generation of leaders soak up events like this, knowing you can do something horrible to a Native woman and get away with it,” Jared said. “Fath has worked on it, but I’ve got to wonder, if my mom was White, we wouldn’t be where we are today – it would’ve been solved by now.”

About 1,500 tribal members live on the checkerboard reservation that stretches out over 86,000 acres that also includes more than 50 percent non-Native residents. Chief Keeshemun settled his band of Ojibwe here in the 1700s, but Ojibwe people began migrating to the region more than 1,000 years ago from an area around the St. Lawrence seaway.

Among the six bands of federally recognized Ojibwe in Wisconsin, the Lac du Flambeau band is a small, close-knit community where people are bound together not only by a common culture but also generations of family ties. Informal beaten paths through the woods connect the little neighborhoods of split-level homes.

The tribe with its casino, modern health clinics, education and social services departments is currently the largest employer in Vilas County. Although much has changed on the reservation since the 1990s, traditional ways continue in Lac du Flambeau, where residents still rely, at least in part, on traditional hunting and fishing to feed their families. During a recent visit to the area, ICT spotted a wide swath of fresh blood dripping from the tailgate of a source’s truck. Although such a sight might be shocking in some communities, on the reservation it was the mark of a good provider who’d bagged a deer for his family.

Here, everyone knows everyone and memories run deep, as does an ingrained code of silence that Native people have adopted for survival for generations.

Two of the main suspects in Poupart’s murder now work and reside on the reservation, raising families and freely living their lives. A third is incarcerated with a conviction for impaired driving. Despite compelling circumstantial evidence and dogged police work tying them to Poupart’s death, the suspects, all citizens, like Suzy, of the Lac du Flambeau tribe, have been interrogated but not charged.

Suzy was last seen in the early morning hours of May 20, 1990, getting into a car with the three young men after leaving an after-hours reservation party.

According to witnesses, Suzy and the men had been drinking and appeared to be intoxicated. The three men were heard by witnesses telling Suzy they would drive her home, but people reported that the car turned the opposite direction, away from Suzy’s home as it left the party, according to police.

Some witnesses say that she was forced into the car, others say she went willingly. And some recall that the pretty, petite woman was too intoxicated to make such a decision, police said.

Suzy was a single mother of then-3-year-old Alex and 9-year-old Jared. She enjoyed going out with friends, who describe her as funny and fun to be with, a firecracker who took no guff from anyone, especially men.

“She always held her head high,” recalled a friend who, like others interviewed by ICT, asked for anonymity, fearful of retaliation by the murder suspects or their families.

Suzy was known as a good friend as well to many other Native women who spoke to ICT, as a person they turned to for support. Although they, too, are fearful to be identified publicly, they all want the world to know that Suzy was a good person who deserves justice.

Their secret outrage winds through the reservation, a flow that lifts up Suzy’s two children as best it can without putting other families at risk.

Suzy’s children were staying with her sister the night she went missing. But both her sister and her mother quickly grew worried when Suzy didn’t return in the days following May 20.

Although she was known to stay out late or even overnight, she always returned for her children.

“My grandma had a bad feeling and begged her not to go out that night,” Jared recalls. “Grandma never forgave herself for that, beating herself up for the rest of her life.”

The community, Suzy’s family and the sheriff organized searches over several days but found nothing.

Six months later, however, on Thanksgiving Day, deer hunters deep in the nearby Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest found Suzy’s remains, wrapped in plastic with duct tape and covered with debris.

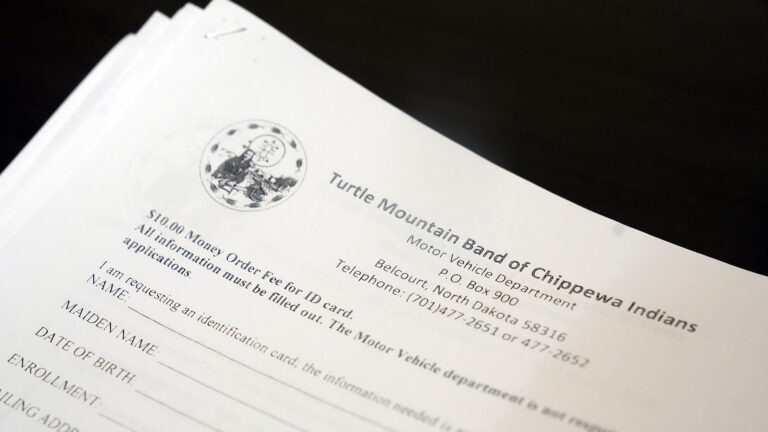

The hunters also found her jacket and tribal ID, and immediately connected the findings to the woman who been reported missing in May. The hunters reported their findings to the Vilas County Sheriff’s Department, which has authority over crimes on Indian reservations under Wisconsin Public Law 280.

Deer hunters in the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest in Wisconsin found the remains of Susan “Suzy” Poupart on Thanksgiving Day in 1990. The cedars in the area may have helped preserve DNA evidence, which is being tested in 2025 using new technology. (Credit: Mary Annette Pember / ICT)

Jared recalls an uncle telling him the news that day and the subsequent whirlwind of police questioning, so confusing and unsettling for a child.

“He told me my mom wasn’t coming home and I refused to believe him at first,” Jared said. “Later, police showed me her purse and a necklace they found with her, wanting me to identify them as hers, but I didn’t understand.”

Alex remembers nothing about that day and recalls little about her mother. “She went missing in May, two months after my third birthday,” Alex said.

Alex’s memories, she says, appear like dreams, or fleeting photographs flashing through her mind’s eye. In one, she recalls entering her mother’s room and seeing her lying in bed. Jared, however, has clearer memories, of going snaring for rabbits with Suzy and family, of an uncle teasing him after an oversized snowsuit Jared wore that prevented him from getting to his feet in the deep snow, and how everyone laughed.

A handful of blurry photos are all that remain now of the little family. In one photo, Suzy and the children are joined by cousins on a summer’s day, dressed in swimsuits, laughing as they crumpled to the ground, an affectionate tangle of arms and legs with Suzy’s arms wrapped around them.

New technology

The place where Suzy’s remains were found is known mostly to hunters, but her remains were so degraded that investigators had to confirm her identity through dental records using a partial jawbone.

Suzy’s skull was never found, and the coroner was unable to determine a specific cause of death, though her death was ruled a homicide. Her remains were severely decayed from months spent out in the elements and had been damaged by animals that left tooth marks on her bones.

“Her remains fit into one Ziplock bag; we buried her with that and a dress,” Jared said, noting he didn’t learn those facts, mercifully, until he was an adult.

But police extracted several samples from the evidence of DNA that did not belong to Suzy. The available technology in 1990 gave investigators only the most rudimentary information – that the DNA belonged to men. Remarkably, the evidence continues to be stored in police custody today, unlike evidence in many murder cases in Indian Country, especially cold cases, in which the evidence is mishandled due to lack of police resources.

The soil of the cedar swamp may have contributed to saving some of the evidence from decay, according to Detective Sgt. Cody Remick of the Vilas County Sheriff’s Office. Although Remick wasn’t aware, cedar plays important medicinal and spiritual roles in Ojibwe culture, especially for women.

Community members wonder, did the medicine play a role in protecting the evidence in Suzy’s murder?

But the Vilas County Sheriffs Office sent off three more promising pieces of evidence in February for analysis at three separate labs that use the latest in advanced technology that wasn’t available when Suzy was found in 1990.

Among the new techniques is something called Forensic-Grade Genome Sequencing, FGGS, to find DNA matches even from very small, incomplete samples.

The technique is used by a Houston company, Othram, which received a $1 million contract from the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Missing and Murdered Unit in 2022 as part of the agency’s Operation Spirit Return, an initiative to help solve missing and murdered cases involving Native Americans and Alaska Natives. In January, Othram, as part of Operation Spirit Return, successfully identified the remains of Michelle Elbow Shields of the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota who was reported missing in 2023.

“FGGS allows us to create a highly detailed DNA profile even from old, degraded or tiny evidence,” David Mittleman, CEO of Othram, told ICT.

The Vilas County Sheriff’s Office isn’t using Othram to conduct the latest tests, but has submitted evidence to private, state-run and FBI labs, according to Remick. The tests also include genetic genealogy sequencing and are expected to be completed sometime in 2025.

A Thanksgiving gathering

Jared invited ICT to his home in 2024 to celebrate Thanksgiving and to talk about his mother and his life since she was murdered.

“To me, Thanksgiving is a reminder of when they found my mother so that day and the whole holiday season into Christmas has always been mixed with pain and sadness,” Jared said.

But that was nearly 35 years ago and now his young son, age 11, is excited about the holiday. A cousin joined the small gathering for dinner. Jared, a single dad devoted to his son, cooked up a feast of turkey and all the fixings in his little kitchen. Rich pies, chocolate and pumpkin, prepared by a neighbor, completed the meal.

The children’s lives were never the same after her death. They were raised separately by various family members and friends. In some cases, caregivers did their best; in others the children later learned that their resources had been misappropriated by the adults charged with their care. For a time, they lived in foster care and at times were homeless.

Although their most basic needs were usually met, their childhood was permeated by a skinny kind of love, meted out by obligation rather than motherly affection. And worse, they found themselves scapegoated by some members of the community.

“Rather than accept accountability, they’ve put the shame and blame on us; that’s how wild it is here,” Jared said.

Jared said he was angry in the years after his mother died. He was outraged seeing the suspects walking around freely, raising families and living their lives. He said he and Alex have been the targets of outbursts by the men’s families.

“One of those dude’s daughters used to holler at me, ‘Hey, my dad didn’t kill your mom,'” Jared told ICT. He turned to alcohol for a time.

“Every time I saw those guys I would flip out,” he said. “I used to drink, party and fight when I was young.”

But he soon realized that his mother wouldn’t have wanted him to waste his life awash in self-destruction.

Today, Jared works at a tribal economic support program that helps people in need. He also serves on the tribal council and is busy raising his son.

“I’m trying to offer him a better life than what I’ve gotten,” Jared said.

Alex said her brother is well thought of on the reservation. “He’s seen as a fair man who pushes for everyone to get equal treatment,” she said.

Sometimes, Jared said he feels like giving up, but he keeps moving forward.

“That’s not who I want to be remembered as, you know? The guy who’s ma got murdered and he went off and just beat people up and drank his whole life,” he said. “I’d rather be remembered for helping people.”

Susan “Suzy” Poupart holds her daughter Alex in this undated photo. Poupart went missing on May 20, 1990, on the Lac du Flambeau reservation and her remains were found six months later. The family is now hoping that new DNA technology could finally solve the case. (Credit: Courtesy of the Poupart family)

Alex said she was also angry as a child, but today is a stay-at-home mom who dotes on her five boys; most of her time is spent caring for them. She and her family live near the house where her mother was last seen at the party.

During a previous visit with ICT at her home, the boys tumble playfully over her bed as she pulls out one of her mother’s ceramic pieces created when Suzy attended the Institute of American Indian Arts. Alex keeps the vase, shaped like a Native man wearing a headdress, wrapped in a colorful, handmade afghan.

Holding the vase tenderly, she describes the challenge of wanting to protect her children but also telling them the truth. The boys, for example, saw the face on the billboard and thought it was their mother, and not their grandmother. They asked her about it.

“Folks around here say I look just like my mother,” she said proudly. “I finally had to break down and explain that their grandma was murdered.”

Although she didn’t go into detail about the crime, she hopes for the day when it is solved.

“When it all comes out, I can explain everything to them and how we are now getting justice,” she said.

Alex and Jared wonder what their lives would have been like if Suzy were alive today. Although it’s too raw even now to think about, Jared sometimes recalls how Suzy carefully laid out his school clothes every night before bed.

“They took away our whole life with her,” Jared said.

When Alex and Jared turned to traditional Ojibwe spirituality for healing and solace they found those spaces occupied by some of the suspects in their mother’s murder.

“We have to travel far away from home if we want ceremony,” Alex said.

‘People are afraid of these men’

All three of the men identified as suspects in the case have been arrested several times on charges of violence against women, and each has spent time in jail for various crimes related to drugs and assault, according to Fath, who was one of the original investigators on the case in 1990 and is now the Vilas County sheriff.

It was among the first murder cases of his career and one that continues to haunt him. Fath’s great hope is to solve Suzy’s murder before he retires.

All three suspects left the area shortly after Suzy’s remains were found, Fath said. One man enlisted in the military, and the other two also left for undisclosed locations for a number of years. Eventually, however, they all circled back home to Lac du Flambeau.

Fath said the suspects have been protected by fear of retaliation by their families and relatives, as well as a well-founded generational fear among Native people of the mainstream government.

“I think a lot of people just don’t want to be labeled a snitch; they just want to mind their own business,” Fath said. “And people are afraid of these men.”

Mistrust of law enforcement in Indian Country has deep, legitimate roots that has carried over into current generations, according to Walt Lamar of the Blackfeet Nation of Montana. Now retired, Lamar worked with the FBI as a special agent and also served as deputy director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs Office of Law Enforcement.

“Law enforcement in Indian Country started out as military rule and was actively distrusted and disliked,” Lamar told ICT.

Indeed, according to research by the National Institute of Health, discrimination and harassment against Native Americans in U.S. institutions are systemic and untreated. And according to the Minnesota Journal of Law and Inequality, Native peoples are among the most common victims of police violence.

But fear of retribution from within small communities is not unique to Indian Country. Research from the Rural Health Information Hub found that, in general, people living in rural areas where perpetrators may be closely aligned with law enforcement and others in leadership roles are reluctant to report information to the police.

Fath said people are afraid to talk openly with police, but many have come forward privately.

“We’ve talked to hundreds of people in Lac du Flambeau since Suzy was murdered and have run down hundreds of leads,” Fath said.

But the investigation has proceeded, sometimes sporadically, over the years. Occasional public interest, often fueled by the media, continues to keep Suzy’s case from fading away. And the Vilas County Sheriff’s Office continues to invest time and effort into working the case.

Not long after Suzy’s death, Fath traveled to Florida, where one of the suspects was in training at bootcamp. Fath interviewed the man over several days. The suspect asked him at least twice to remove a picture of Suzy, saying he disliked her eyes staring at him.

“I had a picture of Suzy that I kept on the table the whole time,” Fath recalled. “I said, ‘No, the picture stays here; you need to see her.'”

But the man insisted he was not involved with Suzy’s death.

During initial interviews with police, all three men admitted that they offered Suzy a ride home from the after-hours party in May 1990. According to them, however, they had a disagreement with Suzy after she got into the car so they let her off near the tribal school where the tribe’s casino, Lake of the Torches, is located today.

“All of them have spent time in our jail over the years for other charges,” Fath said. Each time, Fath offers to talk with them about Suzy’s murder, but they decline.

“One of their relatives has gotten extremely angry with our department over our questioning but, as I’ve told her, that since they are the last people who saw Suzy alive they represent important sources in the crime,” Fath said.

Vilas County Sheriff Joe Fath, left, and Detective Sgt. Cody Remick, shown here in October 2024 at the sheriff’s office in Eagle River in northern Wisconsin, both investigated the 1990 murder of Susan “Suzy” Poupart in Lac Du Flambeau. (Credit: Mary Annette Pember / ICT)

As the Poupart case began to grow cold, Fath had a revelation about several strands of deer hair that were present on Suzy’s remains, recalling that investigators had also retrieved samples of deer hair from the car of one of the suspects. Fath sent both samples to a laboratory in Alabama, but in another maddening string of obstacles in the investigation, a hurricane swept through the area, destroying the deer hair and the laboratory before any results were obtained.

At one point, investigators even consulted a psychic in the case. “We didn’t want to leave any stone unturned,” Fath said. The psychic, however, failed to uncover any useful information.

In the 1990s and again in 2007, investigators held a series of so-called “John Doe hearings” to look into Suzy’s murder. In Wisconsin, a John Doe hearing is convened by a judge in order to determine whether a crime has been committed within the court’s jurisdiction. According to Wisconsin statutes, “a judge shall convene a proceeding and shall subpoena and examine any witnesses the district attorney identifies.”

All three suspects and a family member were among those subpoenaed to appear before the court. One suspect appeared before the court but declined to answer questions and invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. At least one regional television news station attended the 2007 hearing and publicly reported the suspects’ names. Subsequently, a number of media outlets have also named the suspects.

ICT, however, is not naming them, since the case is still open and transcripts of the John Doe hearing have been sealed. ICT reached out to each of the suspects via social media and telephone as well as through the Wisconsin Department of Correction. All declined to comment.

In the late 1990s, the Vilas County Sheriff’s Office erected the billboard featuring Suzy’s face to encourage the public to report information about her murder. The billboard was vandalized and destroyed by fire shortly afterwards, but authorities replaced it.

“We decided to put up the billboard so people wouldn’t forget about Suzy,” Fath said. “Those guys had to look at her face every time they came to town from the reservation. We figured someone involved with the murder destroyed the first one.”

The investigation, once again, however, fell largely dormant.

A fresh start

In 2018, Remick, now the detective sergeant, joined the sheriff’s department as an investigator and brought fresh eyes to the case.

He learned about the new DNA techniques during a police training and began pursuing advanced testing in Suzy’s case, but funding was scarce. The cost of advanced DNA testing can reach as high as $30,000, far exceeding the annual forensics budget of a small police force, according to Fath and Remick. Public Law 280 is an unfunded mandate so law enforcement charged with policing reservation communities aren’t compensated by public funds.

Fortunately, however, the burgeoning popularity of true crime and cold-case podcasts, television shows and documentaries helped drive public interest in solving these cases. The weekly true crime podcast, “Crime Junkie,” created by Ashley Flowers and Brit Prawat, began including stories about missing and murdered Indigenous peoples, and in 2021 mentioned Suzy’s case.

Remick learned that Flowers and Prawat also created a foundation, Season of Justice, that funds cold-case investigations, and he secured a grant to conduct additional DNA testing on evidence found in the case.

With funding from Season of Justice, the Vilas County Sheriff’s Office sent evidence to a state crime lab in August 2024 for additional DNA testing. The lab uses a new vacuuming method that can extract even minute bits of DNA.

Susan “Suzy” Poupart, a citizen of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa in Wisconsin, went missing May 20, 1990, and her remains were found six months later. Her family is hoping that new DNA technology can help solve her case in 2025. (Credit: Mary Annette Pember / ICT)

Suddenly, the stars aligned for the Poupart family, once again pushing the case onward. Around the same time, Alex organized a crowdfunding campaign to pay for additional DNA testing. The fund is currently just over $10,000.

In the summer of 2024, Ron Carlson, a retired architect from Chicago who frequently vacations in the area, took an interest in Suzy’s case. Carlson is an adventurer of sorts who flies his private plane to remote areas in Alaska and Canada.

During retirement he gained an interest in cemeteries and the stories behind those buried there. He created a YouTube show called, “Faces of the Forgotten,” in which he shared his findings. Carlson receives no funding for the show, which now has more than 700,000 followers.

“It just took off,” he said in an interview with ICT.

According to the show’s online description, it “recognizes people who have passed on long ago and are, as of today, mostly forgotten. It also features some graves and tombs of famous and infamous people and associated events.”

Carlson became intrigued by Suzy’s case and tracked down Alex and Jacob. He featured the story on “Faces of the Forgotten,” and announced at the same time he was donating $10,000 to pay for additional DNA testing.

“I watched that billboard fade away almost to white over the years,” Carlson said.

Once again, Suzy’s story gained public attention. Several media outlets revisited the case and described Carlson’s role in it.

“Ron’s interest in the case was like perfect timing along with a new detective on the case,” Jared said.

Although pathologists who first examined Suzy’s remains were unable to uncover a definite cause of death, Jared and Alex have put together what they think is a likely progression of events that took place the night Suzy was murdered. Several people have shared third-hand information overheard from the men over the years.

According to the repeated stories, they believe Suzy got into the men’s car then resisted sexual overtures. They believe she was sexually assaulted and then killed before being taken to the national forest. Police agree that is likely the chain of events. They also believe that at least one additional person helped cover up and destroy evidence.

“We’ve always heard that it was her beauty that got our mom killed,” Jared said. “Since she wouldn’t be with them willingly, they had to kill her.”

Looking ahead

Jared believes that greater attention on missing and murdered Indigenous people will lead to more justice in Indian Country.

In March 2025, Suzy’s billboard was replaced with a fresh one with funds raised in June 2024 by the Wisconsin Indigenous Riders, which held its 4th annual motorcycle ride to raise awareness about missing and murdered Indigenous people and opioid use.

In late February, “Crime Junkies” featured Suzy’s case on another of its broadcasts, “The Deck,” which refers to decks of playing cards created by the Department of Justice depicting unsolved crimes. The decks of cards are routinely distributed to jails and prisons in hopes someone will recognize a case and come forward with information. Suzy is featured on the seven of clubs.

Flowers also hosts “The Deck,” which revealed on a recent show that the initial round of DNA testing failed to produce enough evidence to create a profile. Remick confirmed those details.

The good news, however, is that additional funding from the Poupart family’s crowdfunding effort and Carlson’s donation will help pay for testing of three other samples of DNA gathered at the scene, according to Remick.

Police and Suzy’s family have been down this road many times before, however, so they are not getting their hopes up.

“I try not to think about it too much, I focus on other things in my life like my kids and family,” Alex said.

Alex Poupart shows her son one of the art creations by her mother, Susan “Suzy” Poupart, in October 2024. Alex and her brother, Jared Poupart, are now hoping new DNA technology can finally identify the men who killed her in 1990. (Credit: Mary Annette Pember / ICT)

Although the circumstantial evidence against the men is compelling, Fath said that the best chance for successful convictions is hard, physical evidence. “So far, they know if they keep their mouths shut, we aren’t likely to convict them,” Fath said.

Remick said they are not giving up on the investigation.

“We want everybody to know that this is not going away,” Remick said. “This is something we’re still working on.”

Jared and Alex hope that one day soon the sheriff will call to tell them charges are being pressed against the men. “That would open the door for some closure for my and my sister’s lives,” Jared said.

Jared and Alex aren’t alone in their vigil. Many of Suzy’s old friends are quietly supporting them.

“I often drive by the place where they found her,” another friend told ICT.

Gazing out at the forest’s curtain of dense pine, the friend paused, breathing out softly.

“I think of her, of Suzy, every time I drive by here on my way home.”

ICT, formerly Indian Country Today, is a nonprofit news organization that covers the Indigenous world with a daily digital platform and news broadcast with international viewership. Sign up here for ICT’s free newsletter.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us