Milwaukee elections worker fired over false ballot requests

Mayor Cavalier Johnson said Kimberly Zapata, the deputy director of the Milwaukee Election Commission, requested three fictitious military ballots from clerks in nearby municipalities.

Associated Press

November 3, 2022

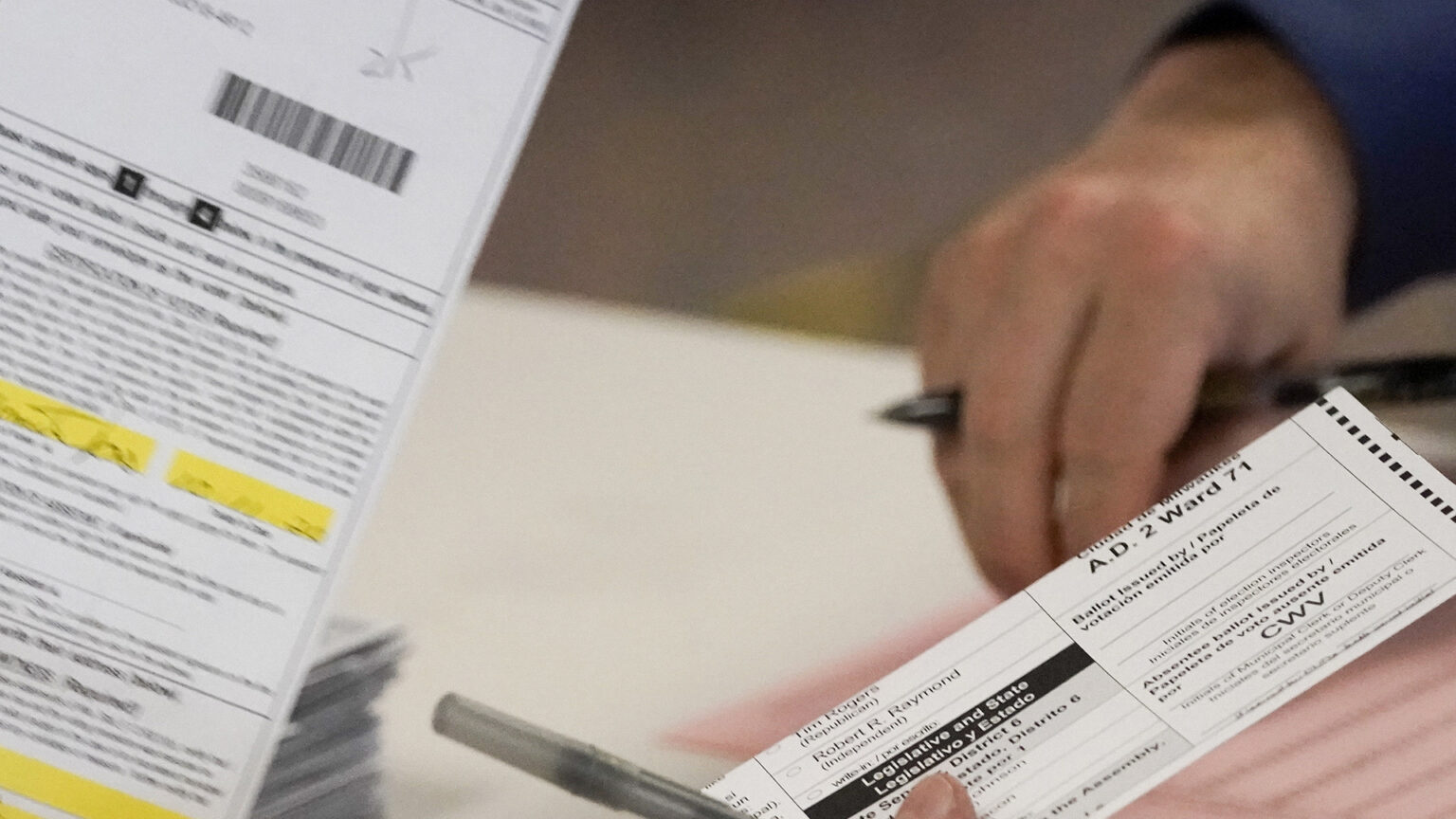

Workers count Milwaukee County ballots on Election Day at a central count location on Nov. 3, 2020, in Milwaukee. A top Milwaukee elections official has been fired after sending falsely obtained military absentee ballots to the home of a Republican state lawmaker who has been an outspoken critic of how the 2020 election was administered, the city's mayor said Nov. 3, 2022. (Credit: AP Photo / Morry Gash File)

MADISON, Wis. (AP) — A top Milwaukee elections official has been fired after sending falsely obtained military absentee ballots to the home of a Republican state lawmaker who has been an outspoken critic of how the 2020 election was administered, the city’s mayor said Nov. 2.

Kimberly Zapata, deputy director of the Milwaukee Election Commission, requested military ballots for fictitious voters from clerks in nearby municipalities using the state’s MyVote Wisconsin website, Milwaukee Mayor Cavalier Johnson said just days before the midterm elections.

“This has every appearance of being an egregious, blatant violation of trust, and this matter is now in the hands of law enforcement,” said Johnson.

As part of her job, Zapata oversaw the counting of absentee ballots in Milwaukee. The mayor said the city is investigating whether she might have committed any other offenses.

The ballots were sent to the home of Republican state Rep. Janel Brandtjen, who chairs of the Assembly elections committee and has voiced support for overturning the results of the 2020 presidential election in the state and promoted conspiracy theories about the same. Earlier in the week, Brandtjen’s office said she had received three ballots for military voters she believed to be fictitious. Brandtjen said then she thought someone was trying to show how easy it is to get military ballots in Wisconsin.

The announcement comes five days ahead of Election Day in a cycle where officials are increasingly concerned about threats from within their own organizations. In battleground states such as Wisconsin, elections officials are seeing record partisan poll worker nominations that could put skeptics on the front lines of the voting process.

Zapata’s motive for allegedly obtaining and sending the ballots wasn’t immediately clear. She did not immediately respond to messages left Nov. 3 at phone numbers believed to be hers. Michael Maistelman, an attorney for Zapata, didn’t immediately respond to a voicemail.

But her boss, commission Executive Director Claire Woodall-Vogg, said she thought Zapata was intent on illustrating a vulnerability in the system. She said Zapata had, to her knowledge, never before violated work policies or procedures.

Zapata’s alleged actions echo those of a Racine man who requested and received absentee ballots in the names of lawmakers and local officials in July. That man, Harry Wait, said he wanted to expose vulnerabilities in the state’s elections system. He has been charged with two misdemeanor counts of election fraud and two felony counts of identity theft — charges that could land him in prison for up to 13 years.

Milwaukee County District Attorney John Chisholm said his office was reviewing allegations against Zapata and that he expects charges to be filed “in the coming days.”

In Wisconsin, military voters are not required to register to vote, meaning they don’t need to provide a photo ID to request an absentee ballot.

The Wisconsin Elections Commission and local elections officials who send out and collect ballots have a number of safeguards in place to catch fraudulent absentee ballot requests. The elections commission staff monitors the statewide voter registration system for indications of unauthorized requests. The MyVote website also requires a person requesting a ballot to verify that they are the person asking for it, along with a warning about potential penalties for committing fraud.

Wisconsin Elections Commission Administrator Meagan Wolfe called Zapata’s alleged action “a deeply unfortunate violation of trust” but said election fraud remains extremely rare and is quickly discovered.

“While the actions of this individual set us all back in our efforts to show Wisconsinites that our elections are run with integrity, I have every confidence the upcoming election will be fair and accurate,” she said.

Zapata was fired immediately after the city was made aware that she might have been responsible, and she no longer has access to city computer networks or offices, the mayor said.

Zapata had worked for the elections commission for seven years and with the city of Milwaukee for nearly 10 years, according Woodall-Vogg.

Brandtjen said the episode vindicates the concerns she has raised about elections despite criticism from “the liberal media” and Republicans “who don’t have the backbone to take on the issues.”

President Joe Biden defeated Trump by nearly 21,000 votes in Wisconsin, an outcome that has withstood two partial recounts, a nonpartisan audit, a conservative law firm’s review and numerous state and federal lawsuits. Even a Republican-ordered review that drew bipartisan criticism did not turn up evidence of widespread fraud that would change the outcome of the election before the investigator was fired.

In August, after Wait’s actions came to light, the election commission notified voters whose absentee ballot requests for the primary went to a mailing address different from the one on file to alert them of potential fraud.

Harm Venhuizen is a corps member for the Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues. Follow Venhuizen on Twitter.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us