Making Sense Of A Health Care Bill On A Fast Track

The rollout of the Republican proposed bill to replace the Affordable Care Act has been chaotic, from one senator's frantic search for the bill before its text was released to a lack of consensusamong GOP legislators.

March 13, 2017

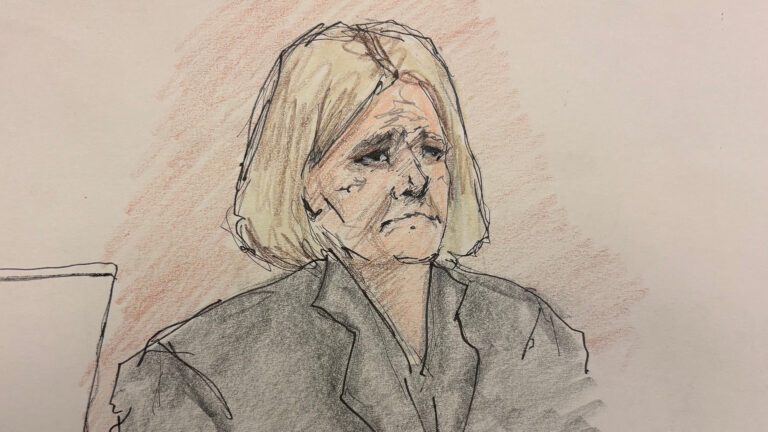

HAN: Donna Friedsam on American Health Care Act

The rollout of the Republican proposed bill to replace the Affordable Care Act has been chaotic, from one senator’s frantic search for the bill before its text was released to a lack of consensus among GOP legislators. In short, the introduction of the American Health Care Act did little to quell the confusion that has spread since Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential election after campaigning hard against the ACA.

Republicans moved to advance the bill before the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office weighed in on it — a breach of legislative custom. House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Janesville, dismissed the forthcoming CBO report as a “pretty piece of paper.” Meanwhile, the White House pre-emptively called into question the CBO’s credibility, despite its reputation as a generally unbiased and accurate, if fallible, source of policy analysis. One analysis by Standard & Poor’s estimated that up to 10 million people could lose insurance under the House Republicans’ plan.

This introduction left public-health experts like Donna Friedsam of the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute trying to piece together a picture of how the AHCA would work. In a March 10, 2017 interview with Wisconsin Public Television’s Here And Now, she offered some thoughts on how the bill’s provisions might shake out for Wisconsinites.

“This is a little unusual in the fast track that we’re on right now, that the House is going ahead and voting on the bill without having the CBO score,” Friedsam said.

In its current form, the AHCA would undo the ACA’s mandate that all Americans have health insurance, instead providing for penalties for people who let their coverage lapse. It would change the structure of health-insurance subsidies and place new emphasis on health savings accounts and high-risk health insurance pools, which offer policies for people who have serious health problems and would normally be considered “uninsurable.”

Friedsam expects the AHCA, if passed, would fall harder on older people than on younger people, on rural residents than urban residents, and on poorer people than wealthier people. In other words, as found in multiple analyses, its changes would largely disadvantage people who helped Trump win. Getting rid of the Affordable Care Act would have significant impact in Wisconsin, where more than 230,000 people have gained health insurance under that law. Wisconsin was among the most-insured states in the nation before the ACA was implemented, but after it was, health insurance rates in the state reached an all-time high in 2015.

“Our rural counties actually have larger percentages of their population enrolled in ACA plans than do our urban counties,” Friedsam said. “We have a fairly significant investment in our state in the Affordable Care Act as it stands today.”

About 84 percent of Wisconsinites who gained coverage under the ACA benefited from the subsidies the law provides. Based in part on income, these subsidies increase and offset some of the increased premiums policyholders are seeing. The Republican plan under the AHCA would cut subsidies, basing them not on income but on age.

Friedsam pointed out that a 60-year old on a low income would have the same subsidy cap as a 60-year-old with a high income.

“While a $2,000 credit might be fairly significant for a young healthy person to be able to buy a fairly thin health insurance coverage because that’s all they need…$4,000 for a 60-year-old low-income person is not going to come near what they would need to purchase their policy,” she said. “It may not even cover a third or a quarter of what they would need to purchase a health-insurance policy.”

Wisconsin had previous experience with high-risk pools between 1979 and 2014, and Friedsam said they had mixed results. At their height, high-risk pools in Wisconsin enrolled about 21,000 people, and even then, policies were highly expensive, she said. This approach more than half a million Wisconsinites uninsured.

Friedsam said Medicaid would likely remain sustainable on a federal level. But under the American Health Care Act’s proposed Medicaid cuts, the program would be harder to sustain on a state level. She’d expect states to handle those cuts by reducing Medicaid eligibility, reducing benefits, and/or reducing payments to health-care providers.

After years of dire assertions by Republicans about the Affordable Care Act, Ryan is now arguing that the law is in a “death spiral,” even as it is gradually becoming more popular among Americans of all political stripes.

Friedsam said the ACA absolutely has flaws, but they’re not impossible to fix.

“Most objective observers would say it’s not the case that Obamacare is in a death spiral,” she said.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us