Local officials seek clarity about Wisconsin's election administration ballot questions

Local election clerks struggle to answer questions about who would be able to set up polling places or print ballots under the wording of two proposed state constitutional amendments related to election administration on Wisconsin's spring 2024 ballot.

Wisconsin Watch

April 1, 2024

Voting takes place on Nov. 8, 2022, inside the Gates of Heaven synagogue in Madison. Election officials are worried that constitutional amendments on the April 2, 2024 ballot will create legal confusion over who can work on Election Day. (Credit: Amona Saleh / Wisconsin Watch)

This article was first published by Votebeat and Wisconsin Watch.

Wisconsinites will vote April 2 on two proposed amendments to the state constitution that could reshape how elections are run in the state — but voters, and many election officials, don’t know exactly how the broadly written proposals would be interpreted by state election officials and the courts.

Election officials said the second proposal could have especially unpredictable consequences. That one seeks to ban anybody besides election officials from performing “any task in the conduct of any primary, election, or referendum.”

How strict would that ban be? Would it mean that election officials couldn’t hire private companies to print ballots or assemble voting machines? Or that they couldn’t ask other city workers to set up polling sites? Officials and experts aren’t sure.

“It’s a very poorly written provision because it is so vague,” said Mike Haas, Madison’s city attorney and the former administrator of the Wisconsin Elections Commission. He said the wording used in the amendment isn’t defined in state law.

Differing interpretations could play out in lawsuits if the measure is enacted.

The two Republican-written ballot questions coming before voters on April 2 are largely a response to 2020, when private groups and outside consultants got involved in funding and assisting election administration across the state and country in the midst of the pandemic.

The first proposed amendment seeks to prohibit the use of private grants or cash donations for election costs. That stems from a national GOP backlash to millions of dollars in election administration grants awarded in 2020 to communities around the country, including more than 200 jurisdictions in Wisconsin. The grants, from Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, flowed primarily through the Center for Tech and Civic Life, a nonprofit.

The second, the proposal that seeks to restrict election-related tasks to election officials only, is meant to address a situation related to outside grants that arose in Green Bay in 2020, when the city worked with a consultant who had ties to outside funders. If the proposal is interpreted broadly, it could force major changes to elections in a swing state during a presidential election expected to spur high turnout.

That amendment could be interpreted to ban some non-election municipal workers from helping with voting-related tasks, such as city police escorting workers transporting ballots or the IT department providing cybersecurity for voter registration systems, Haas said. The proposal could also ban outside workers from transporting voting machines or troubleshooting election equipment, he added.

Some proponents of the amendment say the worries are overblown.

“We do not believe that the proposed amendment covers either printers who print the ballots or the companies that manufacture voting machines,” said Rick Esenberg, president of the conservative law firm Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty, which frequently files lawsuits over questions of election administration. He added that he didn’t think it would prevent non-election city workers from setting up polling sites, either.

But if it did, it’s not clear what election officials would do instead.

“All of those employees of those companies are doing things that, if they didn’t perform those, we would not be able to conduct the election,” Haas said.

Questions about whether the proposal applies to private vendors building voting machines, printing ballots and programming them would likely end up being the subject of a lawsuit, said Dane County Clerk Scott McDonell, an elected Democrat who oversees elections in Wisconsin’s second most populous county.

“It’s sort of nuts,” he said about the proposal. “It is so unclear and, honestly, unthought-out that it would be up to a judge to decide these things.”

Other election officials also said the effort to prevent a repeat of the Green Bay situation creates unanswered questions and may go too far.

“The intent is a good thing,” said Marathon County Clerk Kim Trueblood, a Republican, about the proposal. “I just think there needs to be a little bit more clarification on some of the details.”

Zuckerberg’s donations for grants fired up Republicans

The first ballot question is meant to prohibit grants such as those awarded by CTCL in 2020, which added up to more than $10 million to communities around Wisconsin. Grants were awarded to any eligible community that applied, CTCL said, but most of the dollars in Wisconsin went to Milwaukee, Madison, Green Bay, Racine, and Kenosha — the state’s largest cities and Democratic strongholds.

The amendment’s sponsors, Sen. Eric Wimberger, R-Green Bay, and Assembly Majority Leader Tyler August, R-Lake Geneva, charged in a memo that “targeted private ‘donations’ were shown to dramatically increase turnout for one party.” Former state Supreme Court Justice Michael Gableman, who led a partisan, taxpayer-funded review of Wisconsin’s 2020 vote, also seized on the donations, claiming the grants were “a wave of massive election bribery.”

Academic research has found otherwise. One study, published in October 2023, said that while “counties that favor Democrats were much more likely to apply for a grant, we find that the grants did not have a noticeable effect on the presidential election.”

Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, gave hundreds of millions of dollars to CTCL — funding that was doled out to some 2,500 election departments in 49 states, the nonprofit said. But some Wisconsin communities, including Madison, had received CTCL grants even before the tech billionaire made his donations.

Conservative-allied groups filed lawsuits over the grants, arguing they were illegal under existing state law, but lost in court. State lawmakers then passed a bill to ban them, but Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat, vetoed it in June 2021, saying it would have unnecessarily restricted “the use of resources that may be needed to ensure elections are administered effectively.”

Conservatives then turned to the constitutional amendment, which uses language similar to the vetoed legislation. Governors in Wisconsin can’t veto constitutional amendments.

A sign directs voters on Election Day on Nov. 8, 2022, to a polling location inside the Gates of Heaven synagogue in Madison. Voters on April 2, 2024 will decide on two constitutional amendments affecting election administration. (Credit: Amona Saleh / Wisconsin Watch)

Twenty-seven states now ban, limit or regulate the use of private funds to run elections, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. All those laws were enacted after 2020.

If the proposal passes, the state constitution would be amended to ban government employees from applying for, accepting, expending, or using “any moneys or equipment” donated by an individual or nongovernmental entity in connection with a primary, election or referendum.

As for the second proposal, Green Bay in 2020 accepted more than $1.2 million in CTCL grants, funding that a city official said was needed because of the pandemic. The clerk’s office had exceeded its 2020 budget after the April election, according to an April 2021 report from Vanessa Chavez, who was Green Bay’s city attorney at the time.

Green Bay, through the CTCL grants, was provided access to consultants from the National Vote at Home Institute, the Elections Group, the Brennan Center for Justice, and other groups to help prepare for the election.

One outside consultant, Michael Spitzer-Rubenstein of the National Vote at Home Institute, was particularly involved in planning efforts, according to Chavez’s report. He drew the ire of Gableman, Republican lawmakers and conservative activists after the election.

“In at least one case, private employees played a concerning role in the administration of the presidential election,” Wimberger and August wrote in their memo.

Spitzer-Rubenstein made “recommendations to staff” about logistics, setup and elections operations, according to Chavez’s report, though he “had no decision-making authority” and he “never assisted with any matters involving actual ballots.”

Who can work on elections? Wording is ‘nebulous’

Ahead of the vote on the second proposal, clerks across the state have raised concerns that the measure could prohibit assistance they have come to expect during elections.

Oconomowoc City Clerk Diane Coenen questioned whether the measure would ban city Department of Public Works officials from moving election equipment to polling sites, and Trueblood wondered if it would also prohibit private vendors from printing ballots.

“Am I going to be able to continue?” Trueblood said. “Am I going to have to send ballots to goodness knows where to have them printed? I would rather have our chain of custody locally, where I send them the ballots and I have one person deliver them to my office.”

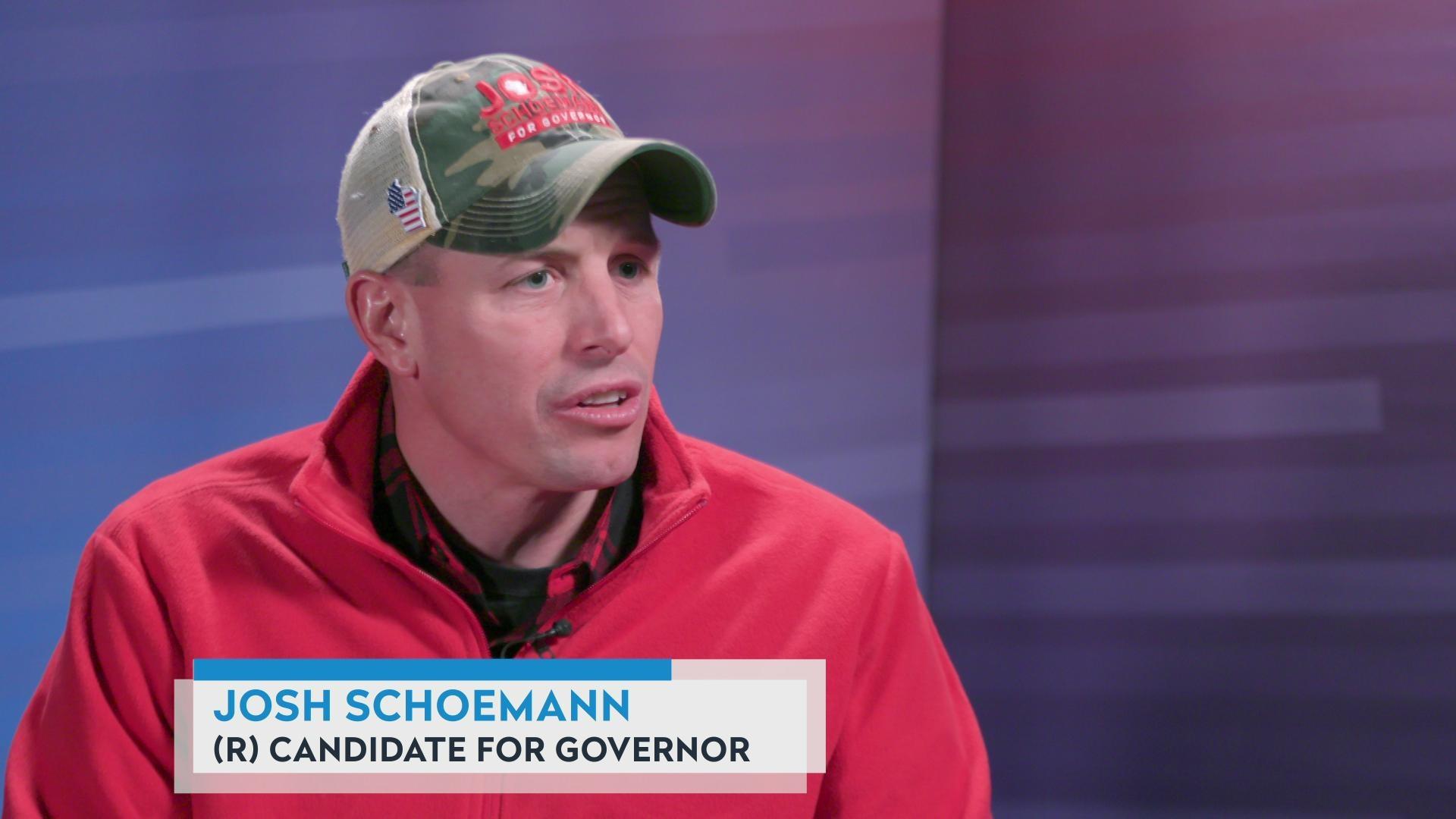

Confronted with clerks’ concerns, Wimberger said that if they’re worried about whether a person is eligible to do an election-related task, they can just tell them they’re “hereby designated” to do that task.

“You just don’t want people collecting ballots that are not even monitored or are completely disconnected from the clerk who’s supposed to be managing all this,” he said. But, he added, “if you’re working at the clerk’s direction, that certainly means you’ve been designated to do the thing that you’re doing.”

But clerks can’t just designate anybody to assist with elections because state law generally requires election officials to be residents of the county they’re working in, said Emily Lau, a staff attorney at the University of Wisconsin Law School-based State Democracy Research Initiative.

That could rule out assistance from the many workers helping clerks with election-related tasks who live outside of the county, or even the state. For example, the company Election Systems & Software helps code ballots for 19 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties, but most of that work is done at the company’s headquarters in Nebraska, ES&S spokesperson Katina Granger said.

Only election officials could perform election-related tasks under a constitutional amendment up for a vote on April 2, 2024. Election officials are questioning whether that applies to private companies that print ballots or service voting equipment. (Credit: Amona Saleh / Wisconsin Watch)

Wimberger suggested it was unrealistic to interpret the provision as banning outside help for all election-related activities.

“You could go down a rabbit hole forever on that,” he said. “I mean, you do use pens. So where’s the ink made?”

He added that a rule from the Wisconsin Elections Commission or an update to state law could rule out any potential disagreements based on when an election starts to be formally conducted.

“There’s going to be a distinction between election preparation and the conducting of the election,” he said. “And I would say that the conducting of the election happens when the polls open or handling ballots.”

But that distinction isn’t written into the constitutional amendment wording, and Wimberger acknowledged that “conducting the election” is “a nebulous term.”

“Things like that have to be nebulous in a constitutional amendment because otherwise there’d be a statute,” he said. “Statutes are more specific, and rules are even more specific than statutes. So I don’t think it could have gotten pared down any more than that.”

Clerks search for clarity, but come up short

Seeking clarity on the provision’s potential impact, Coenen and other clerks have looked through the ballot questions, the proposed language that would become part of the state constitution, and the explanatory statement that state Attorney General Josh Kaul, a Democrat, wrote.

Kaul’s brief statement doesn’t specify what election-related tasks would fall under the amendment’s scope if it passes. State law defines and regulates “how clerks can designate individuals and carry out various tasks relating to elections,” Kaul said.

The statement adds that clerks have power under state law to designate people to perform election-related tasks. But Kaul cautions that should the Legislature change that law, rescinding clerks’ power to designate people to help with election tasks, the new constitutional provision “would bar clerks from designating individuals to assist with election-related tasks.” His statement doesn’t address what might then happen, and clerks say it doesn’t resolve all their questions.

“They’re just too vague for me to get behind them and support them,” Coenen said about the amendment proposals. “And I don’t want to remain neutral because they’re too problematic to be neutral.”

Some clerks say the potential changes and legal issues that could arise if the amendments pass add more variables in an already busy election season.

“We’re trying to do our job. We’re trying to facilitate an election securely, fairly and accurately,” Coenen said. “Our goal is to make sure that every person who wants to vote and is eligible to vote gets to vote. And then we have all this back and forth, back and forth. It’s very concerning and disheartening.”

Stickers often given to voters after filling out their ballots on Election Day are seen on Nov. 8, 2022, at the Capitol Lakes polling location in Madison. Private grants could no longer be used to fund election administration under a constitutional amendment up for a vote Tuesday. (Credit: Amona Saleh / Wisconsin Watch)

When new election-related lawsuits or laws require changes in election administration, the bipartisan Wisconsin Elections Commission generally seeks to issue guidance telling clerks how to implement changes, Commissioner Ann Jacobs, a Democrat, said.

If the proposal passes, Jacobs said, she expects the agency to create new guidance, but it’s unclear how it’ll be worded.

“The problem is that amendment doesn’t really give us a lot of direction, does it?” she said.

Guidance for clerks can be created only if a majority of the six commissioners — three Republicans and three Democrats — approve it. Otherwise, clerks must look to other sources for legal clarification.

Before election administration became hyper-politicized around the 2020 election, the commissioners agreed on many election administration matters, said UW-Madison political science professor Barry Burden, the founding director of the university’s Elections Research Center.

Since then, it has been harder for the commissioners to reach a consensus on many issues, Burden said. Since 2022, they have deadlocked on whether to restrict online access to absentee ballots, rescind guidance allowing drop boxes, and reappoint Wisconsin Elections Commission Administrator Meagan Wolfe, the state’s top election official.

“I don’t know whether, if these items pass, they’ll be able to put together a unified statement about interpreting all of this,” Burden said.

Elections Commission guidance has been challenged in courts, and judges have ordered the agency to rescind or issue new direction.

Between potential litigation and the unclear process ahead at the Elections Commission, the path ahead for clerks if the amendments pass could be murky as they prepare for the presidential election this fall, Burden said.

“Clerks will need to know what’s allowed and what’s not allowed,” he said. “They don’t want to be sued or have their plans disrupted.”

Alexander Shur is a reporter for Votebeat based in Wisconsin. Contact Alexander at [email protected]. This article is made possible through Votebeat, a nonpartisan news organization reporting on voting access and local election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat’s free newsletters here.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us