How Scandinavians Transformed The Midwest, And The Midwest Transformed Them Too

For many Upper Midwesterners in the 21st century, not much could seem more familiar than the marks of Scandinavian influence on regional culture. But there was a time in North American history when Norwegians, Swedes and Danes were considered peculiar outsiders.

November 3, 2016

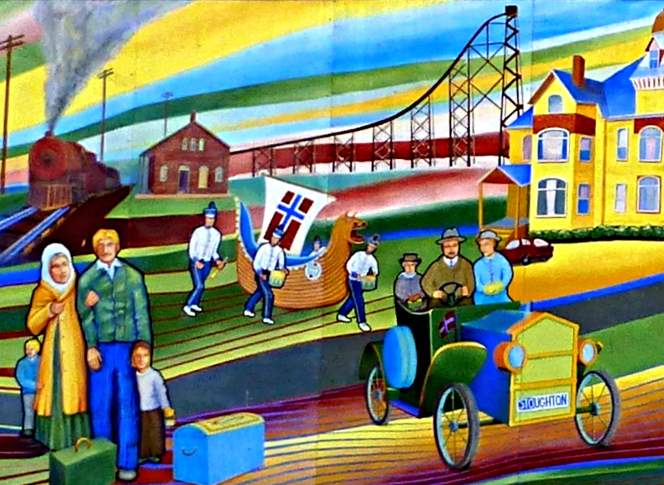

Stoughton Heritage Mural scene with immigrants and Viking ship

For many Upper Midwesterners in the 21st century, not much could seem more familiar than the marks of Scandinavian influence on regional culture. But there was a time in North American history when Norwegians, Swedes and Danes were considered peculiar outsiders, struggling to gain an economic foothold and facing down the nativist resistance every immigrant group to this country has encountered to one extent or another.

About 3 million Scandinavians immigrated to the U.S. between 1825 and 1925, settling across the country but mostly in Minnesota, Wisconsin, North Dakota, and Iowa. In a September 15, 2015, talk at the Wisconsin Historical Museum in Madison, University of Wisconsin-Madison Scandinavian Studies professor Julie K. Allen detailed how these immigrants established themselves so firmly in the fabric of the Upper Midwest, balancing enduring cultural roots with an eagerness to adapt to their new homeland. Her talk was recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s University Place.

Allen explained how Scandinavian-Americans not only introduced many cultural traditions to American life, but also built up enduring institutions, from Lutheran churches to folk schools to ornate wedding outfits. The result, she said, was the development of several “hybrid Scandinavian-American cultures.”

One unique example of Scandinavian culture and its effect on the upper Midwest is the Kensington Runestone. Brought forth by a Swedish immigrant farmer living in west-central Minnesota at the turn of the 20th century, this 200-pound block of sandstone, inscribed with runes, tells a story of a Scandinavian expedition that reached the area by way of Hudson Bay in 1362. Considered by most scholars to be a hoax, the stone’s provenance has nonetheless remained a subject of debate in the region.

In her talk, Allen explained why this artifact matters, regardless of its authenticity. “Public enthusiasm for the Kensington Stone underscored the desire of Scandinavian Americans to demonstrate their close and enduring connection to their new homeland,” she said.

Key facts

- A century-long wave of Scandinavian immigration to the U.S. is considered to have kicked off in 1825, when a boatload of Norwegian Quakers settled in upstate New York, then moved to Illinois.

- Scandinavian immigrants to the U.S. established farms, Lutheran churches, universities, agricultural cooperatives, and newspapers.

- Norway established compulsory primary education in the 18th century, so most Norwegian immigrants who came could read and write.

- Scandinavian immigrants to the U.S. were quick to learn English and adapt to American practices, but also tended to preserve their native cultures.

- Most Norwegians who emigrated never had the means to visit Norway again, but often sent letters back home to encourage family members to follow them to America. But some were more cautious, warning about diseases like malaria, the dangers of financial hardship and crop failure, and American nativism.

- In the “Muskego manifesto,” published in 1845 in a Christiania (Oslo), Norway newspaper, a group of Norwegian immigrans in Muskego declared that despite the hardships they faced, they still valued the American ideals of liberty and opportunity, and did not regret their decision to plant new roots in the U.S.

- The 15th Wisconsin Volunteer Regiment, composed of Norwegians and Swedes, was the only non-English-speaking regiment to serve in the Union Army during the Civil War. Its commanding officer, Hans Christian Heg, was a resident of Muskego, and was active in the anti-slavery movement and the early Republican Party. He died in 1863 after being wounded at the Battle of Chickamauga in northwest Georgia. (In 1925, a statue of Heg was placed outside the east entrance to the Wisconsin State Capitol, facing King Street in downtown Madison; it was a gift of the Norwegian Society of America). The Civil War service of Scandinavians in the Union would integrate them into American society and even helped lay the foundation for Scandinavian-Americans to play a prominent role in politics around the Midwest.

- Nearly half of Minnesota’s governors have been first- or second-generation Scandinavians.

- Rasmus B. Anderson (1846-1936) was a Madison native and UW-Madison professor who helped establish the university’s Department of Scandinavian Studies, which was the oldest in the nation. (This department was merged with the UW’s German and Slavic studies departments on July 1, 2016 amidst ongoing budget cuts.) Anderson was a vehement proponent of Norwegian-American pride, as well as of the Wisconsin Idea. He also believed Leif Erikson, not Christopher Columbus, was responsible for “discovering” America.

Key quotes

- On how the wave of Scandinavian immigration was self-propelling: “It took place in a much subtler, slower way, largely through chain migration…small groups of two or three families would leave together, with five or 10 years between groups.”

- On the habit of Scandinavians essentially transplanting entire villages to the U.S.: “In today’s immigration debates, this kind of dense influx and ethnically centered community construction would indeed be considered an invasion.”

- Reading from an 1871 Harper’s Weekly article that highlighted how strange Scandinavians initially seemed to Americans: “It is curious to see such a heterogeneous crowd. The Swedes are usually distinguished by their tanned leather breeches and waistcoats and their peculiar aforementioned exhalations… the Norwegians, in their curious national dress, consisting of a gray woolen stiff-necked jacket, which covers only about one-third of their back, while in front it slopes down to a greater length and is profusely ornamented with huge silver buttons, set so close together that they overlap each other. Their breeches, of dark woolen stuff, therefrom reach nearly up to their neck behind, only a small strip of jacket with an enormous stiff collar between. You cannot properly say a Norwegian in a pair of breeches, but a pair of breeches with a Norwegian in them.”

- On the intellectual spirit of folk high schools, which originated with Danish intellectual N.F.S. Grundtvig and came to America with Scandinavian immigrants: “Students were expected to learn for love of learning. Less emphasis was placed on knowledge than on an inquiring attitude of mind.”

- On the long-term cultural impact of Scandinavian immigration: “Rather than invading and conquering, they were themselves transformed by the decision to seek out a new and different, ideally but by no means guaranteed better, life, in a land that they could not be entirely sure existed. Once here, they laid claim to this land, by the expenditure of their blood and sweat, as well as through the assertion of long-distant historical claims — both verifiable, as in the case of Leif Erikson, and dubious, as in the case of the Kensington Stone. They contributed their passion for community, for music, for education, for equality, for alcohol, for Christianity, and many other things, that continues to inform and enrich the culture of the Midwest.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us