How did Hmong people find their way to Wisconsin? The answer has roots in America's Secret War

Hmong soldiers served as allies of the U.S. during the Vietnam War, and after facing persecution, many fled as refugees and resettled elsewhere around the world, with the first wave of immigrants to Wisconsin arriving in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Wisconsin Watch

April 13, 2022

Teng Cha, center right, and Chai Yee Cha, left, join other former Hmong soldiers who fought under the direction of the CIA to discuss their plight in 2004 upon the closure of the Wat Tham Krabok refugee camp in Thailand. (Credit: Sharon Cekad / Appleton Post-Crescent)

By Duke Behnke, The Post-Crescent

Ties between Hmong people and the United States date to the early 1960s, nearly two decades before they began arriving in northeast Wisconsin.

Their story as American allies in the Vietnam War is often overlooked, forgotten or ignored.

Hmong are an ethnic group from Southeast Asia with a specific culture and language. In the 19th century, to escape imperialism, they migrated from southern China to the mountainous regions of Laos, Vietnam and Thailand.

During the Vietnam War, the CIA covertly recruited and trained Hmong soldiers in Laos to fight in support of U.S. forces against the North Vietnamese and the communist Pathet Lao. The operation became known as the Secret War.

According to the Hmong American Center in Wausau, the CIA directed Hmong soldiers to:

- Disrupt the North Vietnamese supply lines that ran through Laos along the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

- Provide intelligence about enemy operations.

- Guard a strategic U.S. radar station that was used to direct planes dropping bombs on North Vietnam.

- Rescue downed American pilots.

Long Vue, 54, of Kaukauna was born on the Bouam Long military base in Laos. His dad and uncle defended the radar station used by U.S. forces.

“They would be up in the mountains protecting that night and day, and they could be overrun by (North) Vietnamese soldiers at any time,” Vue said.

After the withdrawal of U.S. forces and triumph by the communist forces, Hmong were persecuted by the victors and forced to flee their homeland. Many spent time in refugee camps in Thailand before they were resettled in Australia, France, Canada, Germany and the United States.

Hmong refugees were legally admitted to the United States and were initially resettled by church organizations such as Catholic Charities and Lutheran Social Services, according to the Hmong American Center.

California, Minnesota and Wisconsin were leaders in accepting Hmong refugees. The first wave arrived in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It included Vue’s family, who arrived in Kaukauna in 1980. The last wave came in the mid-2000s.

(USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin)

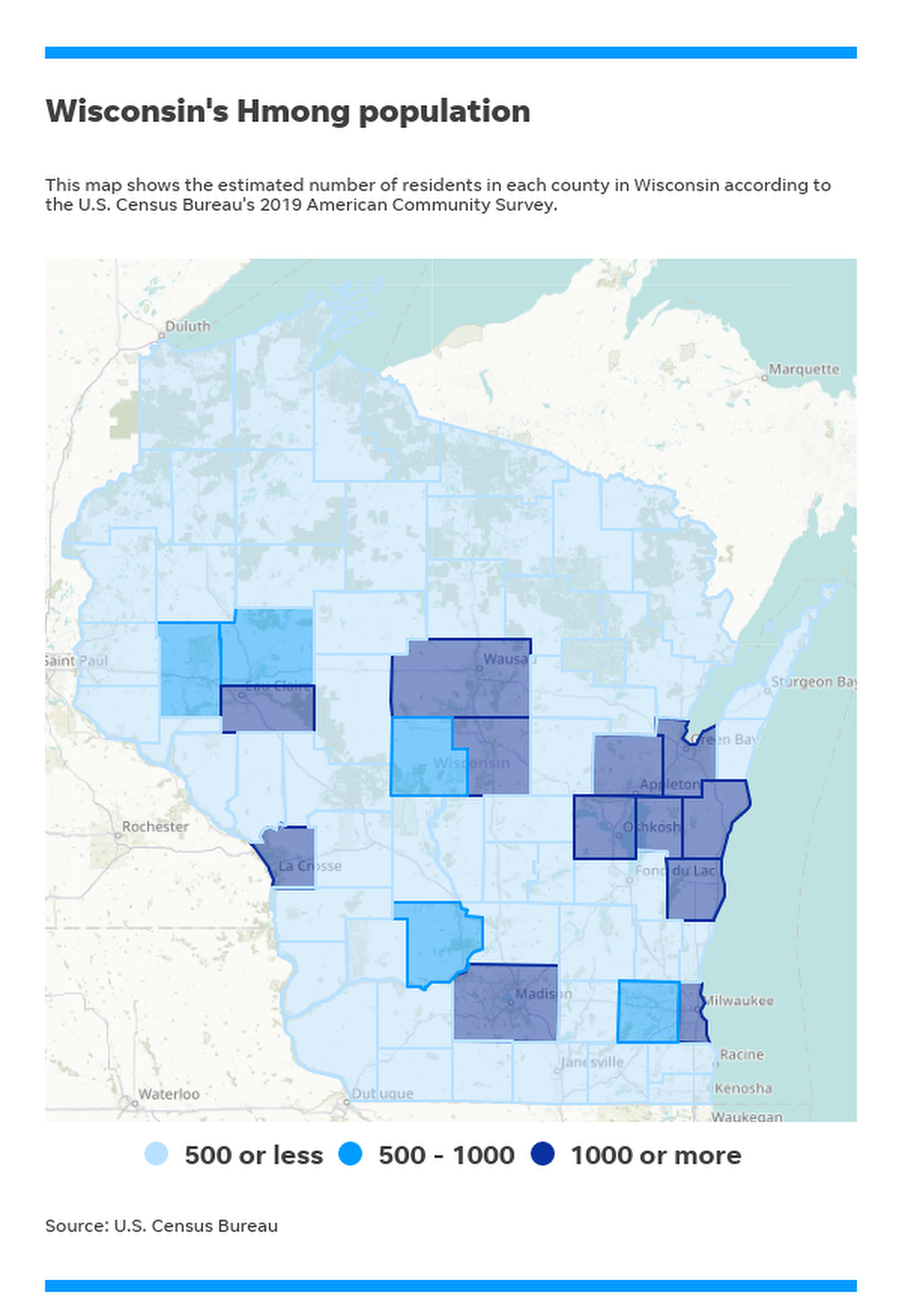

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey, more than 58,000 Hmong people live in Wisconsin, accounting for nearly 1% of the state’s population of 5.9 million.

Cities with a significant Hmong population include Milwaukee, Wausau, Sheboygan, La Crosse, Madison, Eau Claire, Green Bay, Appleton, Oshkosh, Manitowoc, Stevens Point, Wisconsin Rapids, Menomonie and Fond du Lac.

Outagamie County and the Hmong American Partnership of the Fox Valley are working to create a memorial at Plamann Park in Appleton to honor Hmong military veterans who served in the Secret War between 1961 and 1975.

According to the Minnesota Historical Society, between 30,000 and 40,000 Hmong soldiers were killed in combat by the end of the Vietnam War.

Vue said it’s important to recognize the sacrifices of Hmong people.

“We take it for granted, especially our young generation, whether the Hmong or the American kids,” he said.

Contact Duke Behnke at 920-993-7176 or [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter at @DukeBehnke.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us