How copay accumulators affect patient access to medications

Rx Uncovered: Patients who have health plans with high deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums increasingly encounter an accounting tool known as an accumulator that redirects savings from copay cards.

By Marisa Wojcik | Here & Now

August 1, 2025

Many patients are encountering an accounting tool that redirects savings from copay cards.

For decades, the cost of prescription medications has been ever increasing. At the same time, health coverage of these medications has been decreasing, forcing patients to make harder decisions about their health. Rx Uncovered is a series from “Here & Now” producer Marisa Wojcik that dives into the complex systems driving these trends and the stories of patients facing life or death choices. The fourth story is about how health plans use accumulators to divert financial aid away from patients in need.

“I couldn’t believe what I found out when this happened. I couldn’t believe it was legal,” said Tamara Varebrook, a resident of Germantown who lives with painful chronic conditions. She can still live her life — as long as she has her medication.

“I changed jobs, and started over with a new copay and new deductible, and that’s when this hit me — I wasn’t getting my medications. I thought, ‘Why aren’t you sending them?’ They’re like, well, ‘You have a $6,000 balance,'” she said. “I had my first experience with copay accumulators — I had never even heard of them.”

A copay accumulator sounds like an obscure insurance term — and it is.

“I know people don’t understand this if this doesn’t directly affect them,” Varebrook said.

It’s also a growing trend among health plans.

For Varebrook’s conditions, her medication costs her the equivalent of buying a new car every year.

“It’s ridiculously expensive, but it’s the thing that makes me be able to walk and my arms bend and keep my joints moving, so I don’t end up in a wheelchair,” she explained.

To afford her drugs, Varebrook’s doctors told her about patient assistance programs, like copay assistance. It’s often the drug manufacturer helping the patient to afford their own high-priced medication. This kind of financial assistance is referred to as a copay coupon or copay card.

“Meant to help the patients get their drugs and pay down their deductibles, pay down on their out-of-pocket maximums,” she explained.

Here’s how they work. A patient is prescribed an expensive name-brand drug that doesn’t have a generic. Their plan has a high deductible and out-of-pocket maximum, which they must meet before their plan will cover the drug. The copay card provides the financial assistance to cover the patient’s deductible and out-of-pocket max. When those are met, the health plan kicks in and covers all or part of the cost that remains of the drug, potentially saving the patient thousands of dollars.

“It was a life changer. I was pretty low income at the time when a lot of my medical issues started and I would never have been able to afford these medications,” said Varebrook. “And they made a huge difference.”

Until 2023.

One day, Varebrook realized she wasn’t receiving the life-changing assistance — or her medication. She was blindsided.

“They weren’t shipping it, and so I kept calling and saying, ‘Well, why isn’t this shipping?’ They’re like, ‘You owe $6,000.’ And I’m like, ‘What do you mean I owe $6,000?'” Varebrook recalled.

The drug company had provided the copay card.

“I’ve already gotten this and it should be — my deductible at least should be covered,” she said.

The problem was the financial assistance no longer covered her. Varebrook shared what the pharmacy told her.

“‘If you don’t pay for it in full, you are not getting your medication,’ and I went months without,” she said.

Varebrook had recently started a new job, where her health plan contained a copay accumulator.

“I spent countless hours on phone calls — I can’t even tell you how upsetting it was,” she said.

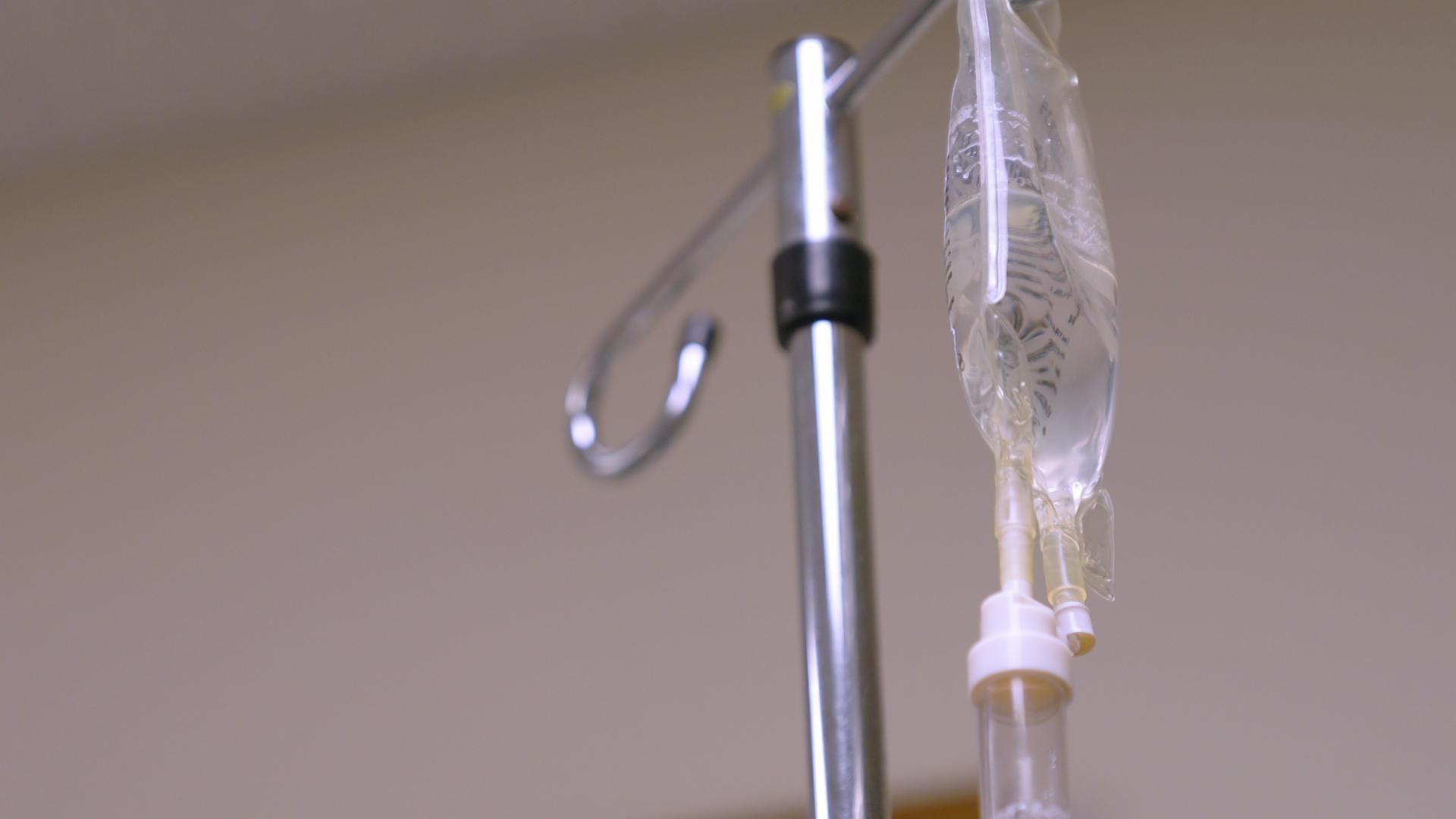

The accumulator is a relatively new tool used by health plans and pharmacy benefit managers. An accumulator takes the financial assistance — the copay card — and only applies it to the total cost of the drug. It does not count toward the patient’s deductible or out-of-pocket maximum.

In other words, the patient no longer saves money. The health plan saves money by taking the full amount of the copay card, still collecting the deductible and out-of-pocket maximum paid by the patient.

“This is a very scary moment for me just knowing a lot of other people with MS,” said Jim Turk, a Madison resident who has multiple sclerosis, or MS — A disease that attacks the body’s nerves. There’s no cure, only treatment.

“If you’re on drugs — I mean, that’s your lifeline — that’s something that’s preventing that, or at least slowing that down significantly from happening,” he said. “They don’t have as much stress in their life either, and the stress in their life can also exacerbate the symptoms, so it’s just this vicious circle.”

Turk is an advocate for people with MS, knowing the struggles firsthand.

“I look at a list to see what all the drugs cost. Ocrevus, the one that I was on last — which was actually the newer drug — was one of the cheaper drugs and that was I think $70,000 or $80,000 dollars a year, which I can’t afford,” he explained. “I’m on a disability, and so insurance was obviously covering that.”

Having been the recipient of copay cards, Turk stresses their importance for patients to survive.

“You have to make the choice between paying for your drugs that might be a lifesaver or paying for groceries,” he said. “And obviously there’s no choice there or paying for rent. and that’s really what it comes down to.”

And a copay accumulator, makes that choice even harder.

“They’re essentially designed to be confusing,” Turk said.

“I thought, ‘Holy cow!’ Well, in 21 states, it is now illegal, but not Wisconsin,” Varebrook said.

Other states have outlawed accumulators, and a bill in the Wisconsin Legislature would as well. At a hearing, health plans and pharmacy benefit managers spoke in opposition.

“This bill does nothing to control the soaring prices of prescription drugs set by pharmaceutical manufacturers, but instead rewards drug makers for steering patients towards more expensive brand name drugs,” said Patrick Lobejko, a lobbyist with the Washington, D.C. firm America’s Health Insurance Plans.

They say copay cards are a ploy by pharmaceutical companies to get patients to take expensive name-brand drugs.

“Rather than benefiting those in financial need, a lot of these coupons from manufacturers act as an inducement to move to higher-cost products,” said Sharon Faust, chief pharmacy officer with the Madison-based Navitus Health Systems, which provides pharmacy benefit management services to state employees.

Supporters of accumulators say they lower costs for everyone by saving health plans money, not just one patient. Others refuted these claims, though.

“Nearly all copay assistance programs from manufacturers are for drugs with no generic alternative,” said Bill Robie, senior director of government relations with the National Bleeding Disorders Foundation. “Copay assistance increases medication adherence.”

Robie described the costs that come with patients not taking their medications.

“Studies have found that morbidity and mortality associated with poor medication adherence cost the U.S. health care system $528 billion annually,” he said at the hearing. “Non-adherence can lead to treatment failure, resulting in poor outcomes, such as worsening of condition, admission to the emergency room and hospitalization, and requiring new prescriptions to treat subsequent comorbidities, which results in higher cost to the entire health care system. That is what will increase premiums.”

This analysis rings true for Varebrook.

“The specific drug is not the only cost of chronic disease,” she said. “Chronic disease causes people to miss work, end up in emergency rooms, hospital bills.”

Drug manufacturers do not like accumulators, because the assistance doesn’t go to help the patient. Varebrook fears they may end up not providing assistance at all.

“I’m afraid that the drug companies, the pharmaceutical companies, stop the programs because they’re not helping the patients. That would be a real nightmare, because then everybody would suffer,” she said. “This is where we’re at in Wisconsin now. I feel bad for everybody who has a child or any adult that runs into these issues, because most people are not prepared with that kind of money, and you aren’t going to get your medication.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us