From 'dream' property to nightmare: When Wisconsinites pay the price for pollution they didn't cause

Under state law, individual property owners in Wisconsin can be left on their own to mitigate environmental hazards created under previous ownership, without enough assistance to cover cleanup costs.

Wisconsin Watch

February 1, 2023

Caution tape on Zach Skrede's property in the town of Easton, in Adams County, is seen on Oct. 10, 2022, warning about the presence of asbestos. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

After 17 years in the Air Force, Zach Skrede was thrilled to move back home.

Skrede, who grew up about a half hour south of Madison, moved to the town of Easton in Adams County, Wisconsin, in 2019. He took a job at the Oxford Federal Correctional Institution — a medium security federal prison — as a facilities engineering technician to help in part with a roof renovation project.

A few miles away from the prison, he bought a one-story house on Elk Avenue with 20 acres of property.

Skrede, 38, had big dreams for the land. He envisioned building a fire pit, creating a camping space and hosting friends. After he was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2020, he planned to build a more accessible house on the property to accommodate his health needs — a place where he could settle down with his fiancé Kristen and his 16-year-old son Justin, who visits for summers and holidays.

In hindsight, Skrede said he should have realized there was a catch.

“I should have known it was one of those too-good-to-be-true things,” he said.

Zach Skrede purchased an Adams County property in 2019, only to find some asbestos-containing materials left by the former owners, the roofing company Brazos Urethane. Skrede is seen on the property on Oct. 10, 2022. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

One day at work, Skrede told a colleague at the prison about his property tucked away in the woods. The co-worker started asking questions about what the house and basement looked like.

“He started saying, ‘Oh god, yeah that house sounds familiar. … I think that’s the Brazos house you got,'” Skrede said. “And I asked him, ‘Okay — what the hell is that?'”

That’s when Skrede’s dream property became a nightmare.

Roofing company owned house

It turns out Skrede’s land had been owned previously by Brazos Urethane Inc., a Texas-based roofing contractor. Brazos’ owner purchased the property in 2015 when the company was hired to complete part of the prison’s roof renovation — the same project Skrede was hired to help finish.

During the project, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration cited Brazos for workplace safety violations at the prison. Then, the company committed other violations — including illegally dumping roofing debris onto what is now Skrede’s property. That waste contained asbestos, a carcinogenic mineral.

In 2015, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources investigated a complaint about possible improper disposal of asbestos containing material on the Elk Avenue property that was removed from the roof of a building inside the Oxford Federal Correctional Institution in Oxford. (Credit: Courtesy of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

After receiving a complaint, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources inspected Brazos’ property in November 2015, where the agency discovered it was being used to dump roofing waste. Samples of the debris tested positive for asbestos. Brazos provided documentation of the cleanup, and the DNR closed the case.

But the DNR’s well-intended remediation plan was a flop.

Five years after the initial cleanup, and three months after Skrede bought the land, he discovered piles of asbestos-containing material hidden in the trees and partially buried across the property. Beyond the potential health consequences, Skrede felt a drastic financial hit. According to an appraisal he commissioned in early 2022, the property, which he bought for $265,000, was estimated to be worth $5,000. The cleanup could have cost him as much as $1.2 million.

When Skrede confronted the DNR in March 2020 about the remaining asbestos, he found himself caught in a tangled web of bureaucracy and inaction that lasted for over two years. It was only this October that Skrede, Brazos and the DNR reached an agreement to clean it up. Between legal help and remediation estimates, Skrede has spent nearly $25,000.

‘Innocent buyers’ not always protected

Skrede’s situation echoes the difficulties that so-called innocent buyers across Wisconsin face when someone else contaminates their property. From manure-tainted groundwater to PFAS in drinking water, individual property owners can be left on their own to mitigate environmental hazards without enough state funding to cover cleanups. Under state law, property owners are sometimes even forced to clean up previous contamination.

In recent years, Wisconsin lawmakers have submitted bipartisan bills to help some innocent buyers, but those measures failed to pass.

The DNR and other task forces have not quantified how many individual property owners face this issue. However, Rob Lee, an attorney with Midwest Environmental Advocates who specializes in hazardous substance regulation, said innocent buyer situations are not unique.

“There’s been certainly people and businesses who have bought property … (and) had no idea because it (contamination) wasn’t disclosed,” Lee said. “That’s a very real issue. There are people in communities all across the state who find themselves in this place where they aren’t culpable, really, for the discharge but are nevertheless liable for it.”

Roofing material, some of which was found to contain friable asbestos, is seen on the Elk Avenue property in Adams County during a DNR inspection in 2015. (Credit: Courtesy of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

In a statement to Wisconsin Watch, the DNR said it lacks “sufficient information” to determine how the asbestos-containing material remained on Skrede’s property and will not pursue further action against Brazos following the October cleanup.

“The materials identified in 2020 are the same type of roofing material that was identified in 2015,” the DNR said. “However, the department cannot speculate on what may have happened and must make decisions based on fact.”

Brazos Urethane did not return multiple requests for comment.

Even with the cleanup finished, Skrede’s fight to fully restore the property — and make back all the money he has lost — is far from over.

“The first call to the DNR… right then and there, they should’ve said ‘Holy cow, yeah we missed something. What can we do to make it right?'” he said. “Instead, they turned the opposite way and said, ‘What can we do to make this go away as fast as possible?’ I guess there was really no interest in actually resolving the issue — it was just ending the issue.”

Brazos: ‘Environmentally sound process’

Asbestos is a heat-resistant, carcinogenic mineral that was widely used in construction as an insulator. It is estimated to cause 40,000 U.S. deaths each year and is linked to conditions including asbestosis, lung cancer and mesothelioma. Fifty-five countries have banned asbestos, but not the United States.

DNR staff determined Brazos had dumped at least 150 cubic yards of asbestos-containing material. According to the DNR’s inspection report, the material was “friable,” meaning it is easily pulverized into fibers that could be inhaled — the most dangerous form of asbestos.

In 2015, a state Department of Natural Resources inspection found black-and-white speckled material 1-3 feet deep piled up or used to fill in holes in a road on Zach Skrede’s property. Some of the roofing material was found to contain friable, or loosely bound, asbestos — the most dangerous form. (Credit: Courtesy of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

The DNR cited Brazos for illegally dumping the asbestos-laden material and alleged violations of other air pollution and solid waste laws.

In its defense, Brazos representatives claimed employees separated out the asbestos-containing material so the “biodegradable” layers could be used as a road base. Multiple DNR emails rebut that the material could safely be reused.

In an email to DNR officials, Howard Wallace Scoggins III, the owner of Brazos Urethane, said the company thought “spreading the material on the property would be the most environmentally sound process.”

Problems start at the prison

According to documents obtained by Wisconsin Watch, OSHA separately fined Brazos for three violations during the roof removal project.

Brazos received two citations for failing to use proper safety measures to prevent employees from falling off scaffolding and the roof. Another citation was for failing to monitor employees’ exposure to a chemical in roof foam linked to respiratory conditions.

OSHA also investigated concerns of prison employees, regarding possible exposure to asbestos. The employees filed an additional complaint through their local union, internal DNR documents show. But air monitoring during OSHA’s one-day inspection found no violations.

The complaints claimed Brazos employees threw debris to the ground without a chute, creating a hazard. However, OSHA found a chute was used on the day of their inspection. The DNR alleged similar conduct in a notice of violation letter, including that the company cleared off the roof with a leaf-blower and threw dry asbestos-containing material down an open chute. That notice did not lead to any enforcement action.

- Brazos Urethane, Inc., employees are seen during a 2015 roofing project at the Oxford Federal Correctional Institution in Oxford, Wis. (Credit: Courtesy of Occupational Safety and Health Administration via Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

- Brazos Urethane, Inc., employees pour material down a chute during a 2015 roofing project at the Oxford Federal Correctional Institution in Oxford. (Credit: Courtesy of Occupational Safety and Health Administration via Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

In a statement to Wisconsin Watch, the federal Bureau of Prisons did not answer specific questions about the case but said it has procedures to engage with staff and employee unions to ensure compliance with federal and state environmental, health and safety laws and regulations.

Botched cleanup

A similar scenario played out at the Elk Avenue property cleanup, according to DNR records obtained by Skrede and Wisconsin Watch.

The DNR ordered Brazos to clean up the asbestos-containing material until it was “cleared to bare ground” with “no indication of waste material visually evident.”

The company started the cleanup at the end of November 2015. In the initial notice of violation, the DNR said department staff would “need to observe the site upon completion to determine that the clean-up is adequate.” On Dec. 4, 2015, DNR staff inspected the work.

But the cleanup was not yet complete: The company continued to haul waste off the property through Dec. 10, 2015.

The DNR said in a statement that it found “one pile of material” that remained on the site during their Dec. 4 inspection, which the agency ordered Brazos to pick up. The department used waste manifests and photographs provided by Brazos to close the case. The company paid a $3,057.50 fine for violating waste disposal requirements.

Zach Skrede bought this house on Elk Avenue in the town of Easton with 20 acres of land. He had big dreams for it but then he discovered the property was contaminated with asbestos-containing roofing material. “It’s been absolute hell,” he says. Skrede’s house is pictured on Oct. 13, 2022. (Credit: Courtesy of Zach Skrede)

Five years later, after Skrede discovered patches of black, asphalt-like material spread over his property and learned the DNR had ordered a cleanup, he wondered: How had they missed it?

Lee, the Midwest Environmental Advocates attorney, said the DNR must rely on responsible parties to dutifully complete cleanups due to legal requirements set by the Legislature and resource limitations. Lee described it as a “desktop review” in which the department monitors the test results and documents provided by the responsible party before closing out a case.

“There is a level of trust built in there (for) responsible parties. It’s in their interest and DNR’s that everybody’s above board about what is happening,” Lee said. “But if it’s not, it can be difficult for the DNR to show that.”

In June 2020, DNR enforcement specialist Deborah Dix initially advised Skrede to hire a contractor and have it cleaned up himself. Dix had been involved in the 2015 inspection as well.

The DNR ended up conducting another site inspection in August, after which the agency reopened the case against Brazos, and again ordered the company to clean up the property.

Evidence denied, cleanup delayed

But a series of conflicts stalled the cleanup for about two years. Brazos and the DNR declined to recognize the asbestos-containing material as friable — contradicting the department’s own 2015 assessment that it was friable, or loosely bound together.

Henry Anderson, a retired state epidemiologist who studied asbestos, said when asbestos is friable, it is easier to inhale the toxic microscopic fibers, which can scar lungs and kill cells. Asbestos can remain suspended in the air, he said, and people who are exposed must take special care to avoid shedding it in enclosed spaces.

“The risk is not knowing about it,” Anderson said. “It’s a prevention thing, if you’re aware of it.”

But Skrede didn’t know about the asbestos. He mowed the lawn, his dogs played in it and he walked through the contaminated areas — regularly exposing himself. Skrede fears the agency’s non-friable determination could hurt his chances for financial compensation for future medical problems.

Ned — and his owner Zach Skrede — stroll on their Adams County property on June 18, 2021. Skrede purchased his house and the surrounding land in 2019, only to find large deposits of asbestos-containing materials left by the former owners, the roofing company Brazos Urethane. He worries about his own health and that of his dogs, Ned and Maple. (Credit: Will Cioci / Wisconsin Watch)

He worries most about his son, who was first exposed when he was 14. It can take decades for the effects of asbestos exposure to materialize.

“Would you be happy about just getting a random cough at 30?” Skrede said. “It’s not like I’m demanding millions of dollars from them or anything like that — just to have some sort of medical reassurance down the road.”

The DNR said in a statement that the 2015 asbestos was deemed to be friable, and the 2020 inspection found content “consistent” with the 2015 findings. The department did not take samples to determine friability in 2020 but said the material was ultimately handled as if it was friable in the 2022 cleanup.

The friability of asbestos also impacts how carefully it must be handled, which can increase cleanup costs. Skrede said one remediation estimate that classified the material as non-friable was for about $85,000. Another non-friable estimate was as low as $14,050. But an estimate commissioned by Skrede that classified the material as friable was for $1.2 million.

Liability question

Skrede also objected to Brazos handling the cleanup. He likened it to “allowing criminals to come back to a crime scene, cleaning up their own evidence and scooting back out of town, scot free with no further action.”

“It’s pretty messed up,” he said.

Zach Skrede investigates a pile of asbestos-containing material on his property in Adams County on June 18, 2021. Skrede purchased the home and the surrounding land in 2019, only to find some of the harmful material left behind by the previous owners. (Credit: Will Cioci / Wisconsin Watch)

However, under the “spills law,” Wisconsin’s flagship regulation addressing environmental contamination, Skrede didn’t have much of a choice but to let Brazos proceed with the cleanup.

The spills law holds that anyone who causes, possesses or controls a hazardous substance discharge is liable for cleaning it up. Since Skrede is the current property owner, that means he could be held financially responsible for the cleanup if he did not let Brazos complete it, according to John Robinson, a former DNR official who enforced the law.

Skrede initially refused to let Brazos onto his property, but the DNR responded with a letter that said he may have “to complete the clean up at (his) own expense” — which Skrede perceived as a threat.

“They’ve already made it clear that they can and will make me the responsible party for it,” he said.

Some Wisconsinites face contamination alone

While the DNR first looks for the original polluter, Lee said the nature of the spills law means people may have to pay for contamination they didn’t cause.

“The whole point of the spills law is to shift the cost of cleanup on those who most appropriately bear that burden,” Lee said. “It may not always be the person who had the 55-gallon drum and was dumping it into whatever water body — but, the point is, that the state and the taxpayers shouldn’t have to pay that burden.”

While some Wisconsinites are held legally liable under the spills law, private individuals in general have few public resources to help pay for remediation. People can sometimes buy a property without knowing about previous contamination, or contamination can spread from one source to other properties. This is a common problem with nitrate — one of Wisconsin’s most common groundwater contaminants which comes from manure, fertilizer and septic systems.

A sign on Zach Skrede’s property in the town of Easton in Adams County warns about the presence of asbestos. The contracting company Hogan Environmental Cleaning, LLC is seen preparing to clean up material that had been deposited by the land’s former owner, Brazos Urethane. Photo taken Oct. 10, 2022. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

Individuals can sue the original polluters if they didn’t disclose contamination. But Robinson said this route can be expensive and time-consuming. “Legacy” contamination, in which the company or individual responsible for contamination is no longer around, is another problem.

“There are other funds that will pay for new wells or other things to protect those innocent parties, but there’s not enough money,” Robinson said.

For example, Gov. Tony Evers launched a $10 million grant program in August to help people replace or reconstruct contaminated private drinking water wells. The program is expected to help just over 1,000 households.

However, a report commissioned for the Legislature estimates that at least 42,000 private wells fail to meet the health requirements set for nitrate. The cost of replacing those wells is over $440 million.

‘Innocent purchasers’ legislation stalls

The Wisconsin Legislature has recently tried to help “innocent purchasers.” Bills proposed in 2017 and 2021 would have created liability exemptions for buyers who purchased properties in between the enactment of the spills law in 1978 and mandatory disclosure laws in 1992, which require anyone selling property to disclose such defects.

The DNR does not track the legal status of responsible parties. However, the department estimated that the 2021 “innocent purchaser” bill would have helped 5-10% of 16,600 known sites documented under the spills law.

In a memorandum, the Wisconsin Brownfields Study Group, a subcommittee of scientists, attorneys and researchers, said the lack of resources to help individuals pay for remediation compared to the numerous funding mechanisms available to municipalities and businesses “raises a question of fairness of the current system.”

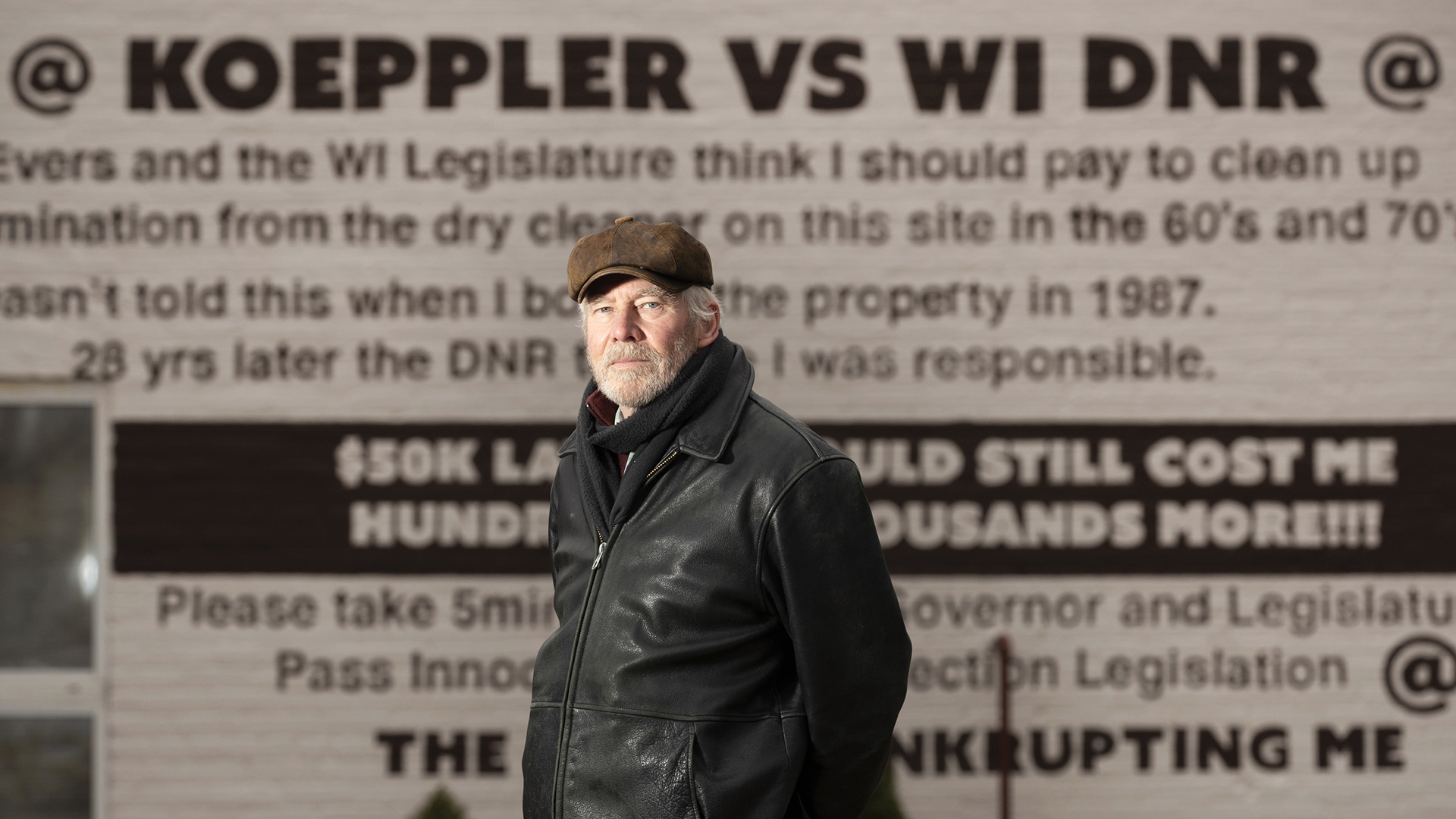

While the legislation would not help Skrede, it would aid Ken Koeppler, a Madison resident who discovered in 2015 that a property he purchased in 1987 was a former dry cleaning site. Since the DNR named him the responsible party, Koeppler has spent over $50,000 on remediation, legal services and other costs with “no end in sight.” Over the next three years, he estimates he will spend an additional $100,000.

“I was under the impression that if … I just did this one more step of the investigation, then perhaps we could get this cleaned up,” he said. “But I have since learned that there’s a long way before that can be closed. It seems like I was getting nickel and dimed until I just said I don’t have any more money to spend on this.”

Ken Koeppler is being held liable for contamination beneath a building he owns in Madison, despite the fact he was never involved in the dry cleaning business that operated there in the 1950s and 1960s. The building had been converted into residential housing before he purchased it in the 1980s. He is shown Nov. 29, 2021 in Madison. (Credit: Mark Hoffman / Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

Despite bipartisan support, both bills failed. In a letter to the Legislature, DNR representative Christine Haag said the legislation could hamper the DNR’s enforcement of the spills law, which is already under threat due to a lawsuit that challenges the agency’s ability to mandate cleanups for unregulated contaminants, such as PFAS, sometimes called “forever chemicals.”

In a statement, the DNR said the “innocent purchaser” legislation “did not ensure that the public is protected from exposure to contamination” and could have created hundreds of brownfields, which are properties that are not used or developed due to environmental contamination.

After the legislation failed, the DNR said its Remediation and Redevelopment program continued talks with legislators about a proposal known as “Revitalize Wisconsin,” which would provide grants and services to local governments and private parties that did not cause the pollution to fully cover cleanup costs. The proposal remained in draft form when the Legislature adjourned last session, but the department is in preliminary conversations about the proposal for the upcoming legislative session.

‘Who pays for it?’

Other states offer a cautionary tale about liability exemptions. In Michigan, home to a liability standard looser than the spills law, an estimated 14,000 sites lack a designated responsible party. State funds to address these brownfields are severely lacking, meaning thousands of sites remain contaminated and undeveloped.

Making financially sustainable changes and avoiding a situation like Michigan’s would require the Legislature to provide more funding to help unwitting property owners, Robinson and Lee said. “If you shift liability, liability doesn’t go away. The problem — the degradation of the environment — doesn’t go away,” Robinson said.

“At the end of the day, who pays for it?”

When Zach Skrede bought this property in rural Adams County, he envisioned building a large fire pit and a camping area for friends. After he was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2020, he planned to build a more accessible house to accommodate his long-term health needs. But his dreams were tainted after he discovered asbestos on the land. Photo taken on Oct. 10, 2022. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

According to the DNR, it would cost $62 to $416 million to investigate and clean up all the properties that would have been exempted under the 2021 “innocent purchaser” legislation.

State-funded cleanups recover their costs — and then some, research shows. The state’s $121.4 million investment to convert brownfields into usable properties recouped $1.77 billion from tax revenue generated by new occupants — a more than 14-fold return, according to the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater Fiscal and Economic Research Center.

Regardless of the cost or return on investment, Koeppler believes the state must find a middle ground.

“The fact that funding doesn’t exist to do everything necessary is not a justification to destroy some innocent property owner’s life and bankrupt them,” he said.

State’s system ‘wildly ineffective’

After over two years of haggling with the DNR and Brazos, Skrede’s property was finally cleaned up in October. The department made three site visits, twice directing Brazos that more cleanup was required before the agency was satisfied.

The contractor at the site removed up to 1,500 cubic yards of roofing material debris — five times more than originally estimated. That’s enough to fill about 100 concrete mixer trucks.

The DNR officially closed Skrede’s case on Nov. 30. In a statement to Wisconsin Watch, the DNR said Brazos’ completion of the cleanup “serves the regulatory purpose” and would require no further action. The agency said it lacked resources for additional investigation, which they said “appears unlikely to advance this regulatory outcome.”

“It just kind of speaks volumes for the public service that we pay for to handle these issues and protect the people and environment in the state,” Skrede said. “They’re just wildly ineffective.”

However, the Environmental Protection Agency continues to investigate the case. An EPA spokesperson said the agency cannot comment on pending or active enforcement actions.

Skrede’s property is seen on the third day of cleanup, on Oct. 12, 2022. The cleanup, which had been stalled for over two years, revealed more debris than the contractors expected to find. According to DNR documents, the contractors anticipated they would uncover up to 1,500 cubic yards of material — five times more than originally estimated. (Credit: Courtesy of Zach Skrede)

Skrede is also pursuing legal action to recoup his financial losses and cover potential future health problems, including a lawsuit against the real estate agent who sold him the property.

He seeks more proactive mechanisms to protect property owners, such as a public database that would allow potential buyers to investigate previous contamination on the land. Currently the state does not mandate solid waste tracking.

The DNR has fielded past proposals for creating a database, according to Robinson, who called such an outcome “ideal.” Currently, different branches and programs of the agency collect information in various formats for separate databases, some internal and some public.

Unified database expensive

In a statement to Wisconsin Watch, the DNR said the agency has no current plans to construct such a database, citing a lack of funding and statutory authority to curate the necessary information.

“It takes a lot of time and effort to set up those systems,” Robinson said. “They (DNR) have not made that investment.”

Zach Skrede is seen on his property in the town of Easton, in Adams County, on Oct. 10, 2022. Skrede purchased his house and the surrounding land in 2019, and he did not know asbestos-containing material was on the property. Since then, he has had to work with the state Department of Natural Resources, and the original polluter, Brazos Urethane, to get it cleaned up. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

With his property cleaned up, Skrede’s dreams have finally come back into focus. He plans to start building a house to accommodate his looming health problems the moment the grass grows back.

He can’t predict whether he will be made whole again — financially or emotionally.

“You wanna have a little more hope in the system than that, but when it comes out like this, it leaves a pretty bitter taste in the mouth.”

Former Wisconsin Watch intern Dana Brandt contributed to this report. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us