Foxconn's 'State Visit Project' And The Art Of Relationship Building

The confusion over Foxconn paints a picture of different ways politics and industrial development are conducted in China versus the United States.

February 7, 2019

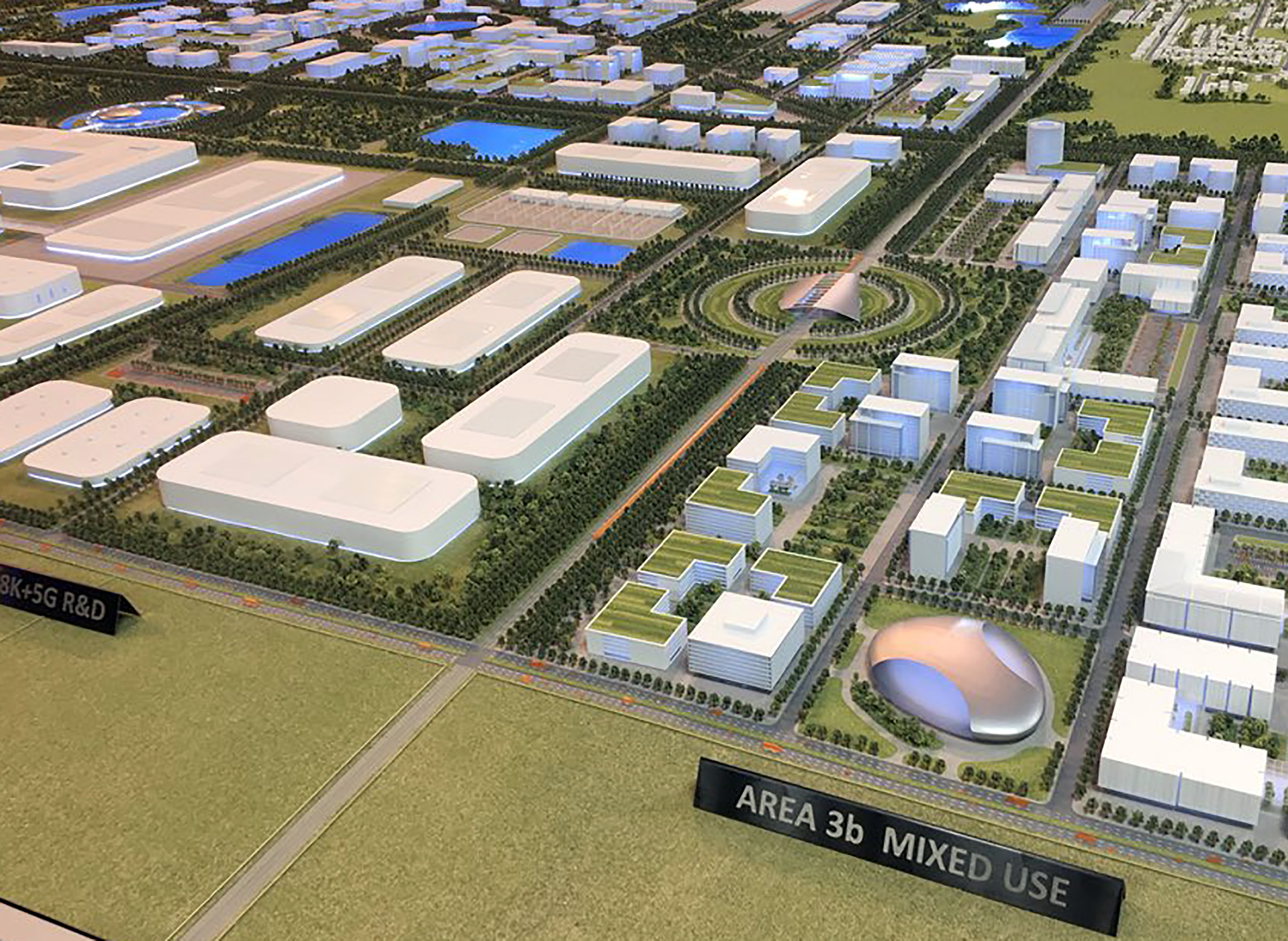

First vertical construction at Foxconn site in Mount Pleasant

Over the course of just one week, Wisconsin has witnessed considerable back and forth on the Foxconn factory project in Mount Pleasant. Shortly after the news hit the headlines that the factory was off, it was back on again.

I’m not privy to the parties on either side of this deal, but I have been inside a number of LCD factories, including one of the newest Gen 10.5 fabs like the one that was originally promised. So I understand some of the challenges in a project like this. For me it paints a picture of different ways politics and industrial development are conducted in China versus the United States.

First, some background on LCD display

Flat-panel liquid crystal display (LCD) screens are one of today’s modern technological wonders. They are the key component inside televisions, computer monitors, smartphones and a proliferating range of gadgets that display information electronically.

LCD screens are manufactured by assembling a sandwich of two thin sheets of glass. On one of the sheets are transistor “cells” formed by first depositing a layer of indium tin oxide, an unusual metal alloy that you can actually see through. Then a layer of silicon is deposited, followed by a process that builds millions of precisely shaped transistor switches. Each step has to be precisely aligned to the previous one within a few microns (a human hair is typically 40 microns in diameter).

On the other sheet of glass is an array of millions of red, green, and blue dots in a black matrix. Then tiny amounts of liquid crystal material are dropped into the cells on the first sheet and the two sheets are glued together. The two sheets must be aligned so the colored dots sit right on top of the cells, and they can’t be off by more than a few microns in each direction anywhere. Then this glass sandwich is covered with special sheets of polarizing plastic, and the sheets are cut into individual “panels” – a term that is used to describe the subassembly that actually goes into a TV or phone.

For the sake of efficiency, it’s best to make as many panels on a sheet as possible, within the practical limitations of how big a sheet a manufacturing process can handle at a time. The first modern LCD fabs established in the early 1990s made sheets the size of a single notebook computer screen, but this size grew over time. A Gen 10.5 “mother glass” sheet is 2940 by 3370 mm (9.6 by 11 ft.). The sheets of glass are only 0.7 mm thick, so as they are extremely fragile and can really only be handled by robots. With this size sheet, it’s possible to produce eight 65 in. or six 75 in. TV screens at once.

Building a Gen 10.5 fab in Wisconsin was never going to be easy

A factory like the one originally promised in the deal between Foxconn and the state of Wisconsin would have been enormous. They have to be built on a massive foundation that will provide stability to the precision production equipment. In addition, that equipment has to operate in a cleanroom so that dust and particle contamination can be kept away from the screens.

The factory I visited in Hefei, China in 2018 was 1.3 km (about four-fifths of a mile) from one end to the other, and it had 440,000 square meters (close to 5 million square feet) of hyper-clean manufacturing space, filled almost entirely with robotic machines that performed the production steps.

Factories like this are surrounded by supplier factories to provide just-in-time delivery of critical components, like the mother glass. The glass is fragile, so most factories in Asia have a glass factory across the street, with the glass sheets fed via an underground tunnel. The main factory costs a lot to build, with a price tag in the multiple billions of dollars for a state of the art Gen 10.5 fab.

Given these scales and requirements, pretty much all fabs built in Asia are dependent on subsidies for their construction.

Foxconn received a huge subsidy from the state of Wisconsin, but it actually wasn’t enough to meet the conditions common at fabs in Asia. The company’s glass supplier Corning, which operates a factory in Kentucky didn’t receive any subsidy. Without its own subsidy, Corning actually couldn’t afford to build a plant adjacent to Foxconn’s that would be competitive. And those Gen 10.5 mother glass sheets can’t be shipped long distances, not even from Kentucky.

This limitation suggests why Foxconn scaled back from building the largest possible fab to a smaller one in June 2018 – they had to get to a size where they could ship the glass in.

The second problem is that Foxconn needed a pretty specialized workforce to set up and run such a fab. There was some controversy about importing those Asian workers late in 2018, but frankly, those types of industrial engineering or manufacturing skills are not common in the U.S.

All the other significant LCD fabs in the world are located in two time zones in East Asia — there is nothing of the kind in the U.S. Additionally, all of the production tools will come from Japan, and the people who know how to install and use them are all in those same two time zones.

The third problem is the boom and bust cycle in the LCD display industry. When times are good, many firms go out and build new fabs or add to their capacity. It takes a year or more to get that factory built and running productively (and it’s amazing how fast they do this in China). But when all those new fabs come on stream, they create a glut in the market of LCD panels. Prices fall, every producer has trouble making money, and nobody wants to invest. Of course, demand eventually absorbs all that capacity, prices rise, and everybody renews their enthusiasm to invest.

This is a well-known phenomenon. It happens in semiconductors, ocean shipping, petrochemicals and any industry where there is a long investment cycle required to bring on new capacity.

John Matthews, a professor in management at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, wrote a 2005 paper in California Management Review that dubbed this the “crystal cycle” for the LCD display industry. A lot of new manufacturing capacity for LCDs has come on stream lately, just in time to meet slowing demand. Add to that challenges facing key customers like Apple, a looming trade war that is creating a very uncertain environment, and this could be a terrible time to build a new factory.

What might explain what is happening with Foxconn’s Wisconsin plans?

In China, there is a term for this type of project: u9ad8u8bbfu9879u76ee (“Gu0101o Fu01ceng Xiàngmu00f9”) or a “state visit project,” which is signed during a high-level visit. They are announced during the visit of a head of state, or some high-profile event where there is an important political end.

When Foxconn CEO Terry Gou and President Donald Trump came to Mount Pleasant for the groundbreaking in June 2018, they both achieved political ends. Trump was making good on his promise to bring manufacturing and manufacturing jobs back to America. What better way to do it then with a high profile, high tech product like LCD displays? Moreover, for Foxconn and Gou, there are likely significant benefits from being friends with the President of the United States, and being supportive of his agenda.

In business relationships in China, this type of thing happens all the time. It might be the groundbreaking for a local factory, or it might be a big commercial deal. Back in 2015, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited the Boeing widebody facility in Everett, Washington, and announced an order for 300 aircraft. This gave Xi the opportunity to emphasize the importance of China to Boeing, its workers, suppliers and the communities they operate in — the specific details would be worked out later.

Here an important difference arises between the U.S. view of how these things play out versus the Chinese view.

In China, many deals or projects eventually go through, but often the details change, sometimes substantially. Companies figure out what makes economic sense, and if they can’t figure it out, they don’t go forward.

In the U.S., the view leans more towards “holding their feet to the fire” and making sure the party who got the subsidies delivers on what they promised to do. That’s not to say in China companies don’t forfeit their subsidies or constantly renegotiate, but in the end they try to shape the project into something that makes economic sense, otherwise they don’t go forward.

It seems possible that this adjustment was what Foxconn was trying to do – shift the project to a sounder economic footing – until the conversation between Trump and Guo. The president may have been pretty persuasive.

In the end, building a project in Mount Pleasant that is not sustainable will not benefit Foxconn, nor would it benefit the people of Wisconsin. The company has to figure out how to make the economics work, or it won’t be good for anybody. That means Wisconsin probably hasn’t heard the last words about Foxconn’s plans.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us