For Immigrants In Wisconsin Who Face Deportation, Legal Representation Is Decisive

Among immigrants living in Wisconsin whose cases began between 2010 and 2015, those who had lawyers were more than six times as likely to be allowed to stay in the country as those who didn't have representation.

May 19, 2019

Marigeli Roman and Erick Gamboa in living room in Milwaukee

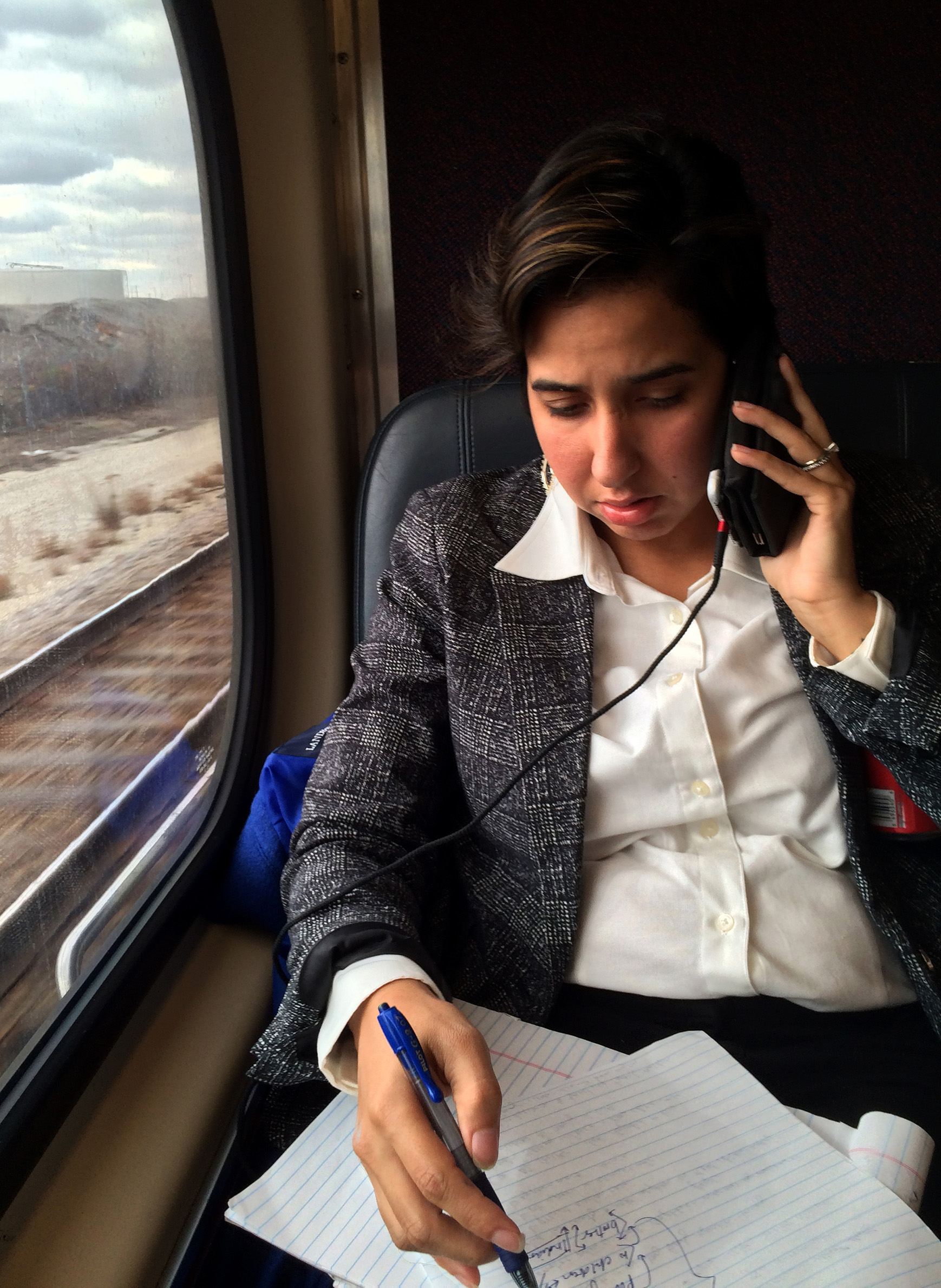

It was nearly three hours before sunrise on a frigid October morning when immigration attorney Aissa Olivarez climbed into her Honda CR-V and left her Madison apartment.

She drove an hour and 40 minutes to Elgin, Illinois, and got on the commuter train, arriving before 9 a.m. at the Chicago Immigration Court — the designated court for the roughly 300 people held in immigration detention in Wisconsin.

Olivarez travels to the Chicago court as often as a couple of times a week. She is one of just two immigration attorneys in Dane County who represent detained clients for free, part of a national pilot program that aims to provide free lawyers to immigrants.

This client, a Latin American who has been in the United States for 18 years and whose children are all U.S. citizens, had five drunken-driving arrests on his record. She knew that did not bode well for his chances of being released on bond. Olivarez told the client’s family to prepare for the worst.

In a way, though, Olivarez’s client had an advantage. In 2018, about two-thirds of immigrants who were held in detention ahead of their deportation hearings did not have lawyers, making them more likely to remain in detention and, ultimately, be removed from the United States, according to a Wisconsin Watch analysis.

Analyzing data compiled by Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, or TRAC, Wisconsin Watch found that of Wisconsin residents whose cases began between 2010 and 2015, those who had lawyers were more than six times as likely to be allowed to stay in the country as those without. Nearly 55% of those with lawyers were allowed to stay compared to 9% of immigrants without lawyers.

Nationally, the picture is similar: Immigrants without lawyers had an average success rate of less than 8%. Cases that began since 2015 were omitted from the analysis because so many of them have not yet been decided.

Olivarez works for the Community Immigration Law Center, a partially taxpayer-funded program based in Madison that provides free and low-cost legal services to some of Wisconsin’s detained immigrants.

These are people who cook at restaurants, take care of dairy cows, clean office buildings, landscape yards and put shingles on roofs, among many other jobs. They may have committed a crime — ranging from heinous to minor — or no crime besides entering the United States illegally, an offense that can bring a small fine or up to six months in jail.

Dane County is one of 13 jurisdictions around the country chosen for a new program that aims to give detained immigrants access to an attorney. Individuals facing deportation have a right to legal representation — but only if they can afford it. On average, about half of immigrants nationwide do not have lawyers. In Wisconsin, the figure is 42%.

At the hearing, Olivarez’s client appeared by video from jail on a large screen in the courtroom as the immigration judge decided whether to release him on bond. He was ordered to be detained until his deportation hearing in January. At that hearing, his application for relief based on the likelihood of facing danger in his home country was denied. Olivarez is appealing that decision.

More than 1 million immigrants and asylum seekers are facing deportation nationwide, including 3,700 people from Wisconsin.

Since President Donald Trump took office, the immigration court’s “active backlog” has grown by nearly 50%, reaching a record high of 869,013 as of March, according to TRAC data.

The backlog was fueled by the decision by then-U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions to move 330,211 cases previously closed by judges back to the immigration courts’ roll of pending cases.

Lawyers increase odds of staying

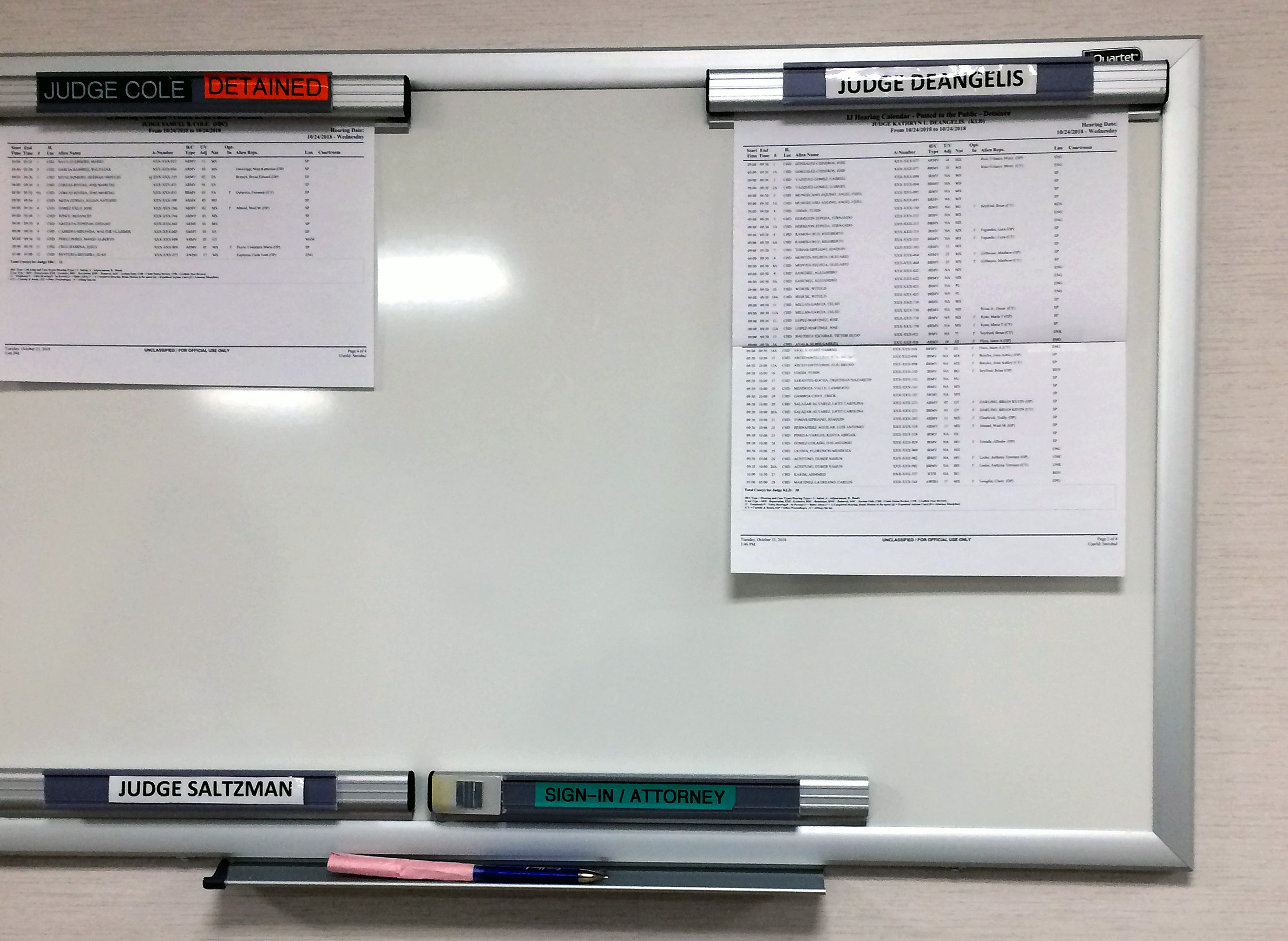

Immigration and Customs Enforcement detains immigrants at two Wisconsin facilities housed within the Dodge County Detention Facility in Juneau and Kenosha County Detention Center in Kenosha. ICE also is looking to add another facility within 100 miles of its field office in Fort Snelling, Minnesota.

Immigration attorney Aissa Olivarez said the majority of the immigrants detained at Dodge, the facility she typically serves, are undocumented people who were not apprehended by Border Patrol. Others overstayed visas or had green cards allowing them to live and work in the United States but were convicted of crimes that could make them deportable.

In December, Olivarez estimated that about one-third of the detainees at Dodge entered the country legally as asylum seekers, but their claims had not yet been decided. The flow of asylum seekers to Dodge has since slowed, as a recently enacted policy now requires most asylum seekers from south of the border to remain in Mexico while they complete the process.

In some cases, ICE picks up immigrants from local jails after they have been arrested on criminal charges. Others with prior immigration or criminal records are arrested in the “community” — meaning their homes, at workplaces or even courthouses.

Olivarez said the Trump administration has changed its enforcement priorities to include undocumented immigrants who have been charged but not yet convicted of a crime. “We do see people who are being removed from this country before they have the chance to respond to a pending criminal case,” Olivarez said.

In response, Milwaukee County Sheriff Earnell Lucas has announced that he will no longer alert federal officials of the immigration status of people in the county jail, stating that “it’s the right thing to do.”

The Daily Beast reported in March 2019 that the number of immigrants in federal detention had ballooned to an all-time high of 50,049. In some cases, that detention can last for years. A study in 2018 found 58% of detainees had no criminal convictions.

The rest of the million or so people awaiting immigration proceedings who are arrested and then released can live legally and also work — legally or otherwise — for years.

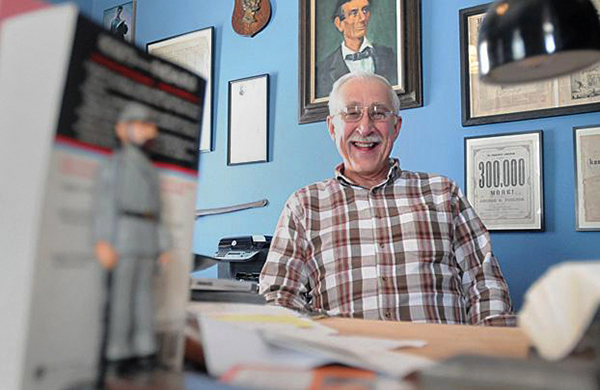

“People think that there’s legals and illegals, and if you’re illegal, they’ve got your name on some list, and when they come for you, you’re getting deported, and that’s it,” said Grant Sovern, the president of the board of the Community Immigration Law Center where Olivarez works.

Sovern said it is not that simple; immigrants have the right to challenge deportation in court. Data show that one factor can make the biggest difference: getting a lawyer.

He said his program uses “the laws that Congress passed that give immigrants the opportunity to defend themselves against deportation that they would have no idea about if they didn’t have a lawyer.”

Detention ‘life-changing’

Getting released back into the community reunites the family and allows breadwinners to continue working. It also makes it easier to get a lawyer, increasing a person’s chances of getting to stay in the country.

But for immigrants in detention, finding and paying for a lawyer is not easy. This is one of the many ways that detention puts immigrants at a disadvantage.

Marigeli Roman’s husband, Erick Gamboa, was arrested in a September 2018 immigration enforcement surge in which 83 people, most of them from Mexico, were arrested in 14 Wisconsin counties. About two years earlier, Gamboa had been arrested — he had driven his boss’ car for work and did not know that its license plates were suspended. He was fingerprinted, making it easier for ICE to locate and arrest him again later.

Lawyers told Roman that because her husband had been stopped at the U.S.-Mexico border years before, he was subject to an “expedited removal” and not eligible for a bond hearing.v

For the first two weeks, Gamboa was held at the pretrial detention facility in downtown Kenosha. During that time, he nearly gave up.

“It was a difficult time,” Gamboa said. “The fastest thing would have been to sign the deportation [paper], because it was going to be a long process. It seemed easier to get deported and try again.”

Even after Gamboa’s wife found a lawyer, he initially was not sure the odds were worth sitting in jail for weeks or months more.

“The lawyer said that I had a chance — 99 percent chance — I would lose. So I said, ‘That 1 percent is enough for me to fight,'” Gamboa said.

Gamboa ultimately won his case and was granted “withholding of removal” in December due to death threats he had received from his own father in Mexico, but he remained in jail throughout the court process. He was released in February after spending six months in detention.

Roman, who lives in Milwaukee, said her husband’s detention was “life-changing” for her and their children. The first month was especially hard.

“I didn’t want to get up, I didn’t want to eat, I didn’t want to care for my kids … I will tell you, the first month — you look at food and you’re like, ‘I don’t want to eat, because he’s not eating what I’m eating. He’s eating terrible food,'” Roman said.

Roman also faced the practical challenges of life as a single parent. Before her husband’s detention, she had been a stay-at-home mom to their three children. In her husband’s absence, she had to find a job and arrange for someone to help take the kids to school. Her mom took care of her 2-year-old.

“It moves your world in so many ways, like emotionally, mentally, physically, financially,” said Roman, who is currently protected from deportation under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy, which grants some rights to eligible immigrants who came to the United States as children.

Children ‘traumatized’ when parents taken

Aissa Olivarez said clients and their families often “deteriorate” when they are in detention. She recalled one man whose family developed medical problems during his months-long detention. His release changed everything.

“They just looked like a completely different family. They looked happy. They looked healthy,” she said.

Fabiola Hamdan has seen the impact too. She works as the immigration affairs specialist for Dane County, a position created after Trump was elected.

Hamdan said the psychological effects of detention can be severe. The sudden detention and then absence of a parent can “traumatize’ children, she said.

When Gamboa was detained, his family made the 40-mile trip from Milwaukee to the Kenosha County Detention Center for 30-minute weekly visits, where they talked on the phone with Gamboa on the other side of a plexiglass window.

Roman said she saw a change in her children, all U.S. citizens, during those months. He was the one who did homework with them and took them to soccer practice.

“It made them not want to continue playing … They didn’t want to continue life. My oldest one — he had suicidal thoughts.” That child is 10 years old.

Release helps keep family bond

Fabiola Hamdan worked with a mother of four whose husband, a green card holder, was detained for five months following a criminal conviction that the government argued made him deportable. During his detention, Hamdan said, the woman gave birth but had to continue working to pay the bills.

“It’s very heartbreaking,” Hamdan said. “Instead of enjoying the baby, right now she’s really trying to put food on the table, get some donations from churches or different places to assist their needs.”

Hamdan helped the family using a county fund for rent, utilities, diapers and food. She also connected them with Aissa Olivarez, who eventually won the case by successfully arguing that the type of crime — which Olivarez declined to reveal — did not make him deportable.

The government is appealing that ruling, but the husband has been released. Without that help, Hamdan said, the family would likely have lost its home.

“It’s like a snowball,” Hamdan said, explaining that eviction can lead to to homelessness, job loss and sometimes unsafe conditions for children. “We would be talking about a very different outcome.”

Those who are granted bond face a second challenge — paying for it. Immigration bonds must be paid in full, in cash. Nationally, the median immigration bond in 2018 was $7,500, yet, according to TRAC, can exceed $25,000.

At the Chicago Immigration Court, the median bond in 2018 was $5,000.

Erin Barbato, the director of the Immigrant Justice Clinic at the University of Wisconsin Law School, said much higher bonds are not uncommon.

“When you get a bond that is $20,000 for a family whose breadwinner is in detention, how are you going to pay that?” Barbato said. “A normal family, regardless of how much money — you don’t have an extra $20,000 sitting around.”

Some immigrants raise money online or turn to immigration bond companies, often paying hundreds of dollars each month to the companies for GPS monitoring to secure the bond. The Madison Community Foundation’s Immigrant Assistance Fund is among several around the country that help immigrants pay their bonds.

Pretrial release improves chance to stay

Once detainees are released, their cases transfer to a “released court” closest to their home — and those dockets are packed with a million-plus backlog of cases. Being allowed to remain free awaiting immigration proceedings also increases the chances of avoiding deportation, the analysis showed.

Critics argue immigrants who are released while their cases are pending will fail to return for their court hearings.

“The fact is that when these people are turned loose, they are given court dates … and a lot of them never show up. They just completely disappear into our society,” said Dave Gorak, executive director of the Midwest Coalition to Reduce Immigration, citing an analysis by the Center for Immigration Studies, which favors low immigration.

“Why should anybody report to an immigration judge when they know that the odds of them being tracked down are slim to none?” Gorak asked.

Those data show that between 1996 and 2015, about 37% of released immigrants did not show up. That means most immigrants actually did return to court. In 2017, the most recent year for which the data are available, the no-show rate was 41%, meaning 59% of immigrants did return to court.

Court attendance rates were significantly higher for immigrants who were enrolled in a supervision program, which consisted of GPS monitoring and regular in-person or telephone check-ins with a government contractor.

Ninety-five percent of immigrants enrolled in ICE’s Alternatives to Detention program showed up to their final immigration hearings, according to an analysis by the Government Accountability Office of data from fiscal year 2011 to 2013. The GAO estimates the cost of such supervision to be around $21 per participant per day — less than one-seventh of the estimated $158 daily cost of detaining an immigrant.

Going it alone rarely works

On the commuter train back from her Chicago hearing, Aissa Olivarez’s phone rings. A familiar robotic voice says she has a call from an inmate at Dodge County Jail. It is the girlfriend of one of her clients.

Olivarez, whose caseload was already full, was not able to represent the woman. She called to say she had just taken the gamble of representing herself at her bond hearing.

But the odds are not good for those who go it alone in the courtroom.

“[You’re] up against the Department of Homeland Security, who has this big file of things that they’re… ready to throw at you, and you have no idea what’s going on,” Olivarez said.

The woman who called Olivarez had the same judge and the same “facts” as her boyfriend did — but he was released on bond, and she was not. The difference, Olivarez said, is that he had a lawyer.

Immigrants ‘begging’ for lawyers

In Dane County, there are not enough immigration lawyers willing to take on detained clients to represent everyone, said Community Immigration Law Center board president Grant Sovern, whose program is funded by private fundraising and a grant from the Vera Institute of Justice. Dane County and the city of Madison also fund the program through the Madison Community Foundation’s Immigrant Assistance Fund.

Aissa Olivarez and Erin Barbato are the only two Madison-area attorneys who routinely represent detained immigrants at no cost to the client.

“There’s a small handful of people who do [immigration law] for money, and there are two people who do it for no money,” Sovern said, adding, “You know what our biggest expense is? Sending Aissa to Chicago, sometimes two or three times a week.”

Finding a lawyer from behind bars is especially difficult. Marigeli Roman’s husband found a lawyer with help from immigrant advocacy group Voces de la Frontera. The first three lawyers told her that she would be wasting her money by fighting the case.

The fourth lawyer — Ben Crouse, who won the case — charged $3,500. Money they had been saving to buy a house instead went to his legal defense, she said.

Sovern said the system is not designed to accommodate a large number of represented defendants, and detained immigrants are not read the Miranda warning — which advises they can remain silent and have the right to an attorney. Immigrants also are urged to sign a document consenting to their deportation, according to a 2011 report from the National Immigration Law Center.

“The whole system is set up so people don’t have lawyers,” Sovern said. “The first thing they do is try and get you to sign away your rights.’

Natalie Yahr is a student in the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Collaborations by the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism with journalism students are funded in part by the Ira and Ineva Reilly Baldwin Wisconsin Idea Endowment at UW-Madison. The nonprofit Center also collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, and other news media. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us