Despite Declines, Exports Loom Large In Wisconsin's Economy

The spirit of open trade with foreign markets reflected in recent trade policies has a direct impact on the Wisconsin economy.

May 10, 2018

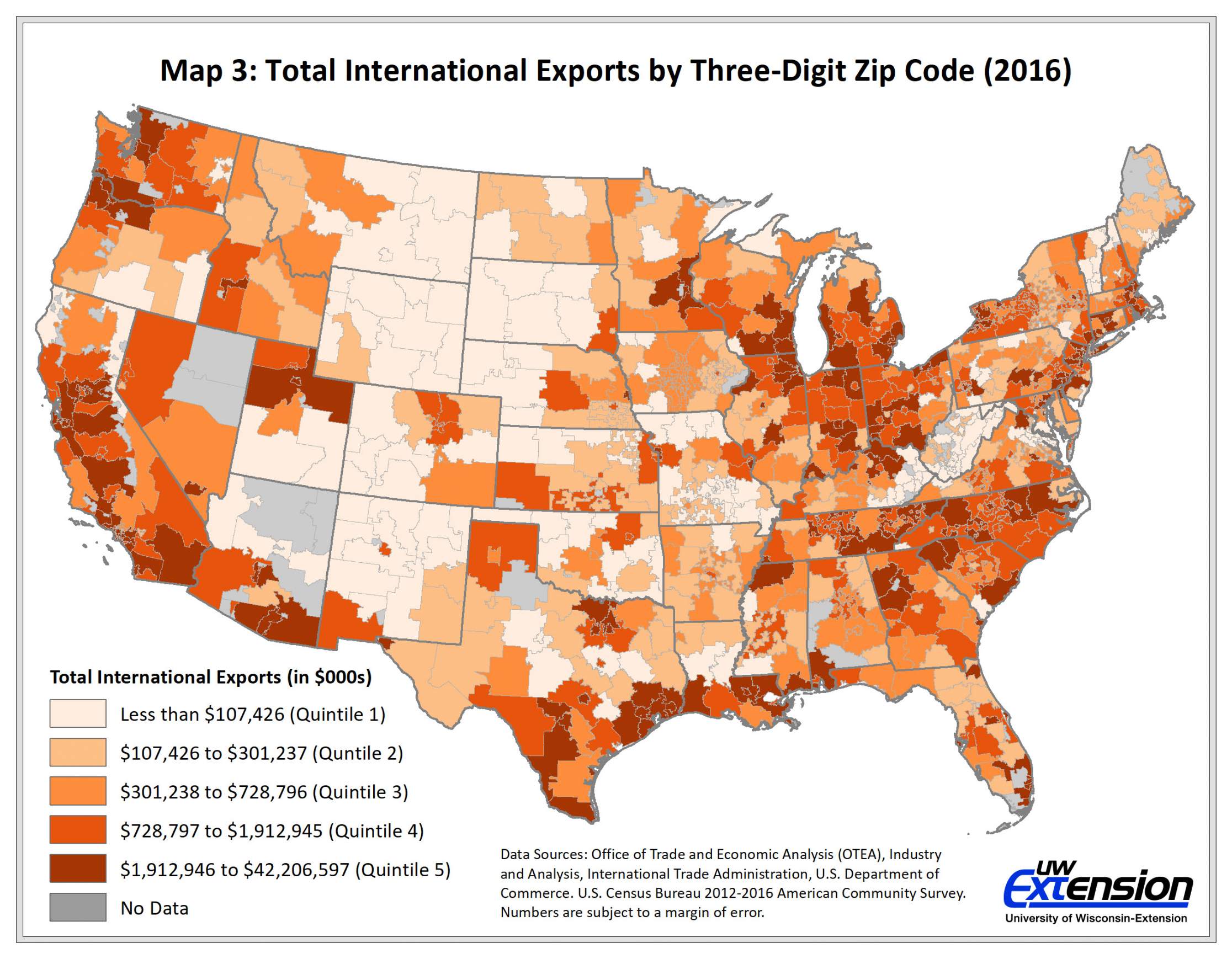

Wisconsin export markets in 2017 map illustration

The Trump administration has has signaled a strong position on United States foreign trade policy by withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, starting a renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement and the March 2018 announcement of tariffs on imported steel and aluminum.

The notion of a free trade relationship between the U.S., Canada and Mexico, was first introduced by President Ronald Reagan and signed in 1992 by President George H.W. Bush and the leaders of Mexico and Canada as the initial agreement that came to be known as NAFTA. With it, they created one of the largest zones of its kind in the world. But shifts in the global trade landscape could have an impact on that agreement and others, and cause reverberations that may affect Wisconsin’s export industries.

The head of the World Trade Organization warned about the first signs of a trade war involving the U.S. and China that could derail the global economy, as Europe kept alive a threat to join Beijing in pushing back against President Donald Trump.

“We are seeing the first movements toward” a commercial war, WTO director General Roberto Azevedo said. “It would mean a severe impact on the global economy.”

The spirit of open trade with foreign markets reflected in recent trade policies has a direct impact on the Wisconsin economy. A 2010 study from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics found that foreign exports generated about 115,000 jobs in Wisconsin, and about $10.5 billion in total income to Wisconsin households.

In 2015, the latest year of available data, 8,634 individual Wisconsin companies exported goods and services outside of the U.S. Of those, 85.9 percent were small and medium sized enterprises with fewer than 500 employees and accounted for 27.4 percent of the dollar value of exports.

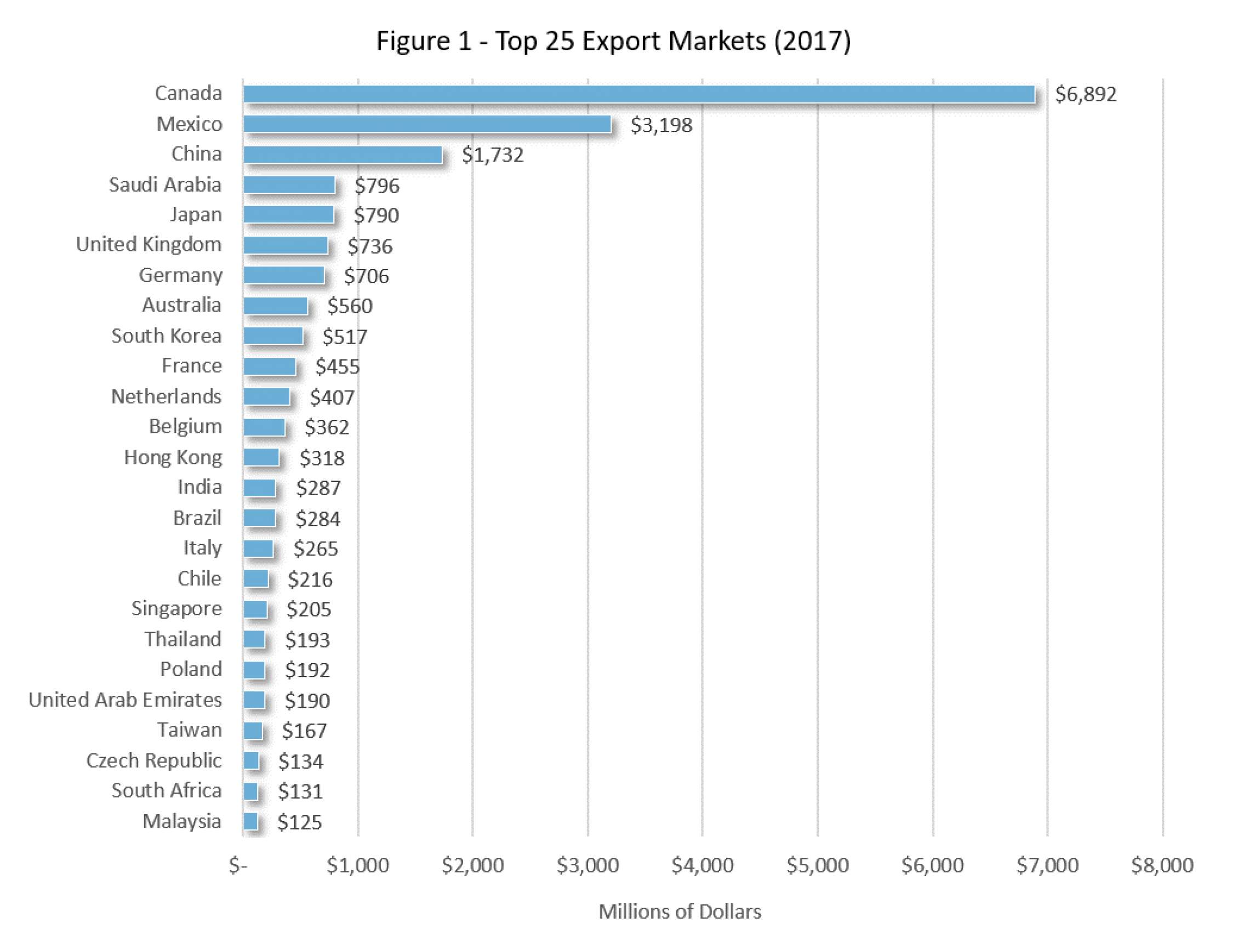

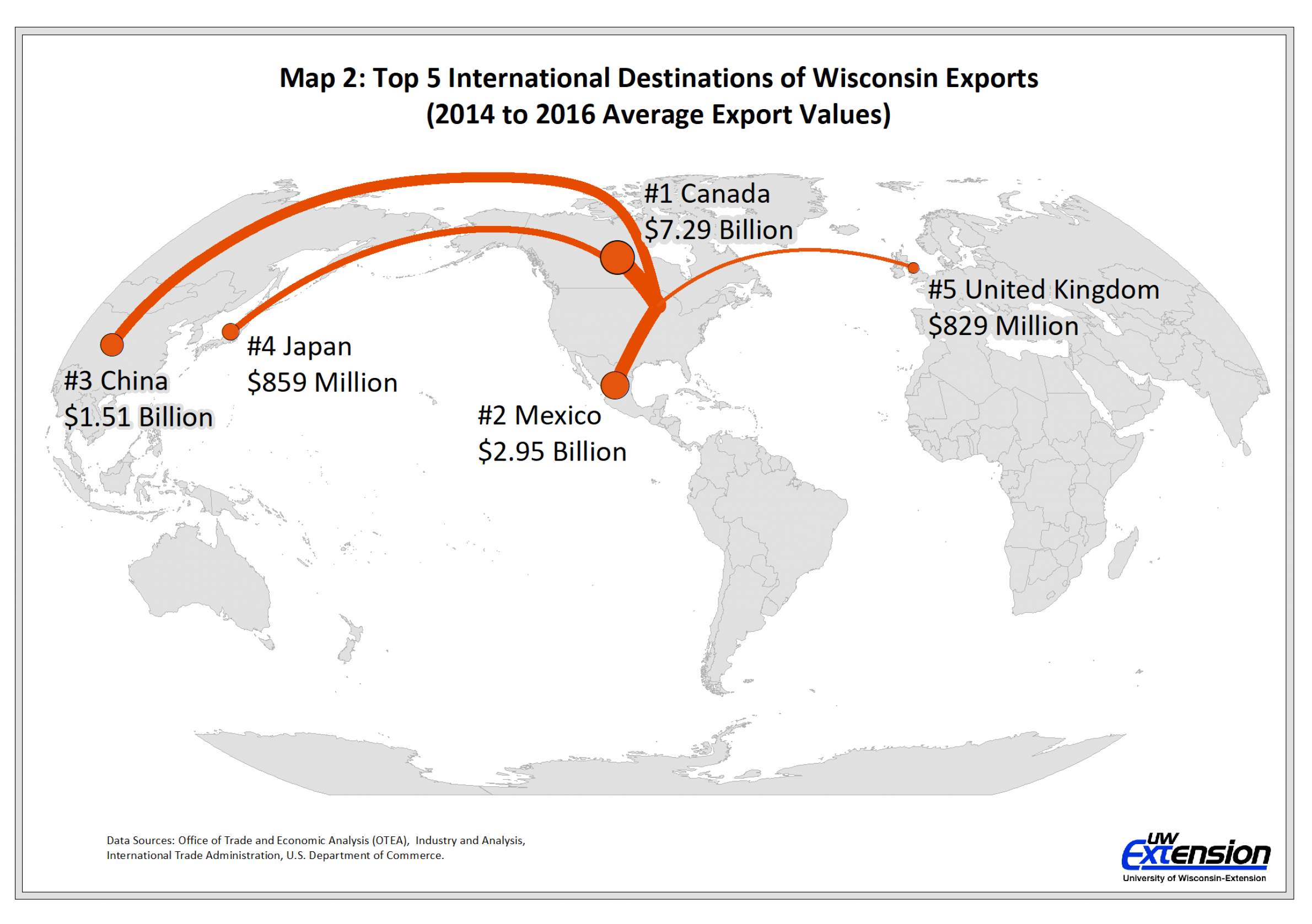

Between 2013 and 2017, Wisconsin had an average annual level of foreign exports of almost $22.4 billion, and the nation’s closest neighbors, Canada and Mexico, loomed large in that total. The biggest export market for Wisconsin is Canada, with an annual average $7.26 billion over the same period ($6.9B in 2017), followed by Mexico at $2.91 billion ($3.2B in 2017).

“…[W]alking away from NAFTA could deliver a body blow to a dairy industry that is 7.5 percent of Wisconsin’s GDP,” wrote former U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack in a November 2017 op-ed published by the Wisconsin State Journal.

As Canada and Mexico are Wisconsin’s dominant trading partners, NAFTA is particularly important to the state. As Vilsack noted, radical changes to NAFTA that restrict free trade could have a far-reaching, negative impact on the Wisconsin economy.

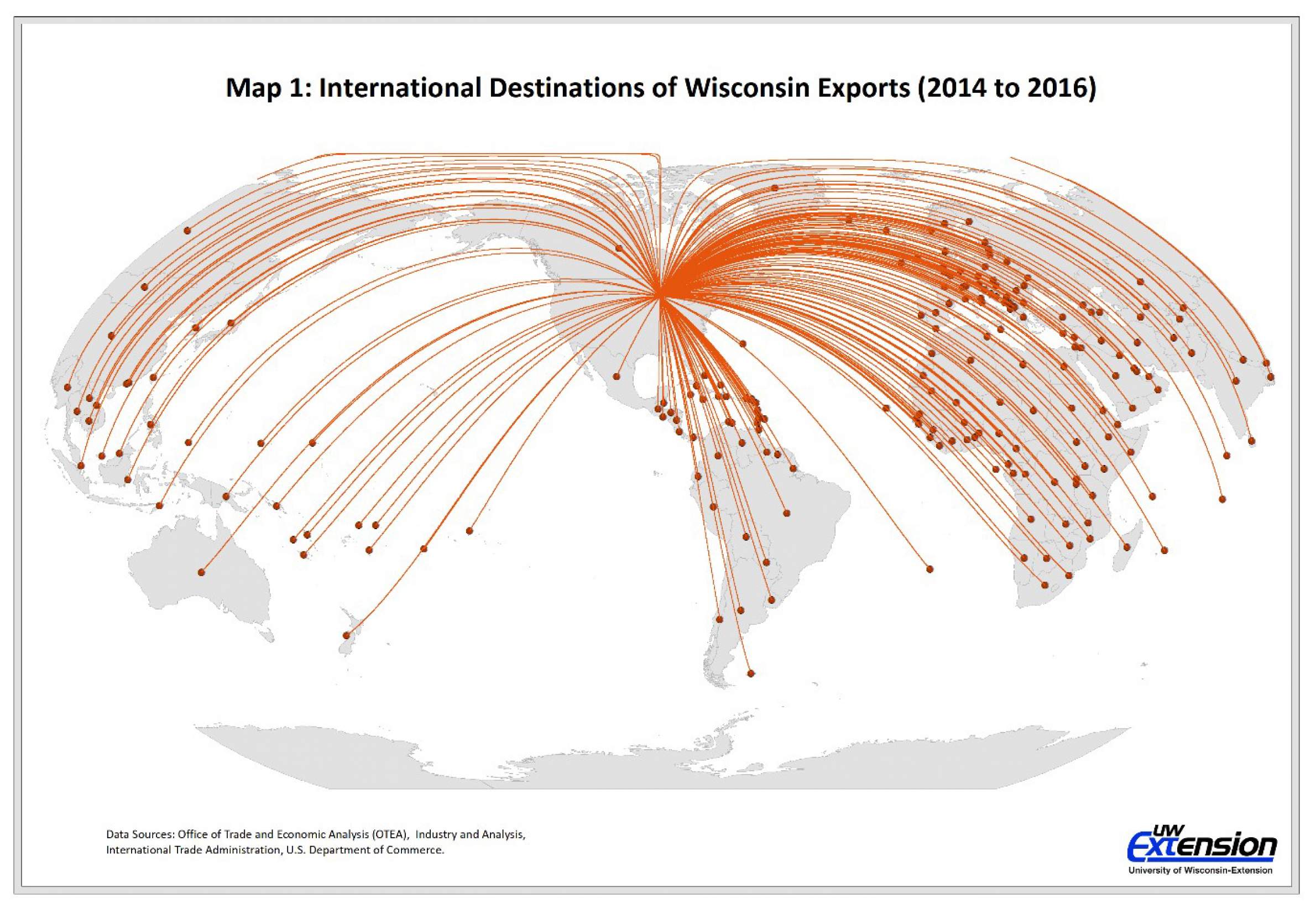

However, Wisconsin’s foreign trading partners expand beyond Canada and Mexico, including an average annual $401.6 million to the Netherlands, $257.3 million to Hong Kong, $207 million to Thailand and $178.2 million to Taiwan. Examining more detailed export data for 2014, 2015 and 2016, shows that Wisconsin exported to 217 separate countries while Canada, Mexico, China, Japan and the United Kingdom accounted for the top five destinations over the three-year period.

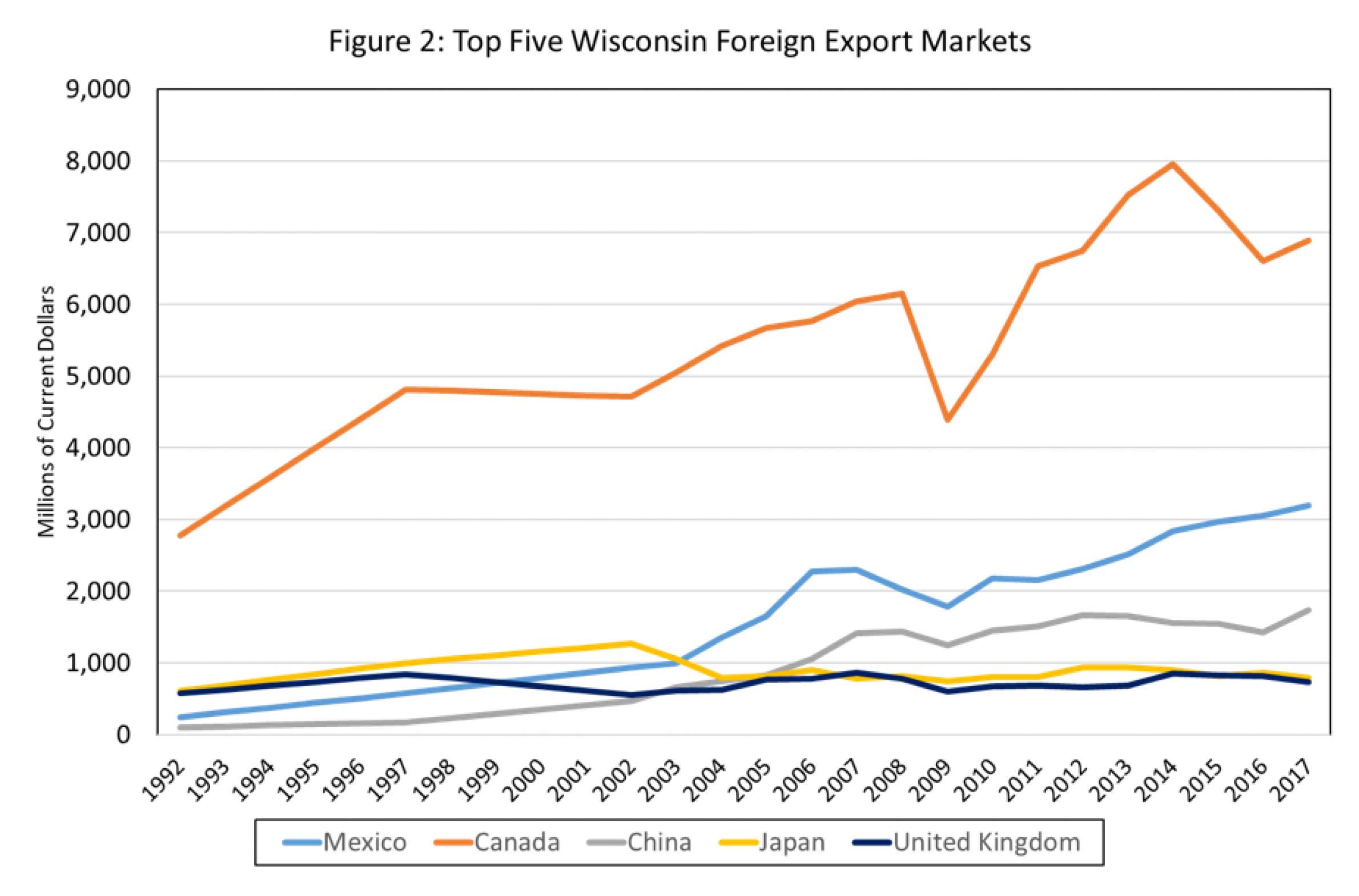

The impact of Wisconsin’s trade relationships can be observed over a longer period of time, from 1999 to 2017, as exports to the state’s major trading partners show a steady upward trend. In addition to unique changes within individual industries, the year-to-year fluctuations can be explained by general recession-driven pressures and changes in foreign exchange rates.

Specifically, if the U.S. economy is stronger than the rest of the global economy, the dollar will rise in value, making U.S. exports more expensive and thus lowering demand for them. At the same time, if the U.S. dollar is weaker, U.S. exports become cheaper thus increasing the demand for those exports. Neither Wisconsin nor the businesses that operate in the state have any control over the foreign exchange rates, or the value of the U.S. dollar.

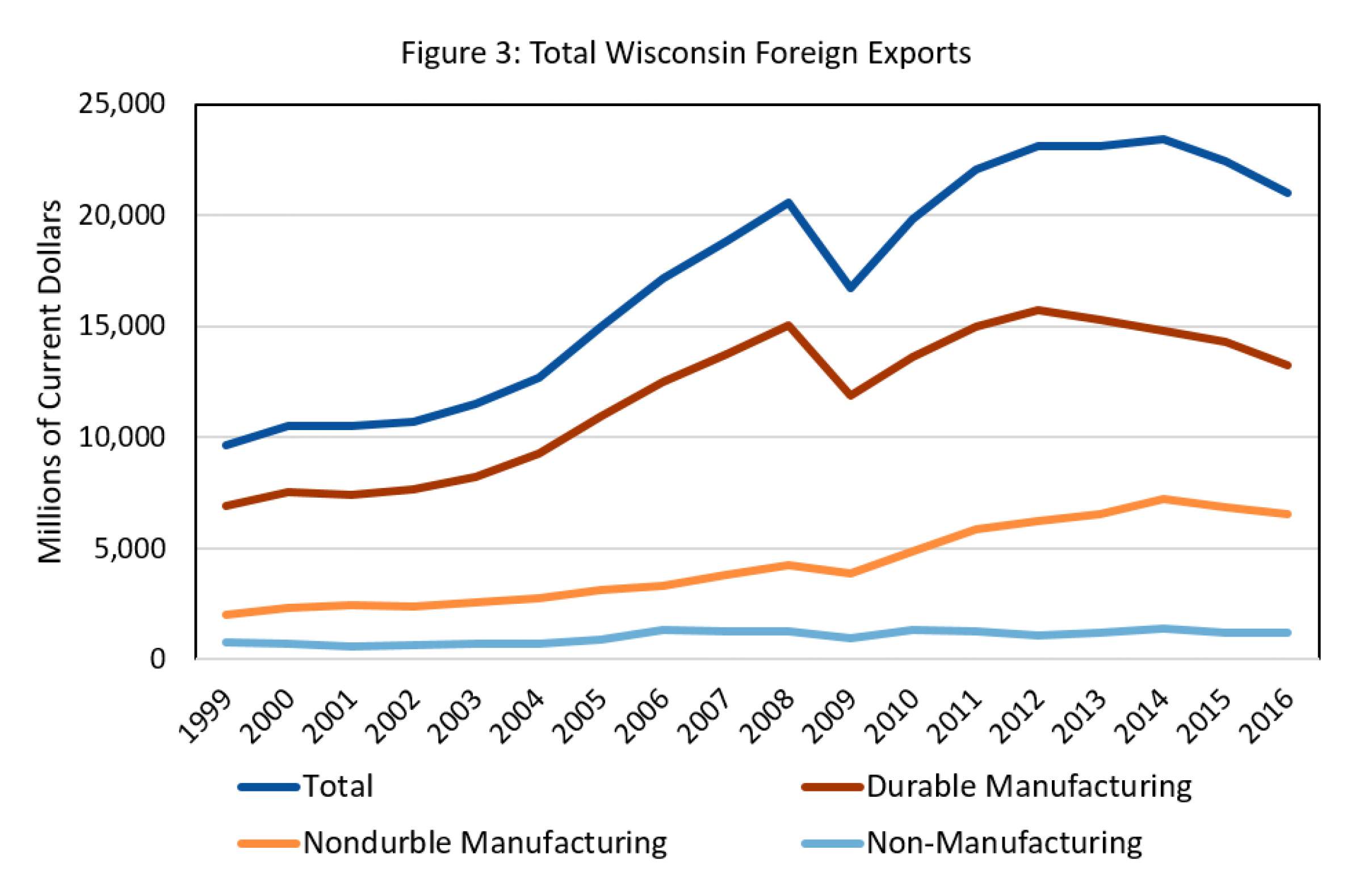

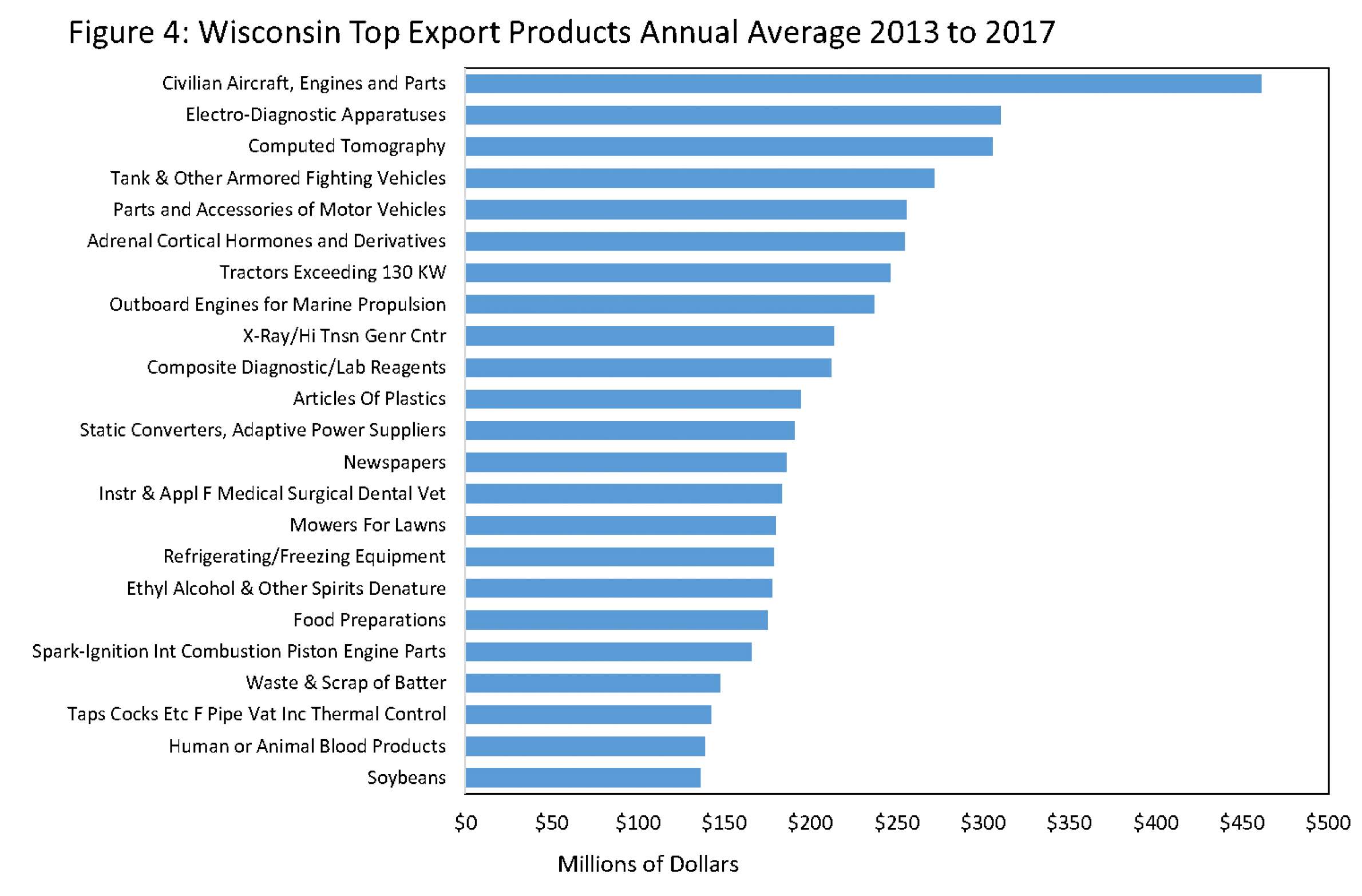

While Wisconsin exports a wide range of goods and services, the market is dominated by durable manufactured goods including such things as civilian aircraft components ($461.1 million annual average between 2013-17), electronic diagnostic equipment ($310.1 million annual average 2013-17), CT scanning equipment ($305.5 million annual average 2013-17) and soybeans ($136.2 million annual average 2013-17).

The geographic dependency of exports around Wisconsin

Despite a generally strong increase in the absolute level of exports from Wisconsin, there has been a noticeable slow-down in the 2010s, particularly in durable manufacturing. The impact of the Great Recession in 2008 and 2009 is evident in the trade data and recovery to pre-recession levels. Of the top export industries in the state, nine experienced declines between 2013 and 2017, while the remainder experienced increases.

The geographic pattern of dependency on foreign exports reveals that some parts of the U.S. and Wisconsin are more dependent than others. The reason for high levels of exports in some regions are obvious: On the West Coast, for example, the Seattle area houses Boeing, Microsoft and Amazon, the San Francisco and Silicon Valley region hosts much of the tech industry and a large volume of agricultural production is found in California’s Central Valley.

However, there are other pockets of the U.S. that are less intuitive. In Wisconsin and some of its Midwestern neighbors, the large concentration of high export levels around the southern half of the Lake Michigan region is of particular interest. Much of this area is associated with traditional manufacturing, where foreign exports are becoming increasingly important to regional economies. This “export manufacturing belt” includes much of southeastern Wisconsin.

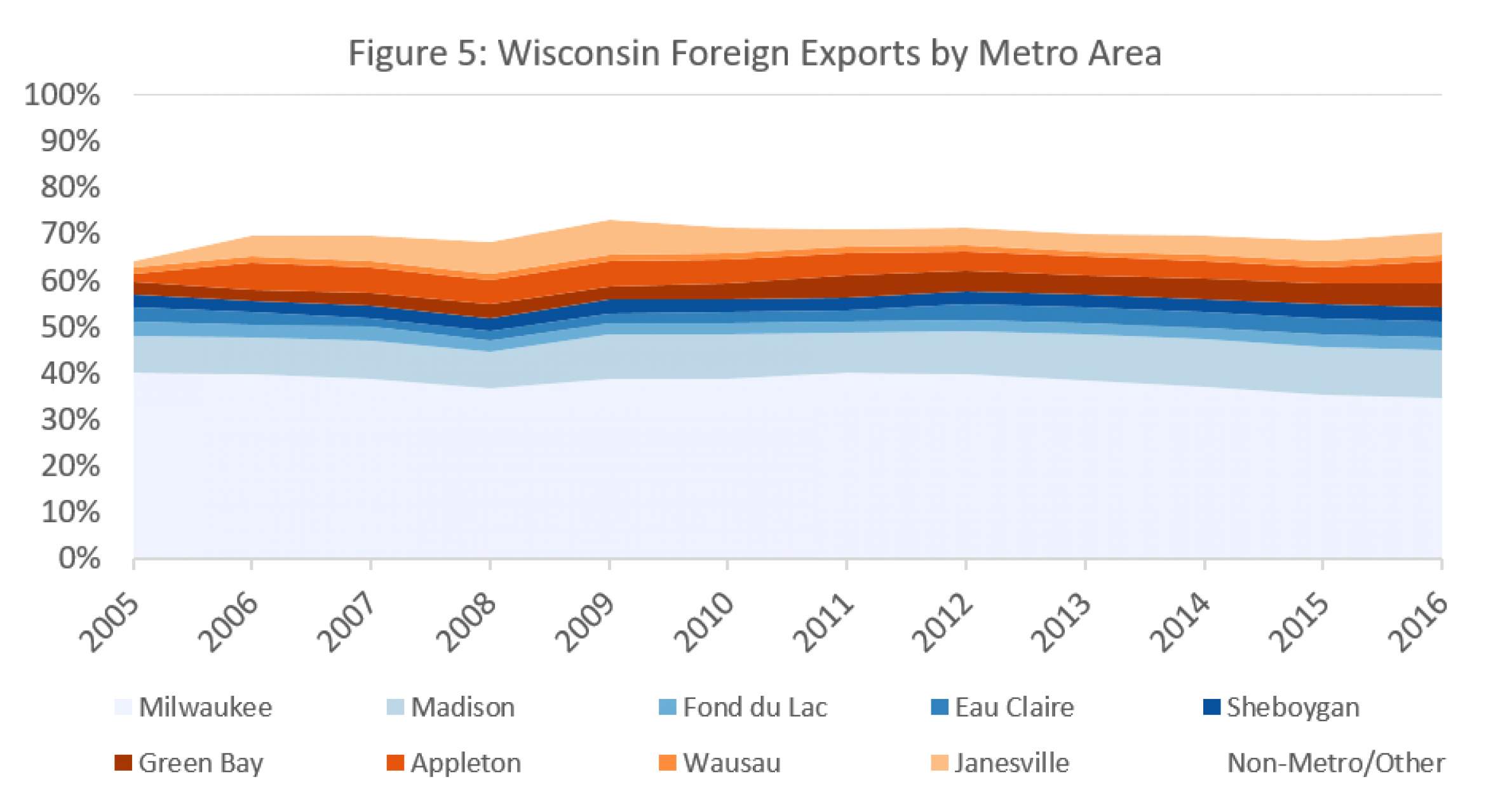

The Milwaukee metropolitan area accounted for 34.5 percent of all foreign exports from Wisconsin in 2016, the most recent year for that data, and Madison had the second largest share at 10.5 percent. Although the state’s largest city ships the largest share of goods, and the absolute dollar value of exports from the Milwaukee area increased from just over $6 billion in 2005 to $7.25 billion in 2016, the rate of increase for all of Wisconsin has been even higher. As a result, Milwaukee’s share of Wisconsin’s exports has declined in recent years, from 40.2 percent in 2005 to 34.5 percent in 2016.

In turn, other metropolitan areas across Wisconsin are assuming a larger share of the state’s export market. The Appleton area accounted for 1.8 percent of Wisconsin’s exports in 2005, but 2016 now accounts for 4.9 percent, and similar increases have been seen in the Madison, Green Bay and Janesville-Beloit regions.

Much of the decline from the peak in 2012 to 2016 can be traced to large drops in Milwaukee exports, which saw a decline of 20.9 percent, from about $9.2 billion in 2012 to $7.25 billion in 2016. Although Madison, Sheboygan, Appleton and Janesville-Beloit had increases in exports over the same time period, those gains were not sufficient to offset the declines in the Milwaukee metropolitan area.

Foreign exports are important to Wisconsin, particularly in the eastern swath of the state with a higher population density and greater emphasis on manufacturing. Manufacturing, particularly durable manufacturing, accounts for the majority of exports, but the largest of these sectors falls into what might be called specialized manufacturing, such as the aforementioned aircraft parts and medical equipment. Agriculture is also an important part of Wisconsin’s foreign exports, including prepared or processed foods, soybeans and animal furs. While it is not unexpected that the Great Recession would have a negative impact on exports, the more recent declines, particularly from the Milwaukee region, are less expected.

Although all public policy related to U.S. trade requires constant review and revision to remain sound as conditions change, rapid and drastic changes, such as the imposition of tariffs warrant scrutiny. In order to fully understand the potential impacts the trade policy changes being discussed may have on Wisconsin, one must possess a better understanding of how trade affects the state.

Steven Deller is a community development specialist at the center and a professor in the University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Applied & Agriculture Economics. Tessa Conroy is an economic development specialist at the University of Wisconsin-Extension Center for Community and Economic Development and an assistant professor in the UW-Madison Department of Applied & Agricultural Economics. Matthew Kures is a community development specialist at the UW-Extension Center for Community and Economic Development. This item was originally published as part of the UW-Extension Center for Community and Economic Development’s WIndicators reports.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us