Dead Cows Are Changing The Way Wolves Eat

It's not an undertaking that most people must think about in everyday life, but dealing with cow carcasses is serious and oftentimes strenuous business.

May 21, 2018

Gray wolf at Seney National Wildlife Refuge in Michigan

It’s not an undertaking that most people must think about in everyday life, but dealing with cow carcasses is serious and oftentimes strenuous business. Properly disposing just one 2,000 pound dead cow isn’t easy, and many dairy farmers and ranchers routinely dump livestock carcasses rather than burying or rendering them, despite laws requiring otherwise. However, research is suggesting this practice can have a meaningful effect on how predators, specifically wolves, interact with livestock, people and ecosystems as a whole.

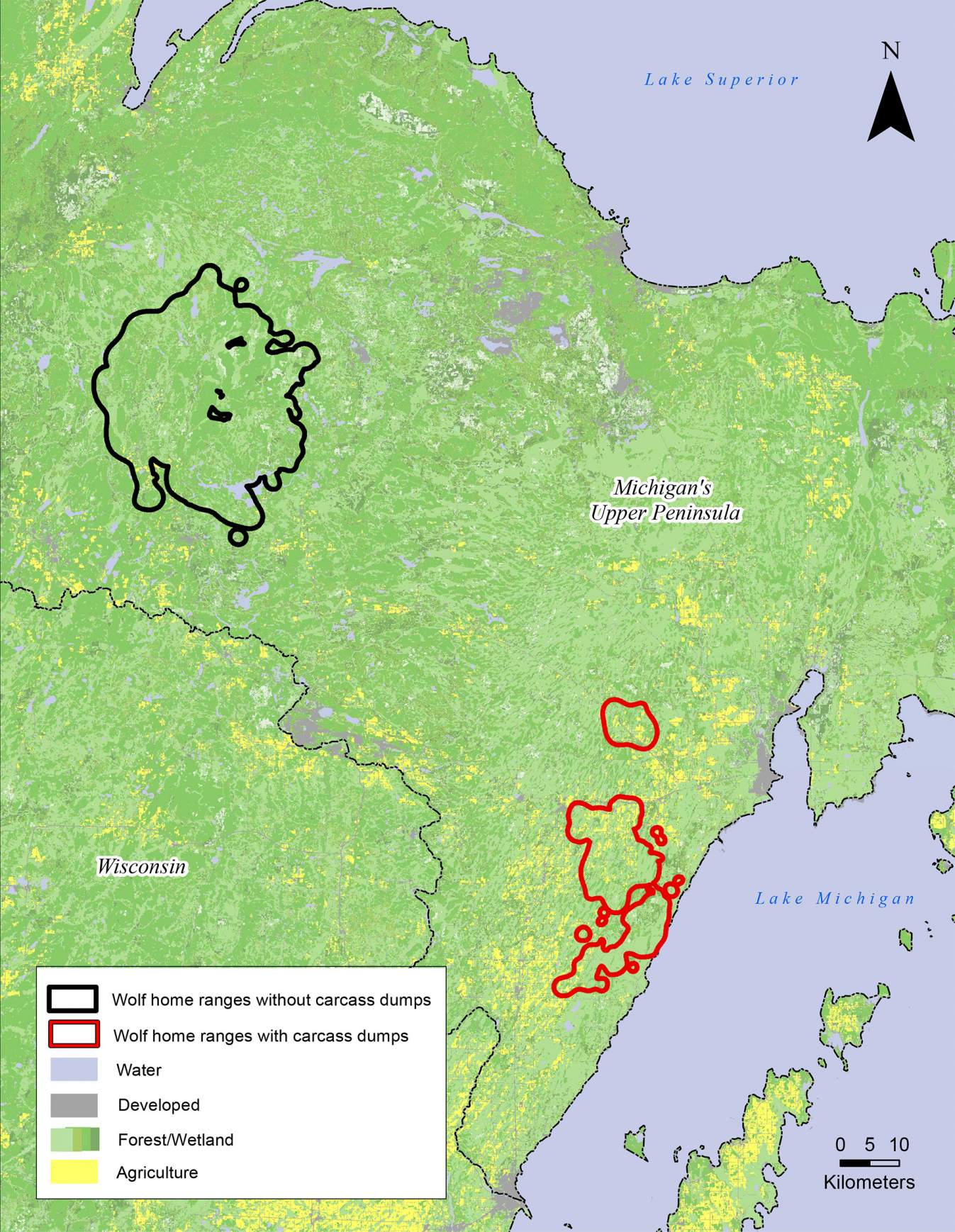

A study led by Tyler Petroelje, a wildlife researcher and doctoral candidate at Mississippi State University, tracked the feeding behaviors of eight wolves from two packs in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. This research was part of a broader predator-prey study that investigated a variety of factors that affect deer populations in the region. As reported by Great Lakes Echo, the study suggested that dumping cow carcasses alters wolf behavior.

In the North Woods of Wisconsin and Michigan, a wolf’s natural diet typically consists of deer and beaver, Petroelje explained. But he found that nearly one-third of the diet of the wolves studied consisted of cattle carcasses from dump sites on nearby farms.

Ideally, a wolf’s diet shouldn’t contain any livestock. However, depredation rates did not rise in the area that was studied, located in the southern Upper Peninsula across the Menominee River from Wisconsin. In other words, while wolves were spending more time near these farms, they weren’t killing any livestock.

Petroelje found that wolves were feeding at carcass dump sites, which are illegal in Michigan, by using GPS tracking collars. By this means, he was able to follow the finescale movements of the collared wolves, ultimately tracking more than 80,000 locations. With this information, Petroelje found that wolves who ate at dump sites preyed less on their usual quarry. The predators also tended to be less active and not travel as far to hunt. Petroelje said this dynamic is similar to way bears eat from bird feeders in yards.

In Wisconsin, the issue of improper carcass disposal isn’t widespread, explained Scott Walter, a large carnivore specialist at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, though that’s not to say that it doesn’t happen. Walter said the DNR works with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services office to educate livestock owners in the northern Wisconsin region on the importance of proper carcass disposal; the federal agency also helps investigate when depredations occur. The DNR has also hosted workshops with livestock owners to educate them on the best legal means to get rid of carcasses.

According to Wisconsin law (95.50(3)), livestock carcasses may not be exposed to access by dogs or wild animal for more than 24 hours in April through November and no longer than 48 hours from December through March. The Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection, which is responsible for regulating these practices, recommends rendering as the best way to dispose of livestock carcasses, as it poses the least threat compared to burying or burning remains, which can cause biosecurity hazards. But as Petroelje noted, and DATCP underscored, the process of rendering is difficult and expensive, which often dissuades farmers and ranchers from doing it.

Furthermore, Petroelje explained that many farmers are simply unaware of law.

One livestock owner Petroelje met while conducting the research said they noticed an increase of wolves on their land but didn’t understand why. After speaking with Petroelje and realizing the pervasiveness of the issue, the farmer started burying his carcasses.

“I think a lot of it is just education,” Petroelje said. “A lot of people are just unaware of what the law is and what the proper response is. It can be as simple as just burying the food source. Just like the same thing with bears, you take away the bird feeders and they’re going to stop coming by your house. A similar rule applies with wolves, if you take away the food source, they don’t really have a reason to be around anymore.”

Conversely, farmers and ranchers elsewhere use dump sites to lure predators away from their livestock. As Montana Public Radio reported in June 2017, ranchers in that state’s Big Hole Valley worked cooperatively with each other and alongside local, state and federal agencies to create one designated location for anyone to drop off carcasses in hopes of keeping wolves and bears off their property.

According to DATCP, there are no approved dump sites in Wisconsin, like those in Montana, since the practice is illegal in the Dairy State.

Though Petroelje only looked at nine illegal dump sites in the Upper Peninsula in use at the time of the study, he said other literature suggests that they exist across the Great Lakes region.

The practice of creating dumping sites for livestock carcasses is not new. But Petroelje noted that as the wolf population continues to grow in northern Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin, so do the risks for human and wolf interaction. This doesn’t mean that wolves are more dangerous; rather, the likelihood of interaction becomes greater.

“This practice seems to be quite pervasive, and talking with some farmers, it’s obviously been going on for quite some time,” he said. “It probably didn’t cause a problem 30 years ago, but now that wolves have returned, it’s something that we can take this observation and say ‘We do need to be aware of this, and we do need to make sure we can inform a lot of these livestock owners that they can reduce risks of wolf-human interaction by burying these carcasses and following the law.'”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us