Birch Thefts Pressure An Already Declining Resource

An ongoing rash of illegal harvesting in northern stretches of Minnesotaand Wisconsin is helping hasten the decline of the region's paper birchtrees.

April 17, 2017

Paper birch tree poaching waste in Washburn County

An ongoing rash of illegal harvesting in northern stretches of Minnesotaand Wisconsinis helping hasten the decline of the region’s paper birchtrees.

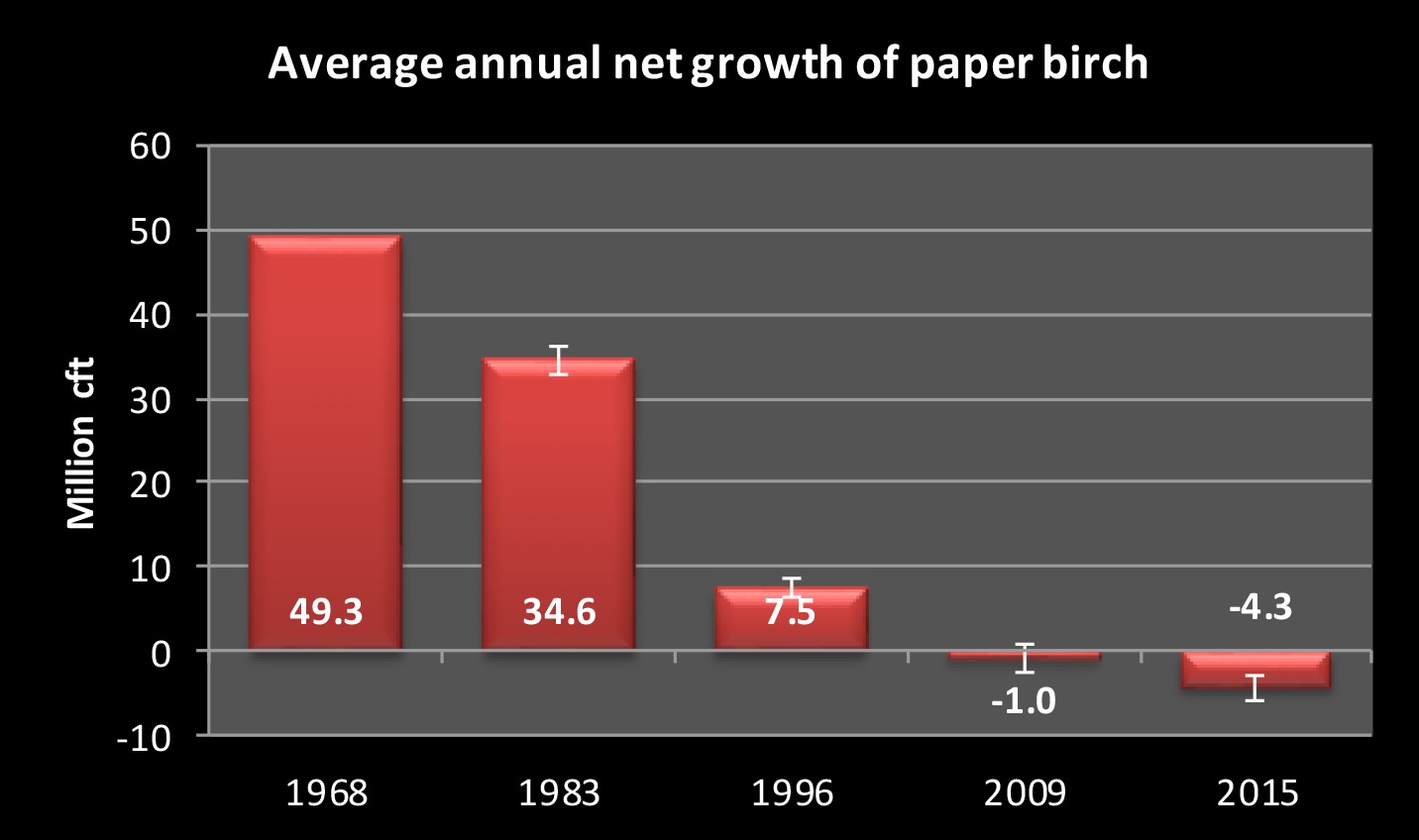

In Washburn County alone, officials sayat least 1,700 birch trees have been illegally cut since fall 2016 alone, a response to the trees’ popularity as decor. This poaching follows decades of natural and human blows to the species. The volume of birch trees in Wisconsin has decreased 54 percent since 1983, according to a 2016 report from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Division of Forestry. Now, these trees are dying faster than they are reproducing.

In a historical context, it’s an intriguing twist that human activity is putting new pressure on birch in the ever-changing North Woods, because they were once an indirect beneficiary of pervasive logging. As loggers clear-cut wide swaths of the region’s ancient pine and hemlock forests in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they left behind massive amounts of fallen trees and branches. This material, called “slash,” dried out and made the region more susceptible to forest fires. These fires harmed some tree species’ ability to reproduce, but created favorable soil conditions for birch — which, thanks to the clear-cutting, had plenty of light and room to spread.

Most of the paper birch losses have taken place since the late 90s and early 2000s, when the trees experienced about eight years of drought, many of them dying without spreading their seeds. They’ve also suffered from insects and diseases, and struggled to compete with other tree species including the aspen and red maple, said Colleen Matula, an Ashland-based forest ecologist with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. The North Woods are also seeing a lot less of those fires common more than a century ago.

“Typically birch was maintained and generated by fire, and most of that is suppressed now so foresters resort to site scarification and other measures,” Matula said. (Scarification is a process through which plant seed coats require alteration, in some cases through fire, to allow germination.) She added that climate change can aggravate some of these challenges to birch, but that the trees in Wisconsin would likely be struggling even absent its effects.

Paper birch poaching is attracting more attention, but in places like Douglas County it’s been going on for more than a decade, found Wisconsin Public Radio reporter Danielle Kaeding. In an April 6, 2017 interview on WPR’s Central Time, she noted how the poaching is contributing to the ongoing decline of the species in the region.

“If you combine the lack of birch trees with what we’re seeing right now in illegal harvesting, or illegal harvesting and efforts to grow it, it’s kind of leading to a lot of concerns about the sustainability of the resource,” she said.

The problem isn’t just in how much birch people are illegally cutting, but how they’re going about it.

Just about all the poaching has focused on younger trees, because people make decorations out of branches and slim trunks, not mature trees with a larger diameter.

“A lot of people want to have that clean young birch tree look in their homes,” Kaeding explained on Central Time.

For poachers, the sweet spot for birch are trees between 6 and 15 years old, Matula said. This age means fewer birch will grow old enough to reproduce.

“We need seed-producing trees, and that entails for the tree to get about 45 to 50 years old before it produces seed,” she said.

Birch tree trunks that have been cut down can sprout anew from stumps, but even here, the poachers’ actions are damaging. Cutting a tree lower to the ground creates the best conditions for sprouting, because it helps to stimulate hormones in the stump, Matula said. But illegal harvesters, perhaps trying to spare themselves more back pain, are cutting birch trunks higher from the ground, leaving stumps about 3 or 4 feet tall. That height is less conducive to sprouting.

These thefts also stymie the efforts northern Wisconsin environmental officials have made over the years to manage birch, as Washburn County forester Mike Peterson explained in an April 14, 2017 interview on Wisconsin Public Television’s Here And Now.

“When we harvest white birch, we make a very concerted effort to get white birch started, regenerated, and regrown before we harvest,” Peterson said. “We’ve got hundred and hundreds of hours and a lot of money invested into disturbing the soil underneath these stands so we can get white birch to regrow, and then to come back to look at some of these these sites and see that they’ve stolen all the one-inch, two-inch, three-inch-diameter material off of this, it’s bothersome, because in a lot of ways they’re stealing the future off of these young forests.”

Authorities are weighing a variety of possible solutions, from increasing forest patrols to conducting a “zoned harvest” of birch in order to improve management of the resource.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us