Bears, Wolves And People In Search Of Balance

Across wide swaths of Wisconsin, black bears and gray wolves have long played an important and prominent role in the food chain. But human activities can threaten populations of these wild animals, especially when they are considered a threat to agriculture.

November 16, 2017

Adult black bear next to tree

Healthy ecosystems need predators. Across wide swaths of Wisconsin, black bears and gray wolves have long played an important and prominent role in the food chain. But human activities can threaten populations of these wild animals, especially when they are considered a threat to agriculture. The question of how to balance the health of large predators with the needs of people has sparked fierce and intractable political debate, especially when it comes to wolves.

At one point in Wisconsin’s history, wolves were hunted clean out of the state; over recent decades, federal endangered-species protection and population management practices that didn’t just rely on killing these animals led to an increase in their population. The state opened a wolf-hunting season in 2012, though the protected status of wolves and therefore the status of the hunt were subsequently reversed, and the status of each remains contentious.

In defending the wolf hunt, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources has argued that it’s not at odds with maintaining a stable population of wolves in the state. But questions about the hunt remain at issue, including the role of public input in the DNR’s policymaking and whether culling is balanced appropriately with other management practices.

Bears are much less of a hot-button issue, perhaps because their population is much larger than that of wolves, and because bear hunting in Wisconsin has been the norm for a long time. But there was also a time when Wisconsin’s black bear population was dwindling, and these animals can still create trouble for farmers and other people whose lives overlap with their habitats.

Brad Koele, a wildlife damage biologist with the DNR, discussed some of the finer points of the state’s bear and wolf management practices in a May 21, 2016 talk at a regional cow-calf meeting at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Spooner Agricultural Research Station. The talk was recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s University Place.

Koele delved into the history of both bear and wolf populations in Wisconsin, and described what is happening with these animals in the 21st century. He made clear that he favors keeping wolves off the federal endangered species list, but discussed a variety of ways other than hunting in which state and local government officials help Wisconsinites deal with large predators.

Key facts

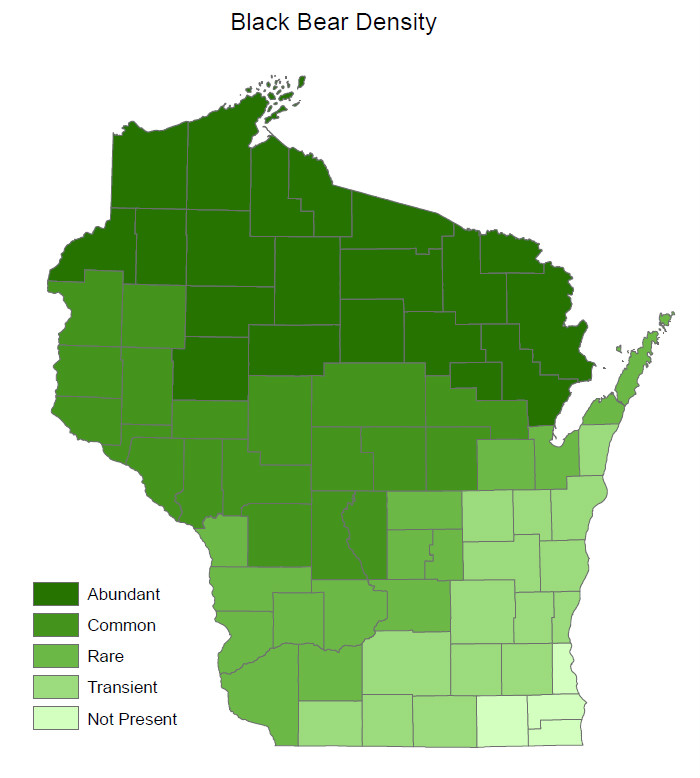

- Black bears (Ursus americanus) are most abundant in the northern third of Wisconsin, but are expanding their range into the southwestern part of the state. They are still seldom seen in southeastern Wisconsin. (The species is found in many areas of North America, and is not deemed to be threatened or endangered at the continental level.)

- Wisconsin’s bear population has grown significantly since the late 1980s. In early 2016, the state Department of Natural Resources estimated it to be about 28,650. The state’s bear population can create conflicts with humans, through damaging crops, apiaries and homes.

- The DNR maintains an active bear management program around the state and hunters must possess a license. Hunting licenses help fund the state’s bear management programs.

- Through its registration process, the DNR seeks to collect teeth from every bear harvested in a given hunting season, which provides data on whether the bear population is aging.

- The DNR also conducts an annual bear bait station survey, hanging meat from trees and tracking where bears end up grabbing it. Baits are typically placed in trees with soft wood so that animals trying to reach it leave behind distinctive claw marks, which makes it easier to determine whether a bear or another species was present.

- Another DNR monitoring effort for bears sets out bait that contains tetracycline. This antibiotic creates a marker in bears’ bones, so when a given animal is harvested, researchers can check for those markers to gather further data on the population. However, tetracycline monitoring was not conducted in 2016 due to new FDA restrictions on the use of antibiotics.

- Wisconsin primarily manages wildlife through hunting and trapping. The numbers of bears killed by hunters has increased as the population of these animals has increased. The state did not have a bear hunting season in 1985 when the population was down to about 4,500 animals. Following that year, the state created a different permit system for hunting bears and imposed limited quotas, which has helped bear numbers recover. License numbers and quotas have increased as the population has grown.

- Wisconsin bear-hunting licenses are so in-demand from residents and out-of-state hunters that wait time for receiving one can be as long as nine years, depending on the state’s bear-hunting zones.

- Farmers are eligible for reimbursement through DNR wildlife management programs if bears damage certain kinds of crops, including corn, soybeans, cranberries, orchard trees, Christmas trees, nursery stock and apiaries. Farmers who experience damage from a bear must notify a county specialist within 14 days. They also have to allow public access for bear hunting on their property. In 2015, 290 individual farmers in Wisconsin enrolled in bear-damage programs.

- The DNR’s primary method for dealing with damage by a bear is to trap the animal and relocate it at least 25 miles away, into state forests and other public lands. The state relocated 365 bears in 2016. When bears are damaging crops or apiaries, officials and farmers will often work together to put up more fencing. Agricultural damage programs do issue some shooting permits as a last resort when bears kill livestock, but the DNR prefers to keep the bears alive to keep recreational hunters happy.

- Officials handle between 800 and 1,500 complaints each year related to non-agricultural damage by bears. Called nuisance damage, it includes attacks on garbage cans, items in campgrounds and bird feeders.

- Gray wolves (Canis lupus) were hunted aggressively in Wisconsin in the first half of the 20th century, so much so that by 1960, there were none left in the state. After the passage of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, wolf populations then in northern Minnesota naturally expanded and move into northern Wisconsin. The protection status of wolves in Wisconsin has gone back and forth many times over ensuing years. (The species is found across many areas of the Northern Hemisphere, is listed as threatened or endangered in several areas of North America, and is deemedto be of “least concern” at the global level.)

- The DNR works with volunteers around Wisconsin to look for wolf tracks in the winter. The agency also tracks pack counts and sometimes uses aerial surveys to determine the number of wolves in the state. Over the winter of 2015-15, officials determined that there were between 746 and 770 wolves in Wisconsin, and at least 208 wolf packs. Most were concentrated in northern areas of the state, especially its northwest corner.

- Wisconsin’s compensation program for farmers who lose livestock to wolves was started in 1984. At the time, this program wasn’t just for wolves but also covered other endangered species, including osprey. In the 1999 state budget, the state decided that it would continue to fund programs for wolf depredations whether or not wolves were listed as an endangered species. The program provides funding to owners of livestock, pets or hunting dogs killed or injured by wolves, excepting hunting dogs attacked while actually engaged in the pursuit of wolves.

- Wolf depredations began to increase in 2005. The DNR tracks wolf depredations and issues reports about the different types of attacks on domesticated animals. It also provides detailed information on dog depredations.

- The state of Wisconsin pays out far more in compensation to farmers for deer damage than for bear or wolf damage. In 2014, deer accounted for 73 percent of compensation paid out by the state, whereas wolves accounted for 6 percent and bears 12 percent.

Key quotes

- On the popularity of Wisconsin’s bear hunt: “We’re kind of a destination state for bear hunting. Our success rates here in Wisconsin for hunting are unmatched by any other state… Our application levels have increased pretty steadily. You know, right now, around 110,000 applicants is what we receive each year.”

- On why some hunters are willing to wait a long time for a bear-hunting permit: “Historically, in the state, hunters have preferred kind of a high-quality, high-success hunt over a lot of opportunity.”

- On why bears that kill livestock are sometimes shot or trapped and euthanized: “Livestock depredation is kind of a learned behavior, and what we’ve found is typically once a bear depredates, it’s likely to depredate again. So our response, you know, for depredating bears is, in most cases is… a lethal control for that.”

- On how payments for damage claims are set: “For the standard row crops, livestock, those prices are set by the county. Typically the county damage specialist will talk with seed dealers, feed stores, UW-Extension, and they’ll come up with a price each year for those crops.”

- On popular conceptions about the DNR’s role in restoring the wolf population: “There’s a lot of misconceptions that, you know, state DNR brought wolves back in. That’s not the case. Wolves, you know, expanded and recolonized Wisconsin through those remaining packs that were in northern Minnesota and Ontario…They’ve colonized the majority of the prime wolf habitat in the northern part of the state and also in the central forest.”

- On varying wolf protections in different states: “Wisconsin, Michigan and Minnesota — it’s considered one Great Lakes population of wolves. Unfortunately, in my opinion for Wisconsin and Michigan, they’re endangered species in Wisconsin and Michigan and they’re a threatened species in Minnesota… Minnesota can still implement lethal control at depredation sites, because it’s a threatened species there, whereas Wisconsin says it’s an endangered species. We have no lethal control authority right now.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us