As 'Bell-Ringers' Pile Up, More Badgers Leave Football

UW-Madison student-athletes were diagnosed with 137 concussions from 2014 to 2018, according to records from an ongoing NCAA and U.S. Department of Defense concussion study.

December 17, 2018

Wisconsin Badgers football versus Northwestern helmet on turf illustration

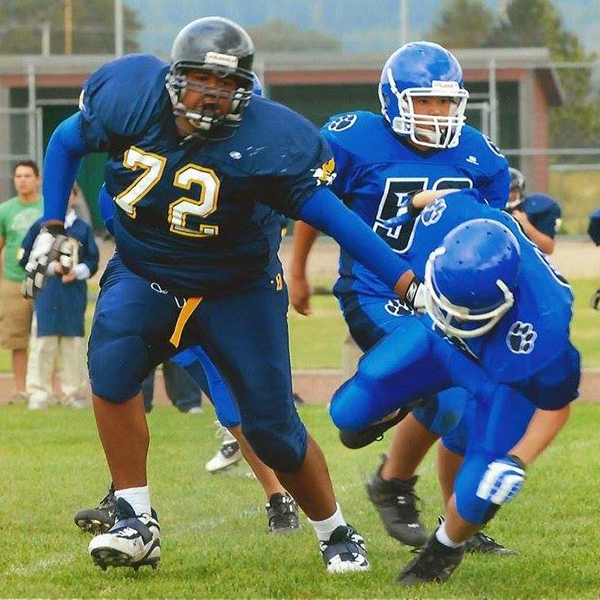

The hit that put Walker Williams’ brain over the edge — leaving him with ongoing headaches, mood swings, ringing in his ears, depression, anxiety and short-term memory problems — was nothing out of the ordinary.

The University of Wisconsin football team had the ball and was lined up against Northwestern’s defense during a November 2015 game in Camp Randall Stadium. With 13:29 left in the second quarter, the ball was snapped, and the Badgers’ offensive line sprang into motion.

The clock ticked down to 13:28, and Williams, an offensive lineman, blocked a Northwestern player from moving toward the ball carrier. Their helmets collided — something that happens all the time in football.

A second later, Williams’ mind went blank. He stayed in for the next four plays, but he is not sure why. He does not remember any of them.

When Williams came over to the sidelines, “it was quite clear that I was not okay,” he said. His “speech was off” and he “wasn’t all there,” so associate head coach Joe Rudolph took him out of the game. Williams remembers bits and pieces of the episode, such as sitting on the bench and getting evaluated in the training room.

“Those memories are kind of like old childhood memories, where you can kind of see yourself there,” Williams said. “You get the settings, but the details you don’t really get.”

It was his fifth and final concussion since he began playing in middle school. After that, he was out for the season, and in March 2016, Williams quit football entirely. Now, Williams said he experiences “detriments in all sorts of aspects of my life.” And he worries about the very real possibility that he may develop dementia because of the brain injuries he suffered on the football field.

Two of Williams’ teammates, former Badgers fullback Austin Ramesh and former outside linebacker Jake Whalen, also quit football after suffering post-concussion symptoms. Whalen, who is still a UW student, quit the team in 2017. Ramesh, who was in line for a possible contract with the NFL’s Arizona Cardinals, walked away in May.

In all, UW-Madison student-athletes were diagnosed with 137 concussions from 2014 to 2018, according to records from an ongoing NCAA and U.S. Department of Defense concussion study obtained by the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism under the state Open Records Law.

Key information — including athletes’ names, which sports they played and whether the brain injuries were sports-related — was omitted in records released by the UW. Officials cited exceptions for research, student privacy and personal health information in withholding the information.

Houston attorney Jeff Raizner, who is working on a class action lawsuit against the NCAA, said student-athletes and the public “can only benefit” from more information about brain injuries.

“For far too long, the risks and the dangers of concussions have been kept secret,” he said.

Raizner said in coming months, more athletes are expected to join the 110 former college football players who are suing the NCAA for compensation related to brain trauma. A separate lawsuit filed against the NCAA by the widow of a former player was settled in June for an undisclosed sum, and it could set the framework for future litigation, he said.

Homework hard after brain injury

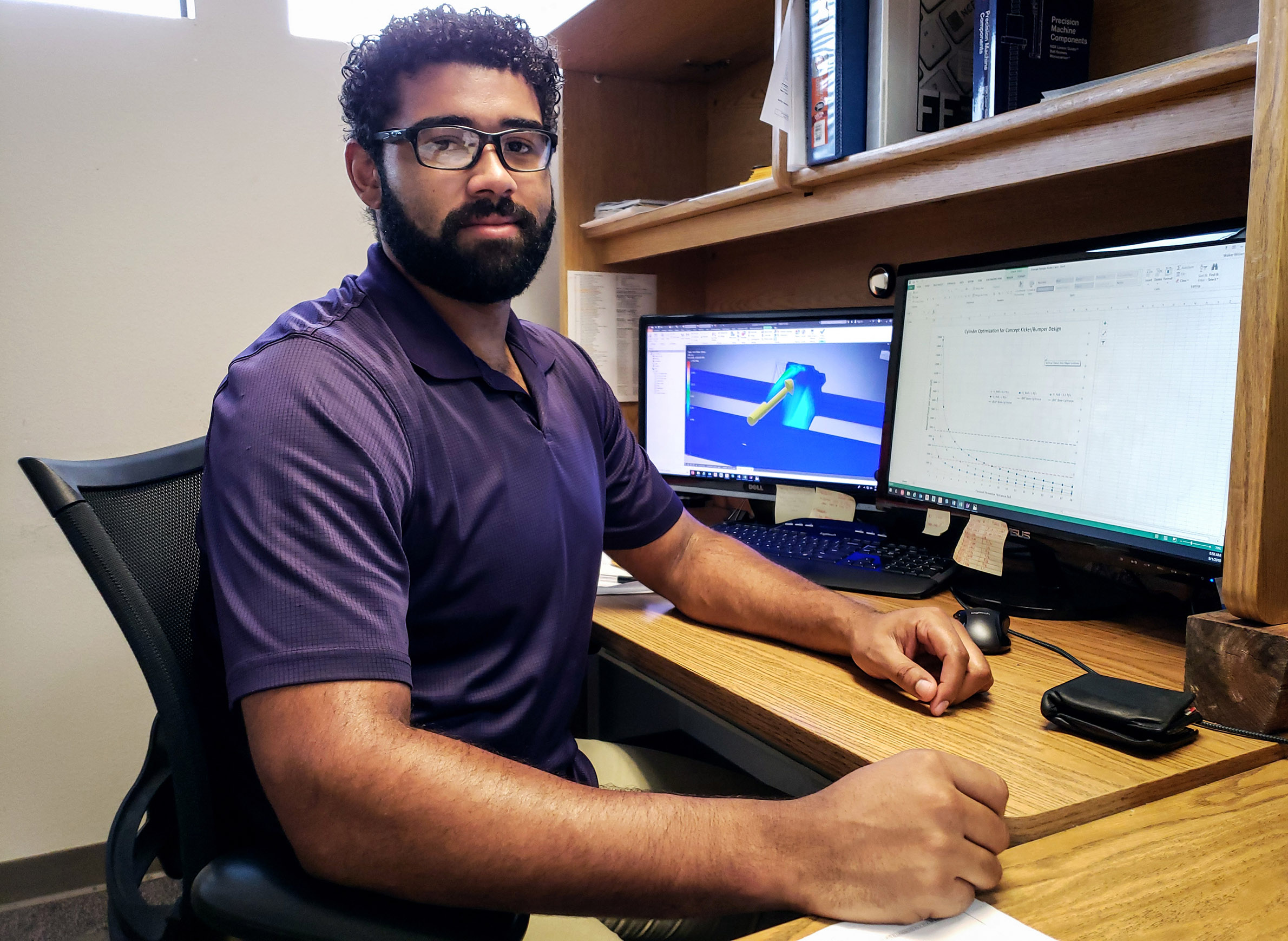

In the months after his last concussion, Walker Williams, who was studying mechanical engineering, experienced acute symptoms that interfered with his classwork.

Williams would get headaches if he looked at a computer screen for too long. He had trouble doing simple calculations for his math classes. He saw a “marked decrease” in his ability to solve problems. He also had trouble remembering things.

“I couldn’t even do my homework,” Williams recalled. “I couldn’t sit down and focus on anything.”

Though the majority of these symptoms improved after a couple of months, Williams said he feared for his future.

“If I can’t do those things, I just wasted four years of my life doing a very hard major, and I wouldn’t even be able to capitalize on that,” Williams said. “I literally would not be able to do my job. So that scared me.”

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy is a degenerative brain disease linked closely to repeated hits to the head. Symptoms of CTE include headaches, mood changes, irritability, anxiety, depression, impulse control issues and memory problems. Some people develop progressive dementia as early as their 40s.

Normally a “very even-keeled” person, Williams said he experienced frequent mood swings. He also started feeling anxiety and depression for no particular reason. Williams said he did not realize brain injuries could change his personality.

‘Wasn’t really worth it to me anymore’

Austin Ramesh is now back in northern Wisconsin, pursuing a certificate in financial advising. He said before playing for the Badgers, he had never experienced anxiety. But halfway through his college career, it started with a “pretty sudden onset.” Sometimes he got so uneasy in class that he had to get up and leave.

“I couldn’t even tell you why,” said Ramesh, a native of Land O’ Lakes. “I just would get, I don’t know, sketched out in class and being around groups of people, big crowds, stuff like that.”

Ramesh skipped his own college graduation because he knew he would not be able to handle being around a crowd that big.

“I was worried that it was going to get worse if I continued to go on. I don’t want it to get … to the point where I just can’t really function at all,” Ramesh said with a sigh. “It just wasn’t really worth it to me anymore.”

Jake Whalen, currently a senior at UW, reached a similar conclusion after suffering three concussions, including one in high school. He feared his symptoms would worsen if he got another concussion, making it difficult to finish his economics degree and entrepreneurship certificate.

“You just decide that your life post-playing career is a lot more important than the in-the-moment playing football,” Whalen said.

Post-concussion symptoms ‘debilitating’

Walker Williams graduated from UW in May 2017 and now works as a mechanical engineer at Globe Machine Manufacturing in Tacoma, Washington. Even though he is only 25, Williams regularly deals with CTE-like symptoms.

“If I played football since fifth grade — and I played it all the way through middle school, all the way through high school, and I played it for four years at the Division I level, all while getting five major diagnosed concussions, including concussions that were unreported, and tens of thousands of subconcussive hits — I’m gonna have CTE. I just know it,” Williams said. “I really don’t like to think about it.”

His short-term memory still has not recovered: he often has a hard time remembering a string of just four numbers. He also has tinnitus, an “annoying” ringing in his ears.

At least once a week for an hour or so at a time, he experiences depression or anxiety that is “completely debilitating, as in, I’m not going to be doing anything productive or talk to people,” Williams said.

“I’ve had weeks where it’s been a couple days, like two days where I can’t — even just talking to people, like sending back a text message, is very, very, very hard,” Williams said. “It’s rare that it lasts that long.”

Williams said he believes he is an “outlier” in terms of the number of concussions he had, and a lot of players come out “pretty much unscathed.”

Concussions keep mounting

In the 2018 season, Badgers football players continue to suffer the effects of concussions. Starting quarterback Alex Hornibrook missed three games this season because of two concussions.

In his most recent injury, Hornibrook’s head hit the ground after he was sacked by a Rutgers defensive player in the Nov. 3 game.

Two years earlier, in November 2016, Hornibrook sustained a head injury that caused him to miss the Big Ten championship game against Penn State. Hornibrook declined to speak with the Center about concussions.

Safety Patrick Johnson left the Badgers after sustaining a head injury during an August 2018 practice. Johnson said his decision to leave was not influenced by the two concussions he had in college, or the three or four he had playing in middle school and high school.

Johnson said he wanted to take a break from football to reduce his stress and improve his mental health. He said he has recovered from any post-concussion symptoms and is considering returning to the Badgers next season.

Context lacking for UW’s concussion data

According to data from the Concussion, Assessment, Research and Education (CARE) Consortium study, 137 concussions were diagnosed from July 2014 to March 2018 among 1,663 UW-Madison student-athletes, with some experiencing multiple concussions.

Ninety-six percent of eligible UW student-athletes have chosen to participate in the $30 million CARE Consortium, the study funded by the NCAA and DOD, so the vast majority of UW-Madison athletes are represented in the data.

Concussions that student-athletes sustain outside of sports, like bike crashes or “college students doing college student things,” are included in the CARE Consortium numbers, said Dr. Alison Brooks, an associate professor in the UW Department of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation, and the principal investigator for the CARE Consortium site at UW-Madison.

“The proportion of those concussions that are not sport-related is not insignificant,” Brooks said. “It represents more concussions than you might think.”

The records released to the Center do not reveal how many student-athletes had multiple concussions. Brooks said “although there aren’t a ton, there are some.”

Jeff Raizner said a student’s health record should stay private, but he is surprised the university would not give out general numbers on concussion prevalence.

“They’re tracking that data, and it’s surprising to me that they’re unwilling to share some of that data to protect the public,” Raizner said.

The Center also obtained injury reports used by the media and sports fans to track injured players. Only football appears to create such reports, according to the UW-Madison

According to those reports, six Badgers football players sustained head injuries in 2016 and five players in 2017. This is on par with a study that found NCAA football teams to have a median number of five concussions per season during the 2011–12 through 2014–15 academic years.

But this does not capture all reported football concussions. UW-Madison did not provide injury reports from the spring preseasons. Additional reporting found two more head injuries in a spring 2016 injury report. After the Center’s open records request was made, two additional players — Hornibrook and Johnson — sustained head injuries, according to injury reports.

Without knowing the concussion breakdown by sport or what proportion of concussions are sports-related, it is impossible to place UW-Madison within a national context.

Concussion Legacy Foundation co-founder and CEO Chris Nowinski said he encourages transparency and the sharing of information, but he understands UW’s desire to shield the CARE Consortium data until the study is properly vetted and published. There is “no reason” to believe UW-Madison athletes have different brain injury risks than students at peer schools, said Nowinski, whose group is dedicated to solving what it calls the “concussion crisis.”

The CARE Consortium data set includes 30 institutions and more than 40,000 student-athletes and military cadets. Brooks said she hopes the study will help answer questions that cannot be answered with small datasets.

“There will be upwards of 4,000 to 5,000 concussions in the database, which dwarfs anything else that anyone else has tried to [get] done,” Brooks said.

Underreporting masks true risk

Even if UW-Madison provided more complete concussion information, Chris Nowinski said it would not show the whole picture of brain injury because so many concussions are unreported.

He cited a 2014 study that found for every one reported concussion, college football players admitted to having six more concussions and 21 “dings” or bell-ringers.

Subconcussive hits, which some researchers think are the “driving force” behind CTE, are also not captured in the CARE data. Nowinski said all studies have this underreporting problem, which makes it hard for student-athletes to assess their own risk.

“The reality is most players still aren’t reporting because those instances where you get hit in the head and have symptoms are so frequent that the players realize if they reported every one, they couldn’t play,” Nowinski said.

Jake Whalen said he experienced this mindset firsthand. In high school, his drive to compete was stronger than his instinct to stay healthy.

“I was playing both sides of the ball in high school, and I would constantly be getting hit all game or doing hits to other kids,” Whalen said. “And I never said anything. I don’t know. I wanted to keep playing, so I just decided not to say anything, as stupid as that sounds.”

Interviews with more than a dozen current and former Badger football players revealed that many downplay the threat of brain injury, even though some said they have had their “bell rung” many times, the Center reported in January 2018.

Concussive hits common, often hidden

In football, players collide on almost every play, so head-to-head hits do not look abnormal unless they are an open field tackle, Chris Nowinski said. Football players also fall down on almost every play, so if they take a couple of seconds to right themselves as they stand up, people do not notice.

Helmets also cover players’ faces, hiding dazed or confused expressions. Nowinski said players can sustain “invisible concussions” in which their heads do not move but their brains are impacted.

When Walker Williams sustained his career-ending hit, no one seemed to notice. Since the hit was near the line of scrimmage, where the defense and offense collide, it did not look out of the ordinary.

From 13:26 to 13:24 on the game clock, Williams stumbled forward a bit, then righted himself.

After the fans in the student section sang “Build Me Up Buttercup,” Williams’ teammates on the field moved forward with the next play. He said the coaches did not realize he had just suffered a major concussion. They just thought he was playing poorly because he kept missing blocks.

“It seems odd to a lot of people, but that’s what a lot of concussions actually are,” Williams said. “Most of the time, they aren’t the big highlight reel hits. It’s a hit that looks to be standard but hits your head in just the right way.”

Ramesh and Whalen had similar experiences. Whalen said when his helmet collided with another player in practice, it was “nothing really out of the ordinary in football.” It wasn’t a “huge hit,” it just made impact at a vulnerable spot on his head, Whalen said.

Ramesh agreed that it is “not necessarily a super-hard collision” that causes a concussion. During the 2017 season, Ramesh got a concussion from accidentally getting kicked in the back of the head.

“It wasn’t a hard kick or anything,” Ramesh said. “But I just got hit the wrong way, and I could tell right away something was wrong.”

The NFL and the NCAA have made rule changes to try to mitigate the risk of brain injury in football. In March, the NFL adopted a rule that banned players from lowering their heads — essentially using their helmets as a weapon. Since 2013, the NCAA has had a similar rule that disallows players from “targeting,” hitting defenseless players above the shoulders.

Ramesh said he thinks the NFL’s no helmet-to-helmet rule is a good change. But, he said, “Football is just a violent game. I don’t think you can really change that. You can’t change the game.”

Nowinski agreed that no matter what the NFL does, danger remains.

Said Williams: “It’s very clear that there’s no way of playing football without putting yourself at extremely high risk of developing CTE.”

Changing his mind

Austin Ramesh initially downplayed the dangers of brain injury. In July 2017, he told the Center that he was not concerned about the potential effects of concussions.

“I’ve never really thought about it too much,” Ramesh said back then. “If I ever start feeling like my health is being compromised by playing football, then I’ll take it from there. But as far as it’s been so far, I feel good.”

In November 2017, after missing a week of practice and a game to recover from a concussion, Ramesh saw the time off as “more of a precautionary thing” that made his mom happy.

In April, he signed with the Arizona Cardinals as an undrafted free agent — on the cusp of his dream of playing in the NFL. It seemed like a fullback spot on the Cardinals’ roster was between him and two other players, according to SB Nation, a sports media website owned by Vox Media.

But once Ramesh was in Arizona for training camp, his anxiety would not subside. It started affecting his day-to-day routine again.

Ramesh talked with his parents, friends, doctors, a Madison researcher and Chris Borland, the former Badgers linebacker who quit the San Francisco 49ers in 2015 because of brain injury fears. Ramesh found out that “concussions and anxiety have pretty much a direct relationship.”

“I ultimately came to the decision that continuing to hit my head and continuing to take any impact to the head really was going to affect my anxiety and just overall, repercussions I was getting from football,” Ramesh said.

Wisconsin Athletics provides fact sheets and presentations to student-athletes about brain injury dangers, including one from the NCAA that explains multiple concussions may put athletes at “increased risk of degenerative brain disease and cognitive and emotional difficulties later in life.”

CTE is not mentioned by name in any of the materials UW provided to the Center.

The UW athletic department “goes beyond” these materials to educate student-athletes about injuries, including information trainers and physicians tell students while providing care, said Justin Doherty, senior associate athletic director.

Nowinski said it is “a major shift in thinking” to have the long-term risks mentioned at all. Still, he would like to see more detail added about CTE and the danger of subconcussive hits.

Attorney Jeff Raizner said he hopes the NCAA lawsuits pressure the league to improve. In June, a similar case went to jury trial. The plaintiff, the widow of a former college football player who was diagnosed with CTE after his death, brought a handful of witnesses and experts whose testimony Raizner described as “overwhelming.” After three days, the NCAA settled without bringing forward its own witnesses.

“The litigation is incredibly important, not just to bring a resolution to this former generation of athletes, but to make the sport safer,” Raizner said. “And to bring hopefully some better information, some better disclosure, better science and better safety to kids in the future.”

Regrets? There are some

Walker Williams said he understands why some would play football despite the dangers.

“It’s a game of risk, you’re rolling the dice. I guess the equivalent is I kind of crapped out and got an unlucky roll,” Williams said. “Knowing the outcome, I definitely would not do it again. But if I got out with no more additional concussions and relatively unscathed, I would.”

Austin Ramesh said he made the right decision to quit when he did. But he would do it all again, even with the anxiety. He said there is a void in his life where football used to be.

Ramesh said he learned life lessons, got a college education and got to live his dream of playing for the Badgers, where he developed connections that gave him the opportunity to pursue financial advising.

“I feel super fortunate to have been able to play for my home state, the team I grew up watching forever,” Ramesh said. “I’ll never take that for granted.”

Jake Whalen said he does not regret quitting — but he misses playing football.

“It’s a very hard thing to walk away from when that’s all you’ve known throughout your life,” Whalen said.

Williams wishes he never played, and he fully expects his mental health will continue to deteriorate. If Williams has a son, he does not want him to play tackle football.

“I know it is likely I won’t have a good quality of life when I get older,” Williams said. “I know that my time clock may be a lot shorter than it would’ve been. My body might be there, but I know things are probably going to deteriorate for me sooner. So, I just try to live as long as I can now.”

Reporter Luke Schaetzel contributed to this report, which was supported by funding from the Ira and Ineva Baldwin Wisconsin Idea Endowment at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us