A Shifting Safety Net For Dairy Farmers Facing Uncertain Milk Prices

As the U.S. dairy industry continues to struggle in the face of ongoing low prices, federal policies intended to support farmers are attracting more attention.

June 12, 2018

Milk can hundredweight and cow feed illustration

As the U.S. dairy industry continues to struggle in the face of ongoing low prices, federal policies intended to support farmers are attracting more attention. One example is the Margin Protection Program for Dairy, which provides payments to farmers when the difference between milk and livestock feed prices fall below a coverage level they select. Introduced through the Agricultural Act of 2014 — better known as the Farm Bill — the program was updated through an amendment to the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018.

“It is an insurance-type product,” said Mark Stephenson, an agricultural economist and director of the Center for Dairy Profitability at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in a June 8, 2018 interview on Wisconsin Public Television’s Here & Now.

“Farmers have to make a decision as to how much protection I need just like we would for auto insurance or fire insurance, and you hope you don’t have an accident,” he added. “But if you do, then it should pay.”

The changes to the Margin Protection Program made in the 2018 federal budget bill significantly reduced premiums, changed the margin period to monthly rather than bi-monthly and extended the deadline for dairy farmers to enroll. This last change allowed participants to reconsider or change their initial coverage amount. The re-enrollment essentially gave farmers a “do-over” and allowed them to collect benefits for time before they enrolled.

“This is unusual because it’s retroactive,” Stephenson told Here & Now. “We get to go back and make a decision about the entire year and we already know that we would be receiving payments at some of these levels of protection.”

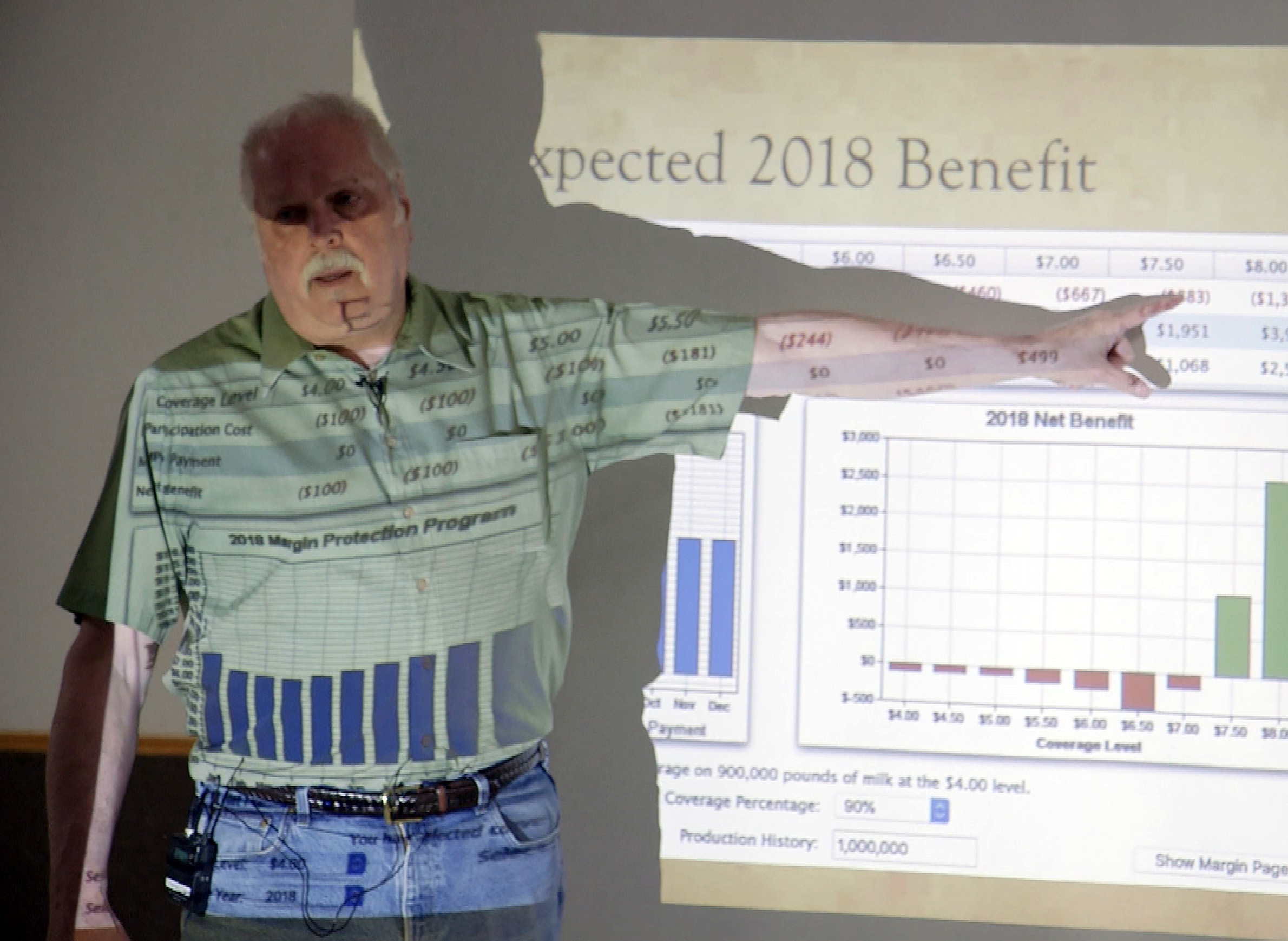

Stephenson was appointed on June 5 to lead a group of industry leaders in the Wisconsin Dairy Task Force 2.0, which is charged with making policy recommendations involving the dairy industry in the state. He discussed the changes to the Margin Protection Program with a group of farmers at the town hall in Trempealeau in May. The meeting was part of a statewide effort to educate farmers and ensure they took advantage of the new change in federal policy.

The Margin Protection Program marks nearly a century of dairy market regulation and support by the federal government, which Stephenson said dates back to the late 1930s.

Early involvement to improve market prices

While the extent and nature of government regulation has shifted since the 1930s, what’s remained consistent for the dairy industry is the idea that the milk market must be regulated. In fact, Marin Bozic, an assistant professor in the University of Minnesota’s Department of Applied Economics and associate director of its Midwest Dairy Foods Research Center, said milk is one of the most regulated food products globally for economic reasons and as well as the health and well-being of consumers.

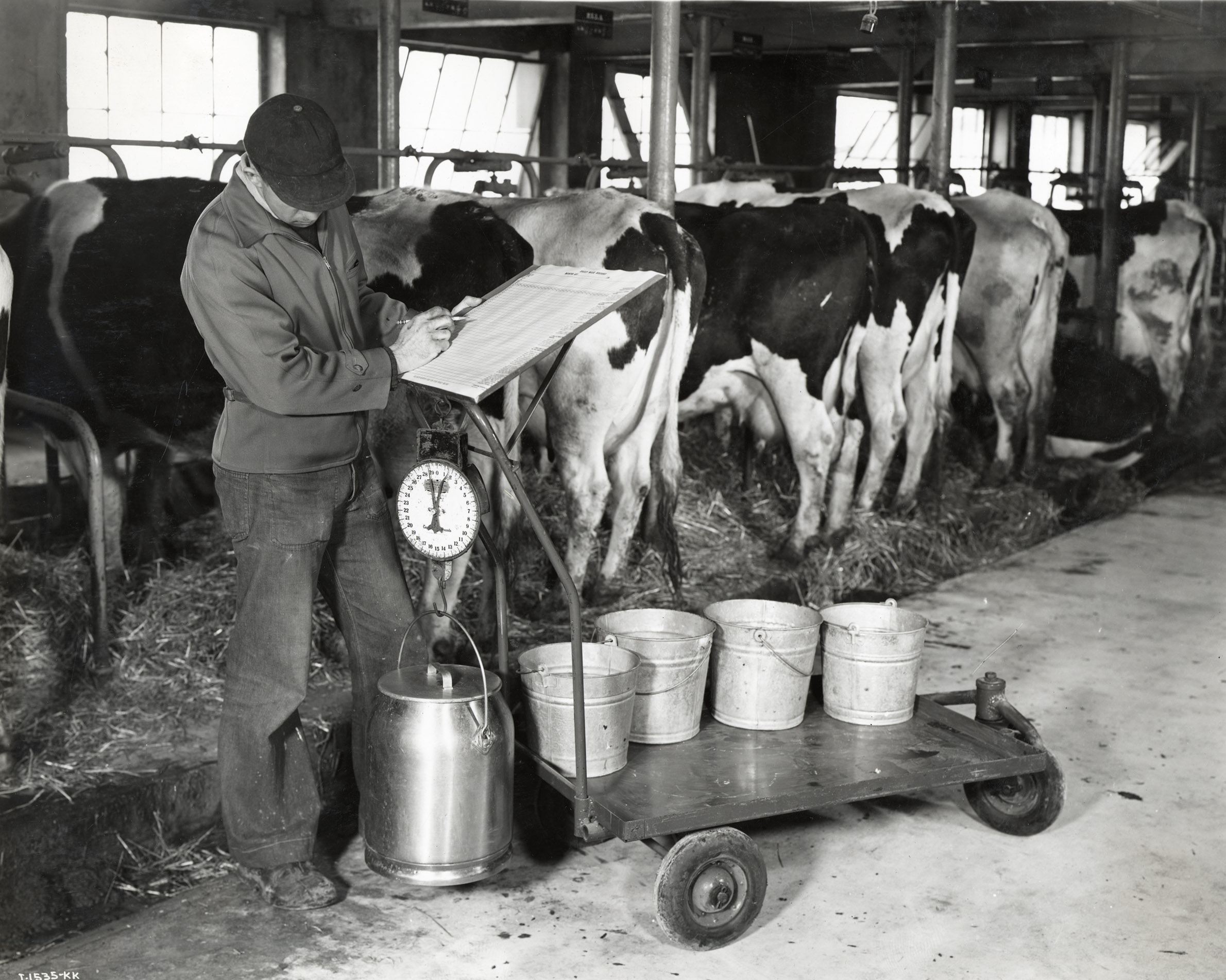

One unique practice embedded in the dairy industry since its inception is the use of cooperatives, a type of business owned and controlled by farmers who produce the milk it sells. According to Brian Gould, professor of agribusiness in the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the very characteristics of milk are an incentive for this business arrangement.

“You’re producing a product that needs to be stored or used within 48 hours,” Gould said. “Historically, we didn’t have good enough transportation systems, so processing plants had local monopolies because farmers had no choice but to ship to that plant.”

The 1930s marked the beginning of government support for dairy producers. And as Stephenson told Here & Now, the focus then was to improve overall market prices. When market prices fell below minimum set prices, the government stepped in to purchase products above those guaranteed prices.

“It wasn’tfor an individual farmer. It was to move prices up for everybody,” Stephenson explained.

Eventually, though, inflation caused prices to rise and the “government ended up with mountains of milk and cheese,” said Bozic. By the 1980s, during the administration of President Ronald Reagan, the federal government moved to address the milk industry differently, said Bozic.

Managing milk supply and global markets

In 1983, policymakers enacted the Dairy Production and Stabilization Act, the federal government’s first attempt at controlling milk supply in the U.S. Just two years later, they passed the Dairy Termination Program, another attempt to control supply in which the government would buy out dairy herds under the stipulation that farmers would remain out of the industry for five years. But how would reducing the number of cows in the U.S. stimulate the dairy industry? At the time, cows were beginning to produce milk at a faster pace than U.S. population growth and consumption levels, largely due to better nutrition and herd management, and the use of artificial insemination, vaccines and artificial growth hormones.

“For supply to balance with demand, we had to increase per capita consumption, or export more, or just have less cows,” Bozic explained.

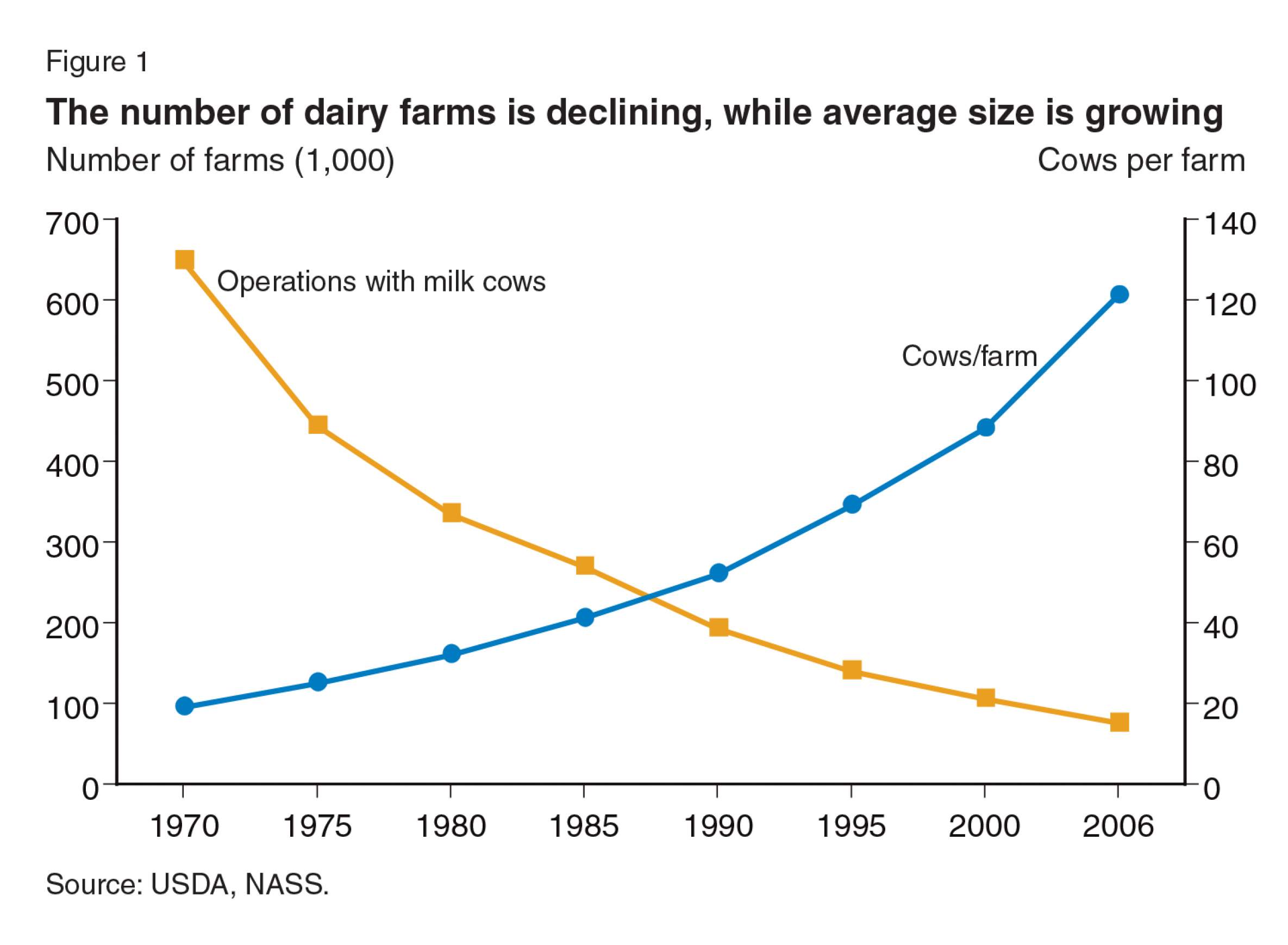

In the 1970s and ’80s, the number of dairy farms in the U.S.decreased, although the average size of these farms increased. Research by Gould indicated that in 1970, there were approximately 648,000 dairy farms with 12 million cows, yielding a total milk production of 117 billion pounds. By 2016, however, there were only 51,000 farms, with 9.3 million cows producing 212 billion pounds of milk.

Consistent with national trends, Wisconsin milk production has also increased over this period, from 18,435 million pounds in 1970 to 30,320 million pounds in 2017. Additionally, since 2004, the number of dairy cow herds has dropped from 15,904 in January of that year to 8,801 by January 2018.

Meanwhile, by the 1990s, dairy exports started to increase, opening new markets for American dairy farmers. However, according to Bozic, policymakers at the time determined that dairy policy was inconsistent with a desire for more exports.

When the 2002 Farm Bill was enacted, a program known as the Milk Income Loss Contract, authorized payments to farmers when prices fell below a determined level.

The federal government subsequently decided to do away with its decades-long policy of price support, and instead, introduced a risk-management program that placed more responsibility on individual farmers: the Margin Protection Program.

Developing the Margin Protection Program

Designed between 2010 and 2013, the intention of the Margin Protection Program was to offer dairy farmers financial protection against declining profit margins. While the law was drafted in the wake of the Great Recession, feed prices were volatile, causing cost uncertainties for farmers feeding their cattle corn, hay and other types of fodder. That difficulty, coupled with a desire to make the U.S. a more competitive dairy exporter, were the motivations for the program.

However, after the Farm Bill passed in 2014, corn prices became more stable and the set premiums that were determined from feed prices in years prior no longer worked.

“Unfortunately, it was battling a war that just finished,” said Bozic.

The program was not working as intended or advertised. Additionally, many dairy farmers found that they were not receiving their payments during tough economic times.

“The program never came into play — it wasn’t effective,” Gould said, noting that farmers were forced to make their decision on coverage over an entire year just once, without knowledge of how the market might swing in upcoming months.

As a result, Congress chose to return to the issue, and implemented changes to the Margin Protection Program in February 2018. However, as Bozic observed, legislators seemingly “forgot to change the name of the program.”

Since the changes were retroactive, potentially interested dairy farmers may have been unaware that the updates, which were meant to benefit them, were even made.

“Imagine if there was an insurance product that said, ‘Oh your house burned down, let me buy house insurance.’ In a sense, it is not a realistic proposition,” said Bozic.

Even if struggling dairy farmers take advantage of changes to the Margin Protection Program, the benefits might not be entirely a “game changer” as much as participants might hope, said Bozic.

Gould added that the changes are “clearly a buyoff of dairy farmers.”

Regardless of the effects that the updated Margin Protection Program may have on dairy farmers in 2018 and beyond, educators, researchers and USDA representatives have worked since February to educate dairy farmers about the changes, hosting events like that in Trempealeau and others across Wisconsin and the U.S.

Bozic and Gould each noted that proposed legislation for dairy farmers is even more generous and flexible than current policy, but as of June 2018, an updated farm bill has not been passed, though the program’s deadline was extended once again. Proposed legislation replaces the words “Margin Protection Program” with “Dairy Risk Management Program.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us