A New Hemp Industry Sprouts In Wisconsin, Boosted By CBD Enthusiasm

Wisconsin launched an industrial hemp pilot program in 2018 and now has more than 2,100 applications for licenses in 2019.

May 12, 2019

Hemp field in Wisconsin inspection 1

When Abbie Testaberg married her husband, Jody, in 2010, she told him to quit his job. He had been working for a medical marijuana co-operative in California when the couple met in Wisconsin.

“I wanted him to forget what he was good at and passionate about and get a real job and we could move on with our lives,” Testaberg said.

He did that, and moved to River Falls in western Wisconsin. There, the Testabergs and Abbie’s mother ran a cafe. One year later, the Testabergs’ first child was born with a chromosome abnormality, and two years later, her younger son was born with spina bifida, a failure of the spine to grow properly.

Abbie Testaberg did all she could to keep their children healthy, and part of that included pursuing alternative treatments in addition to Western medicine. This exploration of alternatives led Testaberg back to her husband’s previous job — cannabis.

“Thinking about alternative healing and wellness options for my kids opened me to the realities of medical cannabis, which my husband already knew,” Testaberg said. ‘On the journey, so far, my biggest interest is better understanding the plant and the endocannabinoid system to consider how my children may benefit.”

Now, nine years after she told her husband to quit working with cannabis, Testaberg has devoted her career to it, and to the production of one form of the plant — hemp — which recently was legalized in Wisconsin.

Testaberg is an authorized hemp grower and processor in Wisconsin, which launched an industrial hemp pilot program in 2018 and now has more than 2,100 applications for licenses in 2019.

Industrial hemp is a member of the Cannabis sativa plant family — the same family as marijuana. The plant looks essentially the same but has been bred to contain less than 0.3% of tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the chemical that causes the “high” in marijuana. In comparison, marijuana seized by federal officials averages about 12% THC.

Some hemp license holders say they are growing the plant now in anticipation of legalization of marijuana in Wisconsin, which is gaining support from Democratic Gov. Tony Evers and a growing numbers of lawmakers. But legalization still has many opponents in the Republican-controlled Legislature, and GOP leaders voted to strip decriminalization and medical marijuana legalization from Evers’ budget.

Wisconsin a historical leader in hemp

In the early 1940s, Wisconsin led the country in the production of hemp. University researchers began growing hemp in 1908, and by 1917, farmers had 7,000 acres under cultivation. During World War II, demand for hemp increased due to its utility for making rope. At one point during the war, Wisconsin had 42 hemp mills across the state.

Wisconsin’s climate and farming industry make it an ideal environment for growing hemp, according to Irwin Goldman, professor and chairman of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Horticulture.

“We have a diverse agricultural climate in Wisconsin. We obviously have a big dairy industry but we also grow a lot of fruits and vegetables, we have forages to feed the dairy animals, we have lumber for paper,” Goldman said. “A crop like hemp was a really good part of that. We did a lot of different things and it fit well in our environment.”

In 1970, industrial hemp got swept into the federal Controlled Substances Act along with marijuana and became a Schedule I drug. This effectively placed a ban on growing the crop in the United States for nearly 50 years. Hemp largely disappeared from Wisconsin’s landscape.

Farmers in Wisconsin first started planting hemp again in May 2018, after Wisconsin’s industrial hemp bill (A.B. 183/S.B. 119) passed unanimously in 2017. Act 100 authorized a pilot program for growing hemp in Wisconsin with specified regulations from the state Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Production.

That legislation was made possible by the 2014 U.S. Farm Bill, which ended the decades-long ban on hemp, allowing states and universities to set up industrial hemp pilot programs.

Modern day hemp has numerous uses, including fiber products, building materials such as drywall, paper, biofuel, food such as cereal and bread, cosmetics — even jeans. Hemp also can be used to make cannabidiol, or CBD, a non-intoxicating substance used for a variety of medical conditions.

Hemp helps Wisconsin farmers

State Sen. Patrick Testin, R-Stevens Point, who was the lead sponsor of Act 100, sees hemp as a way to support Wisconsin farmers, who are facing record low commodity prices and loss of dairy farms.

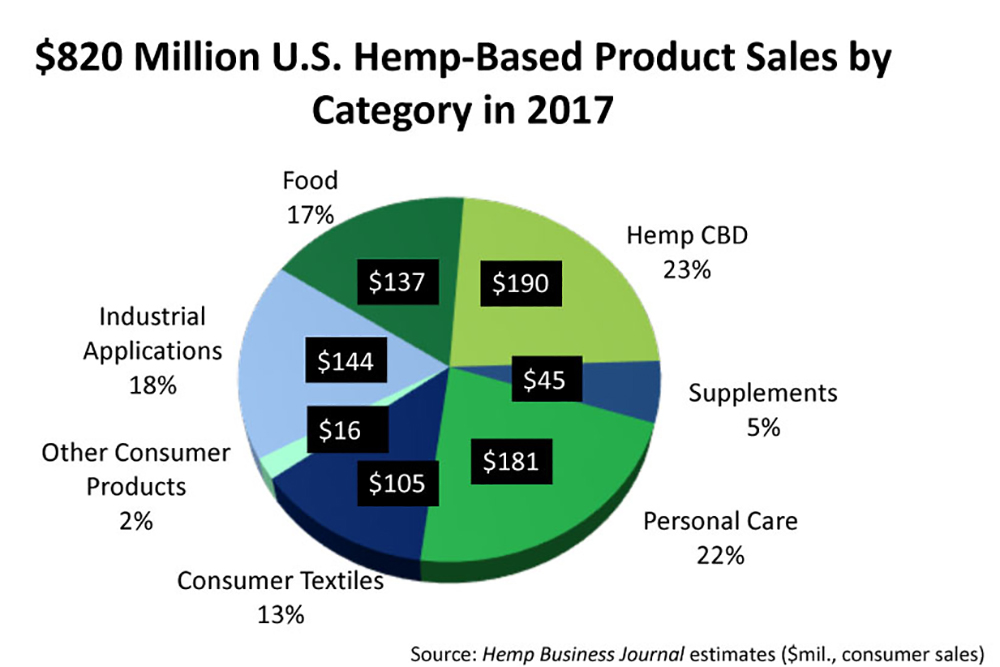

Hemp can function as a rotational crop that would help farmers increase their crop diversity, boost farm revenue and provide opportunities for new innovations with the plant. In 2017, there were $820 million dollars in hemp product sales in the United States. The Hemp Business Journal estimates this will grow to $1.9 billion by 2022.

“This is an opportunity for us to reintroduce a crop that we once led the nation in, to help our farmers raise up their margins but more importantly, the research and innovation is going to open the door here in the state of Wisconsin,” Testin said. “I am thoroughly convinced, and I’ve said this over and over again, that within the next five to 10 years, Wisconsin is going to be the national leader in industrial hemp again.”

The Testabergs were one of the 135 growers that planted seeds in the first year of the hemp pilot program in Wisconsin. In 2018, a total of 1,850 field acres and 22 greenhouse acres were planted statewide, according to Jennifer Heaton-Amrhein, a policy analyst at DATCP.

Applications to grow and process hemp have grown dramatically for the program’s second year — over 2,100 people have applied for the licenses in 2019. Gov. Tony Evers has recommended adding five full-time positions and an additional $300,000 to support the program in his proposed 2019-21 budget.

The program is supported in part by fees, including a one-time $150 license fee, $350 annual registration and $250 annual sampling cost. These are some of the lowest in the country, according to Testin.

Participants must provide the exact coordinates and GPS directions to their growing or processing facilities; the names of license holders are confidential to prevent theft. Before harvest, DATCP tests the plant for its THC content; anything above 0.3% is considered marijuana, and the state orders it to be destroyed. Additionally, participants must pass a background check. Anyone with a felony drug conviction is banned from the program.

State, federal laws clash

Wisconsin officials are striving to update state regulations to conform to the 2018 U.S. Farm Bill.

“The only constants in the industrial hemp program are change and ambiguity,” DATCP policy analyst Jennifer Heaton-Amrhein said. “There are a lot of gray areas, and the reason is that there is this merging of federal laws and state law, and they’re not necessarily consistent.”

Many of these inconsistencies are addressed in Senate Bill 188, known as “Hemp 2.0” or the Growing Opportunities Act, a bipartisan bill that state Sen. Patrick Testin introduced on April 30, 2019.

The bill would update the definition of hemp to reflect that of the federal bill, redefine marijuana to exclude hemp, remove THC found in hemp from the controlled substances list, and prohibit a person from producing hemp for 10 years following a drug-related felony conviction. Currently there is no limit on how old the conviction can be.

These legal ambiguities had real consequences for the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin. After the 2014 Farm Bill allowed states to implement industrial hemp research pilot projects, the tribe voted to create its own in 2015.

In July 2015, Marcus Grignon and other Menominee tribal farmers planted industrial hemp on about 3 acres of the reservation in northeastern Wisconsin. Three months later, on Oct. 23, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration raided the farm and destroyed the 33,000 plants.

The tribe sued the federal government, arguing its program was legal under the 2014 federal legislation. But a judge disagreed, saying the legalization only applied to state-run hemp programs. Grignon has since enrolled in Wisconsin’s industrial hemp program, which launched in 2018.

“Hemp is growing again in tribes, it’s growing again in Wisconsin, and it’s growing again across the nation,” he said.

CBD is biggest hemp product

Hemp can be grown for grain and fiber, but the most popular form across the United States is for making CBD. Hemp-derived CBD accounted for 23% of the hemp-based product sales in the United States in 2017, according to the Hemp Business Journal.

Growing hemp for grain or fiber and growing for CBD are different processes, said James Jean, the business developer at Legacy Hemp, a company that works with farmers in Wisconsin, Minnesota and North Dakota.

CBD plants require more hands-on labor and are often grown indoors. They also can be much more expensive. Seeds can be between $1 and $5 each, while Legacy Hemp, which only sells grain and fiber seeds, charges $4 a pound — each of which includes thousands of seeds. CBD is expensive, and farmers stand to make a high income from producing it — but it can be risky.

Raw CBD material can sell for $50 to $150 per pound to a processor, and purified CBD can sell for around $2,700 per pound, Abbie Testaberg said.

However, infrastructure for processing and selling hemp is still developing in Wisconsin, and farmers face the risk of not having a buyer for their crop, Jean said.

“The hype is in the CBD side, and there is a big market for that,” Jean said. “But we believe that market bubble is going to pop, because everybody is jumping into the game right now. If you don’t have a buyer and contract on paper going into it, it’s going to be a scramble at the end of the season to get the yield and the cash flow that people are expecting.”

Another risk in growing hemp for CBD is the possibility that the crop will be above the 0.3% THC levels. This happened to 21 of 295 samples in Wisconsin last year, including one of Testaberg’s. She had to destroy a small amount of her crop that tested “hot.”

Almost all CBD varieties will go above 0.3% at some point of the season, Jennifer Heaton-Amrhein said. This depends partly on the genes of the seed — DATCP has banned the use of one variety, C4, as most crops of this variety came up hot in 2018. Farmers are responsible for testing the crop regularly at private labs and harvesting at the right time to ensure their crop is under 0.3%, she said.

A UW-Madison project is researching how THC levels vary in hemp, a problem that is not well understood. The year-long project was awarded $35,000 to explore best practices for production and harvest so farmers can avoid having to destroy crops.

‘It’s Hemp, It’s Fine’

The CBD trend has made its way to Madison in a big way. On a Sunday morning in April 2019, nearly 500 people attended It’s Hemp, It’s Fine, billed as Madison’s first-ever hemp/CBD expo. The event was put on by The Healthy Place, formerly known as Apple Wellness, a Wisconsin company that sells CBD products. Attendees could test CBD everything — tequila cocktails with a few drops of CBD oil, IPA beer brewed with CBD powder, CBD-infused coffee beans and chocolate.

Besides the samples, Wild Theory Company, a Verona-based CBD retailer, sold a bottle of pills for $60 and $380 for up to 2 ounces of tincture. Ella Wood, a consultant for The Healthy Place, said these prices are average for local CBD products.

Key stakeholders in the hemp industry also answered questions from the audience at the expo — such as how farmers can secure seeds that are certified, how DATCP will handle the exponential increase in licensing, and organic designations for hemp production.

Jeff Oler and his daughter, Elizabeth Pierson, are newly enrolled in Wisconsin’s hemp program. Both use CBD as an alternative medicine, and plan on growing CBD-rich hemp on 1 acre of land near Richland Center. Oler waited to join the program until the second year — he wanted to see what happened during the first year before investing.

But they have faced difficulty in finding and connecting with other growers, processors and buyers because of the confidentiality in the program.

CBD is ‘wild, wild West’

The legality of CBD depends on how it is marketed. If companies are just bottling it up and selling it, that is legal. But if they are marketing it as a cure to any sort of aliment, it is not legal. Still, it is hard to enforce, and Jennifer Heaton-Amrhein says it is “the wild, wild West out there” when it comes to CBD.

Indeed, there have been a number of incidents in the state where products have claimed to be CBD, but after being tested, they either come back with no CBD, or above the 0.3% THC concentration limit, state Sen. Patrick Testin said. The new bill also clarifies this; it would prohibit the mislabeling of hemp products.

Abbie Testaberg grows CBD-rich hemp on her farm and says the only way to know if something is legal is to try it.

“You have to take a lot of risks in saying: ‘I know I can do this and I’m gonna do it, and they’re gonna tell me I can’t, and then I’m gonna go to court and I’m gonna win,'” Testaberg said. “And that’s expensive, and it’s dangerous, and not very many people are as crazy as we are to do that.”

In addition to her hemp farm, Testaberg is also pursuing multiple cannabis-related businesses, including the production of a system to grow cannabis without soil, a CBD store that will open in the next few months in Wisconsin, and PhytoPharm.D, a company that educates and consults with patients, producers and dispensary operators about cannabis-based-medicine.

Growing wave?

Growing CBD-rich hemp is very similar to the process of growing marijuana, a plant that is rapidly becoming legal in states across the country. State Sen. Patrick Testin said that some participants in the hemp program are learning to grow the plant because of its similarity to marijuana, with the hope that someday it will be legalized.

“We have to remember that Wisconsin is very far behind on legalization,” Abbie Testaberg said. “The likelihood of the legalized environment being so open that all of these farmers are going to have the same possibilities as they do in hemp is pretty low.”

Testin said he is “not there yet” on legalization of recreational marijuana, but is working with a team to explore options for the legalization of medical marijuana in the state.

“But at the same time we have to manage expectations, because there are a number of my colleagues in the Senate who are not supportive of any form of either medical or recreational, so it is going to take some time,” Testin said.

This story was produced as part of an investigative reporting class in the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication under the direction of Dee J. Hall, managing editor of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism. The Cannabis Question is a series exploring questions about proposals to legalize marijuana in Wisconsin. The Center’s collaborations with journalism students are funded in part by the Ira and Ineva Reilly Baldwin Wisconsin Idea Endowment at UW-Madison. The nonprofit Center collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us