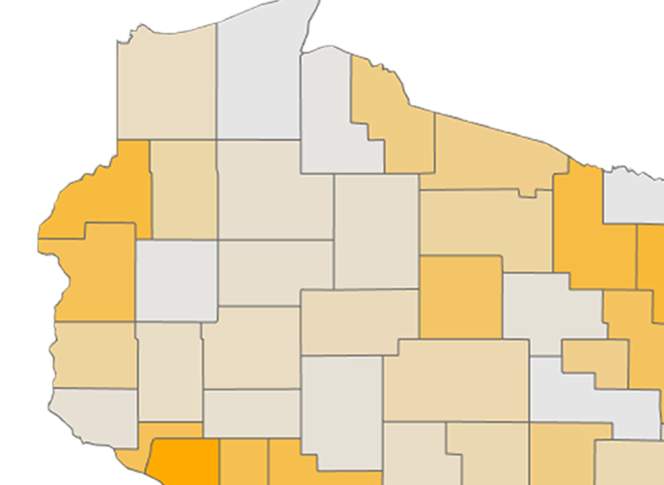

Wisconsin's Youth Mental Health Challenges Vary By Region

In Wisconsin, the reality is that schools — not unlike local police departments are increasingly de facto providers of mental health services to the public.

May 18, 2016

Data source: Wisconsin Department of Health Services

In Wisconsin, the reality is that schools — not unlike local police departments — are increasingly de facto providers of mental health services to the public.

With that in mind, from 2015 to 2019, the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction will roll out its new Wisconsin School Mental Health Project in 27 school districts around the state. The project is focused on better equipping existing teachers, administrators, school psychologists and social workers for the task.

“Especially in the more rural parts of the state, we hear people saying that there aren’t resources available, and teachers and first responders are the ones trying to diagnose people and refer people to services,” said Julianne Carbin, executive director of the Wisconsin chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. “I honestly think schools and families are spread really thin.”

Many reports from government agencies and advocates point to a dearth of mental health resources across the state. As of 2013, the federal government designated 44 Wisconsin counties, along with parts of Milwaukee and Rock counties, as mental health professional shortage areas. The designation means that an area has a ratio of 30,000 or more residents for one full-time psychiatrist, or 20,000 to one for areas with high instances of alcohol and substance abuse.

That shortage area designation encompasses both adult- and child- or adolescent-focused psychiatrists. But data suggest that mental health issues in Wisconsin are especially hard on children.

Understanding Wisconsin’s youth suicide problem

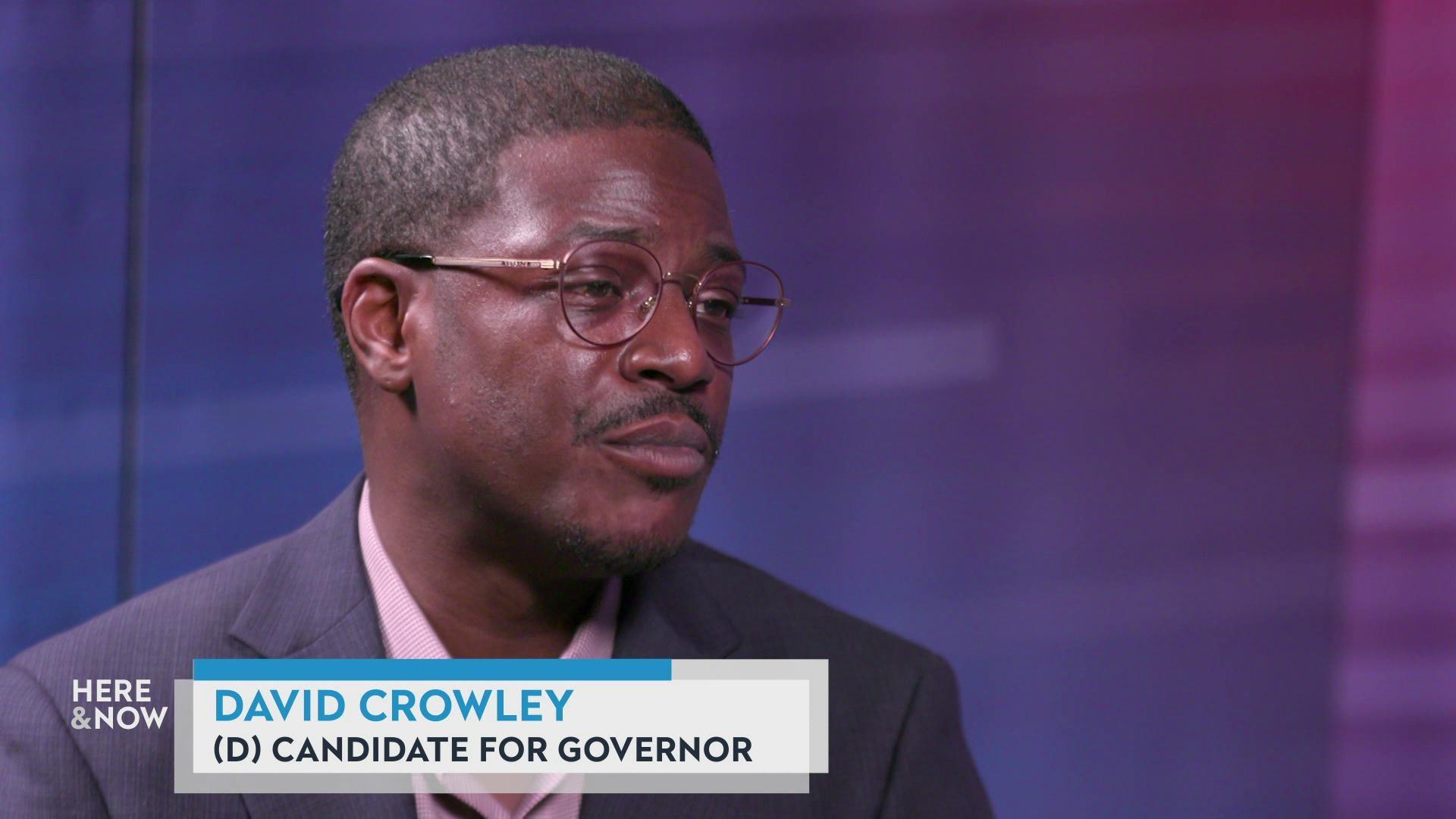

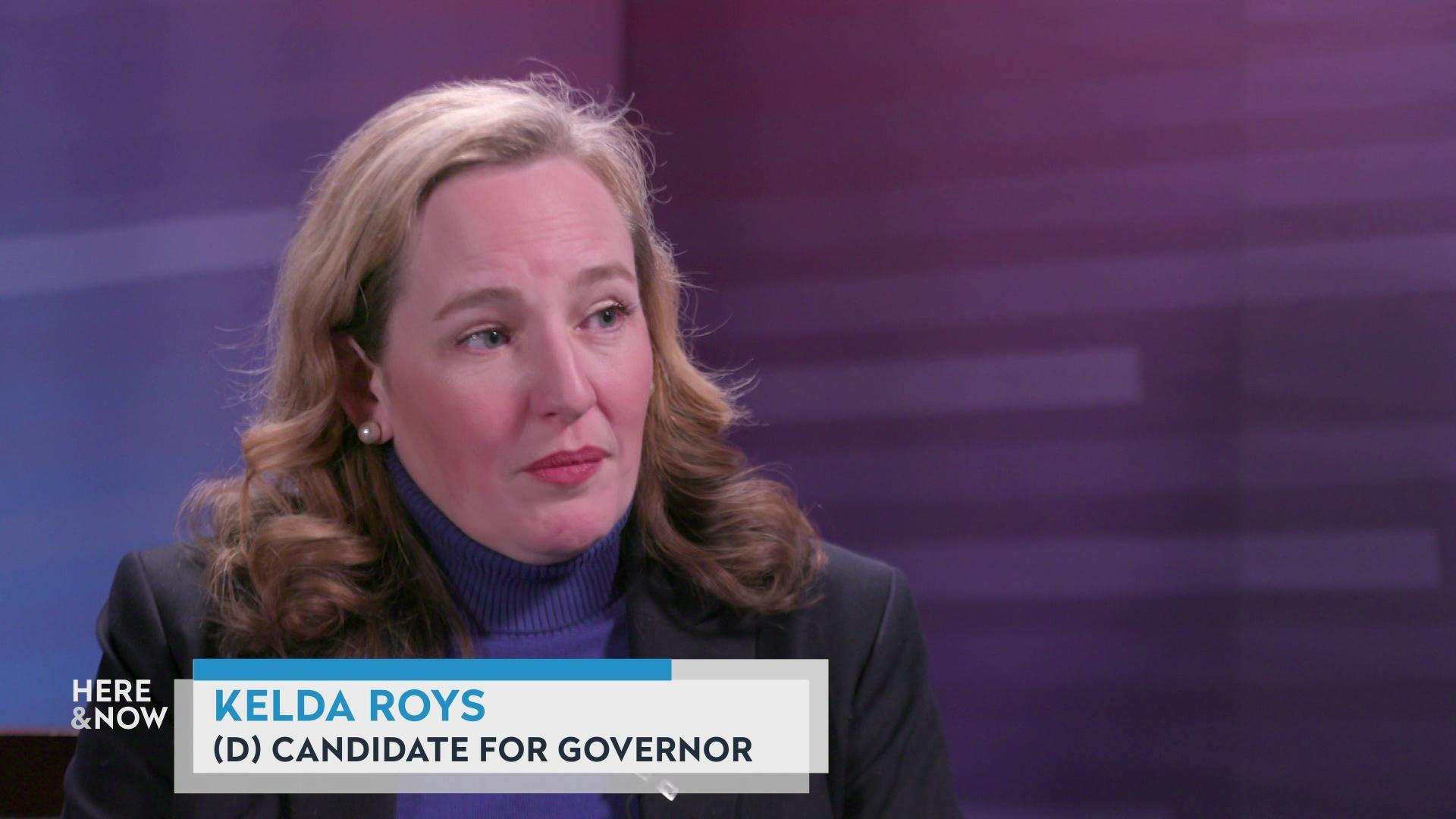

In an Aug. 21, 2015 interview on Wisconsin Public Television’s Here And Now, Steve Fernan, assistant director of the student services team at DPI, cited data that show Wisconsin’s youth suicide rate surpassing the national average in almost every year from 2000 to 2013.

DPI used statistics from the state Department of Health Services and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to examine how many children ages 5 to 19 died by suicide in Wisconsin and across the country. In 2013, the most recent year for which complete data are available, the national suicide rate for this age group was 3.44 per 100,000 youth. In Wisconsin, the rate was 4.18. From 2000 to 2012, Wisconsin lost 616 people in this age range to suicide.

Of course, suicide isn’t the only indicator of a population’s mental health needs, and in fact, youth aren’t the age group with the highest suicide rate in Wisconsin. Adults between the ages of 45 and 54 are the Wisconsinites who most commonly die by suicide, according to the 2014 DHS report, The Burden of Suicide in Wisconsin 2007-2011. That report does show, however, that young people between the ages of 15 and 24 have the highest rate in Wisconsin of hospitalizations and emergency-room admissions for self-inflicted injuries. It is necessary to stress that not all self-inflicted injuries are suicide attempts, and in fact the mental health profession regards the two problems as distinct.

Among Wisconsin’s overall population, white people have the highest suicide rate. But the report showed that non-white students were far more likely to report attempting, planning or considering suicide within the past 12 months.

A University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension fact sheet on teen suicide notes that teenage girls are more likely than boys to attempt suicide, but boys are more likely to actually die by suicide because they tend to use more lethal means.

It also says that teen suicides and suicide attempts might be underreported due to the stigma attached to mental illness. Despite the shame and stigma attached to these issues, its authors observe that teens “report that they are often relieved” when they have the chance to discuss mental-health issues with a family member or a professional.

The DHS report also broke down suicide death rates, hospitalizations and ER admissions for self-injury and unmet mental health needs by county. It reveals an unmistakable trend: The counties with the highest rate of these problems, and the highest ratio of population to mental-health providers, tend to be concentrated in western and northern Wisconsin.

This geographical disparity also holds true when one looks at where the 616 Wisconsin youth who died by suicide from 2000 to 2012 lived. Heavily populated southern Wisconsin counties, including Milwaukee, Waukesha and Dane, had the highest total number of youth suicides. But when analyzed as a percentage of the youth population in a given country, the trend is once again unmistakable: The highest age-adjusted death rates for youth suicides were all in more rural counties, including Buffalo, Trempealeau, Jackson and Polk on the western side of the state, or Door and Marinette in its northeastern region.

In his Here And Now interview, Fernan said at least some of Wisconsin’s high youth suicide rate can be attributed to the wide availability of firearms in the state (both nationally and in Wisconsin, guns are overwhelmingly the most common method of suicide) and a high rate of alcohol abuse. But Fernan also acknowledged that the rate is a problem of resources, and said the DPI initiative is overdue.

“Our state has a much lower than national average rate of child psychiatrists available per 100,000 population, and then finally there’s the stigma — that’s not just in Wisconsin, that’s everywhere,” Fernan told WPT. He went on to explain that DPI’s program would help address the stigma by training school staff to be more sensitive to the trauma that students experience and take positive steps to encourage mental health as opposed to just reacting to negative situations.

Fernan said he hopes multiple state agencies can better coordinate with each other in addressing mental health. That theme is also prominent in the first official report from Wisconsin’s recently established Office of Children’s Mental Health. The Legislature created the office in the 2013 budget bill signed by Governor Scott Walker. The new office’s total funding for 2013 to 2015 is $535,400. In its report, released in 2014, the office focused on the need to improve communication and reduce duplicated efforts among the various public agencies that deal with children’s mental health, including DPI, DHS, the Department of Children and Families, and the Department of Corrections. And multiple resources from UW-Extension detail how students’ families can play a stronger role in their mental health support structure.

The increasingly collaborative, participatory mindset around mental health in Wisconsin is one reason NAMI Wisconsin’s Carbin said she is optimistic about the DPI initiative and other mental-health efforts on the state level.

“There seems to be a lot more collaboration and coordination that all of these groups are coming together and figuring out,” she said.

Taking first steps in Wisconsin schools

The schools where the Wisconsin School Mental Health Project is launching often are not always located in the counties with the most dramatic indicators of need. Of the initial 27 participating school districts, none fall in Buffalo County or neighboring Trempealeau County, both of which ranked among the most afflicted in the state based on multiple measures in the state’s Burden of Suicide report.

Carbin doesn’t see that as a reason to criticize DPI’s initiative at this stage, though. In addition to factoring in a region’s needs, she said, mental health efforts like this need to focus on areas where public officials and community members at all levels are serious about putting aside the stigma of mental illness and tackle the issues in all their complexity.

“A community really has to be ready and open to taking on this kind of initiative and open to finding a solution,” Carbin said. “If communities are open to having these kinds of conversations, these are the communities we should move forward with.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us