Why Waukesha Rebranded Its Bid For Great Lakes Water

The city of Waukesha spent more than a decade seeking approval to source its drinking water supplies from Lake Michigan.

March 14, 2017

Great Water Alliance illustration

The city of Waukesha spent more than a decade seeking approval to source its drinking water supplies from Lake Michigan. Before getting permission in 2016from the governors of eight Great Lakes states, the city had to gather scientific evidence to make its case for using this water and navigate a complex binational agreement, the Great Lakes Compact.

Now it’s time for Waukesha to pursue support for something a bit more commonplace: a construction project.

At the beginning of March 2017, city officials announced the launch of the Great Water Alliance, a promotional campaign and accompanying website. According to the Milwaukee Business Journal, Waukesha spent $42,000 for this effort to muster public support for its tapping of Lake Michigan water. However, this campaign is not aimed at influencing the debate over whether Waukesha should be allowed to get the water — the city already has permission, and Mayor Shawn Reilly and water utility manager Dan Duchniak are confident they’ll prevail in an administrative appeals process that will kick off in earnest with oral arguments in Chicago on March 20.

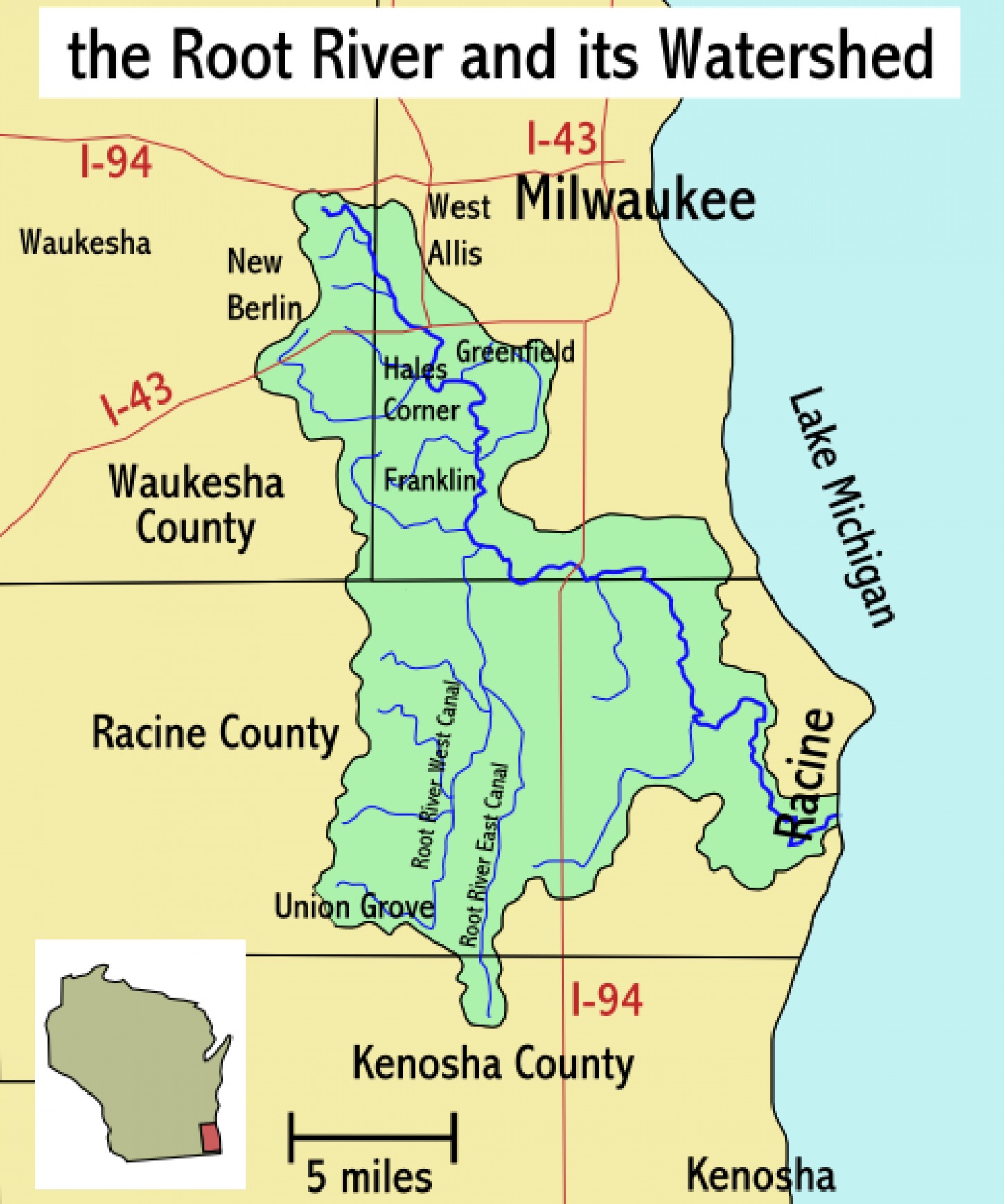

Rather, the Great Water Alliance is about all the work the city will have to do to build the necessary infrastructure to get that water — namely, a pipe running from the Oak Creek Water & Sewer Utility plant to Waukesha, and another pipe running from Waukesha’s wastewater plant to a site on the Root River in Franklin, from which treated wastewater will flow back into Lake Michigan. (Under the terms of the agreement, Waukesha has to return about as much water as it takes out of the lake.) This work won’t begin until 2019 at the earliest, because Waukesha still has to finalize the specific routes of the pipes and secure construction permits.

The slick Great Water Alliance website features promotional information about the project, including a teacher’s kit, and aims to counter what Duchniak considers misleading information about the long-term significance of the science involved. It will also serve as an online presence for public meetings about the project, and will share water-quality data the city is gathering from the Root River. The campaign is intended not just for residents of Waukesha, but likewise residents other nearby cities along the water pipeline’s likely route.

“For us, the Alliance is in southeastern Wisconsin and those communities that will be impacted by our project or the projects — Waukesha, New Berlin, Muskego, Franklin, Oak Creek, Caledonia and Racine,” Duchniak said. “Therefore we view this project as an Alliance between those communities.”

“Great Water,” as a press release notes, is the English translation of “Michigami,” traditional Ojibwe name for Lake Michigan. (This explanation might recall Alice Cooper holding forth on Milwaukee history in Wayne’s World.) Waukesha officials and others who worked on the campaign also like to note that they’re hoping to provide the city’s residents with great water.

What doesn’t translate quite so neatly is the “Alliance” portion of the name. The Great Water Alliance was not born when officials from all these southeastern Wisconsin municipalities signed a formal pact to advance Waukesha’s water project. The closest equivalent is Waukesha’s deal with Oak Creek to obtain the water itself, which would add Waukesha to the already complex networks of eastern Wisconsin utilities that share access to Lake Michigan.

For instance, Muskego water utility manager Scott Kloskowski, said he read about the campaign in a newspaper article. In an interview, Kloskowski said he thinks Waukesha’s plan is well-thought, and believes a water pipeline passing through Muskego would benefit the city if it ever decides to switch to Lake Michigan water itself. Muskego Mayor Kathy Chiaverotti said she looks forward to discussions with Waukesha officials, but has yet to have much formal contact with them about the project.

Meanwhile, Racine Mayor John Dickert has long opposed Waukesha’s plan, because he fears that wastewater will harm the Root River’s quality and discourage fishing and other recreation as it flows through his city. Observers in other states have also questioned whether Wisconsin will be able strongly enforce environmental regulations.

A marketing creation

The Great Water Alliance campaign was born at Mortenson Safar Kim, a Milwaukee advertising firm, and is a creation of the branding process as much as one of local government planning.

Patrick McSweeney, MSK’s vice president of public relations, said the agency — working with engineering and lobbying firms the city employs — developed the name as a way to encapsulate a complex public works project that people will experience in different ways. Some residents of southeastern Wisconsin may experience the Waukesha Water Diversion — the entire project’s more official, less snappy name — as merely an abstraction as they follow environmental and political debates about it. Others will encounter it in the form of detours and delays as crews tear up (and eventually replace) roads in their communities to build the water pipeline.

If the Great Water Alliance isn’t, strictly speaking, an actual partnership, it does represent a hope that all of these communities can come to feel like a part of something bigger than themselves.

“Normally you’re thinking of naming a service or a product or something that’s in a box, or a company,” McSweeney said. But he added that it’s not unheard of for officials to apply the logic of marketing to a large public-works project.

However unsexy infrastructure may be, big projects have an important place in the public mind — think the Chunnel connecting Great Britain and France, or Boston’s problem-ridden and much-maligned Big Dig. Earlier in his career, McSweeney did PR work for several major environmental restoration projects in Florida. He also points to Wisconsin-specific examples in Milwaukee like the Zoo Interchange in Milwaukee.

In developing the Great Lakes Alliance concept, MSK conducted focus groups with residents from Waukesha and the “allied” communities, focusing on people who participated in previous public meetings about the project rather than local officials. About 110 people took part in these focus groups, McSweeney noted.

“Some people had great knowledge of the program and what it was all about. Some people had info but it wasn’t exactly correct…. but what we found was overall there was support,” he said.

Cheryl Nenn of environmental group Milwaukee Riverkeeper has consistently opposed the Waukesha project, but sees the sense of having a centralized website that people can consult for information. Some of its information will include scientific data about water flow and quality, but the presentation is still Waukesha’s to shape. She says it might be hard for someone visiting the website to figure out who exactly the Alliance is or what its goals are. But if those goals include more community engagement, Nenn seems happy to provide some.

“We’re planning to watchdog the whole process to make sure the project is meeting all the Compact requirements,” Nenn said. “The [Great Water Alliance] website has a very kind of glass-half-full interpretation to return flow and other issues.”

Duchniak said the audience for the website extends to people throughout the Great Lakes region, in eight states and the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec, many of whom know Waukesha’s bid for Lake Michigan’s water sets a precedent for other communities that might seek to tap the lakes in the future.

“This really hasn’t been your normal public works project,” Duchniak said. “We’re well aware that there’s a lot of people watching it.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us