Struggling Through A 21st Century Flu Season With 1940s Science

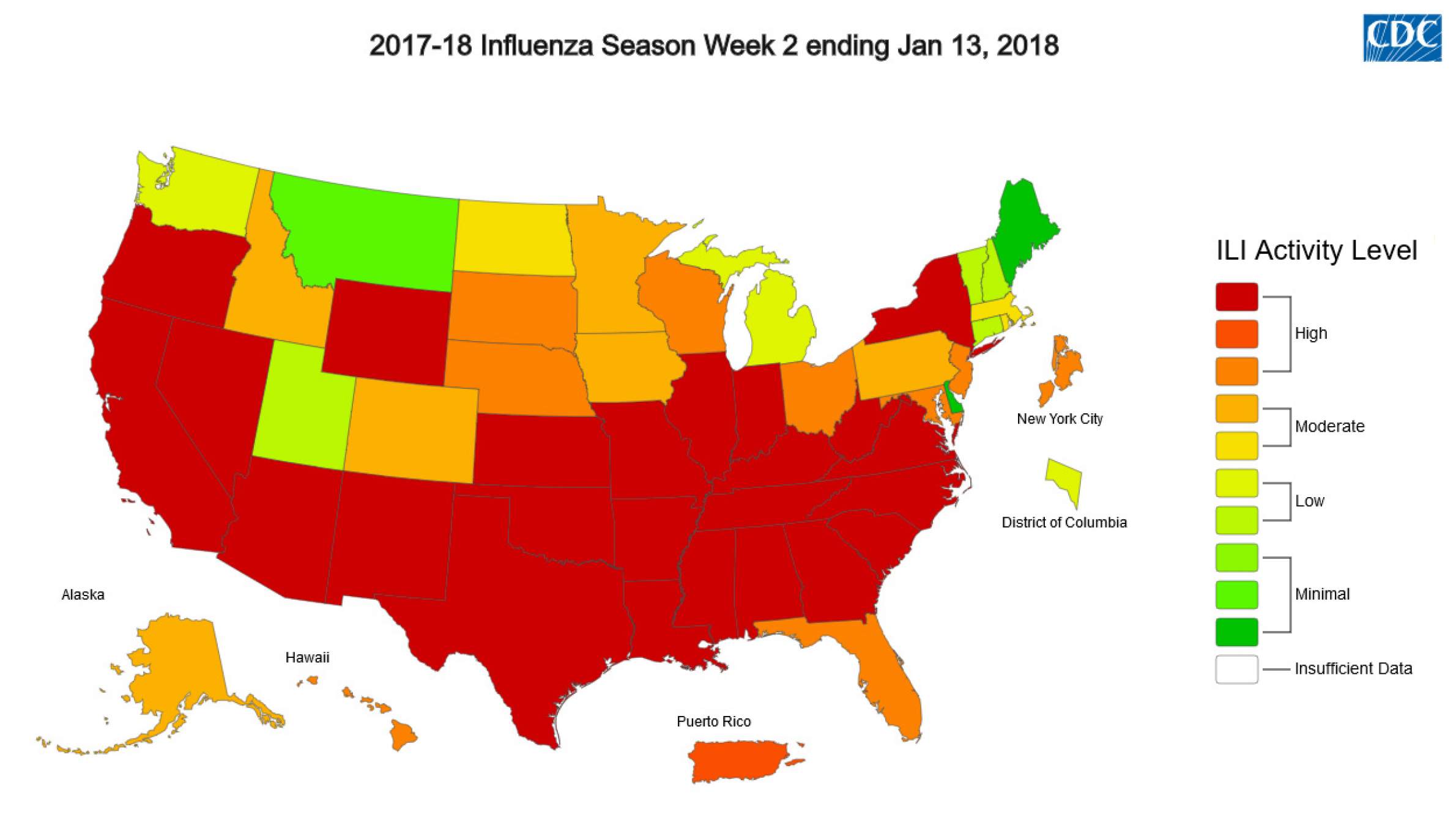

The 2017-18 influenza season is well underway across the United States, and it's proving to be a rough one.

January 25, 2018

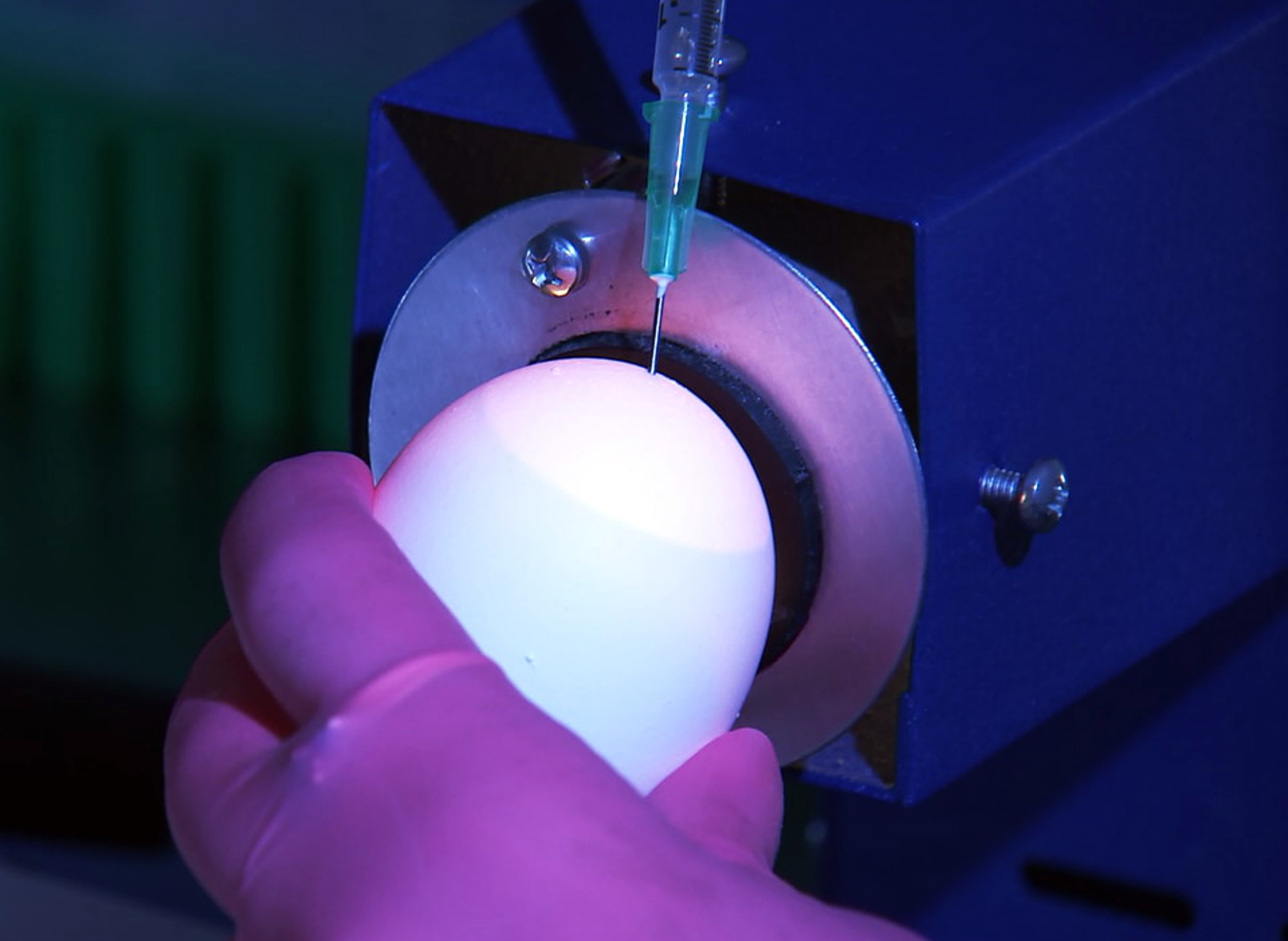

CDC scientist mixing influenza samples

The 2017-18 influenza season is well underway across the United States, and it’s proving to be a rough one. The season’s vaccine has been found to be relatively ineffective — though it’s still recommended to get one — with hospitals in some places filling up with sick patients and facing medicine shortages.

In Wisconsin, influenza activity has jumped from moderate to high levels, based on reporting issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Jan. 19, 2018. While hospitals around the state have yet to reach their capacity, the strain on resources has not gone unnoticed and conditions are more likely to get worse before improving, the state Division of Public Health’s influenza coordinator told Wisconsin Public Radio.

As bad as this flu season may be, epidemiologist Dr. Michael Osterholm said the 2017-18 season is far from the most severe the U.S. has seen. Understanding the context behind one season’s flu outbreak and those that have become full-blown pandemics in decades past is a key part of fighting the virus. As director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, Osterholm argues that one of the best ways to combat influenza and prevent a global pandemic is through a comprehensive vaccine.

In a Jan. 24, 2018 interview with WPR’s The Morning Show, Osterholm broke down the factors at play in this year’s flu virus and the necessary steps to combat the flu in the future.

“Seasonal flu is a reality, it happens every year,” Osterholm said. “Some years are a bit worse than others and it depends on which strain of the flu virus is circulating. This year, while it is not a good year, it’s actually not a really bad year either.”

The dominant strain of the flu in 2017-18 is caused by the H3N2 subtype of the influenza A virus, a variant that can have particularly devastating outcomes on young children and the elderly.

Flu symptoms include muscle ache, fever and malaise, and typically last between one to five days. However Osterholm explained that its symptoms are not as wide ranging as is often believed. For example, influenza generally does not affect the intestines or cause a cough. These symptoms are caused by secondary infections, like pneumonia, which are ultimately what lead to to an influenza infection becoming deadly.

Another way that the flu can become deadly is through what Osterholm described as “an overactive immune system.” This outcome is more typical among younger patients and can be particularly deadly. Symptoms of this reaction typically result in non-responsiveness in a patient.

In Wisconsin, older adults are being particularly affected by the H3N2 virus. Of the 2,500 flu-related hospitalizations in Wisconsin since September, some 70 percent have been of those 65 and older, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported.

Having the flu generally feels “like you’ve been hit by a truck,” Osterholm said. Influenza is a highly infectious virus, a 2018 study confirmed that it has the ability to spread simply through breathing.

Developing annual vaccines

Variants of the influenza virus exist throughout the year, circulating through tropical regions and able to make their way around the globe, Osterholm explained.

In a given year, the flu vaccine can be between 10-60 percent effective, he said. This limitation exists because public health officials must make what is essentially an educated guess at what that season’s flu strains are likely to be each year. There are 18 different variations of the “H” determinant of the flu, which is shorthand for the type of hemagglutinin, a protein, that’s present on the virus surface. The strains that generally infect humans are H1, H2, H3, H5, H7 and H9 — the 2009 swine flu pandemic was caused by the H1N1 variant.

When public health officials and researchers talk about creating a “universal” flu vaccine, they mean one that would cover all six H variants. Osterholm said the world “universal” is a bit misleading, and recommended using a term like “game-changing” instead. However, he also added that influenza research is far from a priority when it comes to the allocation of health research funding. It received roughly $32 million in 2018, compared to the $1 billion that HIV vaccine research receives annually.

When it comes to treating the flu, Osterholm explained it is important to distinguish the difference between “pandemic” and “seasonal” flu viruses. A flu pandemic results when a new strain of the virus is transmitted from animal hosts and genetically adapts in a way that can infect humans. Such a virus will move around the globe, infecting people regardless of the time of year, and spread rapidly because people have no immunity to it. Seasonal flu, on the other hand, is a particular strain of influenza that has become part of the virus mix that occurs from year to year. This is is the type of influenza that scientists can try to anticipate with vaccines.

Influenza vaccines are most commonly produced by creating viral cultures in chicken eggs. This process partially explains why the 2017-18 flu has been so tricky to prevent, as it’s more difficult to cultivate H3 strains in eggs. Moreover, scientists have found that that the influenza virus can adapt to the egg environment, reducing its effectiveness. In recent years, researchers and manufacturers have turned to growing the flu virus in cell cultures rather than eggs, but this process remains slow and arduous.

Unprepared for a flu a pandemic

Investment in influenza research took off during World War II, Osterholm told The Morning Show. This interest was largely because people were terrified of another pandemic similar to that which struck around the globe at the tail end of World War I. The 1918 flu pandemic killed 100 million people worldwide; a century later, accounting for population growth, an equivalent toll would be about 400 million deaths.

The medical advancements that have been made since the flu vaccine was first made available in the 1930s are minimal, Osterholm explained. The vaccines used to prevent the flu in the 21st century often “leave us a day late and a dollar short,” he said. It would take billions of dollars and a global commitment to make necessary advances with influenza virus research and create a “game-changing” vaccine. And when it comes to treating any future pandemic, humans are in trouble, he added.

“We are not prepared,” Osterholm wrote in a New York Times op-ed published Jan. 8. “Our current vaccines are based on 1940s research. Deploying them against a severe global pandemic would be equivalent to trying to stop an advancing battle tank with a single rifle. Limited global manufacturing capacity combined with the five to six months it takes to make these vaccines mean many people would never even have a chance to be vaccinated. Little is being done to aggressively change this unacceptable situation. We will have worldwide flu pandemics. Only their severity is unknown.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us