Sidelined By Headaches, Former Badger Plans To Sue NCAA Over Brain Injury Risk

At 6 feet tall and 195 pounds, Tony Megna was considered too small to be a college football linebacker. Megna was determined, though, to play for the University of Wisconsin-Madison squad.

May 20, 2018

Tony Megna football illustration

At 6 feet tall and 195 pounds, Tony Megna was considered too small to be a college football linebacker. Megna was determined, though, to play for the University of Wisconsin-Madison squad.

As a walk-on in 2007, Megna said, he was expected to work harder than his peers on the field and at practice. There was no scholarship to help pay for college, and his odds of making it to the NFL were low, so Megna said he went beyond what he thought were his physical limits.

His attitude was, “You’re playing NCAA football. You’re a warrior.”

Megna said he knew he was putting his body on the line for the game but, “I wasn’t aware of brain injury.”

Disturbed by what he has learned since his football career ended, Megna is now planning legal action. He intends to join a group of former college football players who have filed 111 lawsuits to date seeking to create a class action against the NCAA and its athletic conferences.

His attorney, Jeff Raizner of Houston, said there is a “high likelihood” Megna will be a plaintiff in the case, which is months, if not years, away from trial. If filed, Megna’s claim could become the first to pull UW-Madison into the litigation.

The suits, which were moved to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois in 2016, are seeking compensation for medical bills, lost income and reduced future earnings related to brain injuries from playing college football. According to the lawsuits, the NCAA has known about the dangers of brain injuries for more than 80 years.

Megna estimates he racked up between $15,000 and $20,000 in medical expenses — such as acupuncture, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, chiropractic treatments and travel — over the past eight years related to head injuries.

The NCAA has filed motions to dismiss the claims on the grounds that the former players have not brought forth “a claim upon which relief can be granted.” The NCAA also argues that the statute of limitations has run out — an argument the plaintiffs’ attorneys dispute.

The organization declined to respond to questions for this story, including whether it felt an obligation to pay for medical expenses of former college athletes suffering from ailments connected to their playing days. The UW Athletic Department also declined to comment.

‘I couldn’t do it anymore’

Tony Megna said that he began suffering severe, chronic headaches in the off-season before his junior year, forcing him to miss most of the 2009 season. The Oak Creek native then turned to medical staff, neurologists and doctors specializing in headaches.

Megna said he found few answers about the cause of the headaches that swept over him up to 30 times a day.

“None of them ever said ‘Oh well you’re getting headaches because you’re getting hit in the head 100 times a week, you’re playing a contact sport, so it’s a direct result from playing your sport,” Megna said. “Their big thing was that if you could play with the pain, then you’re cleared to play.”

Instead, he was given medication to reduce inflammation and mask the pain. It never did. Megna said he was never told he might need to step away from the sport.

That decision came from Megna. He left the team before his junior year but returned at the team’s request as a backup to Chris Borland, who just six years later walked away from a multimillion-dollar contract with the San Francisco 49ers over concerns about head injuries. Borland now is a national figure in a campaign to raise awareness about sports-related brain injuries.

“It was getting to the point,” Megna said, “where I couldn’t get through practice without throwing up. I couldn’t concentrate in school. I almost flunked out a semester because of poor concentration, couldn’t remember things, short-term memory loss. It was very much a decision of I couldn’t do it anymore.”

Megna’s father, Mark, remembers watching his son struggle to keep going.

“It was just an unbelievable situation that none of the doctors could figure out what was going on. They didn’t restrict him from playing,” Mark Megna said. “I mean, he hit every day in practice like everybody else. It was gut-wrenching to watch. I mean he literally almost died playing.”

Earlier this year, the NCAA’s major conferences approved a program that guarantees medical treatment for athletic injuries for at least two years after the athlete leaves the sport.

Philadelphia attorney Sol Weiss, the co-lead counsel for the former players, said the NCAA needs to get more serious about current and former athletes’ safety.

“For decades, the NCAA has failed to protect and educate those in its care on the risks associated with college football,” Weiss said in an interview. “Even to this day, the NCAA does not have a mandatory uniform concussion protocol in place to protect college football players.”

But according to Joshua Gordon, an instructor in sports business and law at the University of Oregon, the lawsuits are unlikely to bring about a “systemic, tide change” for the NCAA.

Gordon said the result will likely depend on the facts of each player’s case and the jurisdiction where he played. Programs that showed a blatant disregard for their student-athletes’ health would be most vulnerable, he said. The result could be narrow, case-specific rulings, Gordon said.

According to Gordon, the bigger impact may be on public opinion.

“There’s an overall theme developing that the NCAA doesn’t care about student athletes and that the NCAA is not about academic missions or any of that,” he said. “I think the NCAA is absolutely vulnerable, and the NCAA needs to pay attention and find a way to get in front of some of these issues.”

Former football players sue

There are currently 111 lawsuits filed against the NCAA, each covering one or more former players alleging brain injuries from playing football. The claims against the collegiate sports organization and its conferences, which include negligence and breach of contract, are brought by those who played football as far back as 1952. The plaintiffs are demanding medical care to cover former athletes for symptoms that persist or develop years later, lost earnings and other damages.

Four cases have been chosen to represent other plaintiffs so District Judge John Lee can determine if the court will certify the class and what restrictions to place on it. Raizner said Megna’s case would likely move forward after the four sample cases have been litigated. Megna would have the option to become a single plaintiff or file a class-action lawsuit which would cover all former UW football players, he said.

The four sample cases and possible class certification will be ruled on in 2019 or 2020, based on the court’s scheduling order. They are:

- Eric Weston, who was a defensive end at Weber State in Utah from 1996 to 1997. He sometimes could not remember the games he had just played.

- Jamie Richardson, a wide receiver at the University of Florida from 1994 to 1996. He said he was put back into games despite being concussed.

- Michael Rose and Timothy Stratton, who played for Purdue University in the late 1990s. Rose, a linebacker, suffers from ailments including uncontrollable mood swings. Stratton, a tight end, claims he is plagued by anxiety, anger and depression. “While the players competed and the fans cheered for more, defendants Big Ten and the NCAA kept critical information in the dark concerning an epidemic that was slowly injuring and killing their student-athletes,” according to the Rose and Stratton complaint.

- Zack Langston, a linebacker at Pittsburg State University in Kansas from 2007 to 2010. Wracked by paranoia, memory loss and stress, in 2014, Langston shot himself in the chest. He wanted his brain to be preserved for research. An autopsy determined he had been suffering from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the degenerative neurological brain disease which has been linked to repeated blows to the head. He was 26.

Career ended but symptoms endure

When he left the team and left the sport, Tony Megna lost the medical care he received as a student athlete. As the symptoms persisted, Megna sought out medical advice on his own.

He said he suffered from major periods of depression, bouts of anxiety and suicidal thoughts — all symptoms associated with trauma and potentially CTE. The disease has been shown to induce symptoms that range from mild, such as impaired judgment and mood swings, to aggressive, such as increased risk of suicide, Parkinson’s and dementia.

Megna said he still suffers from occasional headaches, but they are not as severe as they once were.

“Research suggests that I will have dementia by the time I am 40 or 50,” said Megna, now 29. “So that is the risk of playing competitive football. So I guess that has become my life work — to make sure that does not happen.”

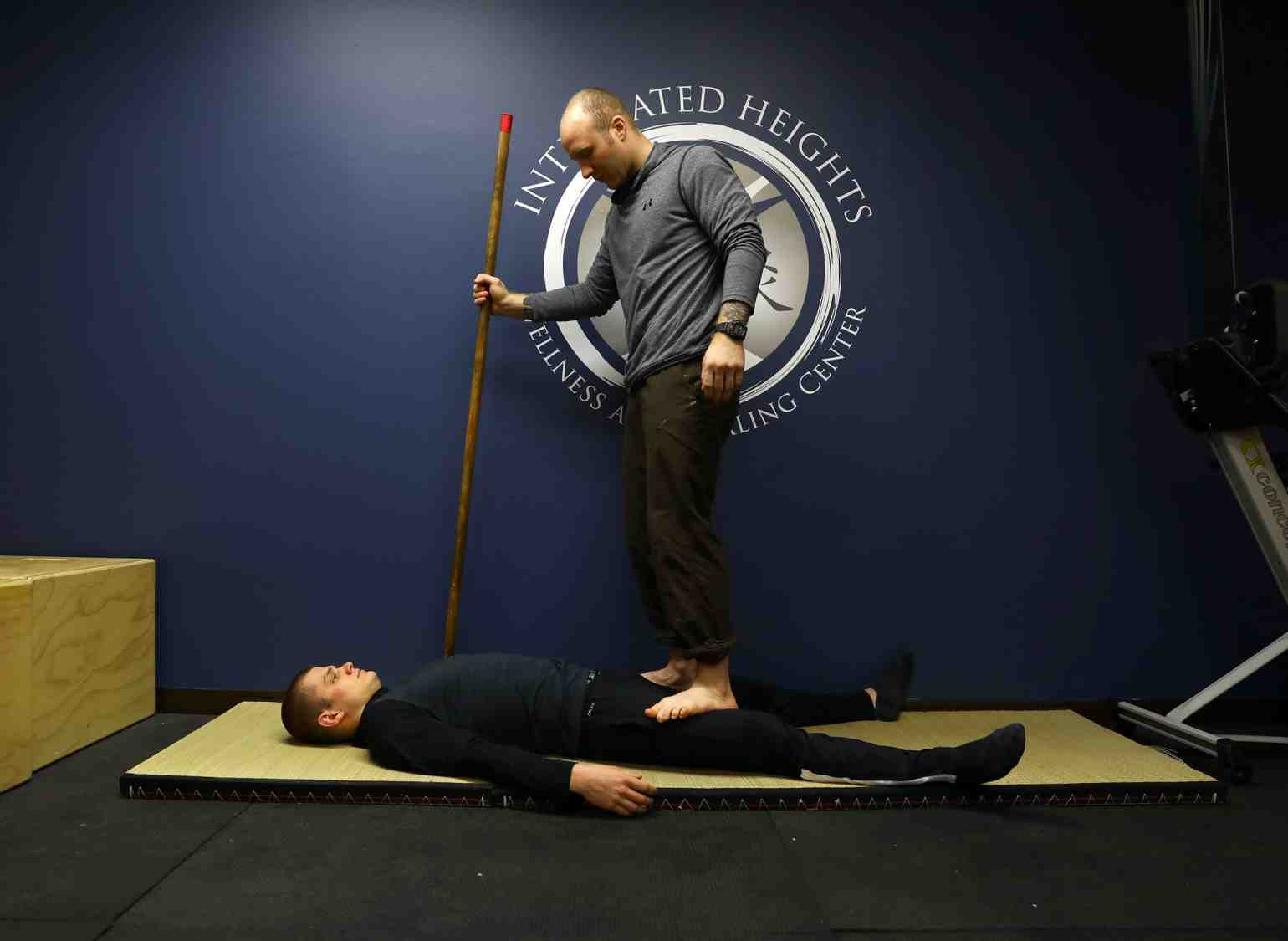

In his journey to find answers about his own health problems, he turned to nontraditional medicine, including acupuncture. Due to the fact he “wasn’t getting hit in the head while trying to learn,” Megna was able to graduate from the Midwest College of Oriental Medicine in Racine with a master’s degree in traditional East Asian medicine. He owns Integrated Heights Wellness and Healing Center in Mount Pleasant.

On a recent afternoon in Megna’s clinic, he demonstrated techniques that he uses to treat a number of ailments including concussion on a semi-pro football player. Megna used forceful massages to direct blood flow to certain areas and acupuncture needles placed in various locations on the body. He walked on the patient’s back and core to strengthen those regions, and used assisted stretching on the athlete’s legs and arms.

In a video produced by the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism, Megna describes his experiences playing college football, coping with brain injury and his “life’s work to make sure I don’t get dementia, that I don’t lose my mind.”

Megna believes injured athletes should be given longer recovery times and that the NCAA and NFL need to do more to prevent, rather than merely react to, repeated blows to the head.

“I don’t think they are doing enough as far as recovery of the brain. They aren’t proactive enough,” Megna said.

NCAA moves not enough, some say

The season after Tony Megna left the Badgers team, the NCAA instituted the Concussion Management Plan, requiring every school to have a protocol in place to help prevent and treat head trauma. One of the most important aspects of the protocols is injury education.

The NCAA requires players to sign waivers at the beginning of each season after receiving the mandated concussion education. For example, the Big Ten Conference form requires athletes to agree that “I have the direct responsibility for reporting all of my injuries and illnesses to the sports medicine staff.”

Johna Register-Mihalik, an assistant professor of exercise and sport science at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, said the provision has an obvious problem: “asking people who are cognitively impaired to make good cognitive decisions.”

Symptoms for concussion include confusion, concentration and memory problems, according to the NCAA fact sheet handed out to athletes.

Register-Mihalik noted the requirement asks athletes to “make a pretty difficult and complicated decision” at a time when their “executive function,” or impulse control, is impaired.

The litigation that Megna plans to join is a follow-up to a 2013 class action lawsuit brought by current and former athletes that resulted in a settlement mandating that the NCAA set up a $70 million medical monitoring program for college athletes plus $5 million for concussion research.

The 50-year monitoring program allows former athletes to receive a maximum of two medical evaluations. The program does not include treatment. And medical tests are granted at the discretion of the NCAA’s newly formed Medical Science Committee.

Gordon said many cases against the NCAA over concussions suffered by athletes have settled out of court, as did the 2013 lawsuit. If the goal is “systemic change,” he said, “a settlement won’t do anything.”

End of football?

Tony Megna knows what it takes to be successful at football. It is also what makes the sport so dangerous.

“You become animalistic, you go crazy. You just have no fear. You just have to put your body on the line. Your mind becomes primitive in that place. You do what you have to do,” Megna said. “You become numb to the pain.

“We are taught to tough it out,” he continued. “That is part of the territory. Certainly, if you voice too much … they’ll look to that other person who is reliable who can do a little more.”

Can football — a multi-billion dollar sport which millions of Americans have come to love — coexist with player safety?

According to Mark Megna: Probably not.

“It’s one of the only employers that is purposely putting their employees in harm’s way,” said the elder Megna, who is a corporate executive at Doral Corp. in Oak Creek. “You could never put your employees in harm’s way, [but] … this is just done as part of the game. So it’s unbelievable because it can’t change. Because that is the game.”

Tony Megna acknowledges he would do it all over again. Learning to overcome the pain and setbacks he endured is something he probably would not have learned without football.

His father, however, is not sure it was all worth it.

“We don’t know what long-term symptoms can be with something so complex as the brain,” Mark Megna said. “You hear stories of NFL players and college players’ recurring effects that go on their entire life.”

Luke Schaetzel, a recent University of Wisconsin-Madison journalism graduate, is a freelance reporter based in Madison. Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism managing editor Dee J. Hall contributed to this report. The nonprofit Center collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates. The Center’s collaborations with journalism students are funded in part by the Ira and Ineva Reilly Baldwin Wisconsin Idea Endowment at UW-Madison.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us