What's Next For The Math At The Heart Of Wisconsin's Redistricting Lawsuit

When the Supreme Court of the United States returned a closely-followed case on redistricting in Wisconsin to a lower court, the majority's decision suggested that they did not completely accept a specific metric of gerrymandering known as the efficiency gap.

June 28, 2018

Wisconsin Assembly District 76 outline illustration

When the Supreme Court of the United States returned a closely-followed case on redistricting in Wisconsin to a lower court, the majority’s decision suggested that they did not completely accept a specific metric of gerrymandering known as the efficiency gap. However, this action also suggested that a majority of the justices are interested in figuring out how to address the issue of partisan gerrymandering.

The court ruled on June 18, 2018 that plaintiffs in Gill v. Whitford did not establish that they had been personally and directly injured by the Wisconsin Legislature’s 2011 Assembly district map, and therefore had no legal standing to bring the case to the Court. Federal courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court, only have jurisdiction in cases where the plaintiff can show that they suffered direct personal injury due to the conduct of the defendant and that they have “a personal stake in the outcome of the controversy.”

The plaintiffs in Gill v. Whitford argued that they suffered personal injury from partisan gerrymandering in the form of dilution of their votes for partisan candidates. This dilution was achieved, argued the plaintiffs, by two processes that are used to accomplish partisan gerrymandering during a redistricting process: cracking and packing geographic clusters of voters for the opposing party.

Cracking refers to the practice of drawing district boundaries in such a way that geographic clusters of votes for one party’s candidates are divided across multiple districts, making it hard for them to win representation in any.

Packing, on the other hand, refers to drawing boundaries in such a way as to cram as many votes for a party as possible into a single district. This practice makes it very easy for the packed party voters to win representation in that district, but effectively keeps its voters out of neighboring districts, making it easier for the majority party to preserve its majority in a legislature as a whole.

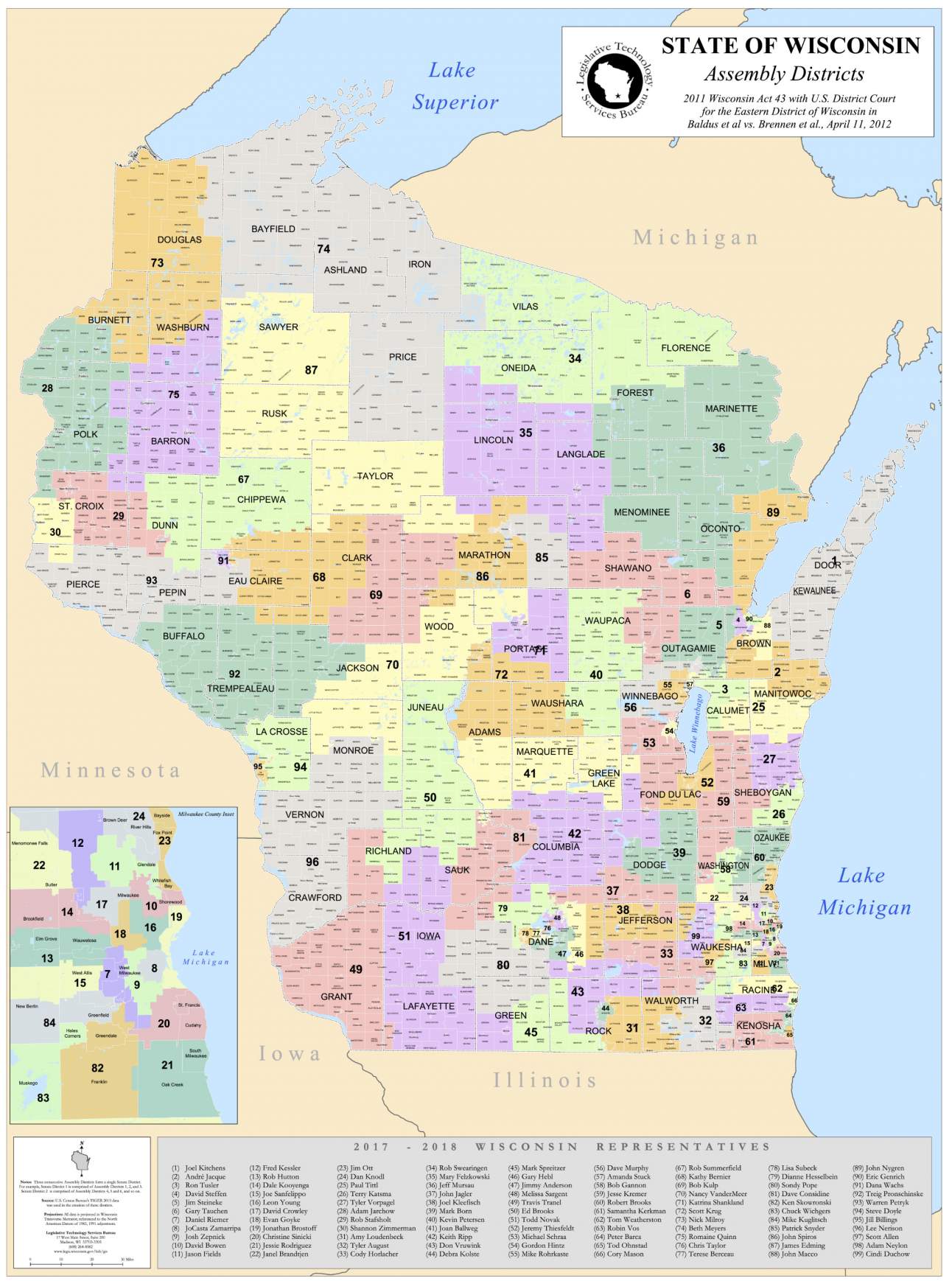

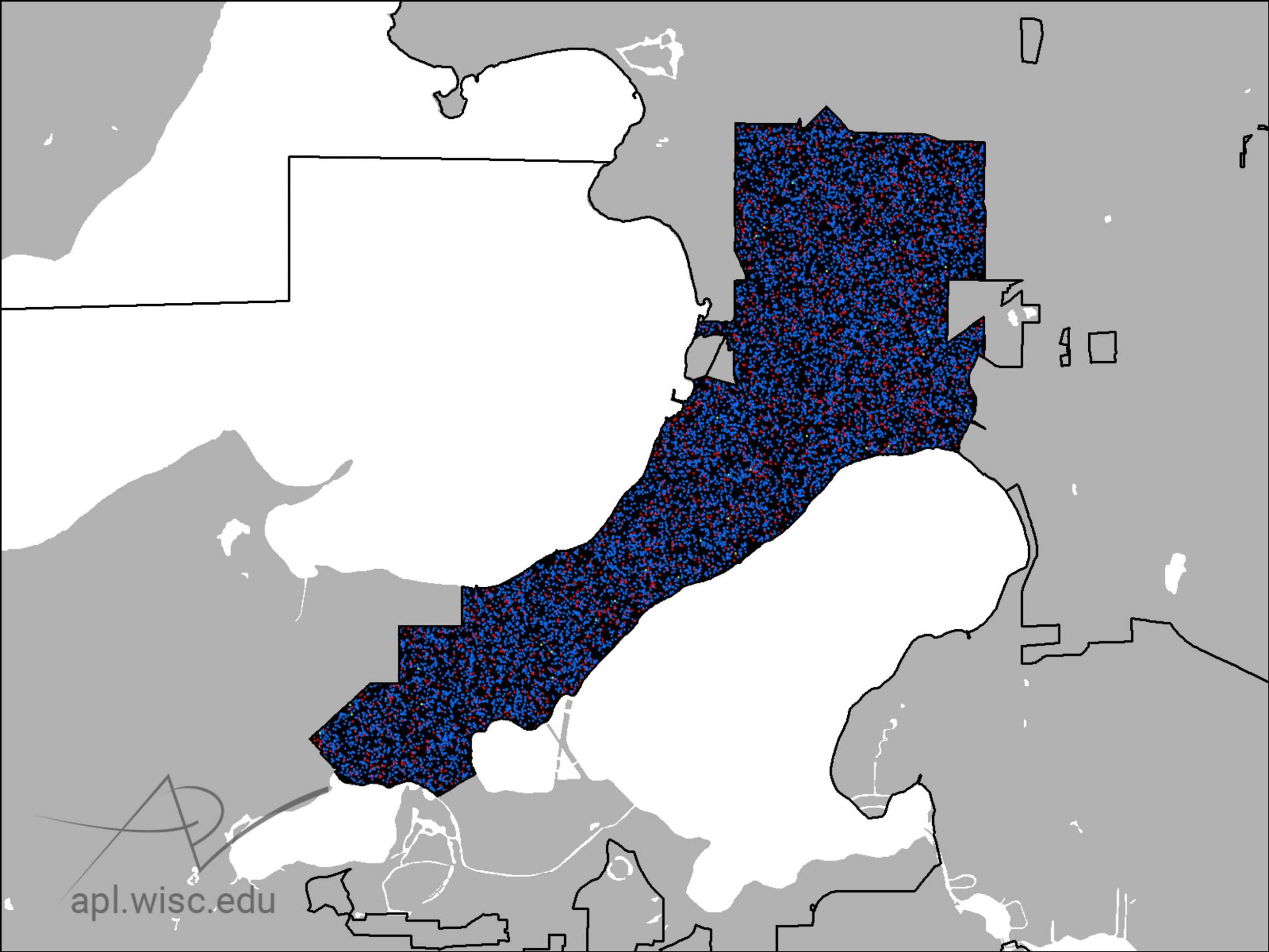

In Wisconsin, the plaintiffs argued that the Republican-controlled statehouse pursued partisan gerrymandering when it controlled the decennial redistricting process in 2011. The patterns of cracking and packing can be examined in the Assembly districts around the Milwaukee region, particularly when compared with the previous set of maps devised in 2001.

Calculating the efficiency gap

During oral arguments in October 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court heard several types of arguments that a dilution of the plaintiffs’ votes had occurred following adoption of the 2011 district map. The primary evidence was a measure called the efficiency gap. “Efficiency” refers to how efficiently a political party can turn its votes into representation across multiple legislative districts, with as few “wasted votes” as possible.

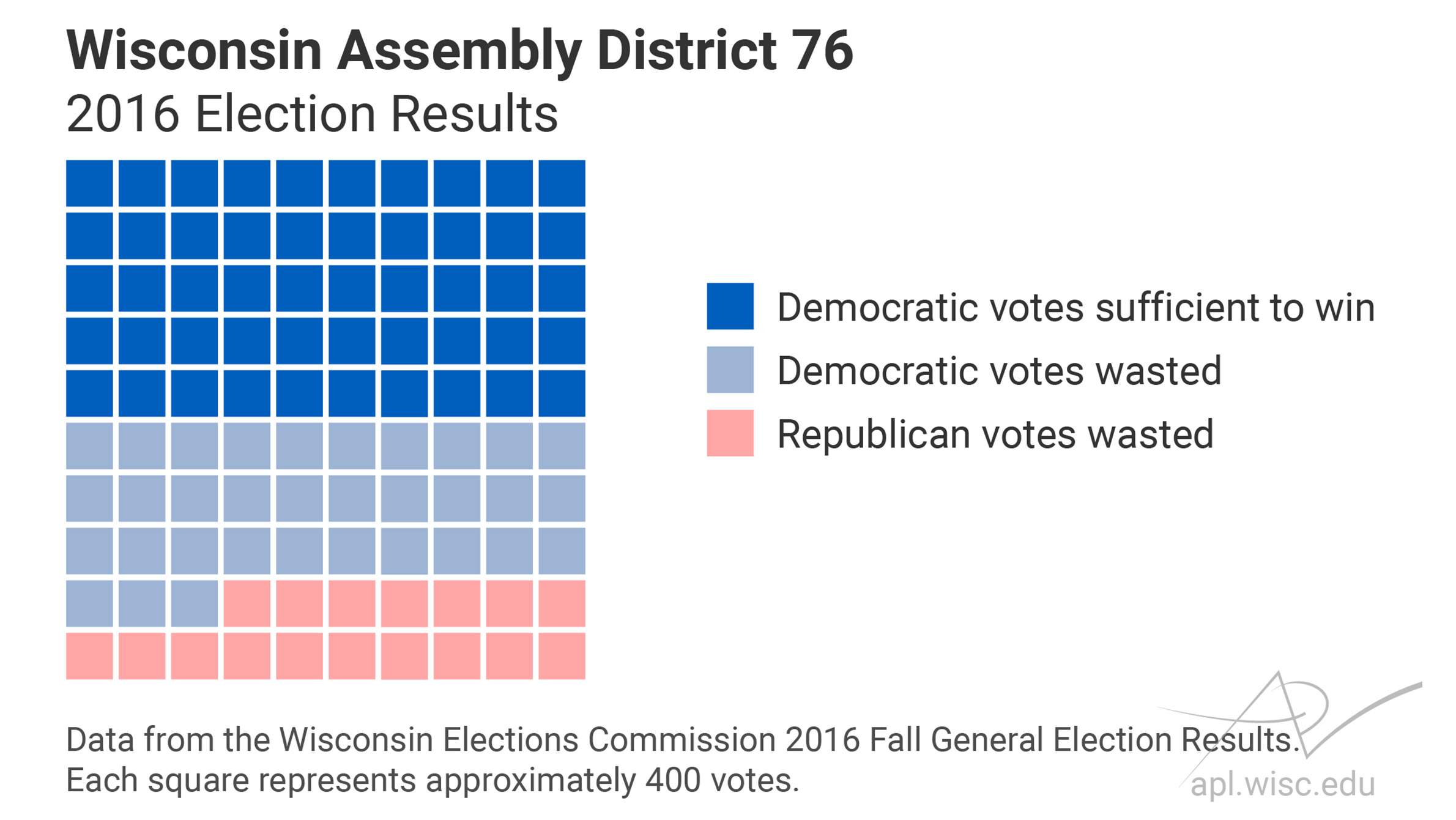

To calculate the efficiency gap for a state legislature, two kinds of voting outcomes are important within each district: all the votes for the losing candidate, and all the votes for the winner in excess of the exact number needed to win the seat in a given election — half of all the votes cast plus one vote. Third party votes are ignored in this calculation.

Using the November 2016 election results for the Wisconsin Assembly’s District 76 as an example, it’s a definitively “blue” district where the Democratic incumbent Chris Taylor won a decisive victory with 33,628 votes. In comparison, Republican candidate Jon Rygiewicz received 6,877 votes. The district is located in central Madison, and is among the most Democratic-leaning in the state.

All 6,877 votes for Rygiewicz would be considered “wasted” for District 76 because they didn’t produce a win. In addition, since Taylor only needed 20,253 votes in that election to win the district, the remaining 13,375 votes she received were wasted too. That is to say, Taylor would have still won if all those votes had been cast for her opponent. In District 76, even though Taylor won, there were a lot more Democratic votes wasted than Republican votes — 6,498 more votes, to be exact.

To calculate the efficiency gap for a state as a whole, the wasted votes are added up across all districts to find how many wasted votes there were by party statewide. For whichever party wasted more votes, their total wasted votes is then divided by the total number of votes cast statewide, giving the percent of all votes wasted by party. That figure is considered the efficiency gap. A proposed standard is that an efficiency gap of about 8 percent or more is evidence of purposeful manipulation of the districts. Based on 2016 election results for the Assembly, Wisconsin’s efficiency gap was calculated to be 10 percent in the 2016 fall general election, favoring the GOP. This is a substantially larger efficiency gap compared to analysis of pre-2011 elections.

The efficiency gap is often also compared to the Assembly’s partisan mix. After the 2016 elections, Republicans held 64 out of 99 seats, or 65 percent of the total. Republican candidates received 52 percent of the vote in contested races, though.

Another way to look at this difference is to note that with an efficiency gap of zero, based on how the votes were cast alone, Republican candidates would have been expected to win about 52 seats in the Assembly. In the actual election, though, Republicans were able to pick up 12 more seats. However, equal levels of wasted votes between two parties is an unrealistic standard — in any election, of course some votes will be cast for candidates who lose. The question among researchers who are trying to quantify gerrymandering is identifying an imbalance in the number of wasted votes by one party or the other.

The efficiency gap is a measure that can only be calculated for balance of power in a legislature as a whole. It cannot be calculated for any individual district. So although the 2016 election results for Wisconsin Assembly District 76 are public record, it doesn’t make sense to ask what is the efficiency gap for that specific district, or any other. The efficiency gap is a measure of the sum of many parts.

The future of the efficiency gap metric

The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision stated that the plaintiffs must show dilution of their votes — that is, the harm they’re alleging — that is district-specific.

“An individual voter in Wisconsin is placed in a single district,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts. “He votes for a single representative. The boundaries of the district, and the composition of its voters, determine whether and to what extent a particular voter is packed or cracked. A plaintiff who complains of gerrymandering, but who does not live in a gerrymandered district, ‘assert[s] only a generalized grievance against governmental conduct of which he or she does not approve.’ United States v. Hays, 515 U. S. 737, 745.”

In his decision, Roberts specifically called out lead plaintiff William Whitford as an example of how the majority found that legal standing had not been sufficiently established.

Whitford lives in District 76 in Madison — a district that leans so Democratic that “under any plausible circumstances,” it would be represented by an Assemblyperson from that party. In essence, Roberts wrote that it wouldn’t matter if the districts were drawn differently, as the outcome in that district would be the same and therefore Whitford did not have a personal stake in the outcome of the case. In other words, Whitford could not have been personally harmed in terms of dilution of his vote by the way his own district was drawn.

The Court rejected arguments that a gap between a statewide Democratic majority among voters and a Republican majority of state Assembly representatives could be interpreted as specific, personal injury to a Democratic voter who was represented by a Democratic legislator in a heavily Democratic district.

The fact that the Court’s decision was based on standing indicates that the justices did not accept that gerrymandering is a process that occurs simultaneously in all districts, but is rather exhibited in each district individually. By implication, that line of thinking suggests that they did not accept arguments that the efficiency gap can measure partisan gerrymandering.

However, to state that living in a packed district and having been affected by partisan gerrymandering are inconsistent with one another ignores the fact that every acre of Wisconsin must be located in one and only one Assembly district, as well as the fact that the 99 districts of the chamber are drawn simultaneously in a single process. Districts are not drawn independently of one another, and do not exist independent of one another. Indeed, cracking and packing are achieved by creating a particular dynamic between districts.

In short, partisan gerrymandering is by definition something that happens between districts, not within individual districts. The court’s decision suggests they needed additional evidence that a district map could harm all voters in the state for a particular party, and not just those whose candidates lost their races.

So what’s next for the Wisconsin Assembly? For now, the 2011 district map stands. The case will go back to the lower court, where the plaintiffs will have the chance to prove “concrete and particularized injuries” to their votes. It’s likely that the plaintiffs will present different metrics of gerrymandering with more emphasis on how individual districts add up next time around, as well as additional plaintiffs — perhaps one from every district in the state. The fact that the U.S. Supreme Court remanded the case to give the plaintiffs the opportunity to establish standing suggests that the 7-2 majority of justices believed such cases as Gill v. Whitford can be resolved.

If the Court thought standing could not be established, they would have decided to dismiss the case instead of remanding it, which was the opinion of dissenting Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch. However, Justice Anthony Kennedy’s vote was considered pivotal in all recent rulings on gerrymandering, including this case — his retirement could affect the balance of power in Court and will affect future decisions on this case.

Meanwhile, the 2020 U.S. Census will refresh the total population count, and shortly thereafter the usual decennial redistricting process will take place. Unless there is a dramatic change in the state laws governing the redistricting process before that point, new Wisconsin Legislature district maps will be drafted and passed into law like any other state legislation. They require a majority vote from the Assembly and state Senate, and the signature of the governor. Meanwhile, rapidly emerging computing and data advances are making it easier and more accessible to predict how voters will behave at the polls — putting the tools to achieve gerrymandering at the fingertips of those who draw the maps.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us