What Happened To Wisconsin's Once-Thriving Smaller Jewish Communities?

Jews living in prosperous small-town communities in the mid-20th century saw large population declines over several decades as the next generation favored the opportunities that larger cities presented.

September 25, 2019

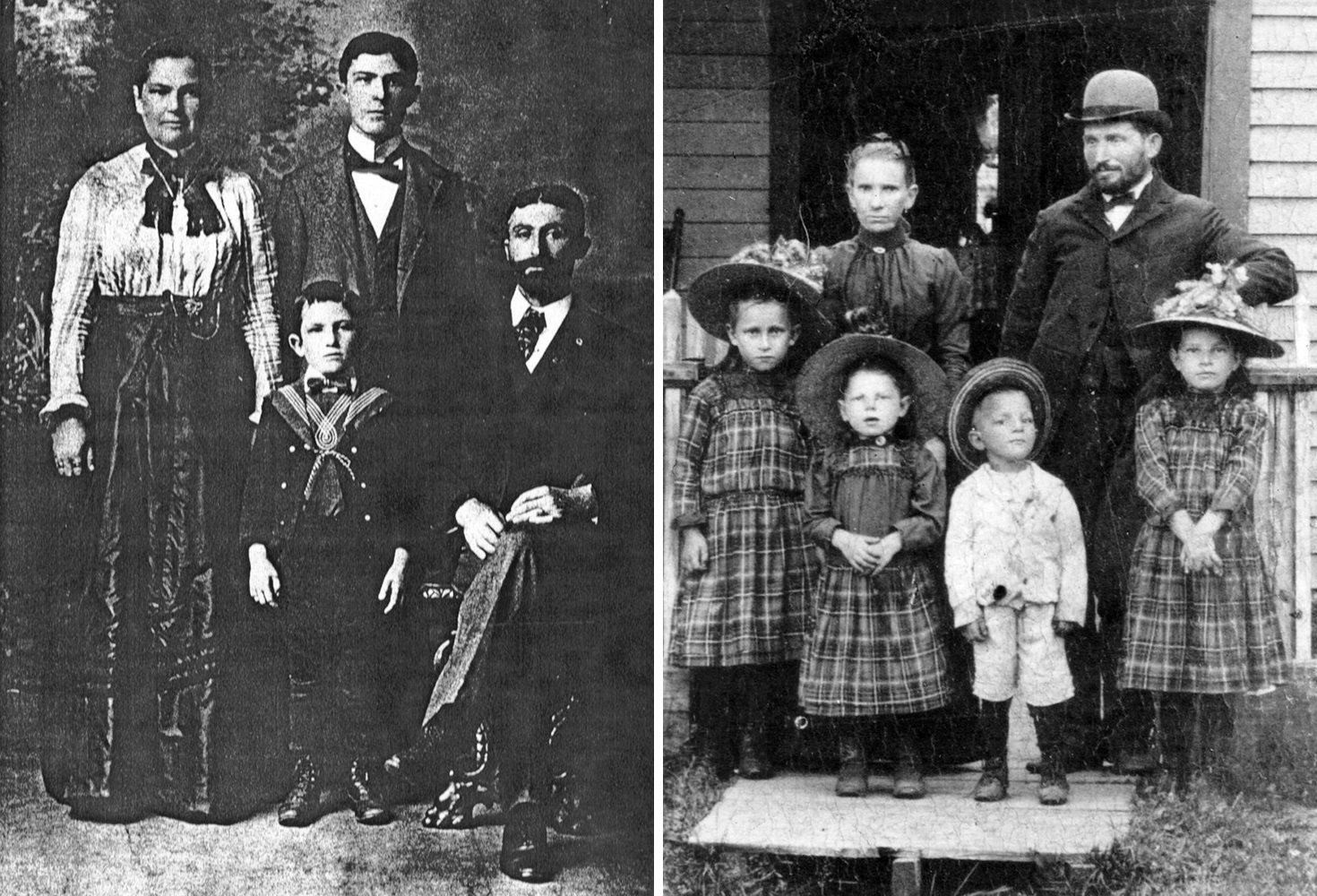

Stained glass window at Beth Hillel Temple in Kenosha

Jews who immigrated to the United States did not share one common homeland, unlike most other newcomers. Instead, their community ties centered on shared history, sets of traditions and cultural values. Jewish immigrants started settling in Wisconsin in the state’s earliest days, but the largest waves of immigration began in the late 1800s and stretched into the first two decades of the next century. Initially largely from Germany, they increasingly hailed from Poland, Russia and other countries around central and eastern Europe. Upon arriving in Wisconsin, Jews settled around the state, significantly in Milwaukee but also elsewhere, in cities, small towns and rural areas. In the 2016 book Jews In Wisconsin, published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press as part of its People of Wisconsin series, author Sheila Terman Cohen recounts the Jewish experience in the state. An excerpt from the book examines how Jews living in prosperous small-town communities in the mid-20th century saw large population declines over several decades as the next generation favored the opportunities that larger cities presented. Meanwhile, the Jewish communities in mid-century Milwaukee and Madison expanded and flourished, growing in religious diversity, establishing vital and lasting businesses and engaging in civic service work to support refugees, the indigent and the elderly.

The rise and fall of small-town Jewish communities

Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance, you must keep moving. —Albert Einstein

The postwar era of prosperity in Wisconsin and throughout the nation from 1945 to 1964 resulted in a skyrocketing national birth rate, later referred to as the Baby Boom. With more disposable income, families built new homes and formed new neighborhoods in the suburbs. Small towns of Wisconsin flourished, and Jewish communities prospered with new homes, synagogues and successful businesses in those areas throughout the 1940s.

However, these same Jewish communities began to decline in the 1950, ’60s and ’70s as larger cities and higher education beckoned the next generation. As the postwar period gave rise to the GI Bill, which granted World War II veterans money to further their education, college enrollment among Jews soared. By 1964, 80% of Wisconsin’s young Jewish people attended a four-year college, usually in locations far away from their rural communities.

The pursuit of higher education was not the only factor that led to the Jewish vacuum in most of small-town Wisconsin. As shopping trends veered toward the large malls of the 1950s and beyond, many small family-owned Jewish businesses could not survive.

Those who grew up in Viroqua speak fondly of Felix’s General Store, where the townspeople could buy anything from boys’ undershirts to kitchen dish towels. Started in 1905 by Russian immigrant Max Felix, the store thrived for decades as Max’s son Rollie and later his grandson Steve joined him in business. Felix’s General Store later changed its name to Felix’s Men’s and Women’s Wear in the 1980s.

However, the more modern focus was not enough to keep the store in step with the wave of the future. In 2000, Felix’s closed its doors after it could no longer compete with the larger retail chains that had begun to appear in small-town malls.

In Sheboygan, Hoffman’s Flowerland survived as the last Jewish-owned shop in the city.

Despite the demise of many family-owned establishments, some Jewish businesses that began in rural communities grew to become successful statewide or even nationwide companies.

The 500-seat Campus Theatre, started by Ben Marcus in Ripon, grew into the Milwaukee-based Marcus Corporation, a major network of hotels, restaurants and theaters that dot the state.

Lewis E. Phillips set up shop in Eau Claire to sell his newly invented cookware device called a pressure cooker. His small business blossomed to become a major corporation known throughout the country as National Presto Industries, Inc. Eau Claire’s Memorial Public Library, the planetarium within the Science Hall of the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire, and the Eau Claire Senior Center bear the Phillips name in testimony to his philanthropic desire to give back to the city that provided him with so much opportunity.

Although many businesses successfully flourished beyond their small-town beginnings, by the late 1900s little remained of the Jewish communities in cities such as Stevens Point.

The white clapboard building that was Beth Israel Congregation is all that remains of the once-thriving Jewish community. In the 1980s, when the congregation no longer had enough members to form a minyan, the building was deeded to the Portage County Historical Society. Now it houses a museum that serves as a reminder of the once vital Jewish presence in the city.

By 1965, the Moses Montefiore membership in Appleton had voted to join the United Synagogues of America, which officially made it a part of the Jewish Conservative movement. This change made it possible for men and women to sit together during religious services and gave greater recognition to the important roles that women had always played in the health of the congregation as they held fund raising events and reached out to the greater community through charitable deeds.

As another sign of modernization, the yearly records that had been written in Yiddish were translated into English. On June 17, 1970, a new modern building on the city’s developing northeast side was proudly dedicated. Although its name remained the same, the distinct shift in its congregants’ needs over the years attracted new members and the promise of future growth.

However, the Jewish community of Appleton, once the second largest in the state, was not immune to the demographic shifts of the latter 1900s. Before long the membership of the new congregation began to slip away, necessitating a move to a smaller facility and the employment of a part-time rabbi for the small number of Jews who stayed.

In Sheboygan, once home to three Orthodox synagogues at the peak of Wisconsin’s Jewish diaspora, only Congregation Beth El has remained. The membership of the once crowded Conservative synagogue has become too small to retain a rabbi. Instead, two laypeople from the congregation started to conduct weekly services.

“We’re just trying to hang on,” resident Harold Holman said. In spite of that sense of loss, he is clear about his continuing fondness for the city. “I’m very proud of Sheboygan. I’ve had a good life here.”

Although he still enjoys living in his hometown, he regrets having watched the Jewish community shrink down to approximately thirty families. “It’s a sad story,” he said. “It all fell apart when the kids left and never came back.”

Holman is not alone in his affection for the city. More than three hundred Jewish former residents returned to Sheboygan for a reunion in August 1999. Holman, who was a co-chair of the event, recalled, “They flocked here from all over the United States, France and Israel.”

They were there to reminisce, to exchange tales about growing up together, and to pay homage to a place where they thrived, establishing successful businesses and becoming part of the secular community where they felt safe and welcomed.

Perhaps David Schoenkin, whose grandfather Charles settled in Sheboygan as a scrap iron peddler, best summed it up when he told the Sheboygan Press, “Wisconsin opened its arms to those who wanted to build new lives and have the freedom to practice their religion.”

Not every small-town Jewish congregation suffered closure due to 20th -century changes, however.

Congregation Sons of Abraham in La Crosse has kept its doors open to serve approximately 125 congregants. Although by 1948 its members had enough financial stability to build a formal Orthodox synagogue, it could not sustain itself by the later 1900s. By 1992 it morphed into a Conservative congregation under the guidance of Rabbi Simcha Prombaum. Slowly its membership numbers climbed as the congregation drew religious Jews from the surrounding areas of Viroqua, Tomah, and parts of southeastern Minnesota, where Jewish communities lacked enough people to have their own synagogues.

Following suit, Wausau’s Mt. Sinai Reform Temple meets the religious needs of Jews from that city and the surrounding towns of Stevens Point and Marshfield. And Green Bay’s Congregation Cnesses Israel remains an active force in that community.

On September 21, 1953, the Jewish community of Green Bay celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the congregation’s existence. At the ceremony, these words were spoken about the first few Jewish families in Green Bay:

The little group grew and flourished. Somehow they found their way to these two little northern communities of Green Bay and Fort Howard. John Baum came here from Boston, where he had fled from Russian Poland. William Sauber, a candy salesman, thirsted for intellectual companionship in the long lamp-lit evening and found it with Azriel Kanter and others who gathered at the Kanter home on Madison and Lake streets. Here then were the roots of a Jewish community. Above all else, they felt the need for prayer, for solace, for faith in their Creator to whom all Jews had turned throughout the ages. Soberly on each Friday afternoon they left their arduous tasks of the week, arrayed themselves in their very best, and prepared to welcome the Sabbath. Fortunately, in Azriel Kanter, they had a spiritual leader. He was teacher, shochet, chazen [cantor] and mohel [one who performs ceremonial circumcisions] combined and served the others in these various capacities. His home became the spiritual meeting place for the little group. . . . September 15, 1889, there was filed in the Office of Register of Deeds for Brown County formal Articles of Organization for Congregation Cnesses Israel of Green Bay, Wisconsin. The incorporators were listed as Isaac Cohen, William Sauber, and Rev. Azriel Kanter. . . . Sunday, September 4, 1904, just six days before Rosh Hashanah, was the great day — the opening of the shule of their own. William Sauber and B. Bronstein had the honor of carrying the two scrolls of Holy Writ from the basement. Each member in turn proudly ascended the altar steps and stood attentively while Azriel Kanter read a portion from the Torah.

Far from the ideas of its earliest founders, Congregation Cnesses has added a 21st-century twist to its Conservative form of Judaism — a woman rabbi, Rabbi Shaina Bacharach, joins ranks with Dena Feingold, who grew up in Janesville and became the first woman rabbi in the state in 1985. Rabbi Feingold went on to preside as the spiritual leader of the Beth Hillel Reform Temple in Kenosha.

Rabbi Feingold recalls her family’s efforts to maintain Jewish practices while she was growing up in Janesville as the only Jewish girl her age in the town.

“Being in a community where there are not many Jews forces you to consider your own religious identity,” Feingold said.

Her family made sure that as well as being very involved in the interfaith community, she and her siblings received exposure to their religious roots by traveling to the closest Jewish congregation for both Hebrew school and religious holiday services.

Although the Jewish life in small-town Wisconsin has become only a footnote in the Jewish history of the state, many people who grew up and flourished in such communities look back with the fondest of memories.

Barbara Garber Essock, who spent her childhood in Wisconsin Rapids, later recalled, “I had wonderful memories growing up in the Rapids and look back on my life as one of many more good times than bad — and always filled with love and security.”

The postwar boom in Milwaukee and Madison

A righteous man falls down seven times and gets up. —King Solomon, Proverbs 24:16

In contrast to the dwindling Jewish communities in small towns, Milwaukee and Madison maintained the largest Jewish populations in the state in the second half of the 20th century.

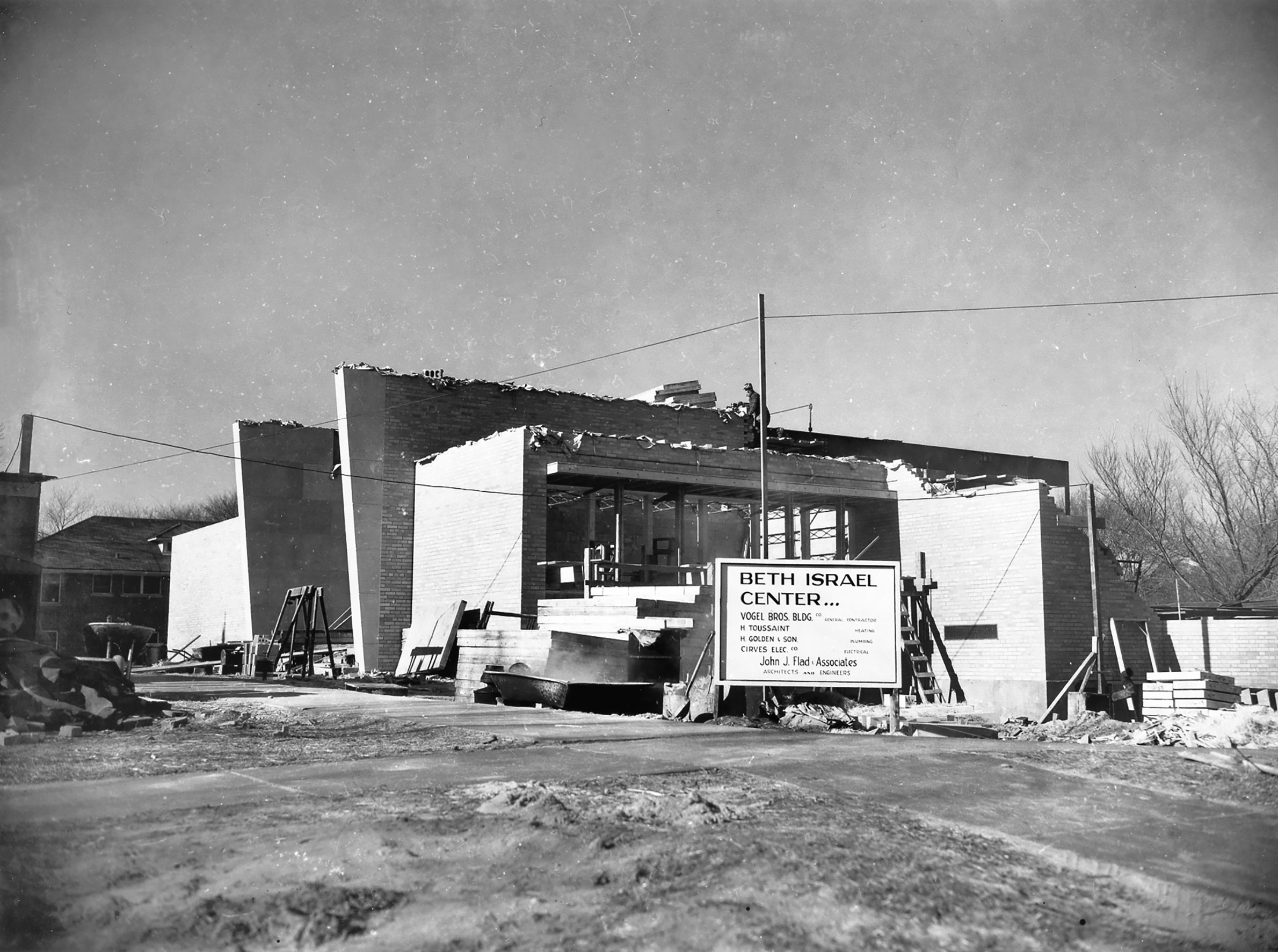

To accommodate the religious needs of the Madison community, two new religious buildings were erected to replace three smaller synagogues that included Beth Jacob, Adas Jeshurun and Agudas Achim. In 1950, the Agudas Achim congregation changed both its name and its building to become Beth Israel Center. Twelve years later, Adas Jeshrun closed its doors to join forces with the new congregation.

Although Beth Israel was considered less Orthodox than any of its predecessors, it did not officially join the Conservative movement until the late 1960s. As the first Conservative synagogue in Madison, it added yet another stratum of Jewish worship to the community. Congregants who sought out religious observance that fell somewhere in between the rigorous adherence to Orthodox traditional practices and the more modern approach of the Reform temples found their place there.

Temple Beth El, which was founded in 1939, dedicated its new building the same year with a Reform service that included the singing of “Ayn Kelahaynu” (No one like our Lord) and “America the Beautiful.” These song choices reflected the congregants’ devotion to the Jewish faith combined with a desire to assimilate to the new world in which they were living.

As an example of the interfaith fellowship that existed, Rev. Alfred W. Swan of Madison’s First Congregational Church expressed the growing respect for Wisconsin’s Jewish population when speaking at Temple Beth El’s dedication: “To the Synagogue the world is forever indebted for the origin and inspiration of the Word of God. . . . May the days of our years and yours find us together in unbroken fellowship as citizens in our fair and fortunate land.”

During the 1950s, the city of Milwaukee maintained varied congregations where Jews could express their religious faith in whatever way they chose, be it Orthodox, Conservative or Reform. However, Rabbi Louis Switchkow, who led the Conservative congregation Beth El Ner Tamid and coauthored the book A History of Jews in Milwaukee in 1963, opined that Orthodoxy in the postwar period was “a very tenuous affair.”

In later years, in fact, the choices broadened in both Madison and Milwaukee to include Hassidic, Orthodox, Conservative, Reconstructionist and Humanist groups.

By 1951, physicians, lawyers, and successful businessmen had replaced the Jewish peddlers of days gone by. Although Jews made up only 3% of Milwaukee’s population, 20% of the doctors and 17% of the attorneys in the city were Jewish.

Jews also provided significant contributions to other industries. The needlework trade of yesteryear was transformed into nationally known clothing lines such as Florence Eiseman children’s clothes and Jack Winter designs. Kohl’s corner grocery store in suburban Milwaukee’s Bay View became Wisconsin’s largest grocery store chain, and Aaron Scheinfeld and Elmer Winter founded Manpower, which provided millions of offices with temporary help. Harry Soref and Samuel Stahl developed a laminated padlock that has become internationally known as Master Lock, while Max H. Karl founded the Mortgage Guarantee Insurance Company (MGIC), the largest private mortgage insurer in the world.

As the Jewish community prospered, its members never forgot those less fortunate in their midst. The recent war had left plenty of reminders of those needing help in its wake. They were the soldiers who returned home with prosthetic hooks for hands and the shell-shocked who struggled with memories that could not easily be shaken.

To meet their needs, the Jewish community of Milwaukee called upon the Jewish Vocational Service, first established in 1938 to help people who had lost their jobs during the Great Depression. In the postwar period this organization ramped up to help the wounded retrain and adjust to life with new disabilities.

It was the first rehabilitation agency in the United States and by 1980 had become the largest in the nation outside of New York City. Its staff, which grew to include 600 people, served not only veterans of the war but also the elderly, war refugees and welfare recipients.

In addition, Milwaukee’s Jews who had been able to flee Germany before the war began had established the New Home Club to help themselves adjust to their lives in Milwaukee. The organization was infused with a fresh vitality as Jewish survivors of the Holocaust joined their predecessors. Like the many organizations that originated in the 1800s, the New Home Club offered civics and English classes to the latest group, who had lost so much and needed to start anew.

Many displaced persons were employed through their Jewish neighbors or relatives. Some, like immigrant generations who had come before them, eventually developed businesses on their own.

Harri Hoffmann, who escaped Kristallnacht, founded Hoffco Shoe Polish Company in the late 1940s, after selling the polish from door to door that his wife, Herta, concocted in their kitchen. The Harri Hoffmann Company remains in operation on Milwaukee’s North Water Street as a symbol of the vital manufacturing entrepreneurship of the past.

Alfred Bader, who at age 14 fled Austria via the Kindertransport in 1938, was interned in a Canadian camp with other European refugees suspected of being “alien enemies.” Such fenced-in encampments were scattered throughout the United States and Canada until after the war was over. Upon his release Bader studied chemical engineering at Queen’s University and Harvard. When he arrived in Milwaukee as a paint chemist, he cofounded the Aldrich Chemical Company in 1951. It eventually became the largest supplier of organic paint in the nation.

As the list goes on, perhaps Joseph Peltz best articulated the can-do attitude that prevailed at the time. Having gone from a junk dealer to owner of a very successful recycling business, Peltz said in a 1956 interview, “There is no country like America. . . . If you have the spirit, nothing can stop you.”

This item was excerpted from Jews in Wisconsin, published by Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

Sheila Terman Cohen is a journalist and author who has written three Badger Biographies for the Wisconsin Historical Society Press: Mai Ya’s Long Journey, Gaylord Nelson: Champion for Our Earth and Sterling North and the Story of Rascal. Her books have received recognition from the Council for Wisconsin Writers, the Midwest Independent Publishers Association, and the national book award group Next Generation. As a freelance writer, Cohen has also written articles that have been published in a variety of newspapers, including the Wisconsin State Journal, the Capital Times, La Comunidad and Isthmus. Before studying journalism at the University of Wisconsin, Cohen taught English as a Second Language in the Madison schools.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us