When Deer Hunting In Wisconsin Shifted From Slaughter To Sport

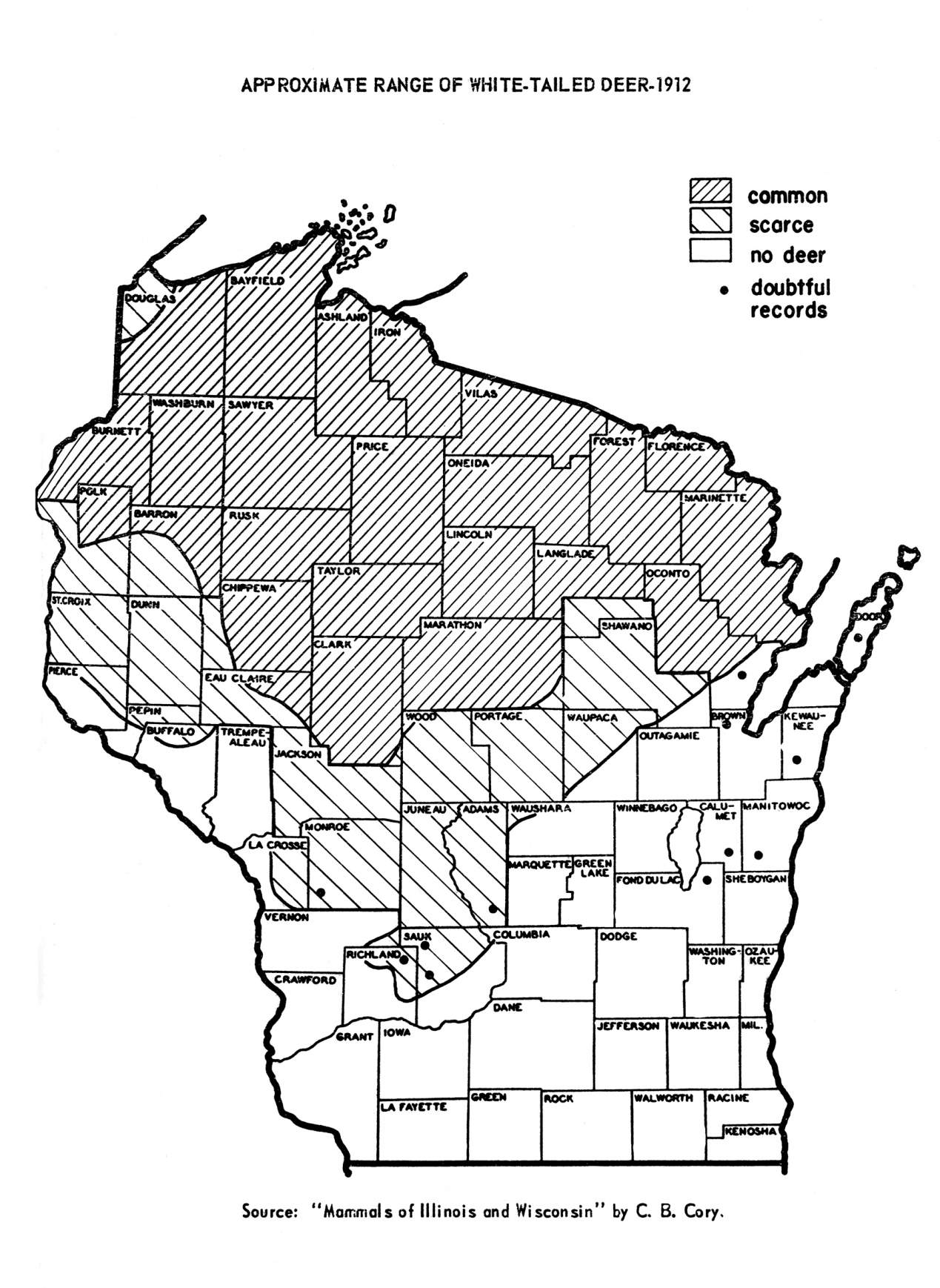

Hardly more than a century ago, deer were not to be found across broad swaths of southern and eastern parts of Wisconsin, with their dwindling ranks limited to its northern stretches after decades of mass hunts for hide and meat markets in the latter half of the 1800s.

November 27, 2019

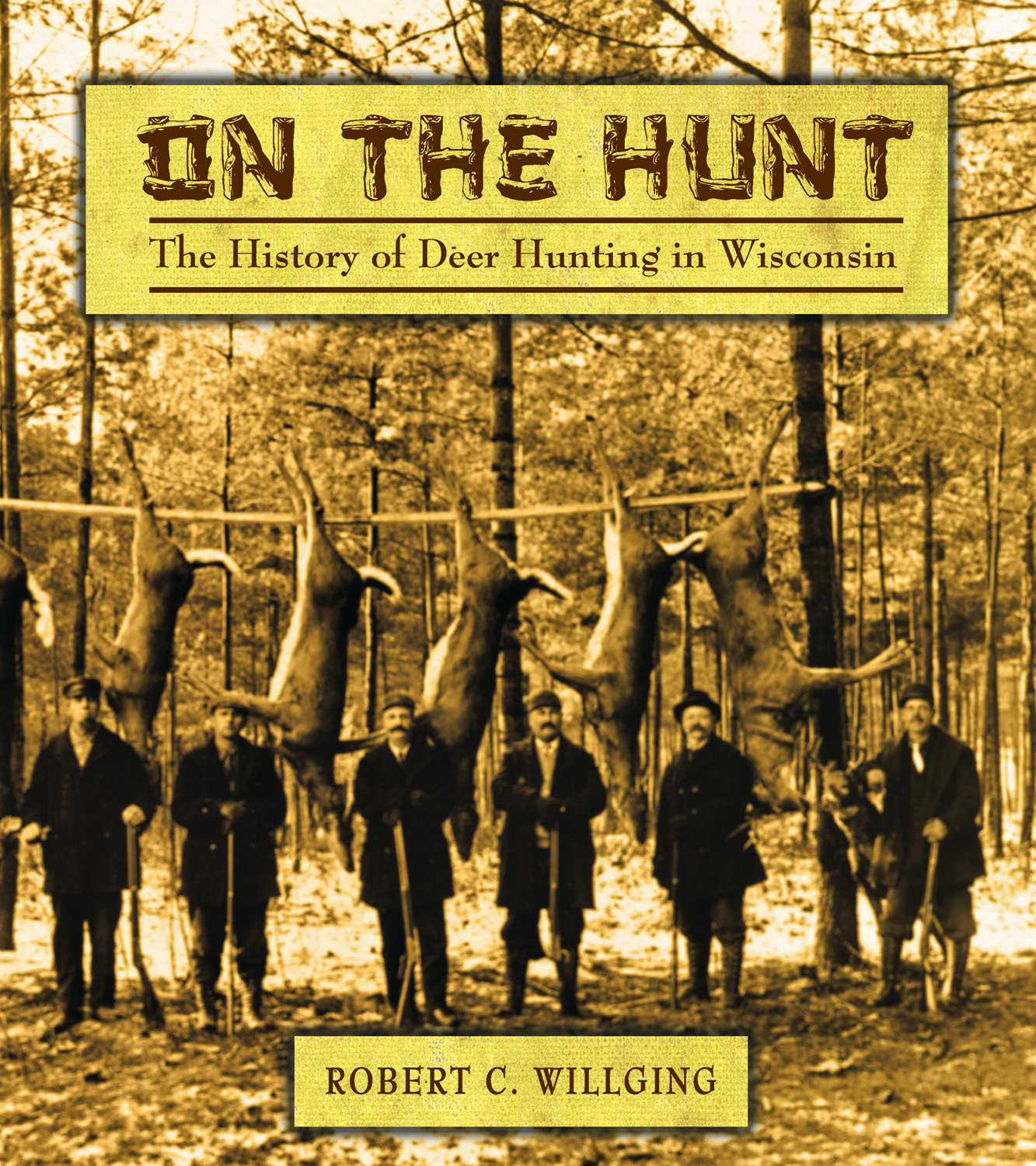

Three deer hunters near Donald in Taylor County in 1904

Deer hunting is foundational to Wisconsin’s identity as a state, with its pilgrimage to field and forest helping define the change of seasons and renewal of bonds with family and friends. The contours of this annual tradition developed over many decades, and depend on the relationship between humans, whitetails and the habitat that sustains them and other wildlife. Deer are ubiquitous across Wisconsin in the 21st century, with a herd that’s a million-and-a-half animals strong making for regular backyard sightings and all-too-common vehicle collisions. But hardly more than a century ago, deer were not to be found across broad swaths of southern and eastern parts of the state, with their dwindling ranks limited to its northern stretches after decades of mass hunts for hide and meat markets in the latter half of the 1800s. Over the first half of the 1900s, though, an ethic and subsequent science of wildlife management would emerge and develop as deer hunting transformed into a sport. Hunters and communities across Wisconsin would grow committed to fostering a sustainable herd as it recovered and started flourishing once again. While debates over how best to achieve this goal would simmer, erupt and settle again and again, continuing to this day, the customs of the autumnal deer hunt have become ingrained and venerated. In On the Hunt: The History of Deer Hunting in Wisconsin, published by Wisconsin Historical Society Press, author Robert C. Willging explores how an integral aspect of the state’s culture took shape. An excerpt from the book details how the idea of deer hunting as a sport and community tradition took root during the first decade of the 20th century.

The real hunter doesn’t slam car doors and clank off into the woods. He pays attention to breezes, he notices rubbings, he sees a variety of distances from food to resting areas and watering spots. He puts all this information together and uses it at the right time of day, quietly and with that special alertness, that sixth sense, and he sees deer. If he chooses to shoot or not, if he wants a trophy or roast venison, that is his final option, but he has derived his basic satisfaction from solving the problem. —Gene Hill, A Listening Walk

Americans were optimistic as the first decade of the new century began in 1900. The country was poised for great things. Railroads were spreading across the United States, cities were being electrified, and industry was expanding. America was growing at a fast pace, eager to take its place among world leaders.

William McKinley was reelected president in November 1900 on a Republican ticket with Theodore Roosevelt as his running mate. Fate carried by an assassin’s bullet made Roosevelt president in 1901; he dominated American politics for the remainder of the decade. An intense and spirited sportsman and adventurer, he was destined to be at the forefront of the era of American conservation that was on the rise.

Conservation of natural resources was not on the minds of most Wisconsin deer hunters in the early “ought” years. The state’s population was just more than two million people in 1900, most of whom lived in farming or rural areas. While deer populations had reached historic lows in states to the east, and hunters there faced increasingly restrictive or closed seasons, Wisconsinites had some reason to be optimistic about hunting prospects: Deer numbers were actually increasing in some areas. The trick was to go to where the deer were.

Market hunting, increased human settlement with a heavy reliance on deer for subsistence, and habitat changes had decimated deer populations in most Eastern and Midwestern states by this time. Southern Wisconsin was typical of the situation. By the turn of the century, deer were so rare in southern counties that the mere observation of a single deer was fodder for excited talk and speculation at the barbershops and taverns. Deer mainly existed in areas of heavy cover, such as along creeks and rivers.

This wasn’t the case in northern Wisconsin, however. During the first years of the 1900s, most northern counties reported deer to be plentiful and hunting to be good. A Rhinelander newspaper, The New North, reported deer during the season of 1901 to be numerous and stated that “already a large number have been brought to this city.” It was ironic that the whitetail had been literally shot out of southern counties, where the farm, field and forest habitats were more favorable to deer, while herd populations seemed to be increasing in the northern forest, which had typically been poor habitat because of its heavy forests and hard winters.

The favorable blip in deer populations in the north was mostly due to changing habitat conditions in the wake of large-scale Northwoods logging. The era of the great pineries was coming to a close, but logging was still big business in northern Wisconsin. In its aftermath, deer benefited from the brush and second-growth forests replacing the big trees.

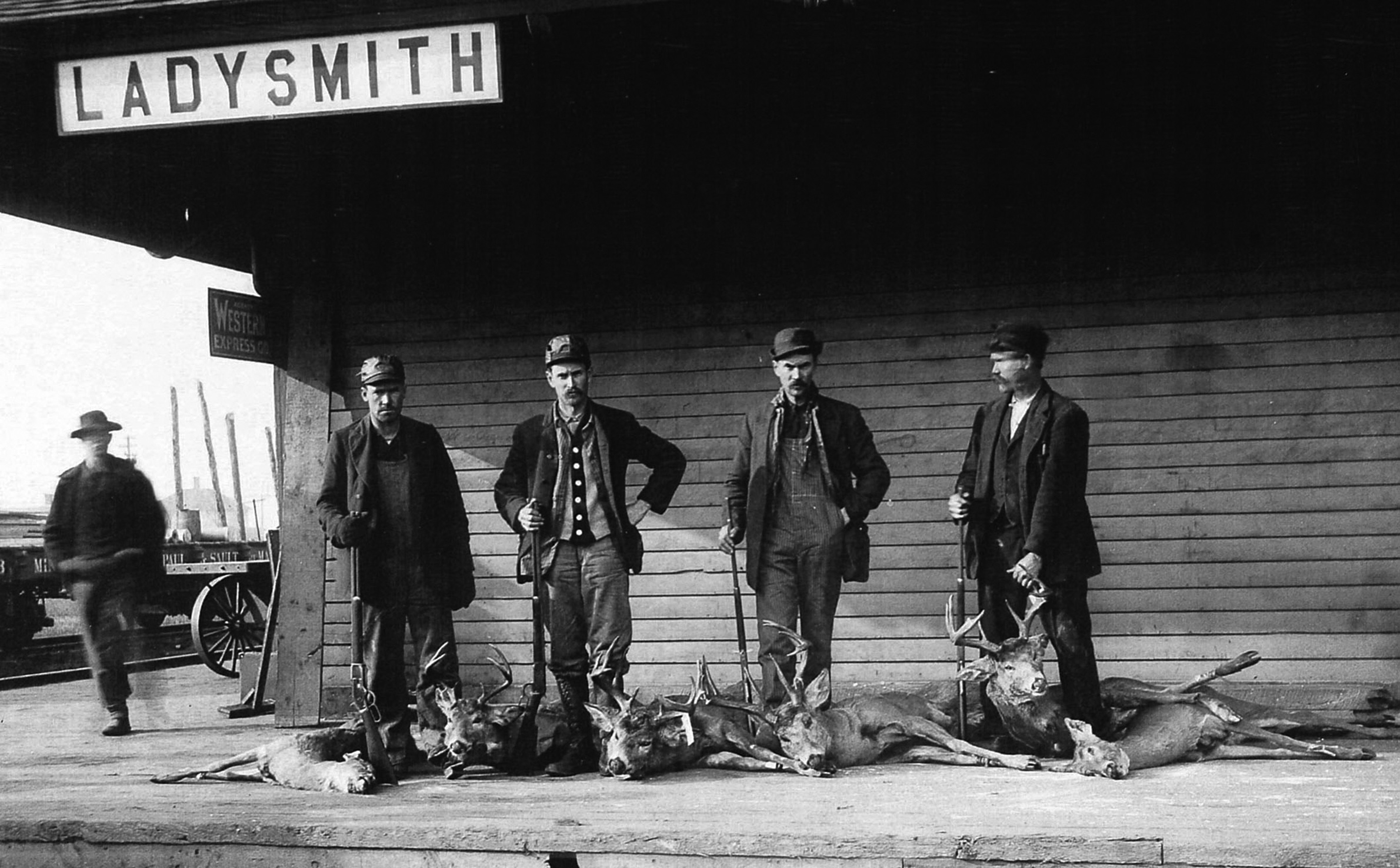

Because of the scarcity of deer elsewhere, northern Wisconsin began to see a new phenomenon: an increase in hunters from somewhere besides northern Wisconsin — primarily from southern counties but also from outside the state — who traveled north for the opportunity to hunt deer.

“The annual slaughter of deer began Monday morning and for several days prior to that time, hunters came pouring into the city from every direction,” reported The New North in 1901. In 1905 the newspaper noted that “hunters from the south are arriving on every train.”

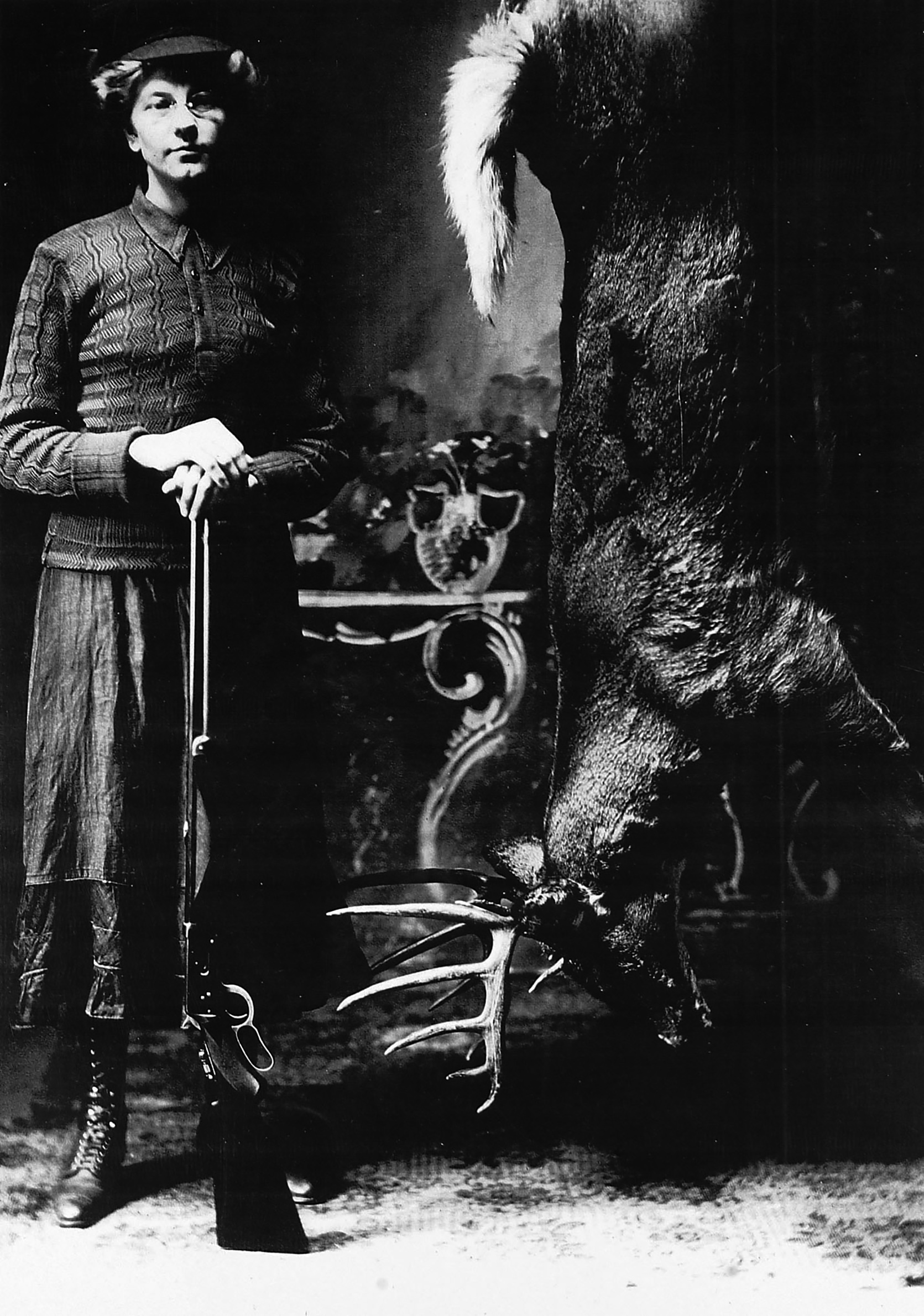

These hunters represented a new and growing segment of the American hunting population: the sportsman. Rather than hunting out of the necessity to feed a family or, as in the case of the market hunter, for profit, the sportsman placed primary value on the experience of the hunt. This new breed of hunter was willing to travel, sometimes great distances, simply for a fulfilling recreational hunting experience.

Getting to the northern counties to pursue the sport of deer hunting was not particularly difficult, and it was getting easier. Although automobiles were scarce (only about 8,000 existed in the entire U.S. in 1900) and roads on which to drive them few, railroads were booming. These “roads” provided hunters access to the very heart of the northern deer country. The state and the railroad corporations, anxious to sell land and increase settlement in the north, promoted the idea of using the rails to reach deer.

The 1904 “Official Railroad Map of Wisconsin” included text that stated, “The northern portion of Wisconsin may be justly called a sportsman’s paradise, both for fishing and hunting. Deer hunting along the lines of the Wisconsin Central is exceptionally good during the open season.”

The major railroads, as well as smaller, local lines, such as the Dunbar and Wausaukee in Marinette County, Hazelhurst and Southeastern in Oneida County, and Chippewa River and Northern in Gates (later renamed Rusk) County, passed through small settlements and logging camps with now-forgotten names like Bagdad, Sillhawn and Veazy.

It was a good situation for hunters, who typically set up camps in proximity to railroad access or used abandoned logging camps, of which there were many. Locals with horses and wagons were eager to provide transportation for hunters and gear.

The season framework itself was a pretty simple affair. In the “ought” years, the deer season ran for twenty days each year and, except for 1900, when the season started Nov. 1, the seasons began Nov. 11. Since 1897, hunters could take two deer of either sex. This continued until 1909 when a one deer, either sex bag became law.

A deer license cost a Wisconsin resident just one dollar; a nonresident paid $30. Licenses were generally bought from the county clerk at the local courthouse, and the county was allowed to keep 10% of the revenue from each license sold.

There was a requirement to tag deer with a paper tag prior to transport or shipping. After receiving numerous inquiries regarding the proper shipment of deer, The New North printed the law: “No deer or part of a carcass can be shipped, but must be accompanied by the hunter, with coupon section ‘B’ of his license attached to it. If a non-resident, sections B and C are to be attached to the carcass or part of the deer.”

This rule was not strictly followed; when it was, many a hunter returned from the woods to find his tag was no longer attached to his deer.

Hunters had complained about the paper tags for years. A hunter from Milwaukee, Judge Neele B. Neelen, had taken two deer in Vilas County in 1901. The New North printed some of his comments regarding the season:

There is one amendment to the present game law that ought to be adopted. It relates to the tags which, according to law, must be attached to the deer before they can be shipped. The paper tag, now used, is not sufficient, because it is lost too easily. It is simply a frail piece of paper and easily blown away.

The deer are sometimes carted twenty or thirty miles before they get to a railway station where they may be shipped. I know a prominent business man in this city who was obliged to give away a deer he had shot because the tag was lost between the camp and the railway station. I always wrapped my tag up in a piece of cloth and tied it tightly to the deer’s horn, so that it could not get lost. I should suggest that a tin tag might be used and attached around the deer’s neck with wire.

It wasn’t until 1920 that the problem was solved. The new tag, which consisted of a strip of tin with a ball at one end, was sturdier than its predecessor. After the strip was slid through a deer’s gambrel, one end was pushed into the ball, locking it permanently.

“The new tags must be a source of interest to those hunters who received them,” stated Wisconsin Conservation Commissioner W. E. Barber, “for many have written for new ones because they inadvertently locked theirs while experimenting with them.”

The new metal tags were destined to tempt hunters to lock them prematurely for decades to come.

In the early years of the decade, deer hunting regulations were minimal and enforcement of those laws limited due to the scarcity of game wardens. When wardens were present, their performance in pursuit of violators frequently was lackluster. The New North sarcastically reported on the actions of the local wardens in 1902:

At Last! At Last! Our State Game Wardens Have Captured Someone Who Has Been Violating the Law.

The first crop of hunters of the season of 1902 was rounded up in Paul Browne’s Municipal Court rooms last week. They are all good citizens who probably went hunting just this once during the year. They were in [the] charge of Deputy Game Wardens E. A. VanAerman and Martin Berg, who caught them in the act of hunting deer with dogs. They were promptly convicted, in fact plead guilty, and were fined $25.00 and costs which they paid. This is the first arrest that has been made in this county during the deer hunting season for any violation of the game laws and at least 260 deer have been killed in this county the present season. It is a fine illustration of the ridiculous inefficiency of our present system of protecting game, and brings to view the tireless, tenacious, sleuth-like following which game wardens have given the hunters in this vicinity! There have been at least twenty parties of hunters in Oneida county out for deer with dogs during the season, and a good many were out before the season opened. Not an arrest has been made. Not a complaint, nor a whimper has been heard from any of the game wardens. Deer have been slaughtered plentifully and unlawfully throughout the northern woods this year. The law regarding the time, dogs and headlights has been disobeyed with an openness and wantonness that has never been equalled. Madison official dispatches as to the game wardens effectiveness are simply laughable. Talk indulged by game wardens and the showings made by the papers which seek to praise the system and defend its efficiency are ridiculous in the face of the facts. People up here know what these facts are, if they are posted. We believe that fewer deer would be illegally hunted and killed, if the duty of enforcing laws regarding game was in the hands of the daily constituted officers of towns and counties and the game wardens’ positions were all abolished. Let a heavier penalty be inflicted in case of conviction of violation of these laws and let the officers of a town and county attend to their enforcement. The game warden business is a farce so far as this section of the state is concerned. It is no joke with the taxpayers however, but the ineffectiveness of the system has been so well disproven that some sort of change should be made.

Whether the criticism of the local wardens was wholly warranted or the result of local politics, it was true that the early wardens were not always successful in their attempts to enforce game laws. They were few and far between in a part of the state still vast and remote. The accusations against a “system” that let game-law violators off with a slap on the wrist — if even that — symbolized the growing feelings of many residents of small Northwoods towns that the state was not doing enough to pass and enforce regulations to control deer hunting.

The running of deer with dogs was still a common practice in some areas in the early 1900s, though not allowed by law or acceptable by general public opinion. Accepted methods to bag a deer varied by locale, but in many locations it was still anything goes. Most often, deer were taken by recreational hunters sitting on stumps near runways or paths of travel, by still-hunting (the practice of slowly stalking a deer), or during deer drives.

Hunting over a salt lick from a high point or scaffold was common in areas with lower deer populations. The use of salt licks was banned in 1909, but it would be many years before the practice disappeared. Set guns, the old market hunter’s tool, were banned in 1869 but continued to be used into the early 1900s. A deer hunter was killed by a set gun during the 1905 season.

The firearms being used in the Northwoods were a unique mix of old and new technology. Great strides in rifle development had been made since the Civil War, spurred on by demands from both the military for accurate, dependable weapons for use on the western frontier and the growing ranks of sportsmen looking for the perfect game rifle.

A Wisconsin deer camp might have in its armory a wide variety of firearms chambered for an equally wide variety of cartridges. Civil War-era weapons, or “sporterized” versions of them, were readily available and popular with hunters after the war.

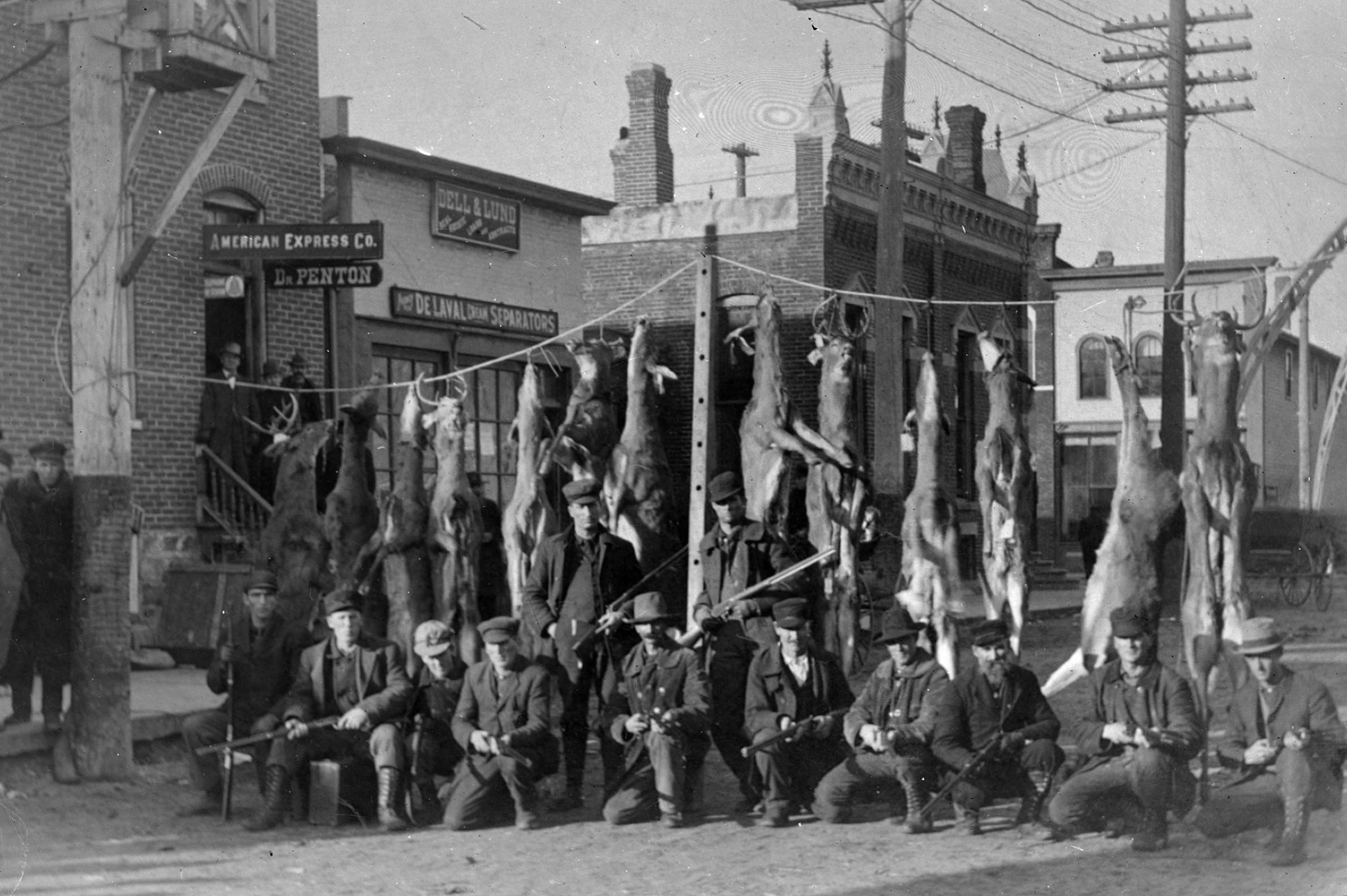

Whatever the method or firearm used, it became clear by the deer seasons of 1905 and 1906 that more and more hunters were killing more and more deer in northern Wisconsin. A newspaper report from Woodruff warned, “The slaughter of deer is likely to be greater this year than it has been for some time. If this continues for a few years more, those swift footed animals of our American forests will soon be as rare a sight as the buffalo.”

In the early 1900s it was difficult to know just how many deer were being killed during each deer season. Most estimates of the kill were based on the numbers of deer shipped south on the railroads. In 1907 the state’s chief warden reported that about 5,600 deer had been transported by the railroads. But he estimated the kill at 10,000, allowing for deer taken straight home or those consumed at camp.

Another gauge of hunting pressure was the number of licenses sold.

A 1908 newspaper report gave a conservative estimate of 75,000 hunters in northern Wisconsin — an unprecedented number for the time. After the 1908 season, the state’s chief warden, again using the number of deer transported (6,268) as a base, estimated the deer take at 11,000 — a 1,000-deer increase from the previous year.

In response, The New North noted, “At this rate it can be plainly seen that unless steps are adopted for more rigid game laws that in time there will be few deer left to kill.”

Residents of the small logging towns like Rhinelander, Mercer and Hayward were witness to the thousands of sport hunters pouring into the north, as well as to the thousands of deer heading south by rail.

“Up to the present time few deer have been brought to the city although the express car of every train thru here for the last few days has been loaded with carcasses,” reported one Northwoods newspaper.

However, as had already occurred in Eastern states, by the end of the decade, Wisconsin deer hunting philosophy was gradually shifting from an “anything goes” attitude to a “save the deer” attitude. Sportsmen realized that changes must be made if the sport of deer hunting was to survive.

Sportsmen’s clubs were formed across the state, with very similar agendas. In January 1909, forty sportsmen, including the local game warden, assembled at Rhinelander City Hall to establish the Rhinelander Hunting and Fishing Club. The club immediately addressed deer season regulations, drafting a resolution to forward to the state legislature urging adoption of a law to license all nonresident hunters and to limit hunters “to only one deer per license issued each season.” They also recommended a closed season for all game during the first ten days of November, possibly with the intent to reduce illegal preseason hunting.

Perhaps the most significant recommendation from this hunting club was one echoed by others across the north: the idea that the one-deer bag limit should be for bucks only.

“W. B. LaSelle, one of the most enthusiastic nimrods in the county, has made it a rule for several seasons to kill only bucks,” reported a Rhinelander newspaper. “Mr. LaSelle opines that if sportsmen adhered strictly to this rule it would tend to prevent the extermination of deer.”

The reduced bag limit from two to one deer did occur for the 1909 season, but it was still an either sex rule. However, the growing fear that deer would become a memory akin to buffalo was very real at the time. In the next decade, Wisconsin deer hunters would begin to see a steady movement toward “buck only” laws, closed seasons and deer refuges. The deer protection movement was beginning.

This item was excerpted from On the Hunt: The History of Deer Hunting in Wisconsin, published by Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

Author Robert C. Willging is a freelance outdoor writer and is author of History Afield: Stories from the Golden Age of Wisconsin Sporting Life. His work has appeared in Deer & Deer Hunting, The Boundary Waters Journal, Wisconsin Outdoor Journal, Wisconsin Natural Resources, High Country News, Turkey Call, WildBird, The Trapper & Predator Caller, Fur-Fish-Game and other publications. He is a frequent contributor to Wisconsin Outdoor News. Willging holds a bachelor’s degree in wildlife management from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point and a master’s degree in wildlife sciences from New Mexico State University; he’s worked as a wildlife biologist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture since 1987.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us