Q&A: Andy Soth, Portraits From Rural Wisconsin

March 25, 2019 Leave a Comment

Portraits From Rural Wisconsin premieres 8 p.m. Thursday, April 11 on Wisconsin Public Television. Through a series of interwoven personal essays, see why some western Wisconsin residents still say that “rural life is the best life” – even in the face of hardship and change.

Producer/reporter Andy Soth, whose work has appeared on Here & Now, WisContext and Wisconsin Life (among others), spoke to us about the multi-year process that has brought these unique visual essays to life.

Producer/reporter Andy Soth, whose work has appeared on Here & Now, WisContext and Wisconsin Life (among others), spoke to us about the multi-year process that has brought these unique visual essays to life.

Why did you focus on western Wisconsin?

After the 2016 election, I saw the big swing in many counties that had supported Obama to supporting Trump as an indicator people felt things were not working. There was an openness to trying radically different approaches. It led me to do some reflection on how we could better cover these parts of the state.

My starting point was to look at those counties and areas that switched. I saw a group of them in western Wisconsin along the Mississippi River. I wasn’t interested in looking at purely partisan areas; I wanted to look at areas in which it seemed like voting behavior expressed dissatisfaction, then try to drill down and see what some of those issues might be.

I also felt it was important to have a sense of place. Jumping from northern Wisconsin to central and western Wisconsin, you’d lose that.

As viewers will see, though, the final product contains almost no politics, right?

I wasn’t really interested in doing a political story, or something that would predict the outcome of the next election, but rather looking at issues that were not being addressed that could make life more satisfying in the state’s rural areas – which have always been a vital part of Wisconsin.

The challenge was how much politics to engage. Immediately, it became divisive. I knew I could spend all my time trying to elicit a political conversation, or I could talk about everything else. I decided to take the latter strategy.

What drove you to seek outside funding and make it such a major project?

This is the first time I’ve done a full hour-long documentary.

I had just been talking to my colleagues about these topics when I heard about the O’Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism at Marquette University’s Diederich College of Communication. It’s affiliated with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel; one fellow is always a Journal Sentinel reporter. That part of the connection is part of what makes it such a valuable experience, because you get to meet other journalists and learn about some of the in-depth projects the Journal Sentinel does.

All the projects funded are in the public service; often they’re deep investigations. One of my colleagues was looking at servicing mental health in jails; another, Erin Richards of the Journal Sentinel, was looking at school mobility – students who move frequently from school to school, even during a single year, and the difficulty it makes for graduation rates and education.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: Meet the 2017-18 O’Brien Fellows here.]

The agreement is that they will fund a reporter’s time to go in-depth on a project, provided that they have an outlet for it – TV or newspaper. I was actually the first in television to be part of the fellowship.

In exchange for that opportunity, journalists are expected to bring Marquette students in, give them tangible work experience and things they can put into their portfolio for seeking employment after graduation.

I worked with a team of four students throughout the year, with varied interests: some photography, some in television journalism, reporting, some in policy research. One of them, Amelia Jones, is now an on-air reporter for the NBC affiliate here in Madison.

The time and space that the fellowship allowed me made it possible to give these stories room to grow. The O’Brien Fellowship really was the opportunity of a lifetime.

How did the project evolve?

I’d always wanted these issues to be a reporting focus, regardless of doing a large project or not, so even before the fellowship began, I did some reporting for Here & Now: transportation funding, difficulties in recruiting emergency services (EMTs) in small communities, rural broadband access.

These were all incorporated into WisContext coverage as well, going a little more in depth.

That started in January 2017. The actual fellowship started on campus as a residency in August 2017. Although I didn’t include broadband and transportation in this program, much of what I gathered for the EMT story is incorporated in.

During the fellowship, I did a story that aired on Here & Now about Tammy Olson, a feed mill owner who organized a public meeting as a reaction to the concerns of her clients. That also became a big part of Portraits. So even while I was working on the fellowship, I produced some content for Here & Now.

My biggest challenge was finding and shaping the stories. I thought, “Is this going to hold together?” I had a methodology, rather than a story. I thought I’d do four counties in four seasons, but things changed.

Having that throughline was one of the challenges of this documentary. They’re all such different stories.

How did you find some of the people involved?

In any small community, you find a lot of interconnections. I did take advantage of really strong local media.

As I researched local media, I came across Martha Gingras, a DJ on the country station WRDN-AM who had gone to UW-Superior. I knew that as a broadcast journalism student, she had to have been a student of [the late Wisconsin Public Radio reporter] Mike Simonson. Being able to drop that name was an immediate entrée to her being able to trust me and know what public broadcasting is about.

Much of the Pepin County stories came through my contact with her. She and her boss Brian Winnekins, the station owner, don’t tell so much of their personal stories, but give great background on the challenges the Durand community is facing, particularly when it comes to low milk prices.

I was very impressed by their operation. He’s a super solid ag journalist, in addition to being the owner of the radio station. They really serve their audience well.

Later, I moved south to Crawford County, where Charley Preusser, a newspaper editor from the Crawford County Independent/Kickapoo Scout, helped me. It’s a paper I would check into from time to time to search for stories for Wisconsin Life; a reporter, Emily Schendel, introduced us.

I looked more for stories, not just talking about issues. You’re trying to get to the people who are being affected, not approaching issues from a 10,000-foot view. In one case, I went to that public meeting and found a very outspoken person, John Nolan, then followed up with him in the parking lot and ended up telling a lot of his family’s story.

It was about knowing stories we wanted to tell and asking around, making those initial contacts. But there were a lot of stories that surprised me along the way, stories I didn’t expect.

As an example: I’d learned from talking to people that the Gays Mills food bank is an important resource for that part of the county.

There are restrictions on filming people who are receiving resources at a food bank. So we went to downtown Gays Mills, where the local motorcycle club was holding a fundraiser with a rock band. I thought that would be a more visually interesting way of introducing the food bank than just cans on a shelf. There, I met Steve George, the treasurer of the motorcycle club.

Later, I was interested in a story about rural economic development. In Soldiers Grove, a startup microbrewery is applying for grants and trying to get larger; I wanted to see if there would be a story there. In walks Steve; he’s also the Soldiers Grove village president, and deeply interested in helping the brewery get funding.

I drifted into that story by showing up to see what was going on, and ended up connecting with this person who has his feet in both of these different worlds.

As someone who doesn’t experience these issues every day, what sticks out to you?

There’s a tremendous value put on neighbors helping neighbors, and having a sense of community spirit. You run into that again and again. The challenges you’ll see are what’s making that harder and harder. If you look, for example, at the EMTs, changes in the economy – people having to go longer on a commute or having multiple jobs – make it that much harder to maintain a volunteer-driven system. Whether it’s EMTs or a food bank or neighbors helping each other make hay or help out in an emergency, that’s becoming increasingly challenging.

The changes in life are making a system that worked, but was always based on goodwill and volunteerism, more and more difficult. A small farmer may not have a neighbor anymore because his neighbor may have ended his operation. There’s that increased isolation.

As a field producer, how did you let people’s stories breathe, rather than structure them?

Viewers, I hope, will get a slice of life that gives a better sense of what it’s like to live in a rural area or small town for people who don’t live there. To me, the approach is about showing up with your sincere interest.

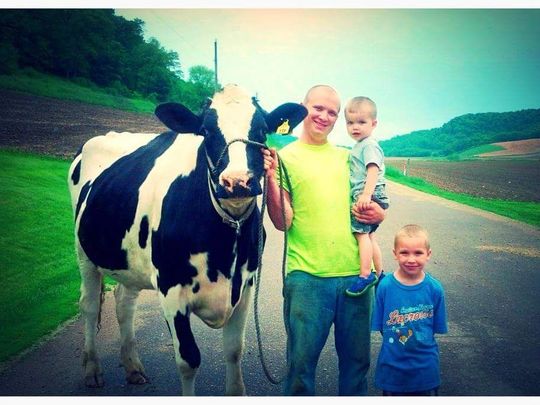

Weston Patnode and his young sons pose with one of their dairy cows before ending milk operations in 2017. (Photo: Jenni Patnode)

Surprisingly often, people share generously. Sitting on the Patnode family’s deck, I was caught off guard and moved by the immediacy of the emotions they shared recounting hard decisions they’ve faced about their small dairy farm’s future.

[Read “The last milking on Patnode Lane” by Jenni Patnode in the Wisconsin State Farmer]

The program isn’t heavily structured; it flows from place to place. It reflects the process of discovery I had: one person’s story leading me to another person’s story. I hope viewers get a sense of that.

News and Public Affairs Agriculture Farming PBS Wisconsin Documentaries featured Wisconsin Public Television Wisconsin Public Television

Passport

Passport