Preserving Lorine Niedecker's legacy in Fort Atkinson

How the Friends of Lorine Niedecker perform the careful, local work sharing the story of one of the 20th century’s most notable modernist poets

Preserving local history, especially in smaller cities and rural communities, is quiet, determined work. It’s typically carried out by a small organization or handful of devoted individuals who give their time and energy to care for the past. They stay curious about their community and how it changes over time: about the who and what of before and the ways these shape the present — about the quotidian and remarkable contours of place.

Ann Engelman, President of the Board of the Friends of Lorine Niedecker, stands beside a portrait of Lorine. (Source: Ann Engelman)

The 20th century poet Lorine Niedecker lived and wrote in near obscurity from her cabin on Blackhawk Island near Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin. During her lifetime, her work was not widely recognized, and it wasn’t until after her death in 1970 that she began to be acknowledged as a poet of consequence.

The work of introducing Niedecker to the community where she spent most of her life — sharing her work and inviting researchers to study her impact — has been carried out by two essential Fort Atkinson institutions: the Friends of Lorine Niedecker and the Hoard Historical Museum.

The story woven through Welcome Poets about the life of Niedecker, collaged with archival imagery, manuscripts and papers, could not have been told without their generosity.

PBS Wisconsin sat down with Ann Engelman, president of the Friends of Lorine Niedecker board, to learn more about their work and how they co-steward a literary legacy rooted in a small community far from the epicenters of the literary world.

Q: Lorine Niedecker is often referred to as a “little known” poet until just before her death — especially in Fort Atkinson, where she lived most of her life. The local work of the Friends of Lorine Niedecker (“the Friends”) and the Hoard Historical Museum has been essential to changing that. How did awareness of her begin to grow in Fort Atkinson?

Ann Engelman: When Lorine died in 1970, she had kept her life as a poet very private, except with the people she corresponded with in the larger poetry world. That world was really geographically and culturally outside of Fort Atkinson.

Cover of a local biography of Lorine Niedecker written by Jane Knox Shaw, p.1987. (Source: Friends of Lorine Niedecker)

About 10 years later, the local Tuesday Club — a women’s study group more than 150 years old — learned that a nationally recognized poet had lived in our community. This discovery inspired a woman in Fort Atkinson named Jane Knox Shaw to write a biography of Niedecker, based on research and interviews with people who had known Lorine. A few other publications appeared around the same time, but in the 1970s and 80s, poetry tended to be viewed as belonging to small literary circles, and wasn’t widely embraced in places like Fort Atkinson. The audience for Knox’s writing was very small.

Q: How did those early efforts evolve into the Friends of Lorine Niedecker?

A: In 2003, Woodland Pattern Book Center in Milwaukee, along with a burgeoning Friends group and the Dwight Foster Public Library, organized a centenary celebration of Lorine’s birth. That event drew people from around the world, including her literary executor from Japan, and sparked even more interest.

One of the participants, Amy Lutzke, assistant director of the library, began talking about the need for a permanent local organization dedicated to Lorine’s legacy. She invited me to join her, and together we’ve worked for the past 20 years to build the Friends of Lorine Niedecker. I say that humbly, while honoring that we built upon the hard work of earlier champions, like Mary Gates, then director of the Dwight Foster Public Library, and Marilla Fuge, an extraordinary library volunteer. When they retired, Amy and I stepped in to carry the work forward.

Q: After formally establishing the Friends, what were some of the first steps you took to share her work more widely?

A: Amy secured our 501(c)(3) status and arranged the first digital scans of Lorine’s work through UW–Madison’s Special Collections. From there, we set a goal to increase the visibility of her life and poetry at the local level. For 10 years we hosted annual poetry festivals.

It was also important for us to move poetry beyond the library and archives. One way we did that was by creating the first public poetry wall with Lorine’s words painted into a mural on the side of a local bar on Fort Atkinson’s main street.

The poetry wall became especially significant in 2008 when Fort Atkinson experienced the worst flood in its history, and the poem on the wall is Lorine’s line, “Fish / fowl / flood / Water lily mud / My life.” It felt as if the universe had aligned. That energy carried forward — in 2013 our local business, Scotties Eat-Mor, put up a sign that read “Welcome Poets,” at our request. This is the sign Nicholas Gulig talks about in PBS Wisconsin’s series and the inspiration for its title — it feels like all of these threads continue to come together in meaningful ways.

We also worked with the Fort Atkinson public school system to develop curricular materials on Niedecker for both middle and high school.

Q: Where are Lorine Niedecker’s local archival collections housed today?

A: For years her materials were split between the Dwight Foster Public Library and the Hoard Historical Museum. Al Millen, Lorine’s husband, donated her personal library of books to the library, while other papers and items went to the museum. Recently the collections were brought together, and everything is now housed at the Hoard Historical Museum. The museum lends important legitimacy to the archive and they have the preservation expertise and resources to maintain it. We’re very grateful to them.

The collection includes Lorine’s surviving papers, letters, and the small handmade books she created for her stepchildren, along with the Friends of Lorine Niedecker papers. These documents trace our research and, importantly, establish archival provenance. Because all the materials were originally organized by donor, it can be confusing to locate specific items. Our next step is to work with the museum to integrate the collections so researchers can more easily find what they need.

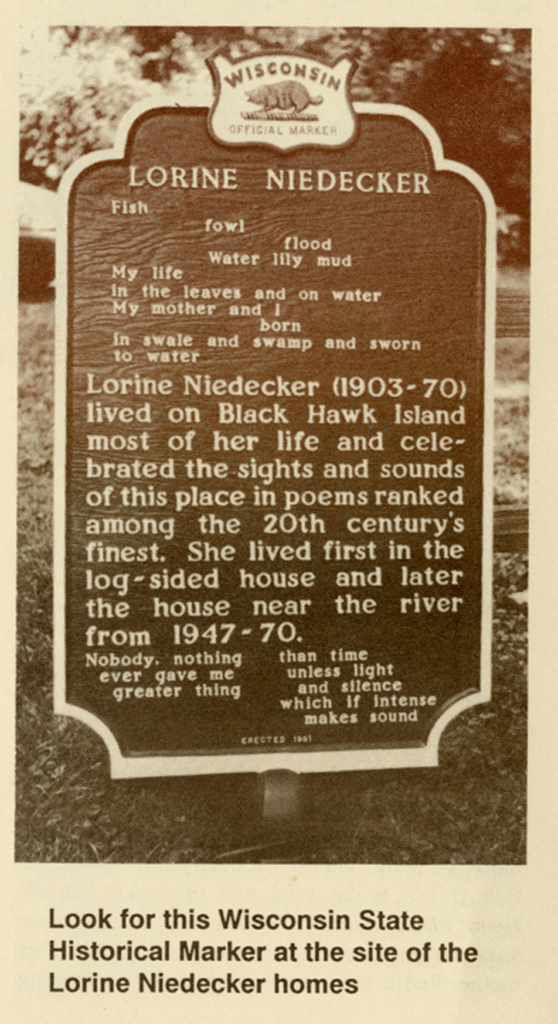

Q: What role did establishing Niedecker’s Wisconsin State Historical Marker play in raising awareness of her importance?

A: When the community applied for Niedecker’s state historical marker, the Wisconsin Historical Society initially rejected it, saying no one knew who she was.

A photo of the Lorine Niedecker Wisconsin State Historical Marker from a public brochure (Source: Dwight Foster Public Library, Fort Atkinson)

Supporters sent letters from around the world, and the marker was eventually approved in the early 1990’s. That moment gave real momentum to the community’s efforts to educate the state about Niedecker.

Q: How else have the Friends worked to preserve Niedecker’s legacy?

A: One of our early commitments was caring for her property, and the cabin from which she wrote on Blackhawk Island. It’s privately owned, but in exchange for help in maintaining it, we’ve been allowed to bring poets and others there for visits and events. The Wisconsin Historical Society also supported an application to put the cabin on the National Register of Historic Places. Today Lorine’s home is listed on both the state and national registries. Together, these efforts — archives, markers, preservation — created a foundation for sharing more stories about Niedecker’s life and work.

Q: What is the focus of the Friends work today?

A: In the early years, our priority was simply getting people in Fort Atkinson to know who she was. That took more than a decade. Now the focus is broader. Because of Welcome Poets, we can reach the whole state — and perhaps even audiences around the world. The digital series — because it was made by public media, and therefore any individual or organization can stream it without a paywall — makes Lorine’s story accessible in a way that wasn’t possible before.

Going forward, our priorities are twofold: First, to use Welcome Poets as fully as we can — through screenings, partnerships and robust promotion. Second, to continue the painstaking archival work that ensures Niedecker’s materials are properly preserved and accessible for the long term.

Q: Can you say more about the archival work?

A: Archiving is slow. Every item has to be accessioned, placed properly, and tracked for provenance — all the “iceberg” of work hidden beneath what a researcher eventually sees in an archival box or exhibit. I go into the Hoard Historical Museum every Tuesday to work on this. While working on Welcome Poets, PBS Wisconsin’s production researcher, Clara Philbrick, helped us start a database that is moving us forward, and the museum itself is moving further into the digital world. Collaboration is essential, since the museum is ultimately the keeper of the collection, even as the Friends contribute research and context.

Q: Beyond promoting the series and the archives, what other projects are priorities for the Friends today?

Cover of a pamphlet book of Niedecker’s poems collaboratively funded in Fort Atkinson and distributed for free to the community. (Source: Friends of Lorine Niedecker)

A: We sponsor the Lorine Niedecker Fellowship in partnership with Write On, Door County. We publish The Solitary Plover newsletter twice a year and now host virtual readings with Woodland Pattern Book Center in Milwaukee. We also present the Lorine Niedecker Lecture, which brings respected voices to speak about poetry in accessible ways. For me, accessibility is key. If I don’t understand a lecture — and I’m not a poet — then the audience has been missed. At the same time, we support the scholarly community through the Niedecker monograph series, What Region?, which publishes work for academic audiences.

Q: How do partnerships fit into this work?

A: Partnerships are everything. My view is that whomever has the most partnerships wins. That’s how we build visibility and impact. We’ve worked with organizations like Woodland Pattern, Write On, Door County, and the Madison Art & Lit Lab, which will be hosting a Welcome Poets screening. Each partnership expands Lorine’s reach and connects her poetry with new audiences!

Q: What are your feelings anticipating watching the series for the first time?

A: I know watching all six parts will be overwhelming. Lorine’s life and work are so close to my heart, and so important for Fort Atkinson’s history and the world of letters, that seeing them come alive on screen will be powerful. I also know the producer, writer and editor made really deliberate, thoughtful creative decisions while making it, which makes me even more curious and excited. When I do watch, I expect it will level me — in a beautiful way — with its force of emotion.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us