Diverse Voices

Veterans

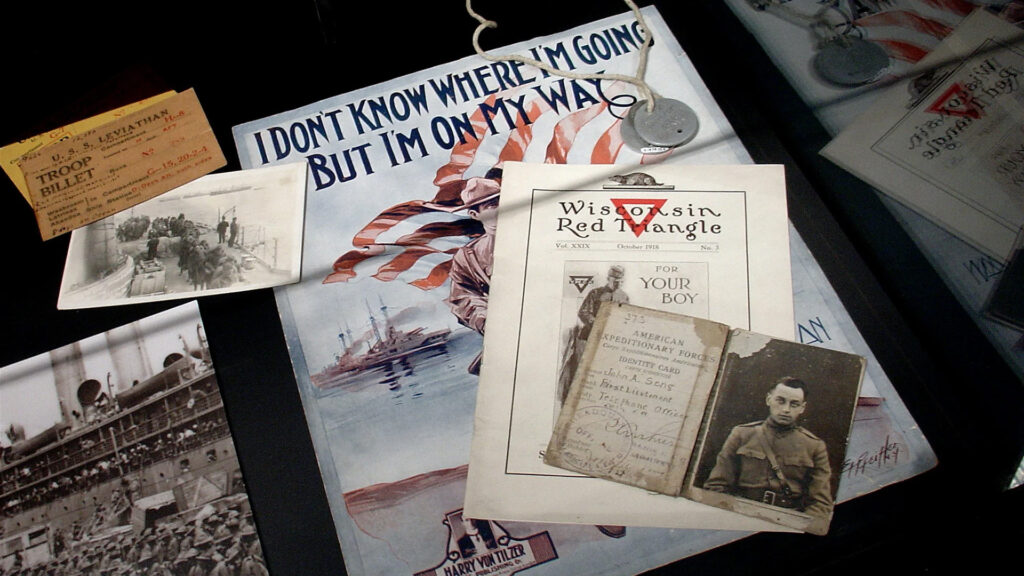

Delve into stories that honor the service, sacrifice and personal journeys of veterans from Wisconsin and across the nation. Learn about the toll of war, the path to homecoming, and the continued support veterans rely on and deserve.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us