Shipwrecks!

– Female Announcer: This program is brought to you by the combined resources of the Wisconsin Historical Society and PBS Wisconsin.

[resonating piano melody]

– Narrator: On the bottom of Wisconsin waters lie the wrecks of over 700 ships.

[bubbling]

Frozen in time, each tangle of wreckage sheds light on a maritime mystery: What ship is it? How was it built? What was it carrying? And what happened to the ship and the crew? Each shipwreck also tells a Wisconsin story of a state that grew strong because of shipping and the Great Lakes,

[bird cawing]

of Wisconsin sailors and coastal communities facing the dangers of the unforgiving lakes. Wisconsin divers made history by pioneering new ways to explore shipwrecks. And our maritime historians led the effort to understand them and to protect them for future generations.

– When you see a shipwreck, especially with a lot of the stuff still on it, that’s just really fascinating, especially if you’re diving a little bit of a deeper wreck, and you’re going down the anchor line, and all of a sudden, this shadow appears below you. And as you keep going down, there it is.

– It’s like you’re in a museum of the past on the bottom of the lake. Draws you down there.

§ §

[waves lapping]

– Male Announcer: Funding for Shipwrecks! is provided by the David L. and Rita E. Nelson Family Fund within the Community Foundation for the Fox Valley Region, the Dwight and Linda Davis Foundation Dr. Henry Anderson and Shirley Levine, Robert J. Lenz, A. Paul Jones Charitable Trust, City of Sheboygan, Elizabeth Parker, Sharon and Tim Thousand, the Ruth St. John and John Dunham West Foundation, Ron and Colleen Weyers, Wisconsin Coastal Management Program, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. John J. Frautschi Family Foundation, Trust Point, Focus Fund for Wisconsin Programs supported in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

[boat engine]

– On the Great Lakes, you get these fall gales. And it’s almost like a small hurricane on the Great Lakes. You get caught out in one of those, and you’re in big trouble.

– Things like coal and grain had to be delivered in the fall. And, of course, the gales of November, this is when the worst weather comes to the Great Lakes.

– Green: Shipowners would often press captains to make that last trip of the season past when it was probably prudent to do so.

– There were no weather reports at the time. There was no weather radar. Ships would leave on a November morning, and everybody kind of knew in the back of their mind that there were going to be big storms.

[waves crashing]

– Green: Before you have modern navigation, GPS, and radios, and radar, you really were on your own with your own skills as a mariner. A surprising number of shipwrecks were due to collision, fog, and reduced visibility.

[crowd murmuring]

– Thousands of immigrants traveled to Wisconsin on early wooden steamers, which gave rise to one of the most dreaded causes of shipwrecks.

[ship horn]

– Green: When vessels were switching from sail to steam, fire was a big cause of maritime disasters.

[fire crackling]

The steamer Phoenix, which was carrying immigrants from Holland, they had almost reached the very end of their journey, going to the community of Sheboygan, Wisconsin. And there was a fire that broke out, and the vessel was quickly engulfed, and over 180 people lost their lives. It’s one of the largest maritime disasters here on the Lakes.

– This family bible was found washed up on shore– a symbol of the lost lives and lost hopes for a better life.

– The few individuals that did make it to shore in lifeboats did settle in the Sheboygan area, and their descendants are still there today and hold that story very close.

– Wisconsin’s maritime history stretches back many thousands of years before the first Europeans arrived. In the waters of Lake Mary, in Kenosha county, the Nagle family spotted a piece of that ancient history.

– L. Vrany: Me and my grandma went out in that sailboat there looking for what my dad saw.

– Mr. Nagle: There’s the original piece that was found.

– L. Vrany: We saw it. We picked it up with a pitchfork, and I said, “Grandma, I think this is an Indian dugout canoe.” My grandma said, “Lauren, I think it is.”

– Joyce: And, of course, myself being an archaeologist, I was very interested right away, and went out, checked it out, and sure enough, it’s the front end of a canoe, a dugout canoe.

Looking at it, we decided right away that it was a little bit unusual. There were no metal tool marks of any sort. It looked like it had been charred, and then the interior scraped out, which would mean that it was prehistoric. We put it back in the water.

I called the State Historical Society. They have maritime archaeologists. At that time, it was Dave Cooper and Jeff Gray. And they actually swam through silt and felt their way around to find more pieces. At that point, they took the dugout and all of the pieces back to the State Historical Society for some conservation work. Radiocarbon dating is a great way to date organics, and, of course, a tree is organic. And we just took a sample and sent it off to the lab, and it came back to be 1,860 years old– so nearly 2,000 years old.

– At nearly 2,000 years old, this dugout canoe is the oldest watercraft found yet in Wisconsin.

– We have a tendency to think that people who lived long ago didn’t move around a lot, and it’s just not true. They moved around a lot.

– Grignon: The birch bark canoe is probably a universal boat of the Great Lakes tribes. The roots and the cedar, and everything was available from the environment to make a birch bark canoe. We used to go up into Canada in birch bark canoes, the huge ones, up to Montreal, and trade with the French. The birch bark canoe had to be really sturdy and able to withstand the waves of the Great Lakes.

[birds cawing]

– Off the coast of Manitowoc and Sheboygan lie many of Wisconsin’s oldest shipwrecks. In 1994, a fishing tug out of Two Rivers, the Susie Q, snagged its nets on an object underwater.

– Steve Radovan: They asked us divers if we could retrieve the net for them. The net buoy was floating on the surface. They told us about where it was. We went out there, took a look at it electronically.

– The net had snagged on a shipwreck, sitting upright, with its mast still standing.

– Radovan: And it was a short time after, we sent two divers down to see if they could work on that net. They also wanted to see what it was. They didn’t get much beyond the mast at that very first time. But that mast was a dead giveaway that they had found a schooner.

– A sonar towfish pulled past the wreck, provided the first glimpse of the ship from bow to stern.

– You see the actual shape. The back end is broke down, or the bow is broke down.

[electronic beeping]

[splash]

– More dives gave clues to its identity, which was later confirmed to be the schooner Gallinipper– Wisconsin’s oldest shipwreck.

– Baillod: Turns out, the Gallinipper was built as the schooner Nancy Dousman in 1832. And she was owned by Michael Dousman, who was a fur trader up at Michilimackinac in the eighteen-teens and twenties. He became one of Milwaukee’s largest grain merchants.

– The Nancy Dousman would go on to take part in most of Wisconsin’s frontier industries– beginning with carrying loads of fur to eastern markets. On a return trip in 1833, it stopped at the growing settlement of Green Bay, delivering an essential load of supplies.

– Baillod: There were a lot of goods that you just couldn’t get here. If you wanted anything made of glass, if you want dishware, if you wanted silverware, if you wanted nails to build your house, you had to get that all from Buffalo or Oswego.

– In Milwaukee, new owners cut the ship in two, added 25 feet to the middle, and renamed it The Gallinipper. The ship went back to work, now carrying bigger cargoes of Wisconsin lumber and grain. But its new length made it hard to handle. And in 1854, it was knocked down in a storm and went to the bottom. All of the crew were rescued by a passing schooner. The Gallinipper remains an example of the craftsmanship of early, hand-built ships.

– Baillod: They really were made as works of art. They had beautiful carved figureheads and scrollwork on their bows. Their sterns, their transoms, had beautiful carved artwork on them. And finding a ship from that era, from the handcrafted era, where the men worked the beams by hand, literally carving those ships out of oak. And, one of those ships might take 20 acres of white oak. They would have to level 20 acres of forest to build. The Gallinipper is a prime example of a vessel that you can look at every single piece of wood on there, and it’s all made of wood, just carved by hand by craftsman. There were hundreds of wooden schooners that you could see out on the lake at any one time if you lived in, say, Milwaukee or Sheboygan or Manitowoc.

– When schooners and those early wooden steamers were sailing the Great Lakes, you would see this waterfront here in Manitowoc just chockablock full of those.

– It was such a huge part of Wisconsin’s economy and Wisconsin’s culture. A whole community of people lived there that worked on those ships.

[water lapping, birds cawing]

[upbeat music]

– With 300 miles of shoreline, and a rich maritime past, Door County became the perfect destination for the growing sport of scuba diving in the 1960s.

– Boyd: It was probably one of the first places to really catch on. And the thing that drove people in the direction of Door County was shipwrecks.

– Robinson: And at the time, I lived in the Chicago area and came up here with my club diving, and I was hooked. You know, we were used to diving in quarries or lakes down in Illinois or southern Wisconsin, and now I come up here, and there’s a shipwreck. And boy, I… and eventually, I moved up here.

– The growing popularity of scuba was due– in part– to the efforts of a diver from Wisconsin named Zale Parry.

[studio audience applauds]

– Groucho Marx: How far down can you dive with this rig?

– Zale: With the Aqualung, I dove to 209 feet.

– Well, I admire you, Zale. It must take a lot of courage to go down that deep.

– Thank you.

– I get panicky when the barber puts my head in the sink for a shampoo.

[studio audience laughs]

Isn’t that getting in pretty deep for a young girl like you?

– Zale: Yes, it is, Groucho, it’s the women’s world record.

– Well, congratulations!

[audience applauds]

– Parry grew up on the waters of Pewaukee Lake, and in high school, joined the Sam Howard Aqua Follies as a synchronized swimmer, performing at fairs and other large events. Moving to California, she learned to scuba dive and became a dive instructor.

– Sea Hunt Narrator: Marineland was anxious to have a specimen of this strange fish. But 3,000 pounds of sheer muscle was too much.

[dramatic orchestra music]

– Parry joined the production team of the popular television program Sea Hunt and gave its star, Lloyd Bridges, early lessons in how to dive. She also appeared in many episodes of Sea Hunt, a program that boosted the interest in scuba diving around the country.

– Sea Hunt Narrator: An approaching ship…

– I got interested in diving back in about 1959 from watching Lloyd Bridges on Sea Hunt.

– Lloyd Bridges: Let’s look!

– I was just fascinated by it. So, I looked up in the Yellow Pages in telephone book where the closest dive shop was and went over, and I ended up with a tank, regulator, mask, fins, snorkel.

– Frank Hoffmann would go on to shock the shipwreck diving world by finding the first completely intact wooden schooner– something most experts thought impossible.

– Boyd: I was working summers in Door County as an outboard mechanic, so I went down and introduced myself to Frank because, frankly, I thought he was a charlatan. We’d heard this rumor about this– “Oh, my gosh, an intact wooden ship? That can’t be. And anybody that says so has got to be a fake.”

I went down and find this guy is very, very genuine. In fact, particularly when he looked me in the eye, he said, “Hey, would you like to go out and dive it on Sunday?”

Well, [chuckles] that pretty well settled the matter.

Frank sold his business in Chicago, bought a bar and grill up in Door County, and expanded it with a motel and a little diver’s air station where you can get your scuba tanks filled. And he had a couple of boats, and he started taking divers out to visit this thing because it was a whole new experience. And, boy, we had people come from all over– as far as California and so on– to visit this wreck.

– The wreck was identified as the Jennibel, a Door County schooner that sank in a storm in 1881 while carrying cordwood and hemlock bark– used for tanning leather. All of the crew were rescued.

– Boyd: That was kind of a spark, and people said, “Wow, you can actually find these things intact. And there’s all these artifacts and stuff on them.”

– But the Jennibel was soon broken to pieces in an attempt by treasure hunters to lift it off the bottom.

– Boyd: They made arrangements secretly to raise the wreck and diving at night out there. The location was kept secret. How did they find it?

They had followed us out there with a boat equipped with radar so that we didn’t see them following us out. But, in fact, they were able to locate the wreck. They put two cables under it, ran those two cables up to a single cable, and tried to lift this thing, which is settled several feet into the mud. And essentially, what happened is that they just snapped it in two in the process, and it scattered down into this trench.

§ §

– Remarkably, Frank Hoffman would soon discover another intact shipwreck.

[splash]

It was a mystery ship– one that would change forever the way shipwreck hunters and archaeologists would view the shipwrecks lying in Wisconsin waters.

§ §

§ §

At the time Frank Hoffmann discovered the schooner Jennibel, shipwrecks were not well-protected by state and federal laws. He brought up one of the ship’s anchors and placed it behind his new business in Egg Harbor.

– This was “finders keepers” times in those days. And so, the idea that when you were on the shipwreck, if you didn’t, say, maybe pick up a plate in the galley or maybe even saw off a fitting, but you better bring something up, or you weren’t much of a diver.

– Although treasure hunters had wrecked the Jennibel, Hoffmann’s discovery of an intact schooner shocked the diving community.

– Boyd: People said, “Wow, you can actually find these things intact.” But what are the chances that this will ever happen again?

– Hoffman: Dick Garbowski, fishermen in Menominee, just called me on the phone and asked if I couldn’t free their nets. They got them tangled up in some object underwater.

And, of course, it was– Well, it was in November of ’67. It was cold, miserable day out, but the water was halfway calm. I couldn’t get in contact with any of the other divers in our group in that short of a notice to come up and help us out with the net. So, I had to make the first dive myself.

[suspenseful music, splash]

Going down alone, I wasn’t feeling too well, you know, myself, but it was a job that had to be done. And, of course, our Green Bay waters are dark. Your light fades out at about 60 to 70 feet.

When I did get down to the net, and, of course, then I seen what was down there, and it was an old sailing ship.

Back in them days, we only had pressure cookers with car batteries in them and sealed beam headlights. The pressure cooker that I had, the light kept going on and off. And, of course, visibility was a foot and a half. When the light went out, you didn’t see nothing.

And I did the best that I could freeing the net, cutting the net, and freeing it up.

And after a certain length of time, I knew that I couldn’t accomplish the job myself. And so, then I returned back up to the surface, and I was never so happy to get up on top as I was after that dive.

I knew at the end of that dive that we were on an old sailing schooner. How old exactly, I do not– I didn’t know at that time. But the idea that I knew it was big, and I knew it was beautiful, and it was something that had never been touched before.

I felt the best thing was for me to call in for extra divers, to finish freeing the nets up.

After we had accomplished the job of getting the nets off, we took a tour of the ship itself to see what it was. We found the wheel of the ship, and there was still canvas on the wheel itself. And this was to protect somebody from putting their arm or leg through it if the ship would take a fast turn.

As to the interior of the ship, we found out that it was entirely filled with silt to within about a foot or so of the deck, you know, inside the cargo holds. The cabin area was the same thing. And when the diver would go into the silt to get any articles out from inside the ship, the silt would stir up, and it would hang in the water. And we didn’t realize up or down or sideways. It was like swimming through a bottle of India ink.

– Boyd: That was very exciting because we had no idea what the wreck was. In those days, none of those records and so on were available. There was very little interest in that sort of thing. And so, for the better part of a year and a half, we had no idea what it was.

– Hoffmann’s team of divers brought in a small pump to begin removing the silt and brought up artifacts that gave clues about the identity of the ship.

– Boyd: I brought up a bowl out of the galley, and on the bottom of it is a bunch of embossing on there. And we were able to determine that it was pre-Civil War, and so, this vessel has got to be very early 1840s and ’50s, ’60s. That’s real old stuff as far as Great Lakes shipping is concerned.

– As the divers brought up more artifacts, well-preserved in the cold, thick silt, the media began to follow the story.

– Boyd: We’d gotten just enough artifacts out that this craze was going wild and the idea that, first of all, a totally intact wreck had been found. They don’t know what’s in it. They don’t even know what it is. It’s the “Mystery Ship From 19 Fathoms.” The excitement got so much that all of a sudden, Marinette Marine Corporation, particularly Harold Derusha there, was a big maritime history fan; He essentially gives the project a 60-foot LCM craft equipped with a very large eight-inch diameter salvage pump. We just outfitted this thing for diving. So now, all of a sudden, we have this huge craft to work with.

– After connecting the big pump, divers began removing tons of silt. More artifacts were revealed– frozen in time, on the ship’s last day at sail.

– One big crock came up. There’s a nice picture of it. Had the usual little silt on the top of it, so we scraped it off from. The thing is, is full of what was called a crock cheese, which was a very common staple on ships, and they can put it onto a biscuit and so on. I was a microbiologist at the time, so we took a sample, and by golly, we could still recover the lactobacillus that had formed on it. The thing was still viable in the cheese. And so, we sent it out to the Kraft Foods people. And it turned out it was the world’s oldest sample of edible cheese. “Did I taste it?” is always the question. Yeah, I did, and it was terrible.

[chuckles]

But in talking to people who were familiar with that sort of thing, they said the stuff was always terrible.

In another case, we came up with a couple of ducks. They were pretty much intact. The flesh and so on was on them. The head and so on was missing. These things were prepared for a meal.

That was about the same time that we identified the wreck and realized that the captain and a couple of crewmen had gone down with it. And we got real uneasy about working in that silt down there. As it turned out, there were no human remains ever found on the Clark. They were not on board the vessel.

– The mystery ship was identified as the Alvin Clark: built in 1846 and sunk in 1864.

– Almost a little tornado came dancing across Green Bay and smacked her and capsized her, and sent her to the bottom.

– It’s now thought the ship transported lumber for timber pirates, who cut down trees on government-owned land.

– We’ve gotten just enough artifacts out that this craze was going wild. And all of a sudden, you’re up to the point where you’ve identified it and so on. And gosh, you’ve got this thing. At that time, there was no other known intact wreck. It just seemed like the logical thing would be to bring it up and preserve it. And, of course, Hoffman really wanted to do it at that point. He really had the fever. He almost had dedicated his life to this whole business.

– The first step in raising the ship was to find a way to loosen the masts from the deck and haul them up with a crane. Next, the group figured out a plan to raise the ship itself, using six cables tunneled under the hull.

– Boyd: Where do you buy a tool to do that? We had to invent one. We bent a piece of two-inch aluminum pipe that would match the curvature of the hull. On the end of it, we designed what we called a dredging head.

Attach that on one end of the pipe, firehose on the other, and you wrestle that underwater. You could just slowly push that pipe right underneath the Clark. And this thing would just dredge its way right under following the curvature of the hull. When it popped up on the other side, you tied a nylon line on it, pull the thing back out, and there was a cable waiting from the surface that you then attached to the nylon line. Took six weeks to put six cables underneath that puppy, and that was a real job.

– Hoffmann: A lift barge had to be found. And, of course, Marinette Marine came through once again in locating one for us. They had gotten the steel cables ordered that we were going to put in underneath the ship itself. From this, we used a set of blocks and pulleys and with 24 steel cables going up to the lift barge. The lift barge was positioned over the ship itself.

And on the lift barge, we had four hand-crank winches. For every hundred turns on the cranks, we could raise the ship approximately five inches. It was very tiring on our crew because they had worked so long. Boats would come out to see what was going on– all of the sightseers, newspapermen, television people, and everything else.

No one was allowed onto Cleo’s barge or onto the lift barge itself until they put in their hundred turns on the crank to help us raise the ship. And everybody pitched in.

And it was a tremendous thing, you know, to see hundreds of people out there all helping us work in the final lifting process.

As the cranking came to an end, the ship became visible under the barge. Its bowsprit rose above the water, and the crew triumphantly posed on it [dog shakes off water] as the barge readied to tow the ship to Marinette for the final raising.

[crowd murmuring]

– Marinette Marine closed the shipyard. And there were over 15,000 people that had come down to watch the Alvin Clark raised to the surface. And it was a tremendous feeling. We had dove on the ship for two years. We had never seen the ship itself in its entirety. All we could see was three and four feet. We were amazed just as much as everybody else was.

– Boyd: When that thing hit the surface, and you saw the size of that thing, we just went, “Wow, you know, this is really something else again.”

The thing was all so nice and clean that it was just absolutely amazing. We decided to see how badly it was leaking and we had pumped it out. We slack the cables off, and the darn thing floated. A hundred and five years it had been underwater, and as far as we could tell, it wasn’t hardly leaking a drop.

– As they cleaned up the ship, the divers brought up the remaining artifacts that would tell the story of life on an early schooner. After a long period of kiln drying, the ship was re-rigged, and became a popular tourist attraction.

– Boyd: All of the rigging was put on, the ratlines, the whole business. She looked just like she would sail. And she was floating in this little private harbor called the “Mystery Ship Seaport,” between Marinette, Wisconsin, and Menominee, Michigan. And so, she was a regular museum.

– The Alvin Clark yielded a boatload of maritime information– how the sailors lived, the design and construction of the ship, and much more. But over the next two decades– exposed to the elements– the Alvin Clark began to deteriorate.

– Boyd: What she really needed very apparently, she really needed to be dry-docked and to have a building over her.

– Hoffmann: It’s the feeling of myself and our group that actually we did our job. And it’s now for somebody to come forth and preserve and take care of the ship.

– Frank Hoffmann moved the ship out of the water, but try as he might, he couldn’t raise the funds to preserve it.

– Boyd: And the money for it just wasn’t there no matter what you do or how you tried. And it eventually disintegrated and was unceremoniously bulldozed up and run off to a landfill site in the ’90s.

[regulator bubbles]

– The destruction of the Alvin Clark signaled the end of the “finders keepers” era of Wisconsin shipwrecks. New laws were passed to protect shipwrecks– encouraging divers to visit, but to “Take only pictures and leave only bubbles.” In 1954– 15 years before the raising of the Alvin Clark– a Dutch cargo ship, the Prins Willem V, loaded up in Milwaukee. After taking on a full cargo of Wisconsin products, the ship departed at dusk in strong October winds.

[wind whistling]

Three miles out, the Prins Willem collided with an oil barge. As it began to sink, the coast guard arrived and rescued all of the crew.

[wood creaking]

The Prins Willem came to rest on its side in 80 feet of water. The Army Corps of Engineers declared the wreck a hazard to navigation and requested proposals to remove it.

– Scott Kuesel: The Corps of Engineers assumed that the wreck would have to either be cut up, dynamited, dragged out to deeper water, or raised in order to clear it to the required 40 feet deep.

– Milwaukee salvage diver, Max Nohl, won the bid to clear the hazard and gain ownership of the wreck. He soon discovered that it would be easier to clear than anyone expected.

– This is the gangplank from the Prins Willem V. This was sticking up to 31 feet of the surface. The Corps of Engineers felt that the entire wreck stuck up that high. Max Nohl got the contract to clear it to the required 40 feet, and all he had to do was cut this loose. Took about 20 minutes.

– As a child in the 1920s, Max Nohl became fascinated with the Jules Verne classic 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea. The growing popularity of the open bottom diving helmet inspired many Wisconsin teenagers, like Max and his friend Jack Browne, to build their own. Jack made a rubber suit out of old innertubes and a helmet from a five-gallon paint can, held down with window weights. Jack lent his suit to Max to make a dive into Lake Michigan.

– Kuesel: And according to Max’s writings, years later, he was hooked. He wanted to be underwater whenever he could.

[splash]

– While a student at MIT, Max bought a used diving suit, which he brought home one summer. With the help of his friends Jack Browne and Verne Netzow, he discovered the wreck of the J.M. Allmendinger– a wooden steam barge that ran aground in a storm near Mequon in 1895. After college, Nohl met and teamed up with John D. Craig, a diver and Hollywood adventure-film producer. Craig had secured a contract to work on the salvage of the Lusitania, an ocean liner, sunk off the coast of Ireland in 1915.

– The Lusitania that got us into World War I had been torpedoed off of Ireland in 312 feet of water. And the deepest dive of record at that time was made by a US Navy diver– 306 feet. So, how could they get at the treasures of the Lusitania?

[suspenseful music]

[turning page]

– In the quest to reach the Lusitania, Max Nohl and Jack Browne would team up once again to design and build a revolutionary diving suit. Nohl and John Craig, would volunteer as human guinea pigs, in dangerous experiments, hoping to shatter the limits of how deep shipwreck divers could go and how long they could stay down.

[heartbeat, exhaling into regulator]

§ §

– In their quest to reach the wreck of the sunken ocean liner Lusitania adventure film producer John Craig and Milwaukee diver Max Nohl would have to dive deeper than anyone wearing a standard diving suit had ever gone.

At the time, shipwreck divers breathed compressed air delivered through a hose by a pump on the surface. Dive times and the depth a diver can go are limited by the nitrogen in the air, which accumulates in the blood under high pressure.

– Kuesel: The nitrogen has some ill effects, and one of those is sometimes called the bends. The nitrogen gets into the bloodstream in a liquid form. And if the driver comes up from a depth too quickly without what’s called decompression, that nitrogen returns to a gas and bubbles in the blood supply of the diver. And the worst-case scenario is it kills the diver. And the other was the effects of nitrogen– you start feeling like maybe you’ve had an extra martini or two. “Nitrogen narcosis” is what they call that– drunkenness. And some of the decisions that are made can be fatal.

– While a student at MIT, Max Nohl designed a self-contained diving suit without a clumsy air hose. Nohl decided that air could be supplied by tanks, which opened up the possibility of breathing gases other than regular air. As Max and his old friend Jack Browne set to work, building the new suit, word began to spread about their plans.

– The idea that this guy now claimed he had a revolutionary suit that was self-contained and they were going to go down on the Lusitania and salvage it. Milwaukee Journal picked up on that. And, of course, that kind of story went out on the old wire service.

– Some articles noted that they planned to experiment with breathing helium instead of nitrogen. This caught the attention of Dr. Edgar End, of the Marquette University Medical School. He knew that a diver breathing helium could, in theory, dive much deeper and return to the surface much faster.

– Dr. End had been doing some experiments with helium and oxygen on animals that they had at Marquette University. They had little chamber systems set up, and they were looking at the possibility of using helium.

And so, they teamed up. But how the heck would have they ever tested these things other than maybe doing it in the water, which could have been maybe difficult and risky? How the heck would they have known this thing was going to work ahead of time?

But in 1928, Milwaukee had put in what’s called a recompression chamber because they were seeing a lot of cases of bends. This wasn’t from divers. This was from people that are called “sandhogs.”

[clanging]

– Milwaukee’s “sandhogs” were construction workers digging the deep tunnels for new sewer lines and water intakes. If they came up to the surface too quickly, they could suffer from a case of the bends.

– Boyd: And so, in the old Milwaukee County Hospital, they built a recompression chamber so that these guys could be recompressed, which was the only really successful treatment, usually for the bends.

– Using the chamber, Dr. End designed a series of experiments to test the breathing of helium mixtures under high pressure.

– Boyd: Basically, they said, “Well, we need another test animal. I guess that’ll be us.”

[chuckles]

And they walk into the chamber and, you know, run the, run the tests on themselves.

[valve opens]

– Chief engineer Joseph Fischer sealed the chamber and began to slowly pump in air to simulate 100 feet of water pressure.

[inhaling and exhaling audibly]

As the temperature rose to over a hundred degrees, Max Nohl and John Craig would breathe the helium and oxygen mixture for an hour. To test the limits, Dr. End instructed Fischer to release the pressure 23 times faster than usual– in 2 minutes, instead of 47.

[breathing slowly]

The experiment was a success. Both Nohl and Craig felt fine. With the guidance of Dr. End, Nohl used helium on some test dives and discovered an additional benefit.

– Boyd: Max started to realize that, “Hey, I’m pretty sharp down there breathing this stuff.” It didn’t produce that “nitrogen narcosis” effect.

– British Newsreel Announcer: It doesn’t look much different, but it’s something new in diving apparatus. Its inventor, Max Nohl of Wisconsin, breathes a blend of oxygen and helium, which he claims will defeat the tendency to paralysis under pressure at great depth.

– Now fully confident, Max Nohl attempted to break the world’s record with a deep dive into Lake Michigan.

– Boyd: Not only did he get a Coast Guard cutter to take him out to do this dive, but he gets NBC Radio to cover the whole broadcast live. But when you think about it, despite the fact that it was engineered, thought out, and put together, it was a prototype. It was a jury rig! Nobody had ever done this kind of thing before.

– Newsreel: Down he goes. And he talks from below for broadcasting.

– Nohl: Hello, I’m on the bottom.

– NBC: You’re on the bottom?

– Nohl: I’m on the bottom.

– NBC: Well, wait a minute, we’ll find the depth. What’s the depth there?

– 420 feet

– NBC: 420 feet, that’s a record, Max.

– Newsreel: Over a hundred feet deeper than the previous record, which means that the sunken Lusitania is now within reach of the diver.

– The coming of World War II prevented Max Nohl from diving on the Lusitania, but the helium technology he helped develop would go on to revolutionize deep water diving and shipwreck exploration.

[splashing]

In the decades to come, as breathing helium and other new technologies became more common, treasure hunters threatened to strip Wisconsin shipwrecks of most of their artifacts.

– There was a lot of looting that was taking place. People started going out, and they would entirely salvage all of the cargo, all of the personal effects, so it lost a lot of the cultural value that’s associated with the shipwrecks, that really allow us to tell those stories.

– New state and federal laws would eventually phase out the “finders keepers” view of shipwrecks and bring about a new perspective.

– Tamara Thomsen: That these are special places, places that we should protect and respect, that these are places where not only did people live and work, but oftentimes died because in some cases they’re burial sites– and so to leave the shipwrecks as they were when you visited them so they can be new for the next person that comes.

– Merryman: …moved all this stuff.

– Minnesota diver and maritime historian Ken Merryman continues to hunt for shipwrecks, but with a new purpose: to discover their histories and to tell their stories. For almost two decades, Ken has teamed up with Jerry Eliason to do the often-tedious work of finding wrecks.

– Merryman: It’s not a sport that everybody likes. I mean, you’ve got to be kind of boring people. That’s the bottom line.

[chuckles]

Or you got to have somebody that, you know, you can joke around with and have a good time.

– Jerry: Okay, we’re off.

– On this day, Ken and Jerry are leaving the Port Washington Marina on the Heyboy, a wooden boat that draws attention wherever it goes.

– Merryman: The boat’s a 1947 Owens Cruiser, and I’ve owned it for 48 years.

– Ken and Jerry have identified dozens of wrecks, most of them in Lake Superior.

– Eliason: Isn’t it about 20 Ken?

– Well…

– Aren’t we right around 20?

– Merryman: I think it’s close to 30 now.

– I think it’s 40, isn’t it?

– Is it 40?

[both laugh]

[Merryman imitates auctioneer]

Do I hear 50?

– The team was focused on finding the wreck of the long-sought Pere Marquette 18, a railroad car ferry missing since 1910.

[foghorn]

– There were dozens and dozens of them around the Great Lakes. They would save miles by bringing the railroad cars across on the ship instead of driving completely around the lake. But the majority of their work was in the winter, or they spent a lot more, so the Pere Marquette 18 was chartered out as an excursion boat. Because in addition to railroad cars, it also handled passengers. So, it was used as a party boat out in between Chicago and Waukegan and Chicago and Milwaukee. They’d just charter it out.

– After the ship returned once again to serve as a railcar ferry, the Pere Marquette 18 began its first trip of the season from Ludington, Michigan to Milwaukee.

– Eliason: And there are stories that Captain Kilty told his wife that they wrecked my boat when he first saw it after getting it back because he wasn’t the captain during its charter boat season.

[creaking, waves]

– Five hours into the trip, the captain was notified that the stern of the ship was taking on water and that the pumps could not keep up.

– But it just kept getting lower and lower and lower, even though they dumped off railroad cars. Some places, they’ll say that they dumped all 30 of them. Some places, it’ll say that they dumped half of them.

[staticky ship to shore radio transmits S-O-S]

– One of the first Great Lakes ships equipped with wireless telegraphy, the Pere Marquette 18 sent out a distress message.

– They were saying things like, you know, “For God sakes, hurry, help us.”

– At first, company operators on shore dismissed the messages as fake, the work of a prankster. Eventually, other vessels heeded the call, and a sister ship, the Pere Marquette 17 steamed off to assist.

– And they arrived just in time. The Pere Marquette 18 hadn’t gone down yet.

– With the Pere Marquette 17 standing by, the Pere Marquette 18 continued its slow progress due west. With all engines still running, the captain seemed confident of the ship’s ability to make it. Suddenly, the big ship began to list. The stern sank down, and the bow rose high into the air. Passengers and crew on deck jumped for their lives as the ship quickly sank, stern-first.

[yelling]

It’s now thought that 29 people lost their lives. And even with many witnesses and 35 survivors, the cause of the wreck remains a mystery. Those who might have known the answer– the captain and all of the officers– went down with the ship. To search for a ship, Ken and Jerry use a side-scan sonar that uses reflected sound to paint a picture of the lake bottom.

– All right, so she just tows like a torpedo. This is what we see. You know, if you saw a bright spot out here, you’d be looking for something about that size, you know, for a shipwreck, about an inch.

– Watching the sonar, the team systematically scans a search area in a process they call “mowing the lawn.”

– ‘Cause you’re just going back and forth, back and forth, over that area.

– To pinpoint the search area, Ken and Jerry did a deep dive into the historical record.

– Merryman: We found a report from the wheelsman. All the officers died so he was the only one that had any clue on the navigation of where the ship was. That at a certain time they turned and headed south. They were dumping railroad cars. Then, then the helmsman said, “I got the command to turn toward shore.” So, we just kind of scribed in all the things, and we got a sweet spot. We went back and forth and then said, “Okay, let’s both put an X on the chart, pick our area.” And then, Jerry defined the search grid.

– Eliason: In this case, it was a fortuitous compromise.

[both laugh]

– Yeah, I guess you could call it…

– After just a few passes on their grid, their research paid off as they spotted what appeared to be a shipwreck in about 500 feet of water.

– This is how the wreck lies. This is the bow, and it sank stern first, speared into the mud, and still sits at quite an angle.

[bubbling]

– Dropping a camera and cable the length of a 35-story building, Ken and Jerry captured the first images of the long-lost Pere Marquette 18. The twisted metal and collapsed structures reveal the impact of striking the bottom, nearly 500 feet down. A railroad car remains on board.

– Marge Christensen: Our phone rang around 10:30 one night, and my son said, “Mom, the 18’s been found.”

[laughs]

Wow! We were… really elated. It was the neatest thing. We sat there for quite a while looking, both of us on our respective computers, and some of the pictures that had been posted. And people say– they mention closure. But I can understand it now. We were far removed from the actual experience, I mean, by a few generations, but… So, we didn’t ever feel the sadness of it, but… it was just really a good, good feeling that it had been found.

[splashing]

– Of Wisconsin’s 750 known shipwrecks, the diving community has now found over 200.

– We actually have 75 shipwrecks now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and that’s more than any other state. It’s been a long time coming. And, there’s lots of people that have helped us along the way get to this point where we’re a leader really in the preservation of these resources. So, we can look at each one of the shipwrecks individually, and they all tell stories. So we can learn about the people that worked there, we can learn about the cargoes that were associated with them, what their routes and ports of call were. We can also learn really the immigrant stories. People that not only took ships to come here to Wisconsin, but also were involved with the early maritime trade. And so, when we look at these things as a whole, it’s really an underwater museum. It tells this maritime history, from very early on with Native American craft, all the way up to our latest shipwrecks, which were into really the modern era of freight carrying. Each ship has its own story, each ship association with a port, and that port has its own story. But they all contribute to this overall maritime history of the state.

§ §

§ §

[birds calling, waves crashing voices in background]

– Male Announcer: Funding for Shipwrecks! is provided by the David L. and Rita E. Nelson Family Fund within the Community Foundation for the Fox Valley Region, the Dwight and Linda Davis Foundation Dr. Henry Anderson and Shirley Levine, Robert J. Lenz, A. Paul Jones Charitable Trust, City of Sheboygan, Elizabeth Parker, Sharon and Tim Thousand, the Ruth St.John and John Dunham West Foundation, Ron and Colleen Weyers, Wisconsin Coastal Management Program, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. John J. Frautschi Family Foundation, Trust Point, Focus Fund for Wisconsin Programs supported in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

2WSW0000HDDVDX1_Asel Trueblood_Transcript

– In 1938, Asel Trueblood recorded the story of his life on the Lakes.

§ §

– My father went to the War when I was two months old, and he was killed in ’64 in the Siege of Atlanta. He never come back.

And my mother got married then, you see, to another fisherman. We moved into St. Martin’s Island on Green Bay, and we fished there. I went with him in the sailboat when I was ten years old, and he learned me how to steer the boat.

Well, then I stayed with him ’til I was 15 years old, and I thought, “Now, if I’ve got to serve my life “around this shore here with these little sailboats, “I’m going to ship onto some bigger vessels where I’ll learn something.” So I left him and I went on to the bigger vessels.

And the name of the boat was the Mary Gregory.

Then I went into the schooner Merchant with Billy Olmstead, Captain Billy Olmstead. He sailed these fish traders, you know. Buying fish along the north shore around the islands, Green Bay islands, Green Bay shore, you know.

And then, after I left him, I went into bigger vessels. And they was grainers, and they was iron ore vessels, see, and grainers.

I sailed in a grainer from Chicago to Buffalo three straight seasons in one vessel. And her name was the Guido Pfister, a big three-mast schooner. She carried 67,000 bushels of grain.

And from that time ’til I was 53 years old, I followed the lake.

[serious music]

2WSW0000HDDVDX2_The_Moonlight Transcript

– Shipwreck hunters Ken Merryman and Jerry Eliason have identified dozens of wrecks, most of them in Lake Superior.

– And that is a lot fewer than some in the lower Lakes. But Lake Superior only has one-fifth the number of wrecks per square mile of the other Great Lakes, so…

– In the Wisconsin waters of Lake Superior, Ken and Jerry searched much of the Apostle Islands area.

Off Michigan Island, they found several wrecks, including a wooden ship called The Moonlight. The Moonlight sank in 1903, after a productive career on the lakes. Built in 1874, at Milwaukee’s Wolf and Davidson Shipyard, The Moonlight became celebrated for its speed and its beauty.

When captain Denis Sullivan agreed to race the schooner Porter from Milwaukee to Buffalo, New York, and back, The Moonlight was immortalized in a song sung by sailors around the lakes.

[“The Crack Schooner Moonlight”]

– § Oh, we skirt the western shore §

§ For ahead is Mil-wau-kee §

§ All day and night we’ll drive her §

§ ‘Til the straights are on our lee §

– Nearing Milwaukee, the boats ran into a violent storm, and captain Sullivan and The Moonlight dropped back to the safety of Port Washington. Pressing on, The Porter approached Milwaukee when a sudden squall snapped off its masts. The Moonlight, although the loser of the race, soon reloaded with a cargo of corn and headed back to Buffalo.

Like many Great Lakes ships, The Moonlight suffered its share of misfortunes. During a storm, it was grounded on a Michigan beach, and it took three attempts and several months to set it free.

The Moonlight now lies at the bottom of Lake Superior, 240 feet down. The cold waters preserve the wreck, and the lake’s environment slows the growth of mussels. The parts of the ship are clearly visible, like a gaff, which once held a sail.

Although the wreck is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and lies in deep water, it remains vulnerable to treasure hunters, who might illegally remove its artifacts, like the ship’s bell, buried in iron ore; a lantern and a mast light; a capstan and a wood stock anchor.

When The Moonlight sank with a heavy load of iron ore, it crashed hard on the bottom, and the hull split open. But the wreckage reveals many secrets about how it was constructed and also shows a big change that was made.

As the age of sail came to an end, The Moonlight suffered a fate common to many large sailing ships. Its masts were cut down, and its big bowsprit removed. It was rebuilt as a schooner barge and towed behind a steamer.

The Moonlight’s last voyage began by leaving the dock at Ashland with a heavy load of iron ore.

While under tow by the steamer Volunteer, a seam on The Moonlight opened up, and it began taking on more water than its pumps could handle. Because it sank slowly, all of the crew were able to get onboard the Volunteer. And then, The Moonlight, once known as “the Queen of the Lakes,” slid to the bottom, where it lay until discovered by Ken Merryman and Jerry Eliason.

TUESDAY, NOV. 30, 2021 | 1HR 29M 22S

Shipwrecks!

On the bottom of Wisconsin’s Great Lakes lie the wrecks of over 700 ships. Each one tells a story about the state’s maritime history; the mariners that worked on them; the industries and communities they served and the dangers of the lakes. Shipwrecks! tells a story of exploration, and takes viewers below the surface to an underwater museum of marvel. Photography for banner and signature show image by Andrew Orr.

Donate and receive a thank-you gift

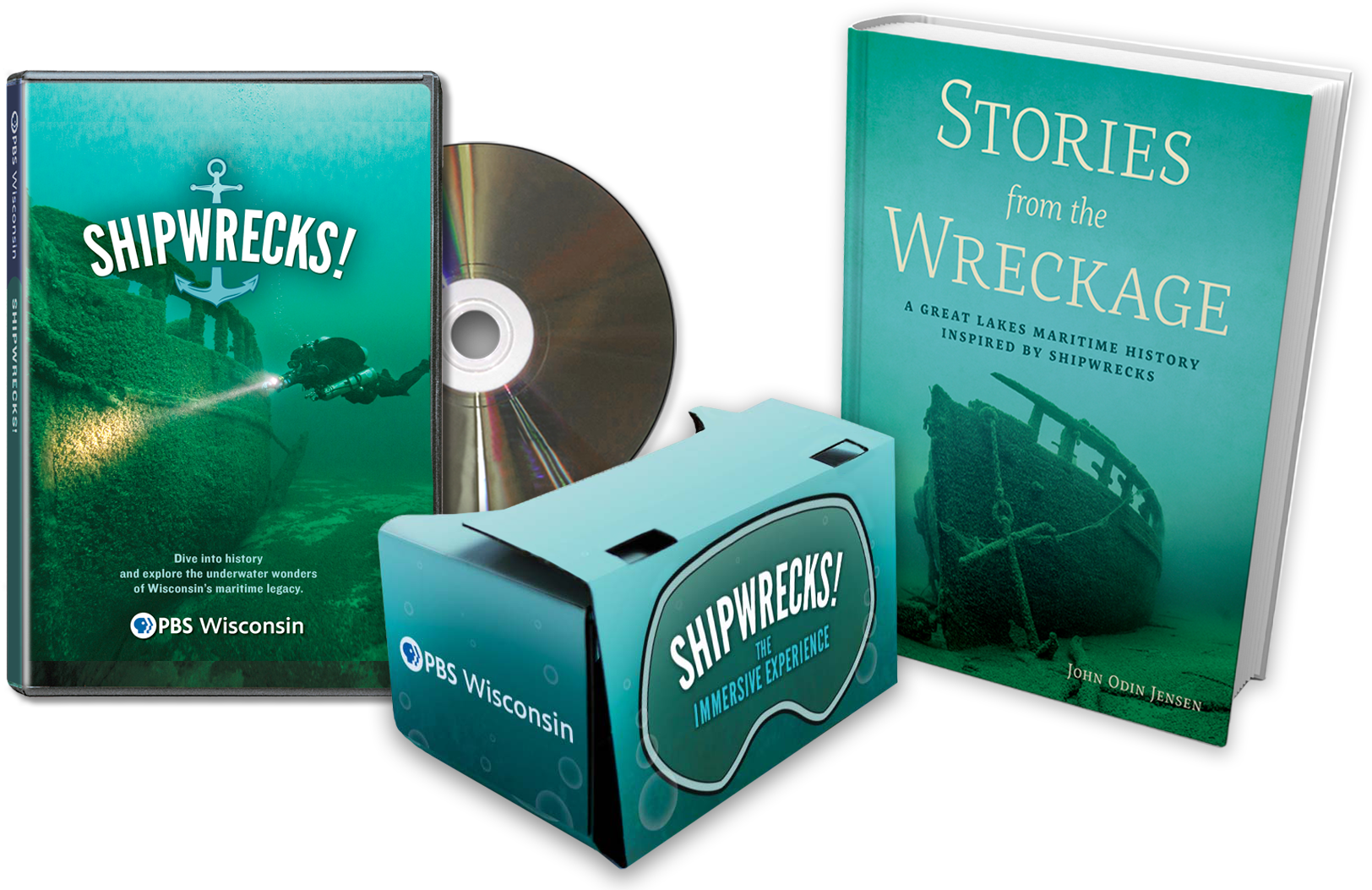

When you make a donation, you can receive Shipwrecks! related merchandise as our way of saying thanks for supporting PBS Wisconsin. Show premiums include a complete DVD of the program, the book, Stories From the Wreckage (2019), published by Wisconsin Historical Society Press, and a virtual reality (VR) viewer to explore three different Shipwrecks! digital immersive experiences. Click to enter the pledge cart, then search “shipwrecks” or use the “Search by Program” drop-down menu.

The SS Wisconsin was a packet and passenger steamer that sank off the shores of Kenosha, Wisconsin, on October 29th, 1929. Shipwrecks! The Immersive Experience is a collection of three experiences that offers you a chance to explore the SS Wisconsin’s history through multiple lenses. The 3D models were generated in partnership with the Wisconsin Historical Society and the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery by using a combination of extensive research and lidar scanning methods.

To navigate the experience in a cardboard VR viewer, please refer to the instructions here.

SS Wisconsin: 360 Dive

Dive down to the site of the SS Wisconsin shipwreck in this immersive, underwater 360-degree video.

SS Wisconsin: The Sinking

Explore a recreated model of the SS Wisconsin on the night it sank, listen to survivor accounts, and discover the events which led to its sinking.

SS Wisconsin: Shipwreck

Dive into this interactive, exploratory tour of the SS Wisconsin in its current shipwrecked state. Investigate the shipwreck and discover underwater footage inside this historic site.

The Legend of the Lost Emerald

History, legend, and maritime archeology align in The Legend of the Lost Emerald, a new educational video game. The game gives students in 4th-6th grade the opportunity to use the tools, practices, and skills associated with maritime archaeology to locate and dive for shipwrecks on the Great Lakes. Learners will start with a mystery and use historical inquiry skills to uncover the real treasure —the stories behind the legendary shipwrecks. The game is the result of a partnership between PBS Wisconsin Education, University of Wisconsin Madison’s Field Day Lab, Wisconsin educators, Wisconsin Sea Grant, Wisconsin Historical Society, and the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction.

Funding for Shipwrecks! is provided by the David L. and Rita E. Nelson Family Fund within the Community Foundation for the Fox Valley Region, the Dwight and Linda Davis Foundation, Dr. Henry Anderson and Shirley Levine, Robert J. Lenz, A. Paul Jones Charitable Trust, the City of Sheboygan, Elizabeth Parker, in memory of George S. Parker II, Sharon and Tim Thousand, the Ruth St. John and John Dunham West Foundation, Ron and Colleen Weyers, the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the John. J. Frautschi Family Foundation, Trust Point, Ellsworth and Carla Peterson Charitable Foundation, the Focus Fund for Wisconsin Programs, supported in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

Funding for the Legend of the Lost Emerald is provided by the Floating Eyeballs Family Fund, the David L. and Rita E. Nelson Family Fund within the Community Foundation for the Fox Valley Region, the Dwight and Linda Davis Foundation, Dr. Henry Anderson and Shirley Levine, Elizabeth Olson, Robert J. Lenz, the Wooden Nickel Fund, A. Paul Jones Charitable Trust, the City of Sheboygan, Elizabeth Parker, in memory of George S. Parker II, Sharon and Tim Thousand, the Ruth St. John and John Dunham West Foundation, Ron and Colleen Weyers, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program, Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, Wisconsin Sea Grant, the John. J. Frautschi Family Foundation, Trust Point, Ellsworth and Carla Peterson Charitable Foundation, the Timothy William Trout Education Fund, a gift of Monroe and Sandra Trout, the Focus Fund for Education, and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us