Q&A: Stanley Nelson, director of Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool on American Masters

January 30, 2020 Leave a Comment

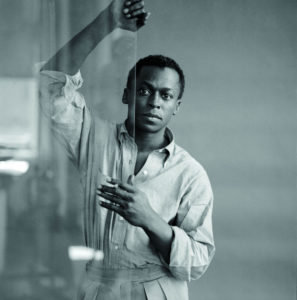

Miles Davis: Horn player, bandleader, innovator. Elegant, intellectual, vain. Callous, conflicted, controversial. Magnificent, mercurial. Genius. The very embodiment of cool. The man with a sound so beautiful it could break your heart.

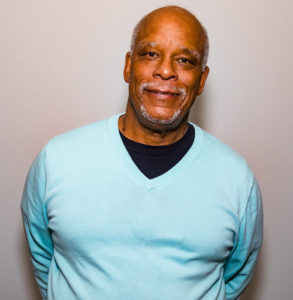

Stanley Nelson, a PBS favorite whose documentaries have appeared on Independent Lens, American Experience and American Masters, presents a film more than 15 years in the making. Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool premieres on American Masters 8 p.m. Tuesday, Feb. 25.

Stanley Nelson, a PBS favorite whose documentaries have appeared on Independent Lens, American Experience and American Masters, presents a film more than 15 years in the making. Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool premieres on American Masters 8 p.m. Tuesday, Feb. 25.

With full access to Davis’ estate, Nelson sought to show the man behind the legend. The film features never-before-seen footage, including studio outtakes from his recording sessions, rare photos and new interviews.

Read on for our exclusive Q&A with Stanley Nelson!

Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool premiered at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival. The screening marked Nelson’s tenth Sundance premiere in 20 years, the most premieres of any documentary filmmaker.

Two of Nelson’s recent films, Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Black Colleges and Universities (2018) which chronicled the 150-year history and impact of HBCUs, and The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution (2016), the first comprehensive feature-length documentary portrait of that iconic organization, broke audience records for African American viewership on Independent Lens and trended on Twitter.

“Every film is approached differently,” says Nelson. “You have to figure out what the story is and the best way to tell it. I and everyone else involved looked at it with this real privilege, to be able to tell the story of Miles, to have the freedom to tell it in a way that we saw fit. We’re trying to figure out inventive ways to tell the story that does Miles justice. I hope we did that.”

What are some of the factors that made Miles Davis so iconic?

So many things. One, being a great musician; and two, for being revolutionary in the way he looked. As some people say in the film, Miles was just beautiful. He had these movie-star looks to go with the other things that were happening.

Musically, Miles was at the forefront of music for over 40 years. Nobody else played with both Charlie Parker and Prince. That’s Miles. He was not only part of the evolution of jazz; he spearheaded the evolution. So many times, Miles changed, and the music changed with him. That’s one piece.

Musically, Miles was at the forefront of music for over 40 years. Nobody else played with both Charlie Parker and Prince. That’s Miles. He was not only part of the evolution of jazz; he spearheaded the evolution. So many times, Miles changed, and the music changed with him. That’s one piece.

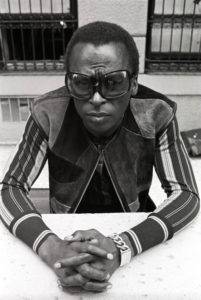

But he also became very popular in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, and he was an icon offstage. Miles wore the best clothes, had his suits tailored, had shoes made, drove Ferraris and Lamborghinis. He demanded the best of everything – which was, in some ways, trendsetting when you think about this happening at that time.

Everybody who knew or played with Miles talked about his presence. When Miles was in the room, you knew he was in the room. A lot of this was just effortless. That’s who he was. It wasn’t that he was trying to be anything; Miles was just Miles, and we wanted to give that sense.

How did this film change in the 15 years between your initial American Masters proposal and the start of production?

The real change is probably that I became a better filmmaker! I had 15 more years of experience. I took more risks, structured things differently. And my reputation had grown, so we were able to get amazing people. The film only got better.

What kinds of nuances did you know you had to get right?

Miles is a very complicated individual – so complicated, in so many different ways. That’s one of the things that made the film work. Any time you do a film about music, there’s a balance between the personal and the musicianship. We wanted to get a sense of Miles’ music, but also about his life offstage and who he was when he wasn’t on the bandstand. Trying to get that balance right.

Some of those complications came out of his personality. There’s a scene where he’d just recorded Kind of Blue, which becomes the biggest selling jazz album of all time, and he takes a beating outside a club from a cop who assaults Miles because he can.

Those kinds of things impacted who Miles was. But musically, he has some of the most beautiful and tender music that’s ever been recorded. Those dichotomies are what make him so interesting.

Davis outside his home, 1969

To some people, profiling a person who has died is easier than working with someone who is still living. What would you say on that front?

I will probably disagree. I would have loved for Miles to be living; I think it’s a lot easier to interview people who were living. Once you get that cooperation, you can interview them about their lives.

It would have been incredible to have Miles to be part of this tribute. I think the complication comes in when you’re trying to make someone come alive who’s passed away. One of the things we did was use his autobiography; we have an incredible voice actor – Carl Lumbly – reading or “playing” Miles. So we do give his view and opinion about his life throughout the film.

Did Miles’ autobiography help give you that thread to follow?

I think we used it more as kind of a color commentary so Miles could reflect on his own life. We also used four or five other biographies to help structure the story.

But also, the great people who played with and knew Miles: Quincy Jones, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, George Wein from the Newport Jazz Festival. Carlos Santana… they’re all part of the film.

How did you find more material from his earlier career, especially when you were unsure if these assets existed?

We knew a couple things existed. We just looked everywhere. Miles went to France in 1949 and after that, he had this great love for Europe, so we looked everywhere we could. If we saw in a book that a photographer had taken one picture of Miles, we contacted that photographer or their estate, knowing that they probably took not one picture but 20. We’d get to the estate, see what else they had.

We probably had something like 4,000 pictures onstage. We wanted to find pictures OFFSTAGE. We just went back and back and back.

One of the things that would always come up when we screened the film was people saying, “I’ve never seen so many pictures of Miles smiling! How did you get those?” Well, Miles did smile, and there are pictures of it. It’s just a matter of digging, from the first day of production to end of production. We’re just trying to find as much as we possibly can.

Wealth did not protect him from the effects of racism. Could you talk about the influence of race in his life?

One thing we found was that this film isn’t just about Miles, this extraordinary musician, but America: race in America, and so many other things.

Miles made this unique life. He grew up very wealthy, especially for an African-American in East St. Louis. His father was a dentist who made a fair amount of money. He still had to deal with that racism that everyone had to deal with, especially coming out of East St. Louis in 1926, when he was born.

Any particular elements to consider when you’re releasing a film for both small-screen viewing and theaters?

Not really. The main thing were technical pieces – images blown up 1000 times to be seen on the screen, doing some things with 5.1 surround sound coming from the back of the theater. Technical stuff. Besides that, it’s pretty much the same film. We’re conscious of the fact that when you play a film in a theater, you have to be a little more careful with every shot, how it looks, and the sound. I think the film looks incredible.

What do you think Miles would make of the times we’re in now?

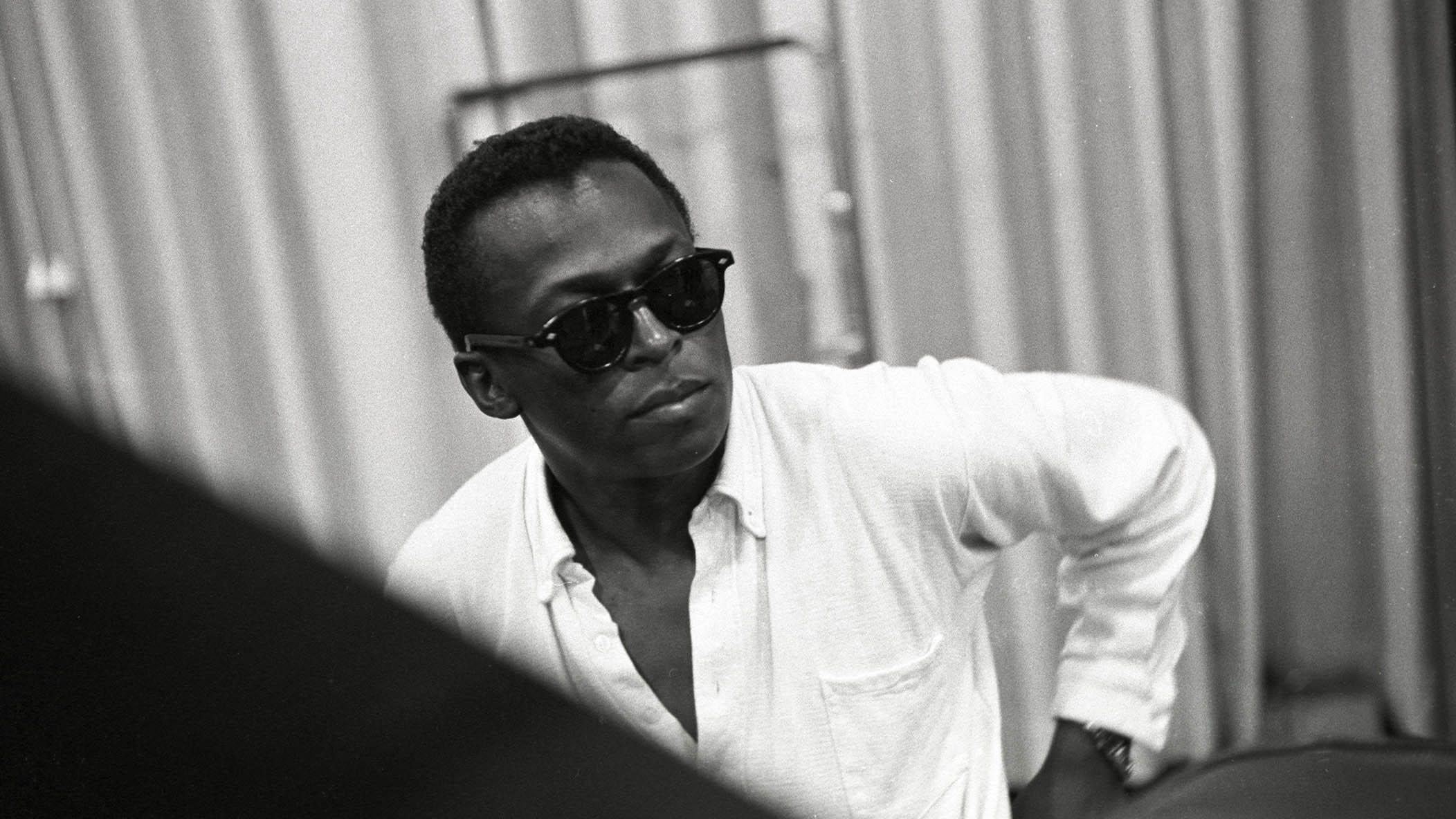

North Sea Jazz Festival, 1991.

Miles was always at the forefront. When he passed away, he was working on a hip-hop album called Doo-Bop. So I don’t know if he was ahead of the times, but expanding.

That’s what made Miles. That’s what he lived for. He never even listened to his old records; his son says in the film that Miles didn’t even have his old records in his house. Until the last year of his life, he didn’t even play some of those old tunes that people loved, from Kind of Blue. He had left it behind; he kept going forward.

There’s a great clip in the film of Miles playing with Prince at Paisley Park. For more than 40 years, he changed music. And it’s not just jazz; Miles wanted to do a rock album, and came out with Bitches Brew, which sold over 400,000 copies in the first month or so it was out. Miles is always one step ahead.

Who knows where Miles would have been. He was always ahead of his time. It wasn’t like he looked around and said, “Oh, let me copy what’s going on.” Somehow Miles had this sense of how to push the music forward. I think that’s what Miles lived for.

Music Documentary American Masters African-American Jazz African American History Month Miles Davis

Passport

Passport

Follow Us