[rain falling]

[thunder crashes]

Abuse, neglect.

What is wrong with me?

[thunder claps loudly]

I mean, why does the brain change?

Significant cognitive and emotional disability.

The mother didn’t show up and your father didn’t show up.

The trauma that they’re enduring just seems to be more severe and more long-lasting.

[police sirens]

Never said, “I’m sorry.”

[woman on the verge of crying]

I am still working through things that happened to me when I was 10.

There’s ghosts in the nursery.

I literally didn’t know what to do.

People say, “Well, you won’t have enough time.”

If we could go back in time maybe…

That’s all we have.

[woman chokes back tears]

I don’t think giving up is really an option.

There’s not enough apologies that one could give to say, “I’m sorry.” Sorry…

[echoing “Sorry, sorry, sorry”]

Funding for Not Enough Apologies: Trauma Stories was provided by Focus Fund for Journalism and Friends of Wisconsin Public Television.

[door opens]

[hand cuffs clink together]

All rise.

[murmuring in background]

Judge Everett Mitchell:

So, much pain, so much pain, so much brokenness.

[sighs]

Narrator:

Dane County Juvenile Court judge Everett Mitchell says when he first took the bench in 2016, his days would often end in tears; his own tears.

Judge Everett Mitchell:

As I started listening to these children, and reading their stories, and letting them talk to me, I started realizing, like, there’s been nobody in their lives. And every adult that’s been in their life has caused them more and more pain.

Narrator:

Mitchell presides over cases of children who’ve been removed from their homes for dangerous circumstances including abuse and neglect, and cases where children are charged with the juvenile equivalent of crimes.

Judge Everett Mitchell:

At the onset, very traumatized children who experience all sorts of trauma from removal of home, abuse, neglect. It’s not always clear that they’re able to get the resources and the help they need to process all that pain. So, it starts with emotional outbursts and those emotional outbursts turn into disorderly conducts.

Narrator:

Mitchell says he sees a steady progression of the same juveniles catching adult criminal charges. He calls it ‘the child welfare-to-adult prison pipeline.’

Judge Everett Mitchell:

Alright, you’re gonna take the handcuffs off.

Narrator:

On this day, the courtroom door opens to a case in point. Bailiffs bring in a boy held in the juvenile detention center who looks much younger than his 16 years. The judge orders the boy’s handcuffs removed. It’s an effort, he says, to try to change what it’s like to be a child in the system.

Judge Everett Mitchell:

We know these children are traumatized. We knew that they were in pain. It made no sense to indiscriminately bring them into the courtroom in handcuffs.

Youth:

Yes, sir.

Judge Everett Mitchell:

Doing alright?

Youth:

Yeah.

Judge Everett Mitchell:

Better today?

Youth:

Yeah.

Narrator:

Long before he appeared in this courtroom, the boy lived a life of relentless adverse childhood experiences. In the child welfare system since the age of five, first as a victim of 23 reports of physical abuse, neglect, sexual abuse, living in institutions since he was nine. Group homes, foster homes, treatment centers, juvenile prison. More than 30 placements. “I don’t have anybody,” he told a social worker.

A court transcript reads, “At the age of 10-years-old, he could not understand why his mother would not want to see him.” It says, while living in a foster home, the boy’s mother told him she was coming to visit. Testimony showed he walked around for two days with his backpack, looking out and watching for his mother to come and visit with him. But she never showed up.

Judge Everett Mitchell:

And he wasn’t given treatment.

Narrator:

And now, he’s before a judge with his own public defender sitting next to him in court.

Benjamin Gonring:

I don’t think that anybody entered the world predisposed to sell drugs or steal cars necessarily in the nature versus nurture debate. How did that 12-year-old who may not even be able to touch the ground with his feet. How did they end up in that chair?

Narrator:

As children become teenagers, criminal charges can amass, as in this case. State Representative Evan Goyke plainly connects trauma to incarceration. State statistics show 98% of incarcerated youth have experienced trauma.

Evan Goyke:

The vast majority of juveniles that are in custody tonight had some kind of child welfare intervention when they were younger, likely where that trauma was experienced.

Narrator:

For his part, Mitchell sends children to the state juvenile correctional facilities sparingly. In fact, the judge ordered the boy before him here removed from Lincoln Hills. When the teenager wrote to him complaining about repeatedly being jumped and beaten up at the prison.

Judge Everett Mitchell:

Because he was just getting beat up too bad. I brought him here the first time. And nobody showed up from his family to take custody of him.

Evan Goyke:

There are a lot of juveniles that have been incarcerated at sub-standard facilities and we see the evidence through the high recidivism rate. We see that that program doesn’t work by the fact that they continue to engage in criminal and risky behavior. If the facility was working, that number would be lower.

[police sirens]

Narrator:

And yet, what to do in the face of continued criminal and risky behavior like the alleged behavior of the 16-year-old before Judge Mitchell? This police pursuit video shows a chase and crash on a Madison highway in February of 2018. According to prosecutors, the teen before Judge Mitchell was the driver of the stolen car involved. As a result, prosecutors in court that day told the judge they deemed the juvenile a danger to public safety.

Prosecutor:

I think that the safety of the community should be of paramount consideration here and that at this point, we have enough of a track record just in the recent months that every time we have released him, we have had new victims. We’ve had new crimes.

[police chatter on radio]

Narrator:

There is conflict between acknowledging a person’s traumatized background and holding them accountable for their actions, especially when those actions can be crimes. Mental health police officer Andrew Muir confronts deep trauma in the communities he serves.

Andrew Muir:

We see horrible things. We see horrible abuse. We see horrible neglect. We encounter some kids with really profound traumas at such an early age that it impacts brain development, let alone their relationship with almost anyone. The catch 22, if you will, for law enforcement and being trauma-informed is that there’s only a certain extent to which we can compensate for that, based on, sort of, our very nature and what we exist for.

Narrator:

That being to protect and serve public safety.

Officer:

An on-call therapist… see if we can…

Narrator:

Prosecutors in juvenile court lamented that every time the boy before Judge Mitchell was released, he committed new crimes. One new crime landed the 16-year-old in court again.

Judge:

Actually, this child …

Narrator:

This time in adult court on felony charges.

Judge:

Count one is a serious charge: attempted first-degree intentional homicide, use of dangerous weapon. If convicted with the enhancer, defendant faces 65 years in prison.

Narrator:

Judge Mitchell says this case that started as a child in need of protection and services leaves him broken.

Judge Everett Mitchell:

This is to me like the worst CHIPS case ever. You know, because he’s alone. And not only is he alone now; now he’s alone facing adult consequences for some of the choices that he got involved in with some of his friends. He falls into this unique place where I don’t think all of his needs have been taken care of and I know all of his treatment needs have not been addressed and there’s not enough apologies that one could give to say, “I’m sorry for … “your mother didn’t show up “or how your father didn’t show up, “or how families didn’t show up or the times in which you were abused in these places.”

Narrator:

Even as he presides from the bench, Mitchell relates to the children of trauma who come before him.

Judge Everett Mitchell:

Part of my patience for these children is, you know, that was me. Every last one of them. I grew up you know, you know, protecting my sister from an abuser for 12 years. I grew up being abused myself sexually and I know what it’s like to be locked inside of yourself and so gone and so confused and so angry.

And so, I tell the kids all the time, “I’m not your judge. I’m not here to judge you. I’m here to show you that I’m your reflection. Whatever you see in me, you can be the exact same thing because some of you are smarter than I was. You’re a survivor. You have power that you just have not even began to tap into. So, if you think I’m special then remember that I’m just your reflection.”

Benjamin Gonring:

If we could go back in time maybe and kind of start when these kids were younger and use that model of:

not, “What’s wrong with you?” but, “What’s happened to you?” If that would have been the mantra of when these, my clients, now who are 12 and 13, were 4 and 5, I don’t think we’d be where we are right now.

[dogs barking]

[wind blows sharply]

Reyna Saldaña:

I was supposed to be in prison. And I’m not. My mom struggled a lot in her life with a lot of drug abuse. I think I started kind of falling apart a little bit, trying to find some connection.

Narrator:

Reyna Saldaña says she tells her personal story so people can understand what happens because of trauma.

Reyna Saldaña:

I was sexually abused when I was younger, before I was adopted and then, again, after I was adopted.

Tim Grove:

The prevalence of the occurrence of kids who experience overwhelming unsupported stress is far greater than all of us would want to appreciate.

Lynn Sheets:

A child who’s been traumatized may have that kind of fight, flight, or freeze response. So, the fight are aggressive external behaviors. So, they may be impulsive in class, they may act out, they may approach others and be physical, and it may be outbursts. That’s kind of externalizing. Some of those kids can have the flight, where they withdraw.

Reyna Saldaña:

Shut down was always the biggest thing. I shut down and… a lot and I — This wall that I built was an aggressive one. I would go into a room that was empty and I’d pretty much demolish things. I’d have people that would block the door, they’d corner me. If they’d try and get me to not leave, and then, I would have an outburst. And they would be like, “You’re hurting people. You’re destroying things.”

Narrator:

Today, Reyna finds healing in riding and caring for horses. As a child, she describes feeling confused and alone.

Reyna Saldaña:

Yeah, ’cause I would try to do something good, or like… And then, it would just all come crashing down, as soon as I had, like, one outburst.

[heels click on floor]

Narrator:

Dr. Lynn Sheets is Director of Child Abuse Programs at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin. She says in addition to fight or flight, which Reyna exhibited, there’s another typical response to trauma.

Lynn Sheets:

Then you have this freeze that might be hard to recognize because sometimes it’s somebody who’s dissociating. Basically, they’re no longer with you, as far as they may be looking at you, but not really responding.

Narrator:

Alisha Fox says she remembers that feeling.

Alisha Fox:

When I was 14, it was bad. I’d get flashbacks, nightmares. I would space out. I’d sit in class and four hours later, I’d still be in the same seat. Like, “Oh, I was supposed to go to lunch. Like, I guess that didn’t happen.”

Narrator:

Experts in trauma say these kinds of behaviors often result from what are called “adverse childhood experiences” or ACEs for short. They are specific childhood traumas now recognized as resulting in toxic stress that damages the brain.

Benjamin Grove:

There are physical impacts. There are neurophysiological impacts. There are social and emotional impacts that are produced. Tim Grove is chief clinical officer at SaintA, a child welfare agency in Milwaukee. He says physical and psychological impacts are worse the more ACEs a person has experienced. Ten such adverse experiences are measured to result in a score ranging from low to high. Surveys find that 58% of Wisconsin adults report growing up experiencing at least one ACE. 14% have four or more. Alisha Fox reports an ACE score of nine.

Alisha Fox:

So, when I was four to fourteen, I got sexually-abused and raped by my father for 10 years. And then, after that, I was diagnosed with severe PTSD, and in and out of mental hospitals, and suicidal at times.

Narrator:

Alisha says she recounts her painful past without tears because today she is strong, a survivor.

Alisha Fox:

C’mon.

Benjamin Grove:

We see kids who have PTSD outcomes or trauma outcomes that are similar to what Vets experience after three tours of duty.

Narrator:

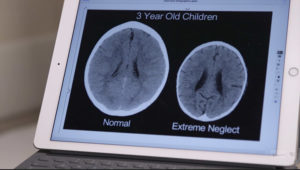

The impacts of even extreme neglect can be seen on brain scans.

Lynn Sheets:

What we have here is a normal child here on the left, and a child here on the right who has experienced extreme neglect. And so, what you can see here is the obvious — that head is much smaller. The reason why is that it’s just the brain itself is smaller.

Narrator:

Abuse that results in the fear response causes additional harm.

Chuck Price:

Your brain then is constantly dispersing cortisol all the time which it’s meant to do that for short periods of time. But if it’s constant, it impacts the brain.

[keyboard clicking]

Narrator:

Waupaca County Health and Human Services Director Chuck Price doesn’t see the effects on a CAT scan, but in the struggles he sees within families.

Chuck Price:

Your neural pathways get set on certain ways and if you’ve been raised in an environment of — of a lot of trauma or adversities or it’s consistent and constant, you’re going to be set up more in survival mode where everything is “fight or flight.” And, “How do I — How do I protect myself?” and the brain sets up pathways like that.

Tammy Fry:

I used to be, like, a bad kid. But that’s only because how I’ve been treated. I’ve never been treated with love or been taught what’s right. I never been… I never had, like, the mother and father that I should have.

Narrator:

Tammy Fry has her own high ACE score and has worked through her teenage years to control her angry outbursts.

Eileen Fredericks:

She had so much trauma with her mom dying, and then her being sec — or, you know, abused by her father, and then being adopted by a biological aunt.

Eileen Fry:

My mom passed away in a car accident when I was three-and-a-half. And then, I lived with my dad. My dad, he was abusive. Then my aunt took me in. She said that she couldn’t handle me when she locked me in my room. As, like, like, she treated me basically like an animal. And then, after that she said she couldn’t handle me and put me into foster care.

Narrator:

Like many children of trauma, Tammy ended up in the system. The child welfare system and then the juvenile justice system.

Eileen Fredericks:

I see this with a lot of kids. It’s like they kind of give up where they just feel like, “I’m going to test everybody to see if everybody is gonna give up on me.” And then, the testing does lead to everybody giving up because it’s very difficult.

Narrator:

For her part, Reyna Saldaña says she could tell people around her had all but given up, only adding to her pain and isolation.

Reyna Saldaña:

I always thought people always saw the bad before they saw the good. Like, I could never do anything right. So, as a kid, I guess I felt really trapped, you know, like, where… like, who could understand that, you know? And there wasn’t really anybody, you know. So, like…

Narrator:

Isolation and sadness and anger often not cured by being removed from home.

Tammy Fry:

In foster homes, like, they’ll just put you in there with anybody. They don’t care. So, like, if you got anger issues, or depression, anxiety, or any other thing, like, they’ll just put you in there with somebody else. Like, because I’ve always gotten into fights so that’s why I’ve been bounced around.

[traffic noise, opening a car door]

[opening creaky screen door, knocking on door]

Tina Czappa:

Most foster parents are really good and they’re really loving and they want to open their home and their family. But, you have those moments where it’s hard for you to receive that kind of love and support because you think, “Okay, your entire life is mostly filled with the abandonment and the rejection.”

Alisha Haase:

I mean, I often ask people, Think about how you would feel, as an adult, if I walked into your home and said, “You have to come with me. I can’t tell you very much about where we’re going. I don’t know when you’re going to see your mom and dad again. You’re gonna leave your school. You’re gonna leave your friends. You’re gonna leave your family and I don’t know when you’re going to see them again.”

Tina Czappa:

At age one, I was removed from my mom and her significant other. Trauma is so prevalent and so highly-prevalent in foster youth because that’s usually why they enter into foster care.

Tim Grove:

One of the hard parts about being in foster care is often kids move two, three, four, or five times.

Pat Snyder:

These kids already are going through, probably, neglect and abuse at home. So, there’s a couple of ACEs or traumas. Now suddenly, they’re removed from the home they know and then put into another home. We’re finding that the trauma builds up and continues.

[conversation echoes off ceiling]

Narrator:

State representative Pat Snyder worked on 11 Legislative foster care bills signed into law in 2018.

Pat Snyder:

Every single one…

Narrator:

Including provisions increasing incentive funding to retain foster homes and encourage permanent homes. He says the need is high for more placements.

UW-Whitewater social work major Tina Czappa formally advocates for such bills in her leadership role in a statewide Youth Advisory Council made up of current and former foster care children. She says after entering foster care at age one, she moved repeatedly between her biological family and foster homes including emergency placements due to abuse and neglect.

Tina Czappa:

They didn’t really have places that they knew where they were going to put me. In their eyes, like, there’s really a struggle, a shortage of foster home placements.

Narrator:

The problem of having enough placements increasingly plagues those responsible for making that decision.

Judge Shelley Gaylord:

What do you think you’re working on that’s going right?

Narrator:

Like Dane County juvenile court judge Shelly Gaylord, presiding here during a hearing concerning a child in a residential care center. Gaylord says she likes to accentuate the positive and give children the first chance to speak.

Judge Shelley Gaylord:

We’ve heard from many children who’ve come through the system as foster home placements talk often about how they feel like they don’t get a chance to talk and when they do, they feel like nobody hears them.

Narrator:

The girl in court appears by telephone, updating the judge about how she’s working through her trauma that resulted from extreme abuse at home.

Girl:

I’m going to sessions a lot more. And I’m talking more about my trauma history

I think we’re all in agreement that the types of trauma that kids are enduring and repeated trauma that they’re enduring, it just seems to be more severe and more long-lasting.

Narrator:

The reason this was a phone hearing is because the child was at a treatment center that’s out of state, 400 miles from Wisconsin.

Eileen Fredericks:

I think people would be concerned if they knew that right now our options are so limited that we’re sending kids out of state. We used to have a lot more options for kids. And I feel like things have just — over the past nine years I’ve been here — just gotten worse and worse in terms of foster homes, group homes, treatment centers, all of them. Those options have kind of gone away.

Narrator:

From 2018 into 2019, Wisconsin placed more than 100 juveniles in out-of-state residential care centers in 17 states, placed there because the children have such high treatment needs they can’t be maintained in their own communities with existing services.

Judge Shelley Gaylord:

When you have higher needs and fewer resources, that’s a perfect storm.

Narrator:

A different Dane County child placed out of state talked with us about being so far from family at a treatment center in Arkansas. Her parents did not want to show her identity.

Girl:

I want to go home. I really do.

Narrator:

This 14-year-old Wisconsin girl was being treated at Mill Creek Behavioral Health Care in a small town an hour south of Little Rock.

Do you know why you had to be sent here instead of staying there?

Girl:

Because none of the other facilities would accept me in Wisconsin.

Benjamin Gonring:

The thing that was really bothering me and the reason, I think, I was most happy to have you come and shine a light on this is this idea that we’re… Things have gotten to a point where we’re sending kids hundreds of miles away from whatever supports they have, which are not great, but they’re still the most important supports in that kid’s life. And the idea that we’re sending them 500, 900 miles away was just unconscionable to me.

Narrator:

Hundreds of miles from home, the girl in Arkansas and the girl appearing by telephone in court where her biological parents had their say.

Attorney:

On behalf of the father, he continues to object to her being placed out of state. He thinks she’d be better off in Wisconsin closer to her family.

Narrator:

But it was due to extreme abuse by her family that authorities were forced to remove the child from her home. The child’s artwork fills the office walls of her attorney, who helped guide her care. What happened to her resulted in the need for high-level mental health care in a secured setting not available in Wisconsin.

Attorney:

Brave and being thoughtful …

Narrator:

Judge Gaylord calmly presides over tense interactions, hearing from the child’s mother, also by phone.

Gaylord:

This is going to be slow when there’s a history of this kind of treatment, frankly, by you… and by others.

[girl’s mother starts speaking]

Gaylord:

No, ma’am. Ma’am, It’s my — It’s my turn to talk.

Mother:

But she has not had — She has not had that chance to deal with …

Narrator:

The process is often fraught. Gaylord concluded this hearing, encouraging the girl on the phone to keep up the hard work of dealing with her trauma.

Judge Shelley Gaylord:

Things that happened to you are not your fault. Things that you do are your responsibility to fix. Right?

Narrator:

The teenager we visited in Arkansas said the intensive treatment there helped her, but she was conflicted about sending other children like herself out of state.

Girl:

If it’s going to help, then go for it. But I would love to see every kid in Wisconsin just stay there, just stay at home. Yes.

Narrator:

Sending children out of state is a last resort. But even in the home community, the kinds of transitions children in foster care can experience layers trauma on top of trauma according to those who’ve lived it.

Tina Czappa:

Just the uncertainty of knowing where your next bed is gonna be, who’s going to be your family next, and who you can really trust, who’s being there and being real for you. It’s very confusing and unsettling for a child.

Narrator:

Foster youth advocates like Tina Czappa are giving back. Hopeful for a new generation, hopeful because of an emerging awareness of the impacts of trauma and new responses to it. She offers this advice to children who’ve experienced the trauma of abuse or neglect, of repeated placements, of being in the system.

Tina Czappa:

You didn’t choose it and it was someone else’s choice and control. And that doesn’t make you wrong, or damaged, or someone that can’t be loved. And that’s really an eye-opening important part in the healing of any trauma that someone goes through because that’s definitely a thought that occurs very frequently is, “What is wrong with me?”

[dog huffs, barks, jingles]

Alisha Fox:

Stop. What is wrong with you? Come on! Yeah, good girl.

Reyna Saldaña:

Trauma-informed care is about a culture change. It’s about shifting the way we understand behavior and how we respond to it. I think if people knew about trauma-informed care, I don’t think I would have gone through as much.

Narrator:

An understanding of trauma’s impact on physical and mental health first emerged more than 20-years ago. In response, trauma-informed care has emerged in the decades since.

Chuck Price:

How do we start, you know, asking every single time we’re working with families that question, the trauma-informed question of switching the lens from, you know, “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?”

Narrator:

Trauma-informed care expert Elizabeth Hudson says this so-called “switching the lens” results in a perspective shift allowing teachers or caregivers to recognize why a child might be acting out or shutting down.

Elizabeth Hudson:

What becomes hard is when the behaviors push people away or turn people off.

Narrator:

Tammy Fry says after her mother died and she was removed from her father’s care because of abuse, her anger would erupt.

Tammy Fry:

I got charged with battery and then I spent most of my years in detention.

Elizabeth Hudson:

One of the big shifts in perspective is being able to see the behavior as a communication.

Narrator:

Communication as the expression of trauma. But with trauma-informed care, the point is to not blame or shame people for their behavior.

Caregiver:

You want to fix my hair?

Child:

Yeah.

Tim Grove:

We know that one of the hallmark symptoms of kids trying to sort of work their way through that overwhelming stress for some of them is to stare blankly at the chalkboard.

Alisha Fox:

Yeah.

Narrator:

An experience familiar to Alisha Fox.

Alisha Fox:

But, there’s ways to deal with it now.

Tim Grove:

And the teacher’s approach is critical.

If I approach her and I say, “Hey!” [knocking] and maybe startle her further by banging on the table, I’m actually potentially going to make it worse.

If I’m more careful and informed about how I approach her, I might actually help her relax and settle down and make it better.

[energetic kids holler, laugh]

Elizabeth Hudson:

But what we know about many of these kids is they have had to adapt to the stress in their life by, in many ways, shutting down when it comes to relationships because relationships have been the hardship and they have caused the danger and the lack of safety.

Reyna Saldaña:

I built this wall where it was like, after a young age, I knew that it was only me.

[brushing sounds]

Narrator:

When Reyna Saldaña was removed from her home because of abuse she was placed in a succession of facilities. But when she was 12 years old, she says a riding mentor made a critical connection.

Reyna Saldaña:

I didn’t really have anybody until I met her. I went out there, originally, not because I wanted to ride horses, but because I got in trouble with the law and I had to do community service. She let me know that, like, there are things about me that she loved, that I could love, that I just had to understand myself more.

Narrator:

Trauma-informed care experts say safe and trusted human connections are the key to healing and behavior change. Connections like those Alisha Fox came to develop with her grandmother and aunt.

Grandmother:

She’s a keeper, aren’t you, Bella?

Elizabeth Hudson:

We know it’s the relational dance with other people that is going to build their neural capacity to have stronger relationships.

Alisha Fox:

Good dog!

Tim Grove:

One of the kind of insidious and lesser-known impacts of kids who experience trauma is often it’s their source of identity. Their families that are — that are hurting them. How do you make sense of that?

Alisha Fox:

I was just trying to survive until I got older and you become more knowledgeable about relationships and things like that. And then, I finally was like, “Well, this doesn’t seem right.”

Narrator:

The trauma-informed care model emphasizes physical, psychological, and emotional safety.

Tim Grove:

With enough grown men and women who help you, who provide safety, who provide regulation or relaxation, eventually, you can at least establish a competing truth. And then, you’ve at least got a fighting chance.

Narrator:

That fighting chance comes from developing resilience. Research shows the number one factor for children who develop resilience is having at least one stable and committed relationship with a caring adult.

Alisha Fox:

Once you make connections like that, you’re strong enough to tell your story and you deserve a better life than what you’re living right now.

Narrator:

Resilience also comes from learning how to self-regulate, especially when overcome by anger.

Reyna Saldaña:

As soon as I start to feel an emotion like that and then process it away from people and, like, collect myself, helps me be able to go back and then approach the situation at a different angle.

Narrator:

Caring adults can show children how to regain the calm within themselves.

One of the main things that we can do for kids and families in these situations is allow ourselves to be at peace and balanced during our interactions.

Tim Grove:

The idea that the possibility of another alternative exists is the beginning prospect of hope and we see those stories all the time.

Kids, families, adults, even now a growing number of communities who are feeling the effects of saying, “Huh? There’s a whole new truth. There’s a whole new possibility:

Maybe all humans don’t hurt. Maybe I can relax and take some relational risk. Maybe I can feel safe.”

That really is the essence of what the outcome of trauma-informed care is all about.

[children laugh joyfully]

Chuck Price:

It’s really about taking on that whole philosophy and really embedding that.

Narrator:

Child welfare agencies, courts, schools, and workplaces across Wisconsin are starting to take on the philosophy of trauma-informed care.

Erica Becker:

It first began with, right, the number one goal that we’re not going to place any children with a stranger.

Narrator:

Child Protective Services staff in Waupaca County describe how they now work,

Cristin Bauch:

I think of how many families would say, “Don’t take my kids away!” the first time I met them. I said, “Whoa, I don’t even know you!

[laughs uncomfortably] I don’t even know who your family is. That’s why I’m here today to figure out who you guys are, what you do.”

Alisha Haase:

So, we’re entering homes, not giving off judgment, really wanting to welcome them into a role or our services. Building that trust with them as far as just taking time, you know, figuring out what it is that they could use help with. You know, not shaming or blaming them. Obviously, I don’t think anybody wakes up in the morning and says, “I want to hurt my child.” And so, really identifying that we know that they love their kids and that they just need help in this situation and trying to find a way to partner with them.

Is the safety issue present in the home most of the time? Or, is this something that happened once because, you know, dad lost his cool? And now, how can we get it to support him in the home so that next time when this comes up, he’s not responding in that way?

Narrator:

Waupaca County’s child welfare agency can measure the success of its new model.

Chuck Price:

We’ve seen a pretty significant reduction in the amount of placements that we’re doing outside of the parental home. And so, when we’re talking about foster care, our foster care numbers have been down. My first whole thing with trauma-informed care was about how are we gonna treat the folks coming through the front door better than they’ve ever been served and with a whole different understanding of traumas and adversities that they’re bringing and not to further traumatize folks.

Narrator:

Human Services Director Price first learned of trauma-informed care when former first lady Tonette Walker was touring the state promoting her “Fostering Futures” platform.

Tonette Walker:

It’s talking about what happened to someone and really moving on from that point. Not staying there in dwelling on that, but really saying, “You know what? We know that you can — we can teach you resiliency, we can change the way that you act, that you can change your behavior,” and moving forward. And so, for us, it’s a philosophy change.

Narrator:

And given her position, Walker was able to get trauma-informed principles incorporated into seven state agencies.

Elizabeth Hudson:

I know that people across the country are calling us and they’re asking us how we’re doing this. We are getting attention internationally. We have a voice that is saying, “This is important.” And definitely, within our governmental structures, this is unheard of.

Tonette Walker:

We brought the three branches of government together. We had judges and legislatures together. Republicans, Democrats. We never even asked if we were Republican or Democrat. It doesn’t matter.

Narrator:

Waupaca County was able to save costs by not placing children in expensive treatment centers. The shift allowed for more staff and less turnover. It meant hiring in-home parenting aides to help families learn and heal. With that number one goal being to keep families together because experts acknowledge repeated out-of-home placements result in new traumas.

Carey Sorenson:

And I think that’s the hard thing about trauma I think a lot of people — I hear a lot of people say, you know, “Just get over it,” or “Just go through it,” or “Just get done with it.” That is not the way it is. Trauma sits with you.

Narrator:

Carey Sorensen cares for a boy Waupaca County placed with her after removing him from his own home. She’s a relative, so he’s not with his parents, but he’s also not with strangers in foster care.

Carey Sorensen:

It became very evident that they understand trauma, they understand how to help people with trauma, they understand how to come into a home and be respectful of every player in the situation. No judgment was ever felt.

[Wendell Waukau speaking Menominee]

Pōsōh mīp, good morning. How we doing? All right. Pōsōh mīp, Pōsōh mīp, good morning!

[in jovial voice]

Pōsōh! Hey, good morning! Hey, we got time for a shoe tie?

Narrator:

Every morning, the superintendent of the Menominee Indian School District greets grade school students at the front doors.

Wendell Waukau:

Why can’t our kids, before they even walk into the classroom, why can’t they be greeted by caring adults?

Social Worker:

Good morning, guys. Good morning!

Ryan Coffey:

Hello there, smiley. Good morning.

Narrator:

A social worker and trauma coach also man the bus arrivals.

Ryan Coffey:

We’re both out on buses at the end of the day, too. When the kids come out and we’re all, you know, “Have a good night, we’ll see you tomorrow,” just to remind them that we’ll be here tomorrow, and we welcome them back again.

Narrator:

The school works in many of what they call “positive touches” that happen before the students even open a book.

Margaret Snow:

Pon— waepenon. Pōsōh, waewaenen. Pōsōh mīp! Hello, early.

[Margaret laughs]

Narrator:

Identity that may have been stripped through the generations is reinforced.

Margaret Snow:

I teach Menominee language and culture. Pianon, come on! And I like to introduce myself in my native language.

I teach Menominee language and culture. Yeah, come on! And I like to introduce myself in my native language. Margaret Snow eneq āēs wīhseyan mōhkomānēweqnaesen. My English name is Margaret Snow.

Narrator:

Reinforced to help heal from historical trauma which traces back hundreds of years.

Wendell Waukau:

One term I heard from an elder was, you know, basically, what happened to us is we got an “ethnic cleansing.”

We were told we were no longer Menominees. And today, we addressed that by going back and honoring our ancestors who endured all of that — that pain and suffering that allowed us to be here today. Take the example of kids who were taken, removed from their homes and then placed in boarding schools. Well, essentially, what happened was you took away the parent’s right to parent.

They were learning their language, their culture, their identity and you took that away from them. This was passed on through generations.

Michelle Frechette:

When you live in this community and you work in this community, I think that we don’t realize how deep the trauma can be for some of our students.

Isaac Webster:

But when it comes down to it, our community is really broken.

Deziray Sanapaw:

Drinking and drugs and alcoholism, and, like, it repeats itself a lot and, like, it affects the kids growing up because you have to deal with it. The school helps us. You get in trouble, they won’t yell at you or tell you. They’ll question you and let you talk to them and they want to know how you feel.

Narrator:

Wendell Waukau went to these schools and later returned as superintendent.

Wendell Waukau:

I am from the Menominee Nation. Proud.

Narrator:

Ten years ago, Waukau set out to address factors like adverse childhood experiences that he believes result in his district having some of the lowest student achievement rankings in the state. He says tribal leaders embraced the concept of healing and resiliency in partnership with the State initiative. Waukau says, “It’s a community public health effort — not just 8 — 3 during the school day.

Class:

For four years.

Kate Mikle:

For four years. How long is four years?

Class:

Forty eight months.

Narrator:

But in the schools, the work is deliberate and encompassing, reaching from the high school.

Kate Mikle:

If they’re five minutes late or a half an hour late, it’s still, “Hi, I’m glad you’re here,” not “You’re late. Where were you?”

Narrator:

To the grade school.

Myrtle Mahkimetas:

Last week, we were doing our state testing and one came in, and out of the ordinary, he had his hood on. And he sat and I could tell there was something wrong. I knew from all the training that we had that we weren’t going to get any results from this test that we needed.

Pretty much all he needed was just some time to say, “It’s Okay. Whatever happened this morning, it’s done, it’s not here at school.”

Narrator:

In this fifth grade classroom, students arrive to calming music and dimmed lights.

Teacher:

Pōsōh mīp!

[bell rings]

Make sure you check in.

Narrator:

In time, they’re asked to check in. This means they register how they’re feeling that morning by marking on a computer whether they’re in the front seat of a car and ready to go or in the trunk, feeling bad and not ready to learn.

Teacher:

Okay, I can’t push this child so hard today. There’s something going on in his or her life that I need to be more understanding of what’s happening with them today.

Teacher:

Thank you. Miguel and Darren, would you guys please be sure to go check in so I know how you’re doing today?

Narrator:

In the younger grades, the children put a stick in a colored pot. Green for good, yellow for not so good, and red for feeling bad.

Teacher:

Hey, I saw that you were on yellow. What’s going on? What’s the matter? Come here.

Narrator:

The teacher immediately responds, asking about the student’s family. The child says she’s hungry and so, it becomes snack time.

Teacher:

Who would like to start and tell me what made them happy?

Narrator:

The classrooms have safe zones and calm down boxes and children can go to them at any time.

Ryan Coffey:

We’re finding out that kids from trauma, when they come into schools, they have walls up because they have trust issues sometimes and so we need to build those relationships first, before any learning can take place.

Narrator:

Ryan Coffey is the trauma coach on staff at the grade school. His office is always open for children who need more help understanding their feelings. It’s called the “Peace Room.” I talk about a time that I felt lonely, and then, they spin it, and they’ll talk about the time that they felt whatever. It’s part of the coping process. They need to know what it is inside and how or what the best strategy is to deal with those feelings. I mean, we want them to know that no feeling that they ever have is bad. Feelings are good, and they’re there for a reason.

Girl:

I go out to the Student Health Center every Wednesday to talk to somebody.

Narrator:

For students in all grades who need additional help, the health center is right on school district grounds, staffed by behavioral health professionals. The schools also provide dental care.

Wendell Waukau:

Our promise was that we would engage the community in a process that could build and could help heal. A lot of our social and health determinants that impact so many, so many things, education being one of them.

Narrator:

Waukau says the district has moved beyond trauma-informed to trauma-responsive and it’s working.

Waukau:

We have put resources into key grade levels, particularly ninth grade. Where now, instead of graduating 60% of our kids on time, were at 90%.

Narrator:

But slowing down, calming down, talking: Who can do all that and still teach?

Waukau:

People say, “Well, you won’t have enough time.” Well, yeah, but that’s all we have.

Teacher:

You guys get to play seven games today.

Children:

Yeah!

Narrator:

And now the Menominee Indian School District has brought its trauma-responsiveness into its preschools.

Wendell Waukau:

Well, we’re not done because we need to get into the pediatricians’ office. But, more importantly, if this is really going to work we’ve got to get this into the homes because those are where the teachers are.

Judge Mary Triggiano:

We understand so much more about trauma and its impact on our families and behavior of our families.

Narrator:

In the state’s largest city, trauma-informed care starts with baby’s first breath.

Judge M. Joseph Donald:

You say to yourself, “Well, there’s something else. We have to do something else.” There’s another way at getting at these root causes.

Narrator:

These Milwaukee County judges are getting at root causes and starting early. They preside over a healthy infant court, the first in Wisconsin.

Judge Mary Triggiano:

Babies are the largest population of those that are removed from parents in our system, both locally, statewide, and nationally, and mostly for neglect.

[children laughing]

Jonisha Neita:

I came to lose them at twenty … three. I was 23 when I lost my kids. I couldn’t believe that was me. I was my mother all over.

Narrator:

Jonisha Neita is a former drug user. She lost five children to child welfare authorities, including an infant who is now three. She was the first graduate of the Healthy Infant Court. Her children are back home with her, but by her telling, going through the court process to regain custody was not easy.

Jonisha Neita:

Even when I was referred there, it still wasn’t mentally hitting me. I’d used to always be the person sitting in the back with my hood up, and just sitting there, like, crying. Every time I talked to the judge, I just cried.

Narrator:

The court then assigned infant mental health specialist Katy Trottier to work alongside Jonisha.

Jonisha Neita:

Actually, it was the point of my life where I had to start trusting somebody, that reality of knowin’ that I have to start trusting. I had to start believing in something. And Katy was the person that walked through the door.

Judge M. Joseph Donald:

Because they’re like, “Well, wait a minute.”

Narrator:

The judges are equipped with expert training to learn about infant mental health and signs of toxic stress in babies.

Judge Mary Triggiano:

A child who might cry incessantly for hours and hours and a parent not being able to comfort them, or a child who you would think is going to cry when they’re hungry, but gets sort of this sullen, glassy look to them.

Narrator:

Jonisha’s babies showed such signs of stress and she didn’t know how to feed him without a struggle. She admits she didn’t have a good model in her own mother and there was trauma going back. My mom was a drug addict. She got married to an abusive guy, which was my step-dad. Still is my dad.

Katy Trottier:

It’s not just who that parent and who that child are. It goes back to how you were parented. So, what we find so often is there’s… There’s ghosts in the nursery. That’s what infant mental health is all about. There’s ghosts in the nurseries.

Judge Mary Triggiano:

When a mother who has been impacted by years and years of toxic stress, whether that mother was a child welfare child herself or was abused or neglected or sexually assaulted, they don’t create those procedural memories that we might have from watching our mothers.

[child jabbers happily]

So, we’re actually creating new procedural memories by helping them work with the infant mental health specialist to learn how to parent.

Jonisha Neita:

I say, like, a month into doing what I was doing with Katy, it was like he actually started looking at me in my eyes.

Judge M. Joseph Donald:

It’s amazing when you actually see the connection, when there is a strong and healthy bond between mother and child and father and child and then the child, when they are secure and healthy, also develop the ability to exercise some self-regulation.

Narrator:

This connection and newly-patterned parenting skills allow Jonisha to bring her children home.

Judge Mary Triggiano:

We knew that we could protect the brain development of those children so that they would have a better chance of not being pulled deeper into the system.

[children chatting and laughing]

Narrator:

Jonisha says after successfully learning how to parent all her children are doing well.

Jonisha Neita:

They’re happy. That’s all that matters that, yep, they’re happy.

Narrator:

Her bond with her once-fussy baby is clear.

[Neita plants a kiss]

Katy Trottier:

Oh, he is just lovely!

[happy laughter]

I love him. I love him.

Narrator:

And so, all across Wisconsin a growing culture change toward positive futures for generations to come.

[road traffic and water current]

Bonita Hahn:

Alisha came to live with me when she was 16. She was living with Michelle.

Narrator:

After being abused by her father for 10 years, Alisha Fox’s grandmother gained custody of her. Alisha’s Aunt Shelly lives in the same house. They say it took four years for Alisha to be able to communicate with them.

Bonita Hahn:

It was hard for us because Alisha couldn’t express herself so I — I remember one night when she was having some bad night terrors or PTSD was going on or flashbacks and she was curled up in her bed in the fetal position. And I — She just wouldn’t speak or anything. And that was when I first got her and I — I literally didn’t know what to do. So, I just pulled a chair from the kitchen and pulled it next to her bed and just sat there in case she would get up or need me or… I mean, so sometimes, it’s just a matter of being there, even if you don’t think you’re making a difference, just have to be there.

Alisha Fox:

I knew even in my darkest times that they were there. I’m not concerned about whether somebody is gonna hurt me or whether I’m not gonna have food on the table or whatever the grave situation might be.

Bonita Hahn:

Okay.

[laughter]

Alisha Fox:

I can go home. I go home to my dog and to my family. It’s a loving environment and that’s where people can strive. When they have connections, they strive and when they don’t… they don’t get their needs met — and my needs are met and times 10. So, that’s where… That’s where healing can begin. That’s where your recovery story can happen.

Tammy Fry:

So I’ve probably been in over ten foster homes, group homes:

three. I’ve been in the juvenile shelter home like three, four times, and then, the detention center, I was there probably a lot.

[ducks quacking]

Narrator:

After her mother died and she was removed from her home because her father abused her. Tammy Fry had gotten in enough trouble that the state recommended she be sent to the juvenile prison for girls. The judge in her case did not send her. Instead, she went to one last foster home. She is now aged out.

Tammy Fry:

When I get stressed out sometimes I just pray to my mom. I don’t know. Makes me feel better.

Narrator:

Tammy has advice for adults who work with children who have experienced trauma.

Tammy Fry:

Be mindful and respect what the kids have been through. And just kind of work with them and not give up on them. Give them chances. Work with them — not just throw ’em back out to be placed in another home.

[speaking “Motherese”]

What are you looking at? Yeah.

Narrator:

Tammy has started her own home and family.

[laughing, making kissy noises]

She recently had a baby, naming the girl after her late mother.

Tammy Fry:

My mom is part of her. I really do believe that. I want her to have the life that I never lived, that I never had. That’s… She’s my everything. I would do anything for her.

Reyna Saldaña:

Sometimes, when I’m really confused or I’m really stressed out. Just being around a horse is, like, really helpful to me because… they put me in check, I guess, with understanding myself.

Narrator:

Reyna Saldaña says she learned more about how to find calm, be able to pull herself back from violent outbursts after coming to understand her trauma — trauma resulting from abuse and then, repeated placements where she was physically restrained, including the juvenile prison for girls.

Reyna Saldaña:

Speaking about it sometimes is really raw for me because I haven’t even really worked through a lot of it, you know.

Narrator:

But with the help of caring adults, Reyna worked through enough of it that she graduated from high school and never entered the adult prison system.

Reyna Saldaña:

What?

Narrator:

She says when she was a child no one seemed to understand her behavior was the result of trauma. Today she understands she is resilient.

[Saldaña getting choked up]

Reyna Saldaña:

I don’t think giving up is really an option [sniffles] because I feel like I have a lot to say that other people may not have experienced. And I really hope that, like, [sniffles] if I keep going, and pushing through my things, I can help those other kids. Like, the other kids I roomed with in these facilities and the other kids I watched be restrained, when there was no need for it but I knew that, but the facility didn’t.

Awesome, good girl! I started doing speaking and being able to say my story. It took me a while to even decide to do that ’cause I was like, “No. “No, I don’t want people to know. I don’t even want to think about it.”

I am still today as an adult working through things that happened to me when I was 10.

[speaks to horse] We got this.

Judge Everett Mitchell:

These children — they want to make us happy; they want to be proud. But they just need somebody to take the time to slow it down, to make sure they get things they need. I though we gonna eat some fried fish together.

Narrator:

As for the 16-year-old in so much trouble who appeared in his courtroom…

Judge Everett Mitchell:

So much pain, so much pain, so much brokenness.

Narrator:

Judge Everett Mitchell just wishes someone, anyone had taken the time so much earlier to see the trauma and help set the boy and others like him on a better path.

Judge Everett Mitchell:

I really have embraced the idea like Frederick Douglass said, “It is far easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.”

Narrator:

For more information and resources, visit W-P-T dot org slash trauma.

Funding for Not Enough Apologies: Trauma Stories was provided by Focus Fund for Journalism and Friends of Wisconsin Public Television.

Series: Trauma-Informed Care in Wisconsin — Many Wisconsinites have experienced traumas in childhood, but their effects are not universal, nor are their burdens evenly distributed among the state’s different communities. Depending on the individual, trauma can have a lifelong impact, affecting behavior, relationships and physical, emotional and mental health. The burden of childhood trauma and the toll it takes on individual lives and public health is attracting more attention by health professionals, educators and caregivers. As a result, public and private organizations around the state are incorporating trauma-informed approaches into their daily work with children and adults. These approaches are part of efforts to transform Wisconsin’s human services and justice systems in the hope of providing better outcomes for traumatized individuals and communities.

Series: Trauma-Informed Care in Wisconsin — Many Wisconsinites have experienced traumas in childhood, but their effects are not universal, nor are their burdens evenly distributed among the state’s different communities. Depending on the individual, trauma can have a lifelong impact, affecting behavior, relationships and physical, emotional and mental health. The burden of childhood trauma and the toll it takes on individual lives and public health is attracting more attention by health professionals, educators and caregivers. As a result, public and private organizations around the state are incorporating trauma-informed approaches into their daily work with children and adults. These approaches are part of efforts to transform Wisconsin’s human services and justice systems in the hope of providing better outcomes for traumatized individuals and communities. Q&A: Not Enough Apologies: Trauma Stories — After addressing issues of gun violence in the 2016 documentary Too Many Candles, Wisconsin Public Television’s Frederica Freyberg wanted to tackle another issue that seemed too big to address in the same program.

Q&A: Not Enough Apologies: Trauma Stories — After addressing issues of gun violence in the 2016 documentary Too Many Candles, Wisconsin Public Television’s Frederica Freyberg wanted to tackle another issue that seemed too big to address in the same program.

Wisconsin Children’s Mental Health Collective Impact is an innovative and structured approach to systems change. This page includes the action team’s continuum of trauma-informed care framework. The workgroup brings together a wide variety of stakeholders who use data to identify root causes of a problem and then design strategies to bring increased well-being to Wisconsin’s children and families.

Wisconsin Children’s Mental Health Collective Impact is an innovative and structured approach to systems change. This page includes the action team’s continuum of trauma-informed care framework. The workgroup brings together a wide variety of stakeholders who use data to identify root causes of a problem and then design strategies to bring increased well-being to Wisconsin’s children and families. The Boys and Girls Club of the Fox Valley integrates trauma-informed care into their service model. In February of 2016, they co-authored, along with United Way Fox Cities and twelve other agencies the Trauma-Informed Roadmap. This includes a vision of the Fox Cities in which they articulate: “Everyone in our community is treated with compassion and respect, which allows them to thrive regardless of circumstances.”

The Boys and Girls Club of the Fox Valley integrates trauma-informed care into their service model. In February of 2016, they co-authored, along with United Way Fox Cities and twelve other agencies the Trauma-Informed Roadmap. This includes a vision of the Fox Cities in which they articulate: “Everyone in our community is treated with compassion and respect, which allows them to thrive regardless of circumstances.” A 2011 study on quality of life in Wisconsin’s Fox Cities — called the 2011 Local Indicators For Excellence (LIFE) study — indicated children and teens in the region needed better access to mental health care. In response, the three major health systems in the community — Affinity Health System, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin and ThedaCare — partnered to form Catalpa Health. Since its founding, Catalpa has added new providers and services, all in an effort to meet the growing demand for access to mental health care in the community.

A 2011 study on quality of life in Wisconsin’s Fox Cities — called the 2011 Local Indicators For Excellence (LIFE) study — indicated children and teens in the region needed better access to mental health care. In response, the three major health systems in the community — Affinity Health System, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin and ThedaCare — partnered to form Catalpa Health. Since its founding, Catalpa has added new providers and services, all in an effort to meet the growing demand for access to mental health care in the community. — Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin works to address and help heal trauma, avoid re-traumatization and foster resilience. Explore evidence-based information and resources for parents and caregivers, health care providers, educators and potential foster parents.

— Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin works to address and help heal trauma, avoid re-traumatization and foster resilience. Explore evidence-based information and resources for parents and caregivers, health care providers, educators and potential foster parents. “What happened to you?” In 2015 the Menominee Nation was awarded the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Culture of Health Prize for its groundbreaking work using a trauma-informed care model to provide social and behavioral health services to the community, including in the Menominee Indian School District. Menominee Nation doctors and teachers begin with a central question, “What’s happened to you?” as opposed to “What’s wrong with you?” Learn more about this work and their award here.

“What happened to you?” In 2015 the Menominee Nation was awarded the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Culture of Health Prize for its groundbreaking work using a trauma-informed care model to provide social and behavioral health services to the community, including in the Menominee Indian School District. Menominee Nation doctors and teachers begin with a central question, “What’s happened to you?” as opposed to “What’s wrong with you?” Learn more about this work and their award here. is the Menominee Tribe’s singular, innovative and culturally-responsive adaptation of the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) framework for trauma-informed care. It weaves cultural practices and values of the Menominee into every aspect of the framework and stresses that traditional Menominee values of interconnectedness precede and inform the ACES approach that is now a mainstay of trauma-informed care.

is the Menominee Tribe’s singular, innovative and culturally-responsive adaptation of the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) framework for trauma-informed care. It weaves cultural practices and values of the Menominee into every aspect of the framework and stresses that traditional Menominee values of interconnectedness precede and inform the ACES approach that is now a mainstay of trauma-informed care. Peace4Tarpon is a community-wide trauma-informed care initiative in Tarpon Springs, Florida that serves as a national model for scaling up the geography and commitment of service initiatives. The organization works with the City of Tarpon Springs and has been instrumental in the city’s designation as an official Trauma-Informed and Resilient Community.

Peace4Tarpon is a community-wide trauma-informed care initiative in Tarpon Springs, Florida that serves as a national model for scaling up the geography and commitment of service initiatives. The organization works with the City of Tarpon Springs and has been instrumental in the city’s designation as an official Trauma-Informed and Resilient Community.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us