October is American Archives Month, a national invitation from the Society of American Archivists to highlight the importance of archives, how we share access to our collective record and the essential work of archivists and librarians.

To mark the occasion, we sat down with PBS Wisconsin’s in-house media archivist Ann Wilkens for an extended conversation about how she — in close collaboration with the station’s skilled engineering staff — safeguards our 70+ year legacy. We also discussed a recent major gift that makes it possible to digitize and share some of our earliest children’s educational programs on 16mm film, part of the Wisconsin School of the Air series from the earliest days of WHA Radio and TV.

Sigrid Peterson: Hi Ann! Tell our audience who you are and how long you’ve been with PBS Wisconsin.

Ann Wilkens: Hi! I’m our media archivist. In a nutshell, I ensure that every broadcast and digital program we’ve produced since our first broadcast as WHA-TV in May 1954 is preserved and remains accessible for future generations. I’ve been here 21 years! PBS Wisconsin was ahead of its time in recognizing the importance of archival work, becoming one of the first stations in the country to establish a full-time position for it in 2004. So, I’ve had the honor of being the station’s very first archivist.

Q: For those who may not know, what does a media archivist at a public broadcasting station do — and what might surprise people about the day-to-day work?

Wilkens: It’s very much a collaborative effort between the archives, engineering and production teams. I coordinate the transfer of program tapes to engineering for digitization, and once those files are ready, I enrich them with detailed metadata in our asset management system. Metadata is basically information about the media itself — things like program titles, dates, people featured, topics or technical notes — that makes the content searchable and useful later on.

We’re lucky to have the necessary playback equipment for all our legacy media formats, and the skilled staff who know how to operate and maintain it. When we say “legacy formats,” we’re talking about older technologies the station used to record video and audio before everything went digital — things like 16mm film, VHS, U-matic or Betacam tapes. These formats often require specialized machines to play that aren’t manufactured anymore.

I still find the work super cool, but some may not see my day to day as all that glamorous. My work is very hands-on: hauling dusty boxes, retrieving tapes from offsite storage, prepping film to send to vendors and sometimes even “baking” analog tapes. Yes, baking! Older tape formats absorb moisture, which breaks down the binder and causes the magnetic coating to shed, making the tape unplayable. A low-heat baking process removes that moisture and temporarily restores the tape so it can be digitized. It’s technical, gritty work at times — but I love it and it’s all in service of preserving our history.

A 1950s-era television control room shows the analog technology that powered early educational broadcasts at WHA-TV, now PBS Wisconsin. The equipment includes cathode-ray tube monitors, a reel-to-reel videotape recorder and control panels lined with knobs and switches, illustrating the hands-on engineering behind early public television production.(Source: University of Wisconsin-Madison Digital Collections)

Q: How does your work support the mission of PBS Wisconsin?

Wilkens: Our archived content is a vital historical record of public broadcasting’s legacy at the local level — preserving programming that reflects Wisconsin’s cultures, voices and experiences across time. By digitizing analog materials, we not only safeguard them but we open up the door to innovation — making it possible to integrate legacy content into new programming, modern platforms and interactive experiences. We’re committed to ensuring long-term access to our archives so future generations can continue to learn from and be inspired by our past.

Q: How long has PBS Wisconsin had a media archiving program?

Wilkens: We’ve always had some form of an archiving program — from preserving early film footage like news reels and educational programs to managing today’s born-digital content. As technology has evolved, so have our preservation methods. In the early days, we reformatted analog materials to other analog formats for safekeeping. For example, in the 1990s, we had a large collection of two-inch videotapes — a format widely used from the 1960s until the 1980s. As playback equipment became obsolete, we migrated that content to BetacamSP, which was the preservation standard at the time. Today, we have the infrastructure and expertise to digitize content into a variety of digital file formats, ensuring long-term accessibility and compatibility with modern systems.

Q: Roughly how large is the collection?

Wilkens: Our physical media collection includes approximately 45,000 items, spanning a wide range of broadcast formats such as one-inch, ¾-inch, BetacamSP, DVCPro, DVCam, D3 and HDCam tapes, as well as 16mm film, DAT tapes and ¼-inch audiotape. In addition to moving image materials, we also care for photographs, slides, design elements and photo negatives — many dating from the 1950s through the 1990s.

Paper-based collections of our archives are housed at both the Wisconsin Historical Society and the University of Wisconsin Archives. On the digital side, our collections total around two petabytes of data. The archive’s origins trace back to our very first broadcast in 1954, which featured Gov. Walter Kohler’s dedication of the station.

Q: What are some of the earliest formats in the archive, and how do you handle preserving them?

Wilkens: Our earliest materials are 16mm kinescope films—recordings made by pointing a film camera at a television monitor to capture live broadcasts. Since we don’t have a film scanner in-house, we work with a trusted vendor to migrate these films to digital formats. Another legacy format we work with is one-inch videotape, which despite its age, often plays back reliably. We’re fortunate to have functioning playback equipment for all our tape formats, allowing us to handle most transfers internally. We create digital files at the highest quality appropriate to the resolution of the original media.

Unlike audio, paper or photographic preservation, there are no universally agreed-upon standards for moving image preservation. The files we generate can be massive – while a typical home DVD might hold 4GB for a two-hour program, archival preservation files can range from 30GB to 90GB per program. When you’re digitizing thousands of programs, that storage adds up quickly.

Q: How much of the collection has been digitized so far?

Wilkens: So far, we’ve successfully digitized all of our series, standalone specials, documentaries and news programming. Currently, we’re focusing on field footage — material that’s historically significant, one-of-a-kind and highly reusable in future productions. We’re also working on digitizing programs and news film originally captured on 16mm which require very careful handling due to their age and fragility.

Q: Once something is digitized, how is it made accessible to producers, educators or the public?

Wilkens: Much of our digitized content is available through our website — but we’re digitizing faster than we can publish. So, if you’re looking for a specific program or have questions about early content, don’t hesitate to reach out. Behind the scenes, we use an internal digital asset management system that’s fully searchable and allows us to retrieve media quickly. If it’s been digitized, we can likely make it accessible for viewing (depending on copyright) even if it’s not online yet.

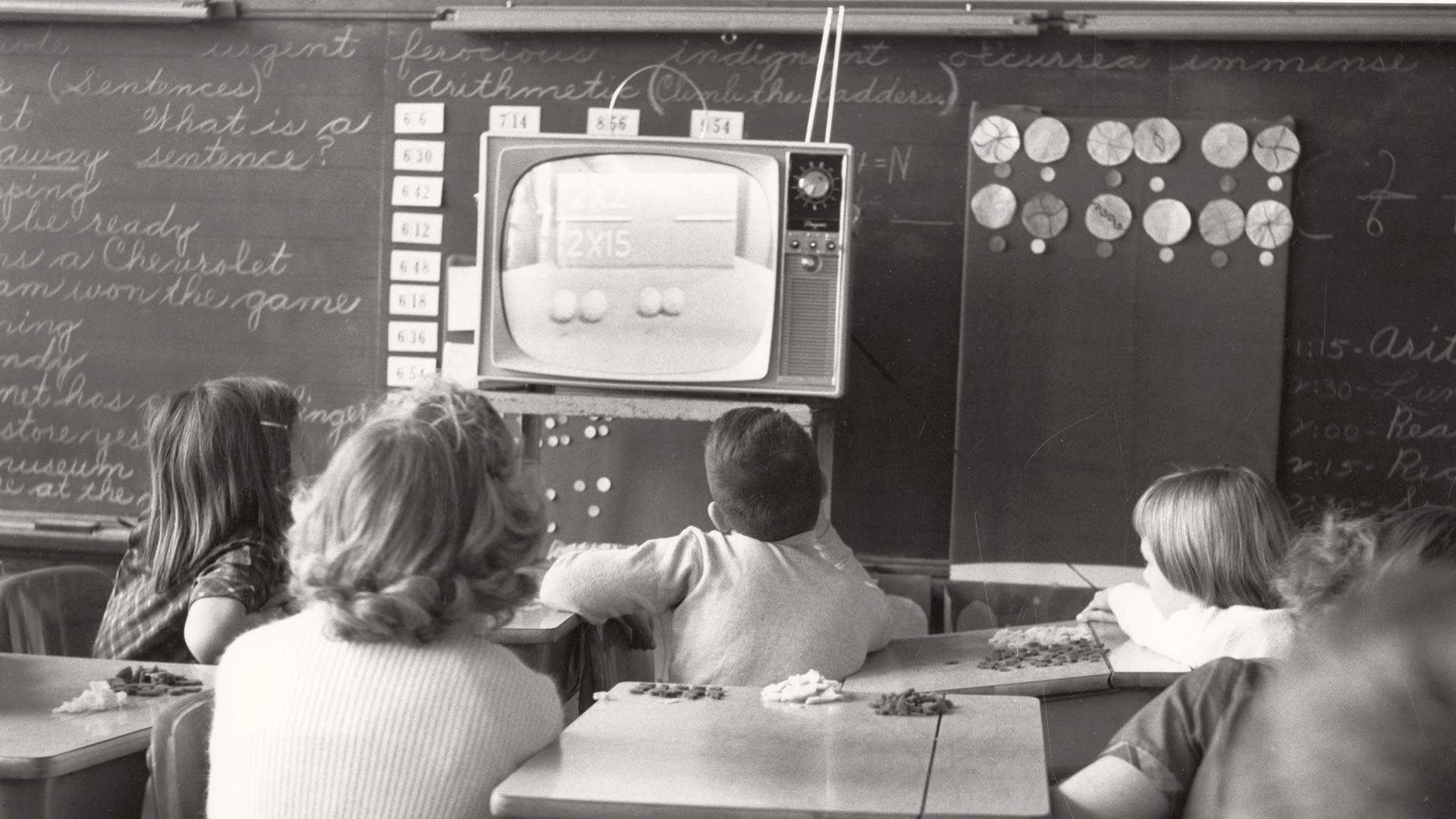

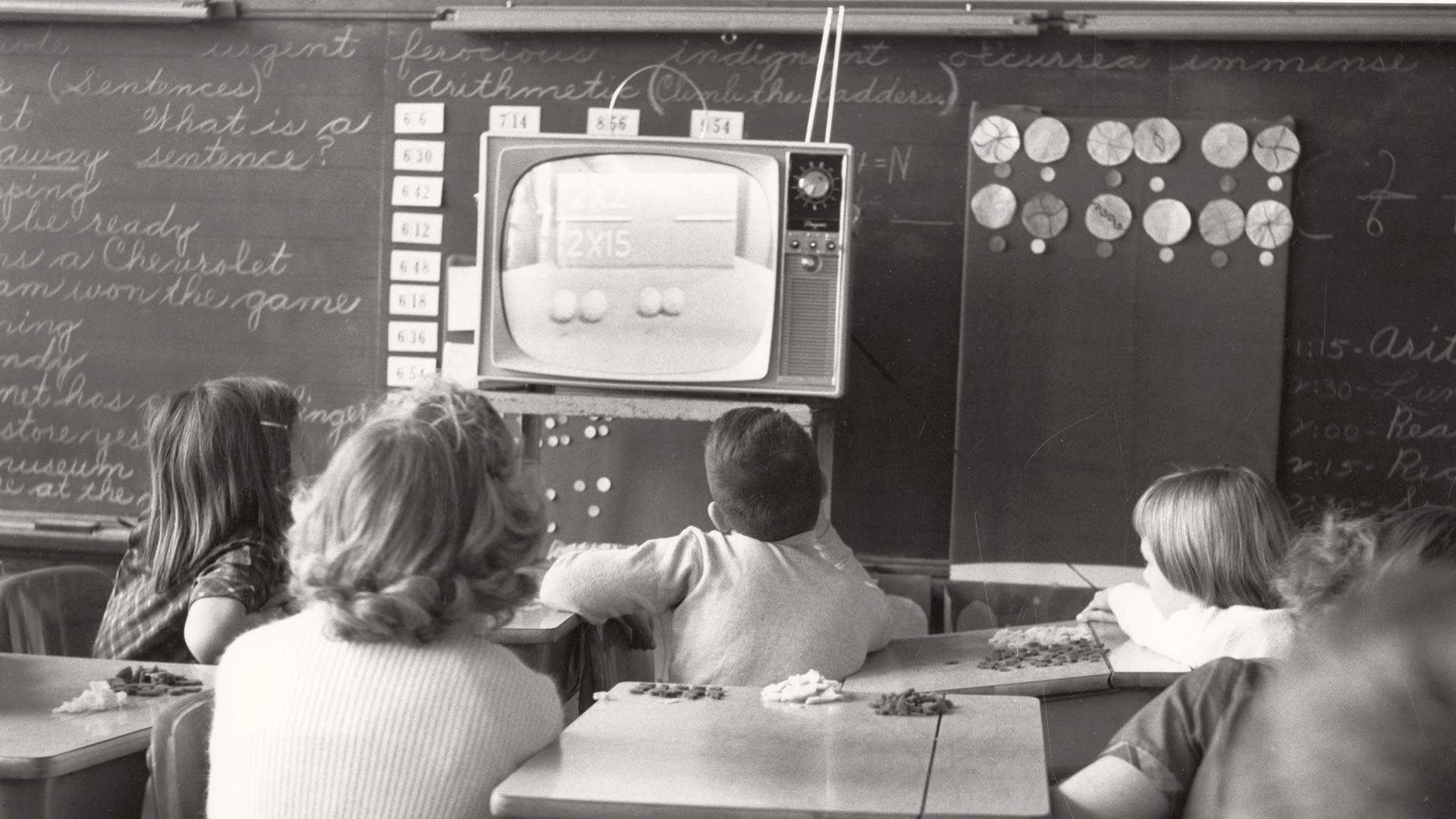

School children viewing an episode of School of the Air on WHA-TV. (Source: University of Wisconsin-Madison Digital Collections)

Q: Can you tell us about the recently funded Wisconsin School of the Air digitization project?

Wilkens: Yes. Thanks to a generous donor, our station received a $100,000 gift spread over four years to help preserve our aging film and video collections — some of which date back more than 70 years! We’ve prioritized our early children’s educational programs, and we’re now in the second year of this important work.

In year one, we successfully digitized 33 films. This year, we’re aiming to double that number. Alongside the preservation efforts, we’ve launched a newly renovated and vibrant archive website to showcase these digitized treasures. I’m thrilled to continue adding more content for everyone to explore.

Preserving these materials is a meticulous and time-intensive process. The whole collection is on 16mm film, which is deteriorating rapidly. While we can slow the decay, we can’t stop or reverse it — making timely preservation absolutely critical.

Each reel, often stored on metal spools, must be carefully wound onto cores. We add leader to both the head and tail of the film, then inspect it thoroughly to ensure it’s safe to run through a film scanner. It’s delicate work, but essential to saving these irreplaceable pieces of media history before they’re lost forever.

Q: Have you discovered anything unexpected or particularly meaningful in the School of the Air recordings?

Wilkens:: For me, this work has been a powerful reminder of PBS Wisconsin’s longstanding commitment to education and accessibility. It’s inspiring to see how creatively the station has collaborated with experts over the years to produce meaningful, engaging content, delivered free to educators, classrooms, children and the public.

Q: What are your goals for the archive in the next few years?

Wilkens: I want to make even more of our digitized content available and accessible online. I want to share the incredible documentaries we’ve produced, the groundbreaking news and educational programs we’ve created, and the delightfully quirky episodes that haven’t been seen in decades. I’m excited to bring them back into the public eye.

And I want to continue our work to digitize the earliest film collections which are some of the oldest and least accessible materials in our archive. This preservation work is urgent and essential.

Looking forward, I want to learn how to best preserve online games and interactive websites like Powwow Bound: A Menominee Homecoming and Wisconsin Lighthouses.

Passport

Passport

What do you think?

I would love to get your thoughts, suggestions, and questions in the comments below. Thanks for sharing!

Sigrid Peterson