The hidden secrets of domestic violence in Native communities

Domestic violence often goes unreported and the issue is not widely discussed in many Indigenous communities, but advocacy groups seeking to end abuse by partners and the traumas that follow are offering support and helping break this silence.

ICT News

October 2, 2025

Domestic violence research found that more than 80% of Native American women have experienced violence in their lifetime and more than 55% have experienced physical violence by an intimate partner. (Credit: Photo illustration by Mary Annette Pember / ICT)

Warning: This story contains disturbing details about domestic violence. If you are in an abusive relationship, you may seek help from law enforcement or advocacy groups listed below, or you can call the National Domestic Violence Helpline at 1-800-799-7233 or the Stronghearts Native Helpline at 844-762-8483.

MENOMINEE RESERVATION, Wisconsin —The police who arrived at the scene that fall afternoon were long-time veterans, one with more than 20 years on the job. They were still shaken by what they found.

A woman was lying unresponsive on a bedroom floor, so bloodied she appeared to have been stabbed or slashed. Instead, they learned, she’d been beaten nearly to death by her partner.

“They’d seen a thing or two,” Josh Lawe, a citizen of the Menominee Tribe and a detective with the Menominee Tribal Police, told ICT. “But the shock and awe of that scene, all the blood, was traumatic for us.”

The woman, from another tribal nation and identified only as O.W. in court documents, survived the attack and eventually left the area. The case served as a wake-up call to the Menominee community, where domestic violence — as in many communities, Native and otherwise — often go unreported.

The numbers are still staggering. A national report from the National Institute of Justice found that more than 80% of Indigenous women have experienced violence in their lifetime and that more than 55% have experienced physical violence by an intimate partner.

Nonetheless, it’s not an issue that is widely discussed. People mind their own business here on reservation lands, a collection of villages spread over 239,000 acres.

“People in the community don’t talk about their boarding school experiences, domestic violence or other fallout from trauma,” said Rachel Fernandez, founder of Woodland Women, a Menominee grassroots advocacy organization that works to end violence against Native women. Fernandez is a citizen of the Menominee Nation.

As the shocking details of the Sept. 20, 2024 attack emerged on social media, however, people began to take action, organizing activities to offer support and helping break a silence that fuels more pain and suffering.

While researchers say that unresolved generational trauma may push Native families and communities to keep dysfunction hidden, it also gives communities the power to protect and heal through culture and support.

“Unfortunately, our community has grown accustomed to crimes of domestic violence.” Lawe said. “It’s tough to shock people anymore. … I think this took a toll not only on the family but on the community as a whole.”

The one-year anniversary of the attack comes on the cusp of Domestic Violence Awareness Month approved by Congress for October.

Brutal attack

Much of the rage-fueled attack was captured on security cameras installed in the rental house by the homeowner.

Alerted by the home security system, the property owner viewed the live camera’s footage and contacted police. One camera showed the approach to an exterior door and another, mounted in the kitchen, provided an overview of several interior doorways.

The videos showed Nee Gee Cloud, 32, a Menominee citizen who had been in a relationship with O.W., kick open the door and search the house for the woman, who is shown hiding in a closet in the bedroom, according to a sworn statement filed in federal court by FBI agent Michael Meyer.

A few minutes after entering the home, Cloud can be seen leaving the bedroom and walking to the kitchen sink with blood on his hands. O.W. is visible in the bedroom, lying motionless, face down. Repeated assaults continue for nearly 30 minutes.

“Cloud washes his hands and face then returns to the bedroom where he stomps on O.W.’s upper torso and head area,” the agent stated, describing the video. “He returns to the kitchen, opens the refrigerator, grabs a drink and puts it on the table. Cloud returns to the bedroom where O.W. is still visible, motionless on the floor.”

The video stopped at that point, but the next video shows Cloud returning again to the kitchen, where he pours himself something to drink, and then returns to the bedroom. When he comes back out, blood is visible on his hands. He then returns repeatedly to the bedroom, grabbing the woman by her hair, kicking her head and midsection, slamming her head into the floor and returning to the kitchen periodically to wash his arms and face.

“During this time, someone can be heard yelling from the outside for Cloud to open the door,” the agent stated. “He closes the bedroom door and walks outside the residence with blood still visible on his arms. Cloud engages with several persons who have arrived at the residence asking if O.W. was alive. Cloud responds that she is alive. Shortly afterward, Cloud can be seen running toward the entry door as Menominee police pursue him. Officers deploy a taser on Cloud, restrain him and take him into custody.”

Lawe and other responding officers searched for a weapon, convinced the woman had been stabbed or cut. But Cloud used only his fists and feet in the attack, which left blood throughout the house.

An undated photo shows a greeting on a hillside on the Menominee Nation’s reservation in northeast Wisconsin. (Credit: Mary Annette Pember / ICT)

O.W. was transported by helicopter to a trauma center in the city of Wausau. She remained in an intensive care unit for nearly two weeks and was hospitalized for about a month. She sustained fractured orbital bones in her face and soft tissue injuries to her throat that required intubation in order to keep her airway from closing, according to a press release issued in August 2025 by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Wisconsin.

Cloud was convicted Aug. 6 by a federal jury in Green Bay, Wisconsin, of burglary and assault with intent to commit murder. He faces a maximum of 10 years in prison for the burglary count and a maximum of 20 years on the assault charge. He is set for sentencing in November.

“If police and emergency personnel hadn’t responded immediately, I’m confident O.W. would have passed away,” Lawe said.

Contacted indirectly by ICT, O.W. declined to be interviewed about the assault. Cloud also declined an interview via email from his legal counsel.

Emerging from the shadows

Congress declared October as National Domestic Violence Awareness month in 1989, recognizing that domestic violence is the single largest cause of injury to women in the U.S., affecting as many as four million women.

The passage of the law was among the first public clarion calls to recognize the pervasive, often-ignored destruction caused by domestic violence. Since then, lawmakers have passed several laws and legislation targeting violence against women, including the Violence Against Women Act in 1994, addressing the courts, policing, data collection, victims services and research into underlying causes.

Detailed, accurate data assessing the impact on Native American communities, however, is lacking.

The often-cited National Institute of Justice research report released in 2016 found that Native women and girls experience the highest rates of domestic violence in the U.S., and the report has been lauded for researcher’s efforts to oversample Native respondents.

But like other mainstream research efforts, it relied, at least in part, on data gathered from federal and local law enforcement, focusing primarily on perpetrators arrested and charged with domestic violence. The report ultimately concluded that 90% of the cases involve non-Native perpetrators, without taking into account how law enforcement and courts would identify whether a suspect is Indigenous.

And although reporting has improved, statistics from tribal courts and law enforcement are often omitted from national reports, which sometimes provide conflicting information. The Bureau of Justice Statistics, for instance, reports that domestic violence was the most common violent offense for which inmates were held in Indian Country jails from 2013 to 2023.

“There’s a lot [of domestic violence] that goes unreported, especially on our reservation,” noted Lawe.

Fernandez agrees, and estimates that 70% of incidents of domestic violence go unreported on the Menominee reservation. The Menominee Tribal Police did not respond to ICT’s request for data about domestic violence.

Nationally, researchers with the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that only about 45% of Native victims of violence report the crimes to police. Reasons for the reluctance include fear of reprisal by perpetrators and their families in their communities, lack of trust in police and courts, and the potential threat of losing home and children. Indeed, domestic violence has been found to be the leading cause of homelessness among Native people, according to the Pro Bono Institute.

“Sometimes people are so dependent on another person that they’re willing to just deal with it because they have nothing else, no support system,” Lawe said.

According to the National Congress of American Indians, there are very few reporting mechanisms for measuring violence against Native Americans. Barriers include high rates of underreporting by members of the community, jurisdictional issues, and lack of data-sharing between intergovernmental agencies and tribal governments. The Tribal Law and Order Act mandates the Bureau of Justice to establish a tribal data collection system that allows tribes and other law enforcement agencies to share crime data. The system is still in the works.

The Department of Justice has reported that tribal courts and law enforcement say that lack of funding, resources, inadequate infrastructure and understaffing are barriers to collecting and sharing data. In its 2024 report to Congress, the Bureau of Indian Affairs said that public safety and justice is funded at less than 13% of total need, and that an additional 25,655 personnel are required to adequately serve Indian Country.

Although the 2005 reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act included a requirement for the Justice Department to conduct a national baseline study to examine violence against Native women, the study has not yet been completed. The Justice Department reported lack of funding as a primary deterrent.

Tribal concerns regarding sovereignty of crime data sent to other agencies is also an issue, with questions about how the information may be used. Additionally, sharing information with federal crime databases such as the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program is discretionary, not only for tribes but for other local and state jurisdictions.

Historical trauma

Intergenerational violence, including domestic violence, is a response to unresolved historical trauma among Native people, according to researchers and advocates. Poverty, governmental oppression, racism, under-education and erosion of cultural and traditional life ways are all expressions of historical trauma.

Fernandez agrees.

“A lot of that violence that happened at boarding schools to our grandparents and great-grandparents was passed down because they were taught not to talk about it,” she said.

Denise Lajimodiere, a retired professor from the North Dakota State School of Education, notes that unresolved grief has not been expressed, acknowledged or resolved.

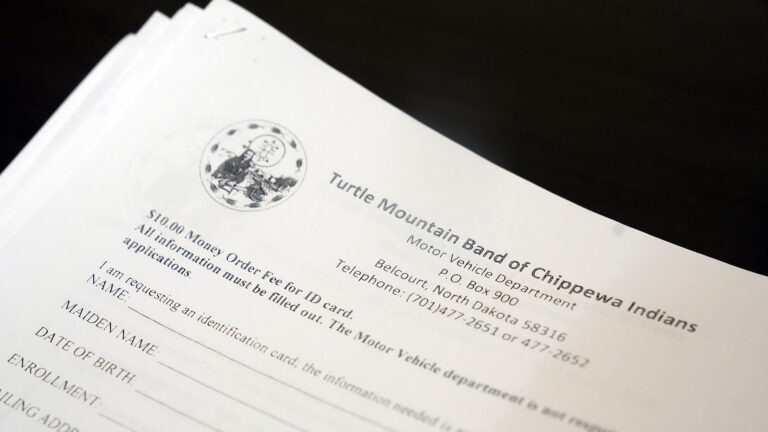

“It is disenfranchised grief that hasn’t been publicly mourned,” wrote Lajimodiere, Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, in a post for the PBS Native America blog.

There are few safe places where survivors of boarding schools or domestic violence can express their grief, she said.

“An elder asked me,” she said, “‘Where and when do we tell our family that we have been sexually molested? At Thanksgiving dinner?'”

Indeed, violence and childhood sexual abuse is commonly associated with becoming a perpetrator of domestic violence later in life. Perpetrators often repeat violent acts with new partners. Abusers learn violent behavior from family and community. They see violence and are victims of violence. Drug and alcohol abuse greatly increases the incidence of the crime, research shows.

And worse, childhood sexual abuse can plant the seeds of internalized rage linked to a common crime common among batterers – non-fatal strangulation. Cathie Anderson, a journalist with the Sacramento Bee, explored the powerful link between non-fatal strangulation and murder in cases of domestic violence.

In her reporting, Anderson found that women who are strangled are eight times more likely to subsequently be killed by their abusers. “If a battered woman is strangled even once by her partner, research has shown that she is 750% more likely to be murdered by him,” Casey Gwinn, a former San Diego prosecutor, is quoted as saying.

The correlation between non-fatal strangulation and murder is so compelling that most states and at least 31 tribes now prosecute the crime as a felony, seeing it as a red flag for escalating violence.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the felony conviction of assault by strangulation of a Native defendant in Indian Country in 2016. The judge explained that Congress added the offense of assault by strangulation to the federal assault statute in 2013 and noted that nearly half of domestic violence victims report being choked.

As a survivor testified before the U.S. Sentencing Commission in 2013 regarding strangulation as assault, “The neck is so easy to grab, so vulnerable, so vital to all life, connecting breathing and heart to mind. The viciousness and harm of this terrorist act is far different than mere broken bones or physical injury. … nothing else comes close to strangulation and suffocation in sheer terror.”

In an effort to uncover the roots of overpowering rage that drives men who strangle, Gwinn, who now works with survivors of domestic violence and offers a camp for minors who survived sexual or physical violence, found that those most filled with rage are most likely to have experienced sexual abuse. Strangulation is the ultimate expression of control, according to Gwinn.

“Many domestic violence offenders and rapists do not strangle their partners to kill them; they strangle them to let them know they can kill them-any time they wish,” Gwinn told the Sacramento Bee.

Warning signs

Cloud has a history of strangulation and domestic violence, with arrests and convictions scattered across other jurisdictions throughout the state of Wisconsin. There is no information indicating that Cloud has a history of childhood sexual abuse.

In researching Cloud’s criminal history, ICT found that in 2012 at age 19, he was charged with multiple felony and misdemeanor counts of domestic violence and two felony counts for strangulation. The charges were all reduced to misdemeanors with a recommendation that he enroll in anger management counseling. There is no indication if Cloud enrolled in counseling. Over the following years, Cloud was charged with additional counts of domestic violence and described as a “repeater.”

Anger management programs are not considered to be the best option for batterers, since they don’t address issues of power and control within relationships, according to the National Domestic Violence Hotline. Rather, Batterer Intervention and Prevention Programs, known as BIPPS, are considered more effective since they focus on accountability and victim safety.

The healing power of culture

Researchers are now finding that traditional Native values, belief systems and life ways can help address domestic violence.

“Violence against women is not a Native tradition,” according to a booklet of the same name created by the Sacred National Resource Center to End Violence Against Women. The booklet is available on the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center website.

“Our history of oppression laid the foundation for violence against Native women,” the booklet states. “The reality is that contemporary Native male attitudes about women and relationships have been distorted and the violent behavior of Native men towards Native women is tearing apart Native families.”

Joseph Gone, professor of anthropology and global health and social medicine at Harvard University, agrees. Gone, a citizen of the Aaniih Nation that is part of the Fort Belknap Indian Community, told a reporter with the American Psychological Association that he believes Indigenous spiritual practices can help Native people heal from generations of historical trauma.

Effective recovery and mental health programming for many Native peoples prioritizes socialization into Indigenous ceremonial practice, robust cultural identification and supportive community relationships.

Wica Agli, which means Bringing Back Men, on the lands of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe in South Dakota, uses traditional Lakota teachings in their services, which include Batterer Intervention and Prevention Programs.

The organization uses the Duluth Model in its Men’s Re-Education program. The Duluth Model, developed in the 1980s, places accountability for abuse on offenders. Wica Agli offers youth and cultural camps that focus on team building and traditional values of manhood that include partnering with horses.

Wica Agli is a modern version of the traditional Lakota men’s societies. Before European contact, it was in the men’s societies where men and boys were taught their roles in the community by elder men. They learned how to treat and support women while functioning as leaders and providers. Wica Agli helps men reconnect with Lakota teachings about healthy masculinity and instill a sense of accountability and civility to their families and community.

“We are holding perpetrators accountable and working to combat the hush-hush nature of domestic violence here on the reservation,” said Greg Grey Cloud, co-founder of Wica Agli in a previous interview with ICT. Grey Cloud is a citizen of the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe.

Looking ahead

The Menominee Tribe has a tribal-specific response to domestic violence.

The tribe operates a shelter for victims, and their law-and-order codes include a requirement that perpetrators convicted of domestic violence submit to a domestic violence abuser assessment and utilize treatment certified by the Wisconsin Batterers Treatment Provider Association.

The tribe had their own tribal BIPP, but the grant funding for the service expired. The tribe now refers perpetrators to other providers in the state. Tribal officials did not respond to requests for comment from ICT.

“They did a lot of great work for the people,” Fernandez said. “Hopefully, they’ll find a way to bring it back.”

She credits social media for calling attention to Cloud’s attack on O.W. and with building community resolve to take action. She and others are now holding classes in beading, regalia and ribbon-skirt making as a way to draw community members together.

“People said, ‘OK, we have to do something,'” Fernandez said.

Before the pandemic, Woodland Women helped organize many of the gatherings. The classes, she says, are for everybody but include a focus on healthy activities for the community.

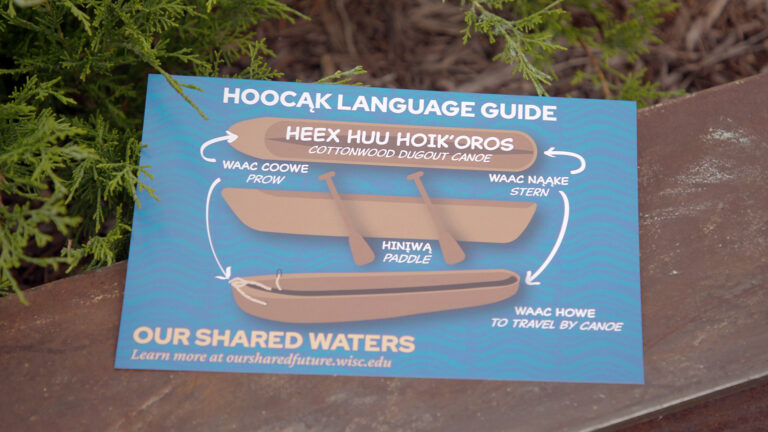

“Having the emotional support that emerges within the classes is so healing for people; they are safe places,” she said. “And the emphasis on culture is like real medicine for us.”

How to get help

Here is an incomplete list of organizations that focus on addressing domestic violence:

- National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center

- Stronghearts Native Helpline

- National Domestic Violence Helpline

- Tribal Court Clearinghouse domestic violence resources

- California Consortium for Urban Indian Health domestic violence resources

- The Coalition to Stop Violence Against Native Women

- Urban Indian Health Institute

- National Resource Center on Domestic Violence

- Domestic Violence Awareness Project

![]()

Passport

Passport

Follow Us