The Bolz Young Artist Competition is a highly-regarded statewide competition in which Wisconsin high school musicians compete for scholarships and the exciting opportunity to perform as soloists with the Madison Symphony Orchestra (MSO).

Watch the final round of the competition live on PBS Wisconsin and online at pbswisconsin.org at 7 p.m. Wednesday, March 6 in Wisconsin Young Artists Compete: The Final Forte. The full audio program will also air live on Wisconsin Public Radio’s NPR News & Music Network.

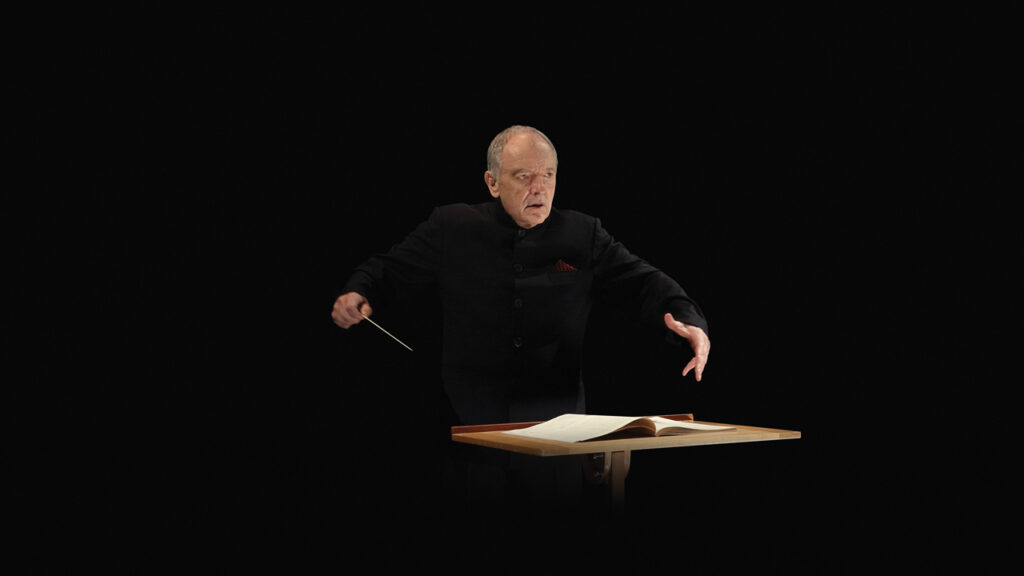

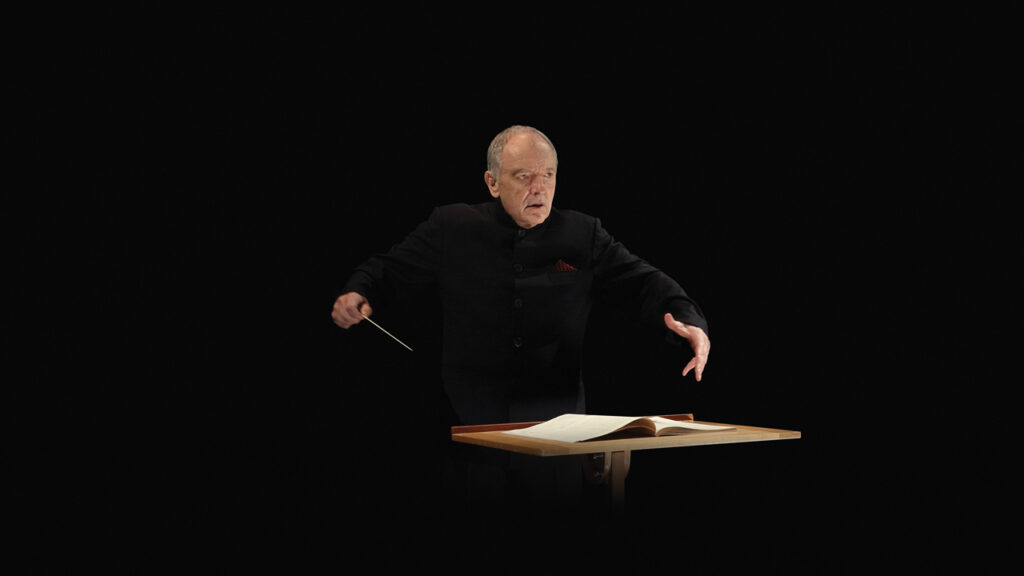

In anticipation of The Final Forte, PBS Wisconsin spoke with MSO music director, John DeMain, who helped start the televised competition in 2007. DeMain has had a long, distinguished career conducting music, and will be stepping down as music director of the MSO at the end of the 2025-26 season. Among his many accomplishments, DeMain conducted well-regarded productions of Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess” with orchestras around the world. He conducted more than 400 performances of the show.

PBS Wisconsin: What’s your favorite part of working with the students?

John DeMain: I remember the first time I played with a symphony orchestra. It was cathartic. When you’re learning a concerto, you dream someday of actually playing it with an orchestra rather than just with a pianist. If they don’t win, the kids will tell you that having the chance to play with the orchestra is more important than the money.

But what’s interesting is when you’re judging the semi-finals, you’re looking to make sure that they have the kind of rhythmic stability and awareness of what the orchestra is doing.

A couple of times people have won, and at first they had no sense of how to work with the orchestra. We rehearse on Monday, then I send them home with notes, and they change almost overnight. Whatever issues there are, we talk about it, and then by Wednesday night, they’re eradicated because these kids are so bright. You watch them grow so quickly.

The other thing that impresses me — because I certainly am not made up like these kids are — there’s no nerves. I mean, if there are nerves, I don’t see them. My piano teacher at Juilliard used to say, “When you’re 14 you don’t know how hard something is. When you’re 50, you do, and when you’re 80, like me, it’s too late.”

The 2024 “Final Forte” finalists are (from left to right): André Peck, a freshman from La Crosse playing piano, Katarina Kenney, a freshman from Madison playing cello, Elliot Lesperance, a junior from Oregon playing marimba, and Jane Story, a junior from Stevens Point playing violin.

PBS Wisconsin: Do you feel a strong distinction between working with the young artists versus working with the more seasoned professionals?

DeMain: You’re not going to expect a 14-year-old to play with the maturity of a 40-year-old artist with a lot of experience in terms of emotional depth of interpretation. But, that’s going to develop over the years. And, they won’t get to the finals unless they show extraordinary musical instincts. I’m just amazed at what they can do already. The four finalists this year are simply spectacular.

But, on the other hand, if you want to be a virtuoso, you don’t start when you’re 19. My piano teacher at Juilliard told me when I was entering at 18, “It’s kind of late for you to be just getting serious about this now. You need to be a virtuoso by the time you’re 14, or it’s too late.” These kids are that.

Another thing that amazes me about these young people is the fact that this is not their only interest. Usually they’re going to have a double major in college, which I heartily applaud. I think they play well enough already that they could get a job in any orchestra, but those jobs are scarce. So, the fact that they take on another major I think is really great.

PBS Wisconsin: Is that the biggest challenge to mature as a musician, is getting the emotional interpretation of the music correct?

DeMain: Well, I think that’s in anything you conduct, to capture the style, I mean. Debussy is different from Beethoven. Mahler is different from Brahms.

Analysis is everything. Leonard Bernstein used to say to us when we had a master class with him, “You have to study every bar of music until you feel like the notes that are in that measure are inevitable, and there’s no other possible notes, and you completely digest this and make it your own.”

So, you have to live with the piece for a while. The more musical experience you have as you get older the better off you are. Then, when you’re hearing a piece of music, you can immediately identify where it’s coming from. You know where this composer is being inspired. For example, if I do a piece of Mozart right now, and I haven’t done it before, I can learn it in an instant, because in any given measure I know his bag of tricks. After a while, you recognize Brahms and what’s required of that, and so on.

PBS Wisconsin: Can you tell us who or what inspired you to start playing the piano?

DeMain: When I was 2 years old, I had a boy soprano voice, and I would go up in the choir of this Italian church. Since it was a lady’s choir, my voice blended in with them and I’d go up and sing the benediction.

Then when I was 5 years old, I sang a solo in kindergarten, “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” and my picture was in the newspaper. My parents understood that I had a special musical gift.

My father was a steel worker living off of budget envelopes. There was no money in the family, but they sacrificed. They got a piano and started me on lessons and I just chewed it up. I became a great sight reader, but I wanted to be able to accompany myself singing. After about two or three years, the teacher from the company where we bought the piano, called up my mother and said, “I’ve taught him everything I can teach him. He’s got to have a real teacher — an artist teacher.”

Then there was Herman and Blanche Gruce, who were living in Youngstown, Ohio, at the time. He took me on at age 9, I sat with him for about 3 years, and then he died, unfortunately. I continued with Blanche, and that’s when I started studying the piano really seriously.

But all through high school I had so many interests like speech and debate. I was putting on shows at school. I was in shows at the community theater, and that’s something that contributed to me conducting “Porgy and Bess.” When I was 14 years old I conducted “Brigadoon” with an orchestra at the community theater, and everybody in the cast was old enough to be my grandparents. But, they all let me do it because they saw I could do it.

PBS Wisconsin: What are the challenges of “Porgy and Bess” as a musical piece?

DeMain: Style. Is it a musical, or is it an opera? The source material was from folk music and Broadway, but it’s carved and shaped like a classical composition.

I understood it to be an opera right from the beginning, but it’s jazz infused. For me the closest analogy is “Carmen.” The main tunes in that opera are all informed by the dances, and the same thing is true for “Porgy and Bess.”

For example, when you sing “Bess, You is My Woman Now” the cellos are creating these dance rhythms underneath it. You want to have that lyrical legato, that operatic line going through, but you also want to feel this resource that’s underneath that gives it its life pulse, and that is based in dance.

The show has every challenge for a conductor that you could think of. There are wicked tempo changes at every turn. For example, Gershwin used a technique that Berg used at the same time in “Lulu,” and that was where someone talks and then someone sings. The white people in “Porgy” did not sing. It takes a real technique to know how to do that — to stop and start.

Plus, the different twentieth century musical styles that are there are a challenge. One minute it sounds like Stravinsky, and the next minute it’s very jazzy. I think it’s important that you have a broad musical background in order to conduct the piece. Fortunately, today, the musicians sitting in an orchestra have that background. People growing up today play all kinds of music. That’s the fun of it.

PBS Wisconsin: What do you think uniquely prepared you to conduct “Porgy and Bess”?

When I was growing up, I was studying classical music, but when I went to the classroom, my peers would ask, “Could you play ‘Diana’ by Paul Anka?” Or “Rock Around The Clock” by Bill Haley and his Comets? I’m so old now. [laughs] I played the latest pop songs for my peers, and I went home and practiced my Beethoven sonata. And I like to sing! My parents would buy me these “Jumbo Notes” of the popular songs of the day, and I would accompany myself singing.

So right from the beginning it was a meld of musical styles that I was dealing with all the time and never even thinking twice about it. I consider myself an “American musician,” and I would say that most other American musicians are probably like me.

In high school, I was at the community theater every night, putting on St. Patrick’s Day shows. I know every Irish song after attending Catholic school. Then, in the summer I was conducting Broadway musicals with big stars, and accompanying the auditions. I was playing chamber music with members of the Juilliard orchestra and going around doing educational programs around New York City. I’m practicing four hours a day, and 10 o’clock at night would come along and I would think, “Who are you? What are you? You’re bouncing around all these different kinds of music all day long. Who’s the real you?”

Then I got my first job at the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra as a conductor. The former music director, Dennis Russell Davies, was called to the Netherlands Opera’s unexpectedly. Now all of a sudden, I’m doing most of the season in Saint Paul.

One of the things on the season was a piece called “Vox Populus, Vox Crapulus,” a work by a Canadian composer, Sydney Hodgkinson. It was a world premiere of the piece, and he called for a rock group, chamber orchestra, actors, opera singers, and quadraphonic stereo sound — the kitchen sink.

It was by a classical composer. The way this piece was shaped, it created an overview of musical styles of the twentieth century. Every kind of study you could imagine. And I thought, “Aren’t you lucky you did all those things?” That’s why “Porgy” came so easily to me; I knew what every style was because I had encountered it.

PBS Wisconsin: What’s it been like to be regarded as an expert in your field?

DeMain: I don’t concentrate on that. I was recently at a eulogy for Steve Fleischman, who was director of the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art for such a long time. I remember what a lovely man he was, and what kept coming up at the eulogy was his humility and the fact that he never behaved like a boss but rather the head of a family. That’s how I’ve tried to be at MSO these last 30 years.

Everybody is working to put on live classical, symphonic concerts, and everybody’s passionate about what they’re doing. So, I want to lead in that, and I want to make the people involved have a really great experience. I don’t want to dominate.

When they’ve finished playing a concert, I want the orchestra to really feel like they did something, and they used themselves, and they go home and feel really good about it.

PBS Wisconsin: What do you hope to leave behind as your legacy when you step down as the director of MSO?

DeMain: I don’t like to brag, but I know that the Madison Symphony Orchestra is a different orchestra than when I came here 30 years ago, and they’re playing pretty fabulously. And I know that my work was a catalyst for building the Overture Center.

I tripled the audience. Before COVID-19, we went from one concert to three per weekend. Considering that this is the size of a town that anywhere else in the United States would only do one show per weekend in a 2,000 seat theater is something I’m very proud of sustaining. I wanted to take advantage of the fact that Madison still had music education, which meant it had a feeder system. It had kids who loved classical music and adults who loved classical music.

I learned from my boss, the general director of Houston Grand Opera. At one point, he was applying to take over the New York City Opera. I asked, “Why do you want to go there?” And, he said, “Because I think I can make a difference.” I felt the same way 30 years ago when I heard the Madison Symphony playing. There were strengths and weaknesses, and I thought, “I’ve made a difference in Houston with my freelance work. I think I can do that here.”

In those days, when we had openings in the orchestra, the people auditioning were the students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. We had an audition last week for principal horn. They came in from all over the country. I’m very proud of that, and I did it with a fierce devotion to the classical repertoire.

But, most importantly, I will be remembered as someone who did my work in a very healthy working atmosphere, that I respected my musicians, and that was very important to me, both here and in opera.

Passport

Passport

What do you think?

I would love to get your thoughts, suggestions, and questions in the comments below. Thanks for sharing!

Tara Lovdahl