On "Here & Now," Nathan Denzin unpacks why increasing numbers of migrants are heading to Whitewater, Erin Barbato discusses policies and politics of asylum and Alyssa Ratlege describes impacts of declining higher education access in rural areas. Plus, Zac Schultz covers updates on the Wisconsin Supreme Court's submitted redistricting maps. Listen to the entire episode of "Here & Now" for February 2, 2024.

Subscribe

Announcer:

The following program is a PBS Wisconsin original production. You’re watching “Here & Now” 2024 election coverage.

Frederica Freyberg:

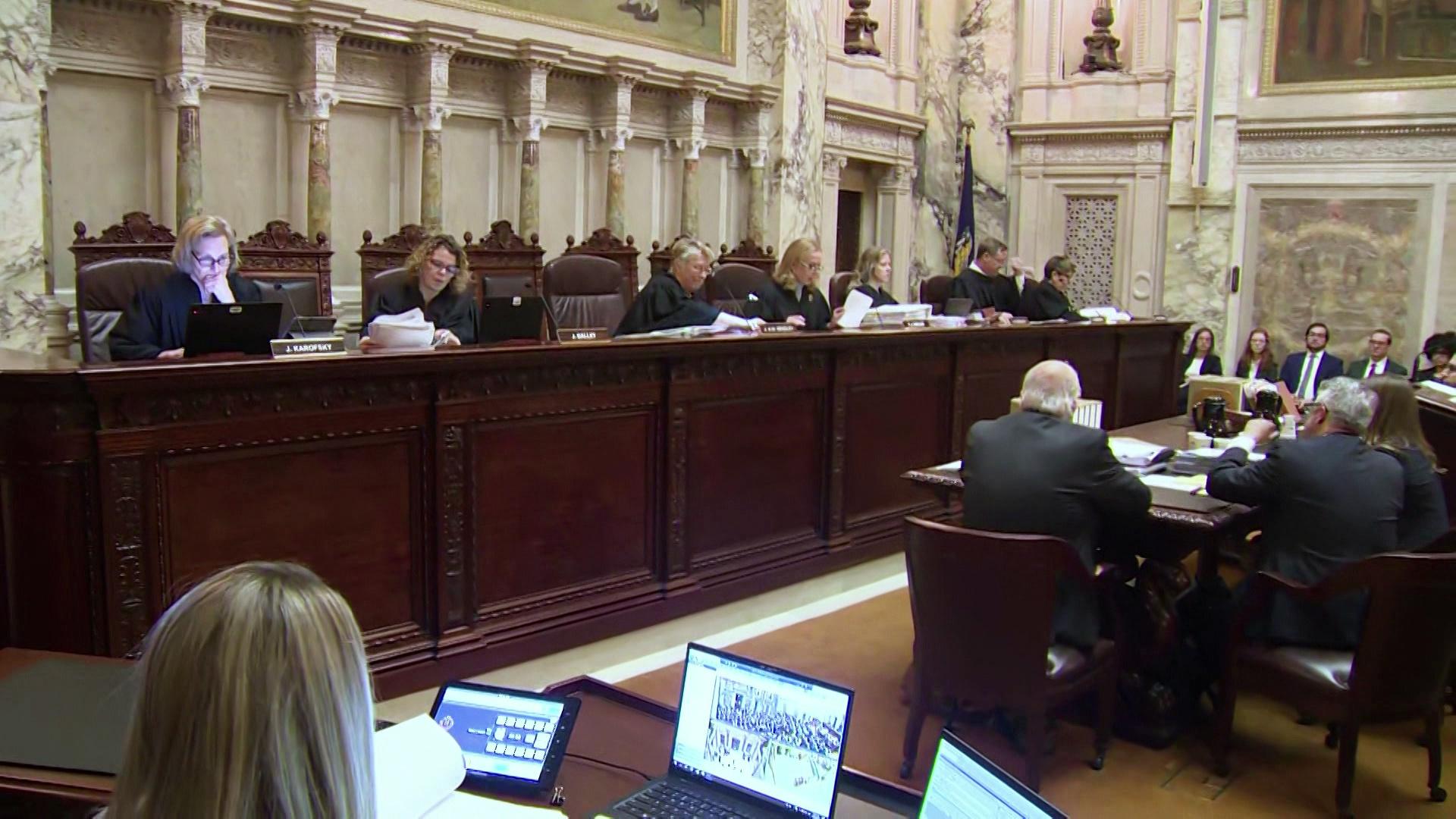

Expert recommendations for state voting maps are in. And the Wisconsin Supreme Court will have the final word on which maps become law.

I’m Frederica Freyberg. Tonight on “Here & Now,” a closer look at the district lines to be voted on by the Supreme Court. Then, how a small community is adapting to a sudden influx of migrants, and the reality of policies at the southern border. And finally, analysis on the long-term impacts of waning access to rural higher education. It’s “Here & Now” for February 2.

Announcer:

Funding for “Here & Now” is provided by the Focus Fund for Journalism and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

Frederica Freyberg:

Wisconsin is on course to have new voting maps in short order. Late this week, consultants hired by the state Supreme Court rejected two of the map submissions as being partisan gerrymanders and said the rest could meet muster with the high court. For details on this, we turn to senior political reporter Zac Schultz at the Capitol. Hi Zac.

Zac Schultz:

Hello Fred.

Frederica Freyberg:

So which two maps represent partisan gerrymander according to these consultants?

Zac Schultz:

The first one really shouldn’t come as any surprise and that is the Republican map, the Republican legislators’ map, which is the most closely related to the current maps that are in place that the Supreme Court already said were gerrymandered. The other maps are from what’s called the Johnson Intervenors, which is actually maps drawn by the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty, or WILL. That’s a conservative law firm. They hedged their bets somewhere in between some of the maps drawn by the more liberal or Democratic groups in this case and their Republican legislators’ maps, but still pretty much made for slam dunk majorities for the Republicans if their maps had been adopted.

Frederica Freyberg:

That’s something the consultants called stealth gerrymandering, I think, in their report.

Zac Schultz:

Yes, and that’s because the WILL maps met all of the criteria that are determined by the state constitution. They’re contiguous. They kept most of the municipal communities of interest together, the population, all those things were there, but they still were drawn in a way that would pretty much guarantee Republican majorities and, in some cases, possible super majorities.

Frederica Freyberg:

And so the consultants’ review on this is not sitting well with Republican mapmakers, saying their maps were rejected because they didn’t produce Democratic outcomes that this court wants.

Zac Schultz:

Well, I think they’re speaking to their audience, their voters, their base, their donors and possibly hoping to speak to the U.S. Supreme Court where they’re hoping this appeal will be heard and then one of their two preferred maps would ultimately be chosen by the high court in the land. But the honest reality is that every independent analyst, every expert, most people that understand this issue at all have looked at these maps for the last decade plus and said these are gerrymanders that favor Republicans. By how much has always been the question. Was the two-thirds supermajority in the Senate entirely a gerrymander? Probably not, what the experts say is that but a solid portion of that is because of the gerrymander that was drawn in to favor Republicans in districts that were guaranteed to elect them.

Frederica Freyberg:

So as to the other four maps from Democrats and others, the experts deemed them not partisan gerrymanders but is not necessarily perfect, either.

Zac Schultz:

That’s right. There were differences between all four maps. The experts, most of their 25-page review was actually scoring in their analysis of all the different maps according to a number of rhetoric rubrics. Mostly look at partisan fairness, which is kind of the new standard that this court has introduced for this process to say in a 50/50 top of the ballot state, which is what Wisconsin is, what would be the most fair outcome and how would that be represented by how the districts looked. And they said that according to some analysis on this one, looking at all the old elections for the past seven years, this map was better, that map was a little better over here, so different scores for different areas but otherwise roughly the same. None of them stood out well and above to the others, so they said the Supreme Court can pick from them if they want.

Frederica Freyberg:

So the consultants also rejected Republican claims that their majorities in the Legislature are due to Democratic support being concentrated in cities while the GOP has this broader support out-state. The consultants said, “Geography is not destiny.” Unpack this for us.

Zac Schultz:

This is something we’ve heard over and over, and we’ve reported on for years and that there is a little bit of a geographic bias for Republicans in Wisconsin. The question is, how much? In a neutral, fair map, we’ve had experts from the UW say that Republicans would win somewhere between 50 and maybe 55 seats in an average year if the maps were all drawn fairly. And in this case, the experts said that that was something that they should be looking at but you can make fair maps without having everything tilted one way. So it shouldn’t give the Republicans 66 seats in the Assembly, but maybe somewhere in the low to mid 50s, which is a giant difference when we’re talking about governing in this body.

Frederica Freyberg:

So what happens now?

Zac Schultz:

Well, now we wait. There is one week for the other intervenors and plaintiffs and defendants in this case to file their responses to the experts. That’s due next Thursday. After that, the court could ask the experts to draw or adjust. The experts did not submit their own version saying they thought the four maps that they proposed that were in there were good enough but they can make adjustments if the court wants. The court could narrow it down. The court could make a decision. It really is up to the court and we don’t know what happens after that.

Frederica Freyberg:

The consultants also said they could take a crack at making these maps in short order.

Zac Schultz:

That’s right.

Frederica Freyberg:

All right. Zac Schultz, thanks very much.

Zac Schultz:

Thanks, Fred.

Frederica Freyberg:

In other news, Whitewater made national headlines last month after a Breitbart news story claimed a thousand migrants had been dropped on the city. But officials say the truth of the matter is much more complicated. “Here & Now” reporter Nathan Denzin has more.

Dan Meyer:

Our case here in Whitewater is very unique.

Brienne Brown:

I started noticing the wave of migrants probably — it was during the pandemic.

Jorge Islas-Martinez:

Why immigrants immigrate to a place is because as humans, we are looking for a better life.

Nathan Denzin:

Whitewater has seen a wave of migration from the southern border with Mexico over the past two years, but this case is not like recent headlines where immigrants are being chartered to northern communities like Chicago.

Dan Meyer:

I’ve had a lot of people ask, “Okay, where are the buses dropping people off?” That’s not happening here.

Brienne Brown:

It was, like, 50 at first and then it was like another 50 and so it wasn’t like a massive rush.

Nathan Denzin:

But now city officials suspect that there are about 800 to 1,000 migrants from Nicaragua and Venezuela in Whitewater. And Whitewater is not a large city. The 2020 census indicated that about 15,000 people live there. Nearly 8,000 to 10,000 of those are students at the university.

Dan Meyer:

The earliest we really noticed it was, I would say, early 2022.

Nathan Denzin:

Dan Meyer is the chief of police for the city of Whitewater.

Dan Meyer:

We had a family that was found in a 10×10 shed and that was during the wintertime, so January of ’22, so very cold temperatures.

Nathan Denzin:

He says that before they got to Wisconsin, many of the migrants likely had contact with border patrol.

Dan Meyer:

The way the border policies work currently is that when someone crosses, customs identifies them and asks them if there is a sponsor family that they know of that can take them in. So if somebody is able to identify that sponsor family and they can confirm that, they’re essentially provided transportation to that sponsor family.

Nathan Denzin:

When they enter the U.S., they’re technically in deportation proceedings, but with a sponsor family, they’re released until their first court date. That court date is usually several years in the future due to a huge backlog of cases. They can then sponsor other families that they know. The result is a pyramid effect where many families from a small area in Central and South America have come to Whitewater.

Brienne Brown:

Because they’re trying to get out of really unsafe situations and there’s work to be had. There’s spice factories. There are egg factories. There are sod farms. There are chicken farms.

Nathan Denzin:

Brienne Brown is a member of the Whitewater Common Council. Nicaragua and Venezuela are both in violent, political upheaval, driving people out of those countries and into America.

Brienne Brown:

What they were most concerned about was if they walk down the street, they had to have a stack of cash in their pockets because they were always having to pay somebody off to stay safe.

Nathan Denzin:

Upon arriving in Whitewater, their legal limbo makes life extremely difficult.

Brienne Brown:

And most of them are really concerned about the fact that they’re not allowed to work.

Nathan Denzin:

Brown has talked to many migrants who are not allowed to work for the first 100 days that they are in America.

Brienne Brown:

There are a lot of people who are following the rules and only one person is working and everybody else is not.

Jorge Islas-Martinez:

We are going to work to make money and to help our families.

Nathan Denzin:

Jorge Islas-Martinez is an immigrant advocate and a first-generation immigrant from Mexico. He has lived in Whitewater for nearly 30 years.

Jorge Islas-Martinez:

I like to promote education. I like to help others learn how to speak English.

Nathan Denzin:

He says migrants face numerous challenges when they first get to Wisconsin: getting a job, speaking a new language, and having transportation is all top of mind.

Jorge Islas-Martinez:

I know how it feels to be in this country not knowing the language. It is hard. Every single human has a right to succeed. Whatever you are, you have that right.

Nathan Denzin:

But finding a job in rural Wisconsin requires a car, and in Wisconsin, undocumented migrants are not allowed to earn a driver’s license.

Jorge Islas-Martinez:

We don’t have public transportation. The only transportation that we have is the taxi. The taxi only is available here in Whitewater from 7:30 in the morning until 5:00.

Dan Meyer:

I see it as a huge safety issue. I mean, we’re — if we’re having people especially driving in snow for the first time, that is not a good situation.

Brienne Brown:

It’s safer for people to have driver’s licenses. They have to take drivers classes. They have to take a test to make sure they can drive. They have to have insurance.

Jorge Islas-Martinez:

I drove a taxi for a lot of years, but to be honest with you, I learned how to drive once I came here to the United States. I learned what the yellow line means. I learned what the white line means. I know what the broken line means. I learned how I can pass a car. I did not know that in my country.

Dan Meyer:

If somebody is able to come here and take all of the testing, the written test, physically do the driving test so that they are safer as a driver, I’m all for that.

Nathan Denzin:

Nearly 20 states already allow undocumented immigrants to obtain a driver’s license, including Illinois.

Brienne Brown:

I think that it’s something that they really need to look harder at in our Legislature, is just giving those rights back so that everybody is safer.

Nathan Denzin:

Along with drivers’ licenses, city officials say more needs to be done to help Whitewater’s newest immigrant population.

Jorge Islas-Martinez:

I think we have to learn how to help each other. I think we have to learn that we are humans. We are immigrants but we have feelings.

Nathan Denzin:

For “Here & Now,” I’m Nathan Denzin in Whitewater.

Frederica Freyberg:

Next week, a look at what the community is doing to help their new neighbors and why city officials are asking the state and federal government for help. The migrants arriving in Whitewater represent a tiny fraction of people crossing the southern border into the U.S. In December alone, some 300,000 people from Central America and elsewhere reportedly did so. Two and a half million people in 2023.

The crush of people crossing the border is described as a humanitarian crisis. Meanwhile, three million pending asylum cases before U.S. immigration courts means migrants gaining entry at the border wait years for their hearings, all the while living and, after a time, legally working in the U.S. Erin Barbato is the director of the Immigrant Justice Clinic at the University of Wisconsin Law School. She recently visited the border and she joins us now. Thanks a lot for being here.

Erin Barbato:

Thanks for having me.

Frederica Freyberg:

So I understand that you were in Tijuana.

Erin Barbato:

Yes, I was in Tijuana in December to take a close look at what is actually happening on the border and the policies that are in place there right now through the Department of Homeland Security and really looking at how people can access our asylum system and the new policies that are in place.

Frederica Freyberg:

What did you see at the border?

Erin Barbato:

So we visited a number of shelters that were housing people who are in transit attempting to seek refuge in the U.S. And in order to do so right now, they need to apply for an appointment with an app, a CBP One app. And many of the people we met with have been waiting for months in order to access that appointment, but it’s — our government is encouraging people to go through a regular route to enter the U.S. to seek protection, but it is causing a lot of people to wait very long in Mexico before they can even access our asylum system.

Frederica Freyberg:

Why are so many millions of people wanting to gain entry into the U.S.?

Erin Barbato:

I mean, that’s a good question. I think when you look at it, we live in a great country and people are suffering all over the world and so if we were living in a country where no one wanted to come, that would probably be an issue, but we’re living in a country where we do have opportunity for people. And peoples’ lives are in danger in certain countries. Not everybody coming will qualify for asylum but many of them do.

Frederica Freyberg:

What policies have changed allowing this more recent crush?

Erin Barbato:

I’m not sure if the policies have changed. It’s difficult in the past few years compare numbers considering that the border was closed under Title 42 for so long and now that the border is — it’s not open, but it’s functioning under what’s called Title 8, which is a law that governs our asylum process allowing people to seek asylum at our southern border which they can’t really do right now unless they have a CBP One app appointment. One other change that potentially has some validity in helping people access the asylum system in a more regular manner is the opening of these [Spanish word] mobile offices in Colombia, Guatemala and Costa Rica, and will allow certain people with strong cases to apply for refugee status there and then fly to the U.S. And so it could take some pressure off the border as well as our asylum system.

Frederica Freyberg:

Meanwhile, there’s so much discussion around this and the numbers of people crossing into the United States. What happens if, through some executive or legislative action, the borders close? Is that even possible?

Erin Barbato:

It seems that it is possibly, potentially whether our president has the ability under the laws to close the border I think is a question that will be litigated in court. Our laws say that people have the right to seek asylum in the U.S. as well as to enter the border if they have an employment-based visa or even a visitor visa to visit a family. So it could have really harsh consequences on separating families and also putting more people in danger, but that may happen.

Frederica Freyberg:

Short of closing the border, does it seem likely that highly restrictive laws will be put in place at this time?

Erin Barbato:

I know that they’ve been discussed. I’m not sure that they’ve ever worked before. More deterrents, more enforcement doesn’t seem to deter people to necessarily come from the U.S. and I think there might be a better way to look at a more humanitarian solution.

Frederica Freyberg:

Why do people wait so long to have their cases heard?

Erin Barbato:

The backlog within our administrative law system in the immigration courts is — it’s very long. And so people, even with the strongest asylum cases, are waiting years in order to access the benefits that they are entitled to under our laws, and so it makes the system very difficult to manage. People may miss their court hearings because the court hearings get changed all of the time and people don’t have an attorney when they’re in the process unless they can afford one or find a pro bono one. It’s a very difficult system to navigate and it’s not going quickly for people who are eligible.

Frederica Freyberg:

Once they get to that hearing, how likely is it that people seeking asylum will be granted it?

Erin Barbato:

You know, the percentages differ where you’re in the U.S. The numbers — the judges’ percentages of approvals are available across the country. So it’s hard to say exactly, but it’s difficult. It’s not — the percentages are not high for the people that receive asylum. If you’re represented by an attorney, you’re more likely to receive asylum because they know what the law is, what the judge is looking for based on your story, but it’s a very complicated, difficult process and people do not just — aren’t just given papers. It takes years. It takes months to prepare. It’s a very difficult process.

Frederica Freyberg:

Meanwhile, people who are awaiting that hearing, they can get authorization to work legally?

Erin Barbato:

Yes. Normally, depending on what process they’re going through, but you have to wait a number of months, six months to a year normally, to obtain a work permit to work in the U.S. Once you have that you’re here with authorization. You can work. You can get a driver’s license. You can get a social security number, but you’re not here permanently. You can’t leave the U.S. You don’t have access to public benefits. You are here temporarily and maybe it’s for years waiting to access the asylum system, but the work permit does allow people to participate in society and support themselves.

Frederica Freyberg:

All right. We need to leave it there. Erin Barbato, thanks very much.

Erin Barbato:

Thanks so much for having me.

Frederica Freyberg:

In education news, the number of UW two-year campuses going to on-line classes instead of in-person instruction has risen to three. At West Bend, Fond du Lac and Marinette. UW-Richland has closed altogether. The Marinette campus is part of UW-Green Bay and its chancellor, Michael Alexander, says the writing was on the wall, what with declining enrollment and competition for students from the nearby Northeast Wisconsin Technical College.

Michael Alexander:

There has to be access points to education. UW-Green Bay has to have a presence in northern Wisconsin. And we’re investing in the high schools there, to be clear. So with our rising phoenix program and other things that we do, our students particularly who are interested in college to get them a head start on the college experience, to be able to offer classes that the high schools might not otherwise be able to offer with a smaller population in the high school. Right? These are things that we absolutely are trying to do to help that region. Because it does matter. Right? We can’t look at the problem and just throw our hands up. We have to find a way to actually make it better and that’s what we’re trying to do here. And, again, I go back to the NWTC issue. Right? We think a little differently about this sometimes, but I want to be clear, if most of those classes, if not all of those classes, those 14 classes, there’s a class that’s pretty much being identically taught by NWTC. Why are we duplicating our educational resources in an area that is harder to serve because of how spread out it is with the number of people that are there and the population? You’ve got to think differently about how we access — give access to those people who want it.

Frederica Freyberg:

So what does the closure of two-year campuses to in-person classes across Wisconsin mean for access and degree attainment for students? We check in with a national non-partisan, nonprofit group MDRC, and its research associate in the area of rural higher education, Alyssa Ratledge. Thanks very much for being here.

Alyssa Ratledge:

Thank you for having me.

Frederica Freyberg:

So you have written that rural colleges matter. How so?

Alyssa Ratledge:

Rural colleges are often the only access point to higher education post-secondary training and workforce training for people who live in rural areas. Many people living in rural areas are simply unable to move away to go to college and they do not always have on-line access to be able to take up on-line offerings. So the ability to go to a college and, again, these might be distant, we might be traveling 25, 50, even a hundred miles to college, but it still means folks can stay where they are from, where their families are located. When you are closing campuses, it can be really challenging for those folks to continue to engage or to achieve the postsecondary credential that they’re interested in.

Frederica Freyberg:

Because in the end, what happens when there are what you call education deserts?

Alyssa Ratledge:

Education deserts have a chilling effect on students’ likelihood of going to college, but also importantly, their likelihood of completing college. Nationally, most students who are attending college are doing so within about 25 miles of their home. It’s not really these days the traditional sense of being 18 and going off to college and living on campus. These days, most college students are commuting and a lot of them particularly in the two-year space are attending part-time, and today’s college student is much older than the traditional conception. Those folks are not going to pick up and leave. They often have families and jobs and responsibilities, nor do they want to leave. Oftentimes we hear that our rural folks want to stay where they are, contribute to the local community, and having workforce training or a college degree can help them do that in a meaningful way if they’re able to access it.

Frederica Freyberg:

So the UW-Green Bay two-year branch in Marinette is going mostly on-line. Doesn’t that still afford access to rural students?

Alyssa Ratledge:

There are many rural students for whom on-line access is going to be enough. And when we think about our students who are coming out of high school, have good access, have good knowledge of the internet, yes, that can be a good option for them. However, there are going to be a lot of folks that are not going to be able to take that up. Oftentimes that’s older folks or people who are living in very remote and rural fringe locations where they simply don’t have reliable broadband or, in some places, don’t have internet access at all. There are still parts of the country without reliable internet access and many of the on-line course offerings are going to require a high-speed connection or the ability to download documents that just is out of reach for people who are living really off the grid.

Frederica Freyberg:

So what about the fact that for the campuses that are realigning or even closing, the problem is really low enrollment, which makes maintaining the whole kind of campus infrastructure untenable. Doesn’t it make sense to basically downsize for the university system?

Alyssa Ratledge:

It may make sense if there’s not a willingness to invest in supporting those campuses at the state level, yes, it can be an untenable situation when you look at the bottom line and the budgets. That is ultimately a philosophical question we have to grapple with. Right? Are we willing to fund places that we are going to be seeing budgets really struggling to make ends meet given the reduction in students at the cost of potentially some of those students are going to struggle with or be unable to complete a college degree, if that location is closed.

Frederica Freyberg:

So a recent paper from the Federal Reserve discussed how employment and manufacturing in the agricultural sectors has decreased in Wisconsin over the past 10 years. Where does that leave people who haven’t upskilled for a changing economy, especially in rural parts of our state?

Alyssa Ratledge:

Yeah. It is an enormous challenge. It’s a great question. We see this in a lot of places across the country, where natural resource economies or agricultural economies are changing and we also know that it is harder than ever for agricultural workers and family farms to make ends meet. At the same time, there is an additional technological component to many of those jobs that could be greatly benefited from some additional workforce training or technological training. So leaving folks in those areas without access to that training can make it really difficult for them to compete in a changing economy. This is especially true for those folks and those communities where people want to stay where they are. Right? There’s always the option, of course, to move to a big city, but that just continues to hollow our rural towns and counties out. So if we want to keep the sustainable economy in these places, we need to figure out how we can support folks to be able to afford and completely upskilling, whether that’s a traditional college degree or a trade certificate or workforce training.

Frederica Freyberg:

All right. We leave it there. Alyssa Ratledge, thanks very much.

Alyssa Ratledge:

Thank you.

Frederica Freyberg:

For more on this and other issues facing Wisconsin, visit our website at PBSwisconsin.org and then click on the news tab. That’s our program for tonight. I’m Frederica Freyberg. Have a good weekend.

Announcer:

Funding for “Here & Now” is provided by the Focus Fund for Journalism and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us