- Donate

- Watch

-

-

-

Explore Online

-

-

PBS

Passport

PassportSupport PBS Wisconsin and gain extended access to many of your favorite PBS shows & films.

-

- TV Schedule

- News

- Education

- Support Us

-

Premiering 7 p.m. Monday, Nov. 28, Jerry Apps Food & Memories marks 10 years of Jerry Apps on PBS Wisconsin. In this all-new television special, Jerry and his daughter, author and educator Susan Apps-Bodilly share family stories through food his mother, Eleanor, painstakingly prepared for the family.

In anticipation of the premiere, Jerry Apps spoke with PBS Wisconsin about his career as a writer and how his agricultural upbringing continues to influence his perspective.

PBS Wisconsin: Did you enjoy reading as a kid?

Apps: My passion for reading goes clear back to when I was five years old as a student at the one-room country school. What a fantastic world opened up for this little country kid who had never really been out of Waushara County. I’ve never gotten over the wonderful feeling that I get when I open a book, and I read probably a book a week of some kind or another. Yet today my passion has always been storytelling.

PBS Wisconsin: Did your parents read often?

Apps: Not really. My dad was more of a reader than my mom, although she did read to me as a little kid and to my brothers — books like Uncle Wiggily. But aside from the Bible, we had very few books. My dad would read all the farm papers, like the Wisconsin Agriculturalist, Successful Farming and Farm Journal to keep up on what was happening in farming. But I don’t think I’d ever seen my dad read a book.

Eleanor and Herman Apps. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

PBS Wisconsin: Where did you discover your passion for storytelling?

Apps: When the neighbors got together, whether it was for threshing, silo filling or cutting wood, they would start telling stories. These men, not only were they entertaining each other, but they were informing each other. You could learn so much from a person by the stories that person tells beyond the one liners, “Oh, I’m not feeling well today,” or that sort of thing. The story takes you deeper — takes you into a place where the person may not even be aware of what he or she is sharing.

Stories are powerful. I taught storytelling for 41 years in creative writing workshops trying to help people get in touch with their stories, because we are our story. And sometimes we want to keep it in the background; we don’t want folks to know about it.

For example, I had a number of World War II and Korean War veterans in my classes, and for some of them, they had never told their story about what it was like to be in combat. I will never forget this: one of my students was crying as he told us about what it was like to go ashore in the first wave and see your buddy shot, and you are still alive and you wonder why. And his wife said to me, “He’s never been the same since that experience he had with you. He’s a different person. He’s come more alive; he’s more friendly.” Those are powerful stories.

Threshing grain. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

PBS Wisconsin: How did you get into writing?

Apps: In January of 1947, I came down with polio and that changed my life forever because from January until April, my right leg was paralyzed. When I started high school I could barely walk and all of the boys were expected to go out for baseball. And I’m standing up to the plate — how I remember all this is beyond me, but I do — and Cliff Simonson was the pitcher. And if you were a freshman, he had the job of pitching a ball as close to your nose as he could to see if you would react.

Well, Cliff wound up and pitched one of his fastballs and of course it hit me right alongside the head, knocked me out cold. As I’m coming to, I look around and they are all looking down at me. Paul Wright was the coach — wonderful man, really — and he looked at me and said, “Jerry, I don’t think you’re going to make the baseball team.” He was so right.

But then days later he said, “You know, Jerry, why don’t you take typewriting?” I said, “Typewriting!? That’s a girls class!” But I took type writing, and I’m the only boy, and I’m scared to death. These are LC Smith typewriters and they’re manual typewriters; you gotta really work on it, or they don’t work. But because I was milking cows by hand, I found with my stubby little fingers, I could make that old typewriter just whistle.

The typewriting class was also the newspaper office. We produced The Rosebud, as it was called. And we produced it on a hectograph machine, which you’ve probably never heard of because it predated the mimeograph. By the time I’m a junior, I’m the assistant editor. By the time I’m a senior, I am the editor and I’m writing all the editorials.

I really had a good time. However, once you have polio, you always have polio because you feel so absolutely worthless when you’re 12 years old and you cannot do what every other boy is doing. And even though I was writing and having fun, I wasn’t doing the important things in my mind. I wasn’t earning a “W” to put on my [letterman] sweater, which was a big deal in those days. I did earn a “W,” but it was for public speaking.

And because I couldn’t do sports and all that other stuff, I studied a lot — read a lot — and I was valedictorian of my class. I got a scholarship to the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Guess what it was worth: $62 and 50 cents. It paid my tuition and [without it] I never ever would have gone to college. It was unheard of for my family for anyone to go to college. My goodness, nobody even went to high school. It was a great thing to have even graduated from eighth grade.

Jerry Apps pulls his brothers in a wagon. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

PBS Wisconsin: Was it difficult for your dad to see you go to college instead of continuing with farming?

Apps: It was very hard because he expected, as most farmers did, that the oldest son should stay on the farm. And to tell the truth, I would have done that. I liked farming. I still have a farm, believe it or not. I’ve got our oldest son Steve doing most of the work. It’s a tree farm with no animals there, other than wild ones. But no, I love farming. The idea of being outside and producing food, so much of it is me. I’ve never gotten over that — I never will.

PBS Wisconsin: So really, you just merged two passions into one different career.

Apps: That’s true, and so rather than experience farming directly every day, I experience it by writing about it. Not only have I written my stories but I’ve done a whale of a lot of historical digging. I wrote Wisconsin Agriculture: A History, which took me four years to research. It was like writing two PhD dissertations. I’ve written about the history of farming with horses, the history of the Ringling brothers circus, and the history of one-room country schools, all of which I dug as deep as I could because I think it’s important.

And I tell this to my writing students: you don’t know where you’re going unless you know where you’ve been. And digging out your personal history is one way to do that. For our society to know where it’s going, it’s got to know where it’s been. We build on the foundation of our history.

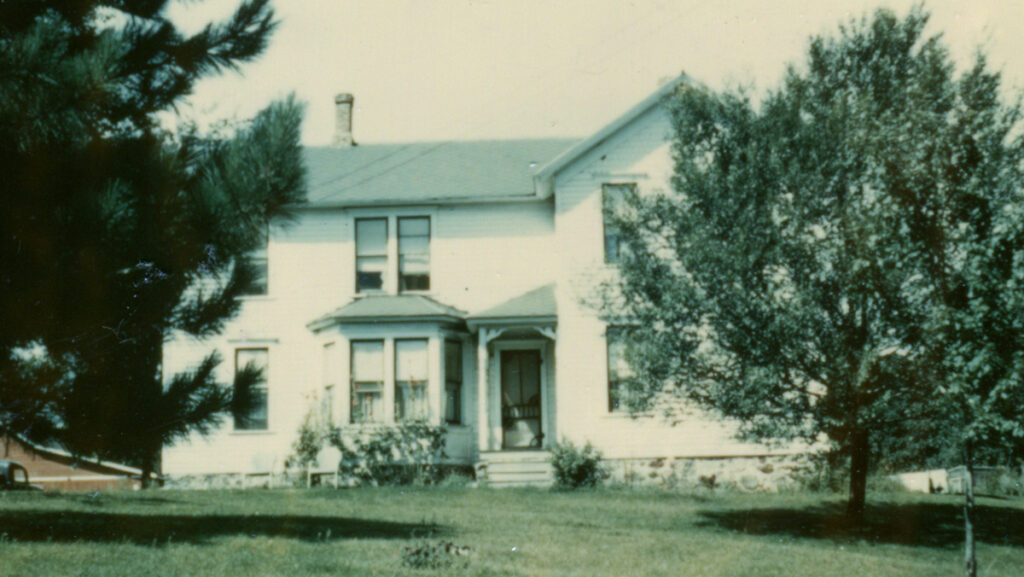

Apps family farmhouse. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

PBS Wisconsin: How do you think the changing landscapes for farmers has changed the whole state?

Apps: I’m not too happy to see the family farms, as I knew them, disappear. They are still disappearing; we’re down to a precious few medium-sized farms left. And that’s one of the books that I’m working on right now: what needs to happen to rejuvenate, to re-examine, to re-explore what farm life ought to be like as we move ahead.

And this is maybe extreme, but I believe agriculture has lost its way. It doesn’t know where it’s been. It doesn’t believe that where it’s been is important, and it doesn’t know where it’s going. The relationship to the environment, to me, is essential. We’ve gotta pay attention to the land. We’ve got to recognize that land is something more than dirt. That sounds sort of silly, and it sounds like an old professor shooting off his mouth but, unless we do that, we’re going to end up hungry.

And we’re going to end up with this cleavage between rural and urban America becoming larger.

To me it’s everybody’s problem – what’s happening in agriculture – not just those handful of people who still live and work on the land. Agriculture has got to rediscover itself. We cannot abuse the land and we cannot abuse our water, for heaven’s sake! If we don’t pay attention to climate change — oh my gosh. It’s just all around us right now, and agriculture is right in the middle of it.

Apps family ice fishing trip. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

PBS Wisconsin: Do you think that people have less of a desire to be farmers today?

Apps: That’s a good question to contemplate because, yes, you could say that. But also, I am hearing from more and more people — and COVID helped this, if you can give COVID some credit — a number of people discovered when working at home, because of COVID, that they didn’t have to be in a high-rise apartment in downtown Manhattan. They could be upstate New York in a little country town if it had Wi-Fi connection. Maybe they’d have a big garden and grow a lot of their food.

There are a number of examples, especially in the area of vegetable growing, where the acreages are relatively small and they’re selling to stores and restaurants. The idea of farm-to-table is catching on. Food cooperatives, where farmers come together with restaurants and so on, that whole idea is going prominent. So there’s hope.

There are some good examples, but unfortunately we’ve got a handful of corporations controlling what’s happening in much of agriculture today and that’s got to change.

My newest novel is called Settler’s Valley, and it’s about a group of veterans who got together at a hospital in Washington and they came out to Wisconsin to this little town in Aimes County, which I invented. And they’re all physically or mentally abused. And they’re working on land that has been abused. And as they heal the land, they heal themselves. There’s research to show that. In fact, getting out and just taking a walk in the woods, as far as that’s concerned [can heal you]. I wrote a whole book on gardening, and in there, I talked about how it can do so much more than just provide food.

PBS Wisconsin: Do you still garden?

Apps: We still have a huge garden at our farm, and my son Steve and his wife and Natasha essentially run it. But Susan and her husband help along. I don’t do very much work with it anymore, other than to say, “Well, there’s where you plant the potatoes.” The kids wrote across the back of one of my chairs, “senior advisor.”

Featured blog image of Jerry Apps courtesy of Steve Apps.

I would love to get your thoughts, suggestions, and questions in the comments below. Thanks for sharing!

Keith

Is there a recording of Food and Memories ? I have friends that are not online that would like to see this ?

Tara Lovdahl

Hi Keith,

Yes, “Jerry Apps Food & Memories” is available as a DVD. You can visit pbswisconsin.org/donate to search our online store of pledge thank you gifts. You can also call membership services at 800-422-9707 for assistance.

Thank you!

Tara

Tara Lovdahl

Hi Keith,

There are also two more encore presentations of “Jerry Apps Food & Memories” coming up: https://pbswisconsin.org/watch/pbs-wisconsin-documentaries/jerry-apps-food-memories-wdvyrj/

7 p.m Thursday, Dec. 8 and 7 p.m. Sunday, Dec. 11.

Thank you!

Tara