Mental Health, Trauma and Black Communities

"We can't breathe as a community."—Myra McNair

PODCAST

Angela Fitzgerald sits down with Myra McNair, a licensed therapist, to talk about mental health struggles within Black communities, and how the Black church and financial barriers contribute to these issues. They discuss on how images of Black death, racial trauma, social media and more are provoking a public health crisis for Black communities. They also identify solutions and how finding joy can be a revolutionary act.

Subscribe:

GUEST

Myra McNair

Owner and founder of Anesis Therapy, Myra McNair is a licensed Marriage and Family Therapist (MFT) and trauma specialist. Myra has a bachelor’s degree in biology and a master’s degree in marriage and family therapy with specialties in addiction, depression, anxiety, infant mental health, parent/child attachment, marriage counseling, trauma-informed practices, and cultural interventions.

PODCAST TRANSCRIPT

Speaker: The following program is a PBS Wisconsin original production.

Angela Fitzgerald: Hi. I’m Angela Fitzgerald. This is Why Race Matters. Racial trauma is constant within the Black community. But how have events, such as the killing of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, or the shooting of Jacob Blake, added to this trauma? What about the almost daily barrage of media coverage, YouTube clips, and social media posts showing Black people dying? How does that affect Black mental health? On this episode of Why Race Matters, I’ll chat with Myra McNair, a therapist and trauma specialist, about the anxiety and mental health hurdles Black people face every day. We’ll also talk about the Black church, and the role they can play. Together, we’ll discuss and explore why race matters when we talk about mental health. Thank you for joining us today, Myra.

Myra McNair: Thank you for having me.

Angela Fitzgerald: So, tell me what’s your story?

Myra McNair: I would say it’s a little bit of a long story. I would say it started, really, since I’ve been a little girl. My mother is from Minnesota. We’re from Minnesota. She ran nonprofits. Her one nonprofit was working with homeless youth. So, I really grew up just watching my mom help people, and really be a part of the community. I did always tell myself while I was growing up that I didn’t want to be like her though. So, I majored in this …

Angela Fitzgerald: Like I said, ironically …

Myra McNair: I saw it was so much work. Right? With helping people, being a part of the community in that kind of way.

Angela Fitzgerald: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Myra McNair: So, I majored in biology.

Angela Fitzgerald: Oh!

Myra McNair: Thinking I was going to go into medical school, or be a physician assistant. But then after marrying my husband, moving here to Madison, Wisconsin, my husband is in ministry. So, I saw a lot of mental health issues in the church. There’s always been this narrative in the Black church that if you had Jesus, you didn’t need to have a mental health professional in your life.

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Myra McNair: Right? That you shouldn’t have any mental health issues, you should just pray everything away. You shouldn’t be sad if you have Jesus. Right?

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Myra McNair: So, being a minister’s wife, and seeing all of the issues, and seeing that, it was much more than you could just really pray about. Knowing that we wouldn’t tell that to anyone if there was a physical health issue. Right? We would never just say not to go to your doctor. So, really interested me into the mental health field. So, that’s what really pushed me right into that field.

Angela Fitzgerald: So, that is super interesting, and also super relatable to me, because I was a biochemistry major in undergrad

Myra McNair: Okay. Okay.

Angela Fitzgerald: With the goal of medical school, and then after organic chemistry, it was a wrap. I was like, “Nope! I’m majoring in psychology.”

Myra McNair: Right.

Angela Fitzgerald: It’s been psych ever since then. But you’ve raised an excellent point around how there’s this stigma that’s intersecting with religion, specifically within the Black community, and how that can create a barrier to folks seeking out mental health support. So, in terms of you going into that field, one, can you tell us your … I don’t want to minimize your profession or your certification. So, if you can tell us what that is, and then how you try to circumvent some of those barriers that you’ve mentioned, that might prevent your community from seeking out support?

Myra McNair: Yeah. So, I’m a marriage and family therapist. Graduated right here in Madison at Edgewood College.

Angela Fitzgerald: Woop! Woop!

Myra McNair: I would say there are a lot of different barriers why people don’t receive mental health within our community. So, there is the spiritual or the religious factor, I think, that keeps us, or there’s that stigma that has come from the church. There’s been this stigma, also, that Black people don’t even commit suicide within the church, that people just don’t believe that is something. Because we’ve carried that narrative for so long, we’re seeing these huge spikes in suicide. Right? We’re behind, because we don’t even think that happens within our community.

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Myra McNair: I would say there’s a lot of different barriers though. One is healthcare. Right?

Angela Fitzgerald: Yes.

Myra McNair: One is the stigma that we just carry within our community. We have heard this narrative of, “Well, our ancestors have experienced slavery, and we’re very resilient. We’re very strong.” Right? “If my ancestors have gone through that without any therapy, then why would I need therapy now?” Right? “What I’m going through now isn’t as bad as slavery.” So, we’re strong, we’re resilient. We don’t need this. Right? So, there’s this really negative narrative that we hold within our community about being strong, not needing these extra supports. Also, it has been… psychology has been a very white field. Right?

Angela Fitzgerald: Yes.

Myra McNair: It was created … When we look at psychology, we look at the fathers of psychology.

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Myra McNair: They’re all white males. Right? So, what does psychology, or what does therapy, know about me and my community, about my traumas? Right? We also know that there’s been so much different research on Black people, whether it’s been the healthcare field, with medical, physical health, and then also with psychology. Right? Can I trust a psychologist? Can I trust a therapist? Will they understand? Do I have to educate my therapist about myself and my community before I can even get down to what’s actually my issue and my problems that I’m coming to talk about? Will they call social services on me and my family? So, we know that there’s a historical piece of kids and families being torn apart. So, can I trust that this person will help, or will they be a hindrance?

Angela Fitzgerald: Mm-hmm (affirmative). You have said a mouthful in terms of all the different barriers that are coming from … I mean, there’s a common root to them, but they’re structural. They’re financial.

Myra McNair: Yes.

Angela Fitzgerald: They’re cultural. All of these things that can serve as impediments to people seeking out something that might actually be helpful, on top of if we’re not necessarily taught about mental health and what it means to feel anxious, or what it means to feel depressed, and even recognizing that’s what it is and calling it that, might not even be recognized from folks who would possibly be open to seeking out support. So, I’m wondering, even unpacking the psychology side, in terms of the foundation of psychology being very white-focused, and even now, still being a predominantly white field. What does that mean for you specifically, and your practice, within lovely Madison, which is a predominantly white city?

Myra McNair: Oh, that’s a great question. I would say it’s been really … It’s two different things. One, we’ve had a really huge growth. Right? Which I would say most practices would not experience the type of growth we have. We opened in 2016, and we have close to 30 staff now.

Angela Fitzgerald: Wow. That’s amazing.

Myra McNair: We serve anywhere from 400 to 500 clients right now. So, that’s a really … If you look at the growth trajectory, it’s really, really fast. Right?

Angela Fitzgerald: Good.

Myra McNair: So, I would say we’ve knocked a lot of those barriers down just by being, and by taking up space. But I would say taking up space has not been easy, because there are not a lot of people in our field that look Black and Brown. There are not a lot of people in the field that speak Spanish, or different languages, to be able to reach other communities. So, I would say those have been some major barriers. But the healthcare field, just behind the scenes, the barriers that are there in opening up a clinic, has just been really, really hard. We’ve knocked them down, and we’re here.

Angela Fitzgerald: That’s awesome.

Myra McNair: Like I said, health insurance is a major one, and being able to be paneled with health insurances, so people that have access, that was one barrier, but then also, people need to have health insurance. Right?

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Myra McNair: People will tell you all the time, if they’ve had any family member that has had any type of mental health issues, whether they’re really big or whether they’re really small, healthcare, and getting that access to mental health, is not easy. It’s not an easy system to navigate, whether you’re white, Black, or Brown. I would say that other barrier comes in being Black.

Angela Fitzgerald: Wow. Congratulations on the tremendous growth that you all have experienced, because I personally feel like the need is there. So, just to have a space where people feel like, “I’m comfortable,” like you mentioned earlier, “I don’t have to explain why I’m feeling anxious, or why I’m seeking out your support, because you get it. So, we can just start from there.” It’s probably such a relief to folks, but they’re still working through some of the other challenges that still present.

Myra McNair: Yes.

Angela Fitzgerald: That’s amazing. I was going to ask, too, given that we’re in the state that we’re in, we’re in a pandemic, and there’s been a resurgence, thankfully, of refocused attention on the Black Lives Matter movement, but unfortunately, that’s come at a cost in terms of more lives being lost, and just visually, our being inundated with videos and other images of Black death. Right? I’m wondering, from your professional standpoint, what does that mean to the mental health of Black people now? It’s a lot for everyone, but for our community specifically, what do you think that means, and how is that even showing up, too, within your practice?

Myra McNair: Yeah. This is a huge challenge right now, for Black and Brown people, but especially I would say for Black people. With COVID hitting, it hit our community first, and the numbers of how many Black people are dying from COVID, and being affected, is just … It’s just huge, the impact. So, we had that first to deal with, with the pandemic. Right? That right alone, just that alone, we were seeing an increase at our clinic for mental health. So, that was a lot. Then after the murder of George Floyd, he said, “I can’t breathe.” We’ve heard countless Black men say, “I can’t breathe.” I always explain with COVID, and then with all of the racial unrest, we can’t breathe as a community.

Myra McNair: It was almost like we were suffocating. I think, as clinicians, we process this a lot at our clinic. We were also feeling that. Right? Because we have that shared experience. But then also seeing the impact in our community, and the increase of numbers of people coming in, it was like we couldn’t breathe. That’s the way I explain it. As a community, it’s a shared experience that we’re having right now in the United States. It was to the point, clinically, that I had to even shut down our clinic for a day, just for an extra day, so we could catch our breath a little bit, as clinicians, because like I said, we were having this shared experience with our clients, and we needed some time to slow down, and for some self-care and processing.

Angela Fitzgerald: Good. Good.

Myra McNair: We did that. We did a lot of processing, a lot of we had some yoga online for our staff. It’s just been really, really impactful on everyone’s mental health, I would say, on our families. I think, as clinicians, we were all coming in and just we have so many clinicians of different ages. Right?

Angela Fitzgerald: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

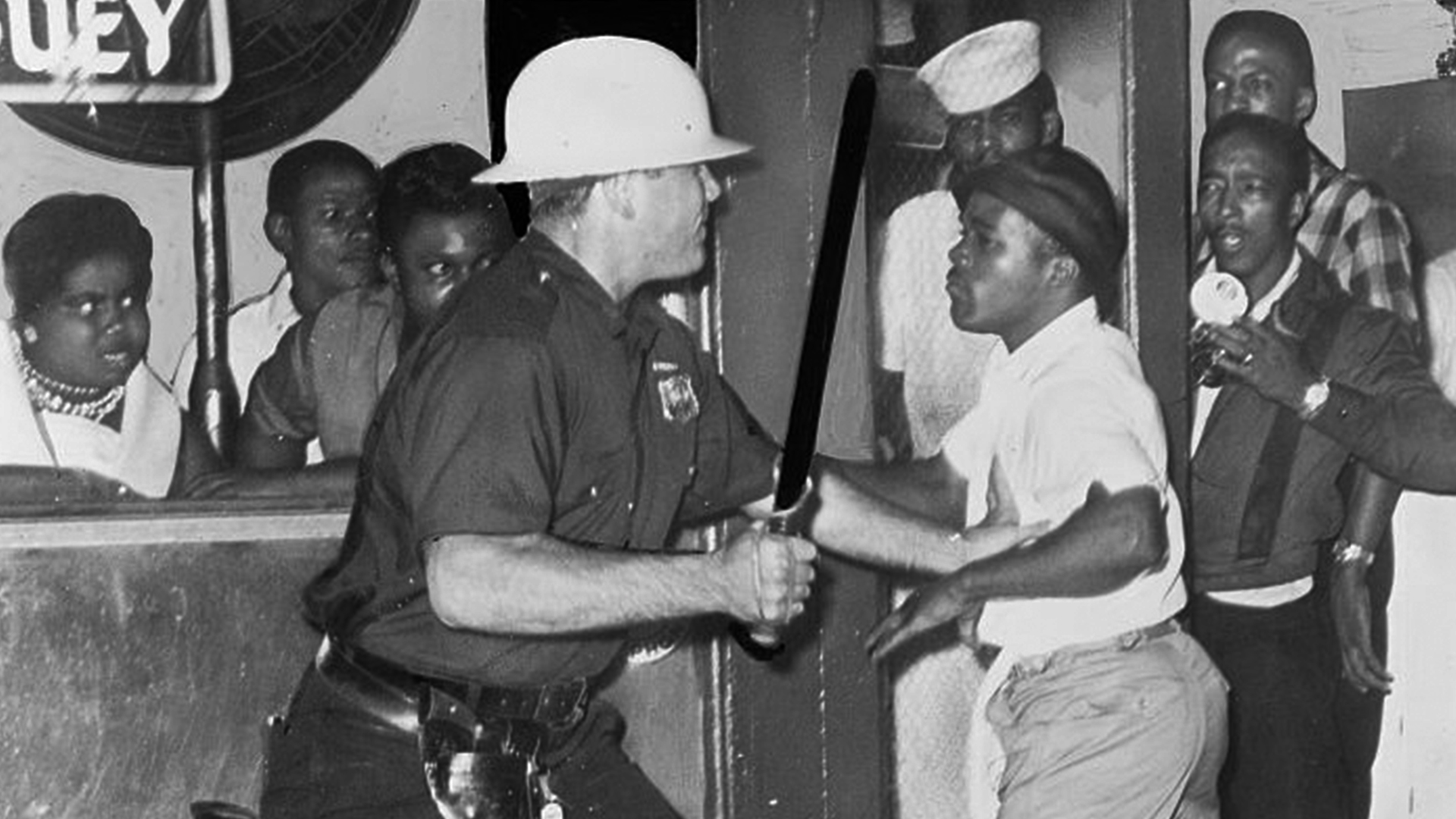

Myra McNair: So, we had some of the older clinicians say, “This is really bringing up the ’60s for me. I’ve gone through this. This isn’t new for us.” Right? They were really coming in and schooling us younger people. “We’ve gone through this.”

Angela Fitzgerald: This is how we made it through.

Myra McNair: Yeah. We have clinicians from LA, and they’re like, “I remember the LA riots and Rodney King, and I was right there. That was my community. This is bringing up a lot.” We have clinicians, also, that are from Minneapolis. I’m from Minnesota. We have a couple that are from Minneapolis, and they’re looking at all of the different things that were happening in Minneapolis, and they’re like, “Wow! My school was right by this,” or, “I remember this certain gas station is not there anymore.” There were so many different levels of processing within our community, just even at our clinic.

Myra McNair: Now, you imagine what that shared experience was for all of us in the United States, for Black people. I mean, it was just huge on our mental health, just huge. Then being that we couldn’t gather together for healing spaces that we normally would when these kind of things happen. Right? So, a lot of people in our community leaned to us for that mental health care, for that communication. Just to have someone to connect with and process with.

Angela Fitzgerald: I love everything that you just said, especially, too, the mindfulness that you brought to your staff. Because there’s so often I’ve talked to Black professionals in this city alone, who are like, “I have to figure out how to put on the face when I join my Zoom call, because I’m dealing with so much. But because this experience is not shared amongst my coworkers, I don’t have a space even to process at work. So, I have to file it away, do what I have to do to make it through the day, and then hopefully I have another safe space outside of the workday.”

Angela Fitzgerald: But the fact that you’ve embedded that, because you’re like, “We get it. We’re not only supporting our community, but we are part of the community, and are being impacted, as well. How are we taking care of ourselves, so that we’re in a position to be of support, and to provide that.” Because you’re right. Being in a pandemic, we can’t all come together like we normally would. So, what does that look like now? How is that different? So, I love that you are attentive to that in a way that, I think, that, perhaps, other people might not have been as thoughtful around.

Myra McNair: Yeah. One thing that we did just recently, and throughout the summer, and now through the fall, different organizations, corporate organizations within our community, asked us to run groups.

Angela Fitzgerald: Oh, wonderful.

Myra McNair: Because Black and Brown people were saying, “We need some support here.”

Angela Fitzgerald: Yes.

Myra McNair: And, “We need it at the workplace.”

Angela Fitzgerald: Yes.

Myra McNair: So, we came in and we did real cultural-specific groups for Black and Brown people. One thing I would say, throughout all the organizations, everyone said, “You know what? We’re really glad COVID actually is happening right now, because this would be really hard for me to go into work, with all of my white …”

Angela Fitzgerald: Like physically to go into work.

Myra McNair: Yeah. To physically go in with all of my white counterparts. Right? Go back to work after the murder of George Floyd, after all of the things that have happened in Kenosha, things that have happened in Atlanta, things that have happened in Texas. I mean, all around, that we’re hearing things. It’s just really interesting that it’s been, really, a similar narrative from everyone, of not really understanding, “Who can I trust when I go back to work?” Right? “I actually feel really safe being at home right now.”

Angela Fitzgerald: Wow.

Myra McNair: “Because of all of the racial things that are happening, this is probably the safest place for me right now, is to just be at home.” That’s not a good thing. That’s not… It shows you that as Black people within our community, that we don’t feel safe.

Angela Fitzgerald: What do you think are the effects of our being inundated by the media with images of Black death, whether it’s George Floyd, him being kneeled on his neck until he suffocated, Black men being shot, whatever the case may be? On the one hand, those images are put out there to kinda force, to propel, people to care.

Myra McNair: Yeah.

Angela Fitzgerald: But for those of us who already care, it could be a lot. So, what are you seeing or hearing that you think is a reflection of that impact of those images?

Myra McNair: Yeah. It’s a huge impact. I would say the hugest is it’s really a trauma response that’s happening within a lot of Black people that are seeing these videos, and they’re being shared over and over and over again. For a lot of people, sometimes people don’t even know that they’re opening it, or they’re about to watch a video like that. I talked to one of my other colleagues in DC, who’s actually a clinician. She was so traumatized over Tamir Rice, and she didn’t know what she was about to watch, and literally, those images just kept replaying over and over, of Tamir Rice, and just how young he was, and being a mom, and having a son, it’s just a trauma response.

Myra McNair: So, I tell a lot of people to really try to take a step back and take social media breaks, because sometimes you don’t know that you’re opening these things, or you’re about to see a video like that. I get that they’re needed sometimes for education, but I would say right now, we’ve seen enough. Right? Now I think we need change to really happen, but it’s really hard, I think, for Black people to really just be exposed to that kind of trauma. It’s not new, unfortunately. This trauma is not new. These type of traumas have been within our communities, really, since slavery. Right?

Myra McNair: We talk about lynching, and now it’s just a different form of it. It’s shooting. Right? But it’s not helpful to our mental health at all. We know these things happen within our communities. So, I really … I think the best thing, really, is if our nation could change. Right? And these things don’t repeat themselves.

Angela Fitzgerald: Yeah. That does feel like the frustrating thing, the need for this to continue, because that was Emmett Till’s mother’s, her whole reason for having an open casket funeral for her son. We’ve all seen the images of what he looked like. Was to show, “This is what you’ve done. This is what we need to change.” But we’re still then feeling the need to show these images to encourage that same line of thinking. It becomes frustrating. Like you said, it has a super negative and triggering impact. On the flip side, I see some folks who are opting out of so closely following certain headlines, and instead, trying to put out funny content or other things, being criticized for not focusing on the issues at hand. They’re like, “I need a break. I cannot take this in 24/7.”

Myra McNair: Right.

Angela Fitzgerald: So, what do you say to those who are like, “Yes. Let’s pivot. Let’s present some joy in the midst of what we’re seeing,” as some very, very violent, very graphic images, representations, of themselves, potentially.

Myra McNair: Yeah. I think it’s a balance. Right? Because I think I have a younger daughter. She’s 18. Just turned 18. For her, when she saw a lot of her friends, who were white, from high school, start just posting things about cooking and other things like that, she was really offended. She really felt like, “Our whole community is hurting, and we’re grieving, and you’re carrying on like nothing even happened.” Right? So, I think there’s a balance. I think for Black people, it is great. I have posted, myself, about restoring the joy, restore Black joy, and finding ways to take care of ourselves, finding ways to have joy in the middle of pandemic. I would say pandemics, for us.

Angela Fitzgerald: Yes. Multiple.

Myra McNair: Is really important. So, I think it’s a balance. I think that to use our social media platform for those different things, but I think, also, to remind ourselves that we are human, and we need joy.

Angela Fitzgerald: Yes.

Myra McNair: We need peace. It’s so hard for us, I would say, so much more hard, harder, because we have, yes, COVID, but then we have all of the other things that come with the systemic racism in our nation, as Black people. So, it’s not so much just being Black, but it’s all of the racism that we have to deal with that makes it so hard to find joy, and to find peace. Taking those social media breaks is so important. And if you… I always say people have this little COVID bubble. Right? So, whether you’re single, whether you have a partner, whoever your COVID bubble is, usually it helps just to spend time with actual people, and to get off of social media here and there. You need a balance during this pandemic. It’s so important.

Angela Fitzgerald: That’s a great point, because it can get easy to get sucked in, because you’re at home, and the other outlets that you might have sought out, instead of going online, aren’t there. So, you’re right. Taking those intentional breaks, even from screen time, just for your eyes. Right?

Myra McNair: Yes. Yes.

Angela Fitzgerald: From that point, but also because of all of the things that you’re being inundated with. Because like you mentioned, the structural racism didn’t just stop because of George Floyd and others’ deaths, and because of COVID. So, you have all the things that were already there on top of what’s being layered on those existing issues. Taking are of self, I would say being an intentional act.

Myra McNair: Absolutely.

Angela Fitzgerald: There’s an account I follow on Instagram. Their focus is naps.

Myra McNair: Yes!

Angela Fitzgerald: They see naps as a revolutionary act for Black people.

Myra McNair: It is!

Angela Fitzgerald: They’re called the Nap Ministry, and I follow them, because …

Myra McNair: I follow them, too! I love them! I love the Nap Ministry. Yes.

Angela Fitzgerald: Yes. I’m like, “I’m a believer in naps, as well!” Because that’s self-care.

Myra McNair: Yep.

Angela Fitzgerald: So, in whatever ways people can take care of self. That’s so key. So Myra, you’re in your profession because you recognized that this is an issue. Mental health support is an area of need in the Black community, and you wanted to take part in contributing to that need. So, if can elevate that to what is happening currently with one of the pandemics, around race relations, and how from the Black community seeing all of the Black death that we are surrounded by, and issues with police brutality, et cetera, there are those who might feel like, “I need to do something.”

Angela Fitzgerald: Then there are people outside the Black community that are looking to us as the solvers of an issue that, honestly, we didn’t create. So, for those of us who feel as though, “I am personally impacted by what’s happening,” while at the same time, feeling this compelled to do something, feeling this call to action placed on me, that has to be draining. That has to do something to us. So, what do you say to that?

Myra McNair: Yeah. I would say it’s really hard. Right? It’s a really huge impact on our mental health, because we don’t get a chance to pause and heal. I think it makes sense, because we can’t really fully heal, when we’re talking about a whole shared experience, we’re talking about a collective healing. We can’t really do that until there’s some type of change. So, I think it’s really a human instinct to want to say, “Okay. Well, we’ve got to solve this problem.” Even if we didn’t create the problem, we have got to help, or create some type of change, for the next generation.

Angela Fitzgerald: Exactly.

Myra McNair: Right? There can’t be a healing if this keeps happening. Right? Because then we’re going to try to heal, and then there’s something else that happens, and then we try to heal, and then something else happens. Right? So, it really does make sense. We’ve got to get to the root of this issue, and then our collective healing can come about. But it doesn’t make it easy. Right? I think it creates a lot of toxic stress. I always say that toxic stress causes a lot of inflammation in our body, which then causes a lot of other health issues. I think that’s why we’re also seeing a lot of issues within our community with health, as well as mental health, too.

Angela Fitzgerald: Whew. So, it’s just managing that, maybe, expectation of even though, yes, you want to solve this for your own children, for generations to come, that the approach may need to be managed to not create those other sorts of health problems that you’ve mentioned.

Myra McNair: I think, again, it goes to balance. Right? And creating this balance, and making sure that we are making things better for our next generation, as much as we can, and as much as we have the power to do so, but I think, also, we do have to push back within the white community. Right? And say that, “You really need to create change. This just can’t be on Black people. We didn’t create this system. We didn’t create racism.” Also, us letting white people in on some of the movements. Right?

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Myra McNair: Because knowing that this just isn’t our movement, this has to be all of our movement. Right?

Angela Fitzgerald: Yes.

Myra McNair: This change has to be with all of us.

Angela Fitzgerald: Yes. Historically, that has happened. Right?

Myra McNair: Yes.

Angela Fitzgerald: Where there were white people who took part in the Freedom Rides, for example, and lost their lives alongside those who were Black that were a part of that movement. So, absolutely, this is not just our issue. Right? It’s all of our issue. We didn’t create it, but we need everyone involved to help solve it.

Myra McNair: Creating change happens on a lot of different levels. I tell a lot of parents, “Sometimes the biggest change, and the most revolutionary thing that you can do, is just playing with your kids,” which I know sounds really crazy. Yeah. In a pandemic, during racial unrest, letting our kids in the next generation have joy is not what society is telling us right now. So, that’s why I say it’s revolutionary to just love each other, love our families, love our kids. That is creating huge change. I tell people, “You may not be a protestor, because maybe you’re with your kids, or you can’t just drive to the next city and protest with them, because you’ve got to get your kids to bed on time for their virtual school lesson the next day.” That is revolutionary! That is creating change in your own small way.

Angela Fitzgerald: I love that. Reframing what revolutionary acts are.

Myra McNair: Yes.

Angela Fitzgerald: Because you’re right. Protesting, marching, all of those acts are appreciated, but for those who can’t do those things, for whatever reason, what can you do that still speaks to self-care, love, joy, all the things you’ve mentioned?

Myra McNair: Yes.

Angela Fitzgerald: Whew. Okay. So, I have another question for you. For people who were formerly like myself, who are on the fence about pursuing therapy, because as you mentioned before, even understanding that there is an issue psychologically is sometimes lost on us, because we’re never exposed to, “This is what anxiety looks like. This is what depression looks like.” We may call it something else. I very specifically remember experiencing a panic attack in school years ago, and I didn’t know what it was. I thought I was having a heart attack at … I was maybe 22? I went to the ER at the time, in the city that I lived in, and they asked me if I used cocaine. I was like, “I’ve never used drugs in my life! No!”

Angela Fitzgerald: So, they were like, “Well, we don’t understand why someone your age would be having a heart problem.” They never asked me about school. That eventually came out. They were like, “Okay. You’re a student. So, this is probably why.” But that didn’t click to them to ask me before they asked the drug question. Right? It didn’t click to me that that was probably a connector. So, even after having that issue, it didn’t register, “Oh, I should probably talk to someone.” Now, 10 plus years later, I now have a therapist relationship. But for so long, because, I think, the influence of the church, praying things away, as well as just not seeing myself as having a high enough need to go talk to someone, all those things kept me from having a relationship that, I think, would have been super helpful.

Angela Fitzgerald: Who knows where I would be now, had I had a 10 plus year foundational relationship with a therapist? So, in saying all that, what do you say to people who recognize that, “Yeah. Life is tough. I get stressed sometimes. But everyone’s stressed,” you know… or, “Everyone has these issues.” What would you say to them to, maybe, encourage them to consider that, yes, you’re stressed, yes, everyone’s stressed, but a therapist relationship could also be beneficial to you?

Myra McNair: Yeah. I would say whether it’s big or small, everyone can benefit from seeing a therapist, seeing a counselor. No doctor would ever say, “Wait until you’re having a lot of issues before you come in for check-up,” or, “We want you to come in when you’re having a heart attack. That’s when we want you to come into the hospital.” No. No doctor would ever say that. Right?

Angela Fitzgerald: Hopefully. Yes.

Myra McNair: So, I would say the same thing for families, for individuals, to come in and seek help, seek support, even when you don’t think it’s that big of an issue. That narrative that we tell ourselves, of what is big or not, also comes from your upbringing. Right? So, someone else could think that is really big, or you could look at someone else and compare yourself to someone else, and say, “No. That’s a big issue.” Right? So, normalcy is all what we think it is, based on our upbringing, based on what society or our own community has told us.

Myra McNair: Sometimes when we go in and see a therapist, we get a different perspective. Someone could say, “No. That is really stressful.” Sometimes it shocks people. “Wow! It is? I didn’t realize I was walking around with this stress, or I was walking around with this issue that I just thought I was supposed to have it.” Right? Because we were taught that it was normal, or, “This is what I’m supposed to be dealing with.” Maybe you saw a parent that really had a lot of anxiety. Sometimes we pick up on those things from our parents, and we don’t even know that. We just think, “Well, I thought that’s how I was supposed to feel, or everyone walked around stressed like that.” Right?

Angela Fitzgerald: Exactly.

Myra McNair: So, I think it really gives perspective. It creates a better you. That’s different for everyone.

Angela Fitzgerald: I will say, for those who are watching this, who either might be in the camp of, “I am not a part of the Black community, but I’m learning a lot, and maybe I would like to support in some ways,” or those who are part of the community and are like, “Wow. You’ve highlighted some areas that I didn’t think about,” or, “You’re just really resonating with me,” what would you like the takeaway to be from this conversation? For either audience.

Myra McNair: I think just having empathy. Right? Having empathy, having understanding. I always love that saying, “When you know more, you do better.” Right? I just think knowledge, and just being able to listen, and to understand that we don’t know and understand everything, and to listen to one another. Right? I think it’s huge. I think empathy right now in our country is just so needed right now. I think that was, for me, when the murders of George Floyd, and then of so many other, during a pandemic, when so many people are hurting, physically, financially, people are in isolation, the only thing I can think of is, “Where was the kindness? Where was the empathy?”

Myra McNair: We’re in the middle of this foundation of this pandemic. Right? I think we just need more of that. So, I think that would be the one biggest takeaway. I think one thing, too, with us, we’re doing a lot of telehealth. Right? We’re doing mostly telehealth because of the pandemic. Therapy’s in real closed spaces and in closed offices, where it’s like, “Yeah. We can’t open windows, even when it’s nice, because there’s confidentiality issues.” So, that has been a huge barrier during this pandemic. We have lost clients because we serve so many different people from different socioeconomic backgrounds. So, some have been homeless. They don’t have phones. They don’t have internet. So, how can people access really great mental health care in a pandemic when it’s all about resources? Needing internet, needing something to actually use. Right?

Angela Fitzgerald: Right. A device of some sort.

Myra McNair: Yeah. Some kind of device. So, we did write a lot of grants that were turned down, actually, over the pandemic, because right now people are really seeing the need of eviction prevention and food.

Angela Fitzgerald: More basic resources. Yeah.

Myra McNair: More basic resources, and mental health is still forgotten about. Even though people are talking about mental health during this pandemic, it is still really low on the priority list. So, I just ask people to just be really mindful of this being a real basic need, especially during the pandemic, for all ages.

Angela Fitzgerald: Thank you for uplifting that issue, because you’re right. There are all of these other needs that are being highlighted and mobilized around, but then if that is the underpinning behind these other areas that you’re focusing in on, then you’re not quite hitting the mark. So, I absolutely love that. Whew. So, there’s still more work to be done.

Myra McNair: Yes.

Angela Fitzgerald: But it sounds like there’s still hopefulness within the midst of the challenges.

Myra McNair: Absolutely.

Angela Fitzgerald: Which I appreciate, which has always been at the core of our community.

Myra McNair: Yeah.

Angela Fitzgerald: Thank you so much, Myra.

Myra McNair: Thank you.

Angela Fitzgerald: Negative messages and images associated with being Black is honestly exhausting. On top of dealing with trauma, many within the Black community also are tasked with leading the charge on social justice. This daily struggle is devastating for Black mental health. That’s why race matters when we talk about it. But there are ways to find help, people, like Myra, willing to listen, and remind us that finding joy is a revolutionary act. For more info on Why Race Matters, and to hear and watch other episodes, visit us online at pbswisconsin.org/whyracematters.

Speaker: Funding for Why Race Matters is provided by CUNA Mutual Group, Park Bank, Alliant Energy, Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Focus Fund for Wisconsin Programming, and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

Photo/Library of Congress/Dick Marsico

Resources

Access a collection of mental health and support services available in the state, crisis intervention resources, online mental health resources, and ways to celebrate Black joy.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us