Announcer:

The following program is a PBS Wisconsin original production.

Frederica Freyberg:

Congress keeps the budget knives sharp, carving away at federal funding, while Wisconsin spending choices cast an eye toward the bright lights of Hollywood.

I’m Frederica Freyberg. Tonight on “Here & Now,” Democratic Congresswoman Gwen Moore talks taking back the House in the midterm elections. Our series “Rx Uncovered” looks at health plans that aren’t actually health insurance. And the state budget clears the way for Hollywood to light up Wisconsin with film maker tax credits. It’s “Here & Now” for July 18.

Announcer:

Funding for “Here & Now” is provided by the Focus Fund for Journalism and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

Frederica Freyberg:

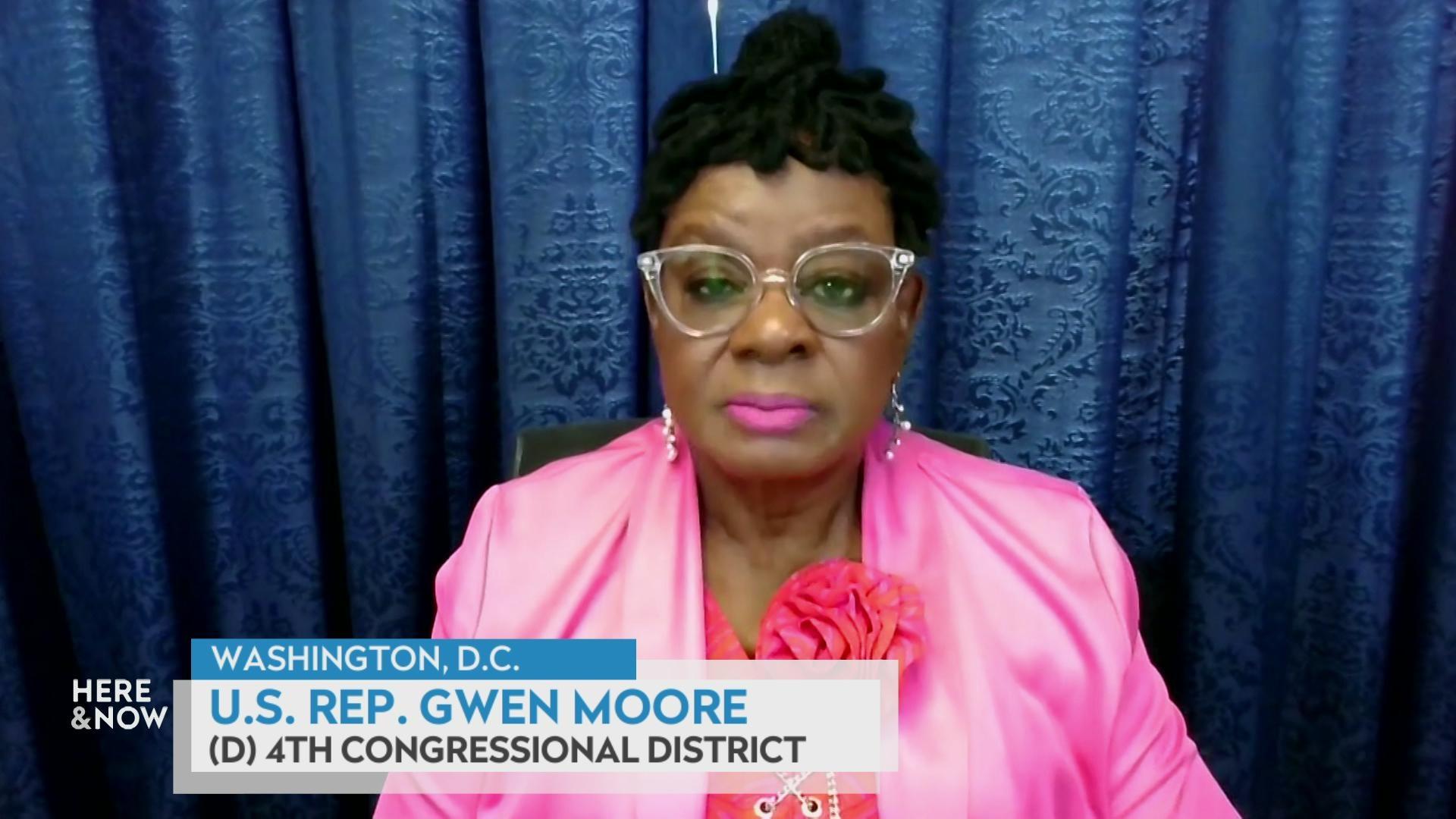

The dust is settling after passage of the federal tax and spending reconciliation bill, which is now law. What stands out for its impact in Wisconsin? We turn to Democratic U.S. Representative Gwen Moore of Milwaukee for her take on what it means for people in her district. And thanks so much for being here.

Gwen Moore:

Always good to be with you, Frederica.

Frederica Freyberg:

So what does stand out for its impact in your district and across Wisconsin?

Gwen Moore:

Well, I think the thing that is most outstanding in this bill is the impact that will have on health care, on the Medicaid cuts, BadgerCare, as we call it in Wisconsin, the Affordable Care Act, ObamaCare cuts. And when you combine the work requirements to receive Medicaid and when you — the confluence of all those forces means that they’ll probably be something like 276,000 people in Wisconsin who will not receive any kind of health care. And when you just — just the work requirements themselves will cost 68,000 individuals with no dependents to lose health care. And so the theory of the case is that these are just lazy boys in their mama’s basements playing video games, and there’d be no harm and no foul to cut them off. Notwithstanding the fact we don’t — we believe this is not a real person. This is just a trope. We’re saying that in Wisconsin, a person who, say, has two minimum wage jobs working at fast food restaurant, they will — at minimum wage, working full time – they will make too much money to be eligible for Medicaid. So they’ll be — whether they work or not, they won’t receive Medicaid. And then there are numbers of people who are truly eligible. They have children. They’re already working. Most people who receive Medicaid are already working, but the numbers of the bureaucracy and the paperwork that they have added into the bill is really something that they have monetized. They have monetized people’s mistakes so that if you don’t re-up or come in every six months to reconfirm that you’re still disabled, or that you will find yourself off Medicaid, and then those of — you remember Frederica, Wisconsin was one of those states, I believe it was about 11 states that hadn’t taken advantage of the expansion of the Affordable Care Act. And those people will see their premiums go eight, nine times the amount that they’re currently paying. So say, for example, they were able to get a silver plan. And for the purposes of keeping the math simple of $100 a month. They might find themselves with six, seven, $800 a month. We are thinking that the food share cuts, SNAP cuts. Not only will it cost thousands, hundreds of thousands of people to be cut off food share, but it will also mean that the state itself would have to pay 75% of the administrative costs of the of the food stamp program, the SNAP program, as well as if there are — an error rates in excess of 6%, they’ll find themselves having to pay for portions of the food stamp program, which to date that burden has never been — an unfunded mandate that will be placed on not only Wisconsin, but statewide. So it is really a bad bill.

Frederica Freyberg:

People who fall off of Medicaid because of the provisions of this bill and potentially the burdensome kind of paperwork, what will they do for health care then?

Gwen Moore:

That will increase the amount of uncompensated care that hospitals have to pick up. And it also means that hospitals will have to make decisions about what kind of health care they will or will not provide. We’ve seen in the past, just recently, in our own community, maternity wards, closing. Where hospitals will decide we aren’t going to do cardiac catheterizations anymore. One of the things is, is that, you know, the president predicts that people won’t even pay any attention. They won’t even notice. Some of these provisions don’t come into effect until after the 2026 election. But that doesn’t mean that hospitals won’t have to start planning how to not deliver services now.

Frederica Freyberg:

We know that the Trump administration is apparently making good on its promise to dismantle the U.S. Department of Education. And with it, as you suggested, funds that go to high poverty K-12 schools and special education. How pointedly will that be felt in Milwaukee?

Gwen Moore:

Oh my God. I mean, you know, when you think about their raison d’etre that there’s waste, fraud and abuse? I mean that — to cut education is like cutting the lifeline of a community. When you think about preparing the future workforce, I can see it causing employers to flee the state. These Republicans have demonstrated a real distaste for education. I mean, and every, everything from K-12 to higher education, where they’re, you know, conditioning Pell Grants in a way that’s never been done before. Cutting off those — the ability for parents to borrow money to send their kids to college. It is like a really big mistake that’s going to put not only Milwaukee, but the nation behind.

Frederica Freyberg:

You’ve said that there “is truly no bottom to this bill’s cruelty,” but what can you and other opponents do about it?

Gwen Moore:

Well, you know, Frederica, I, you know, I, I, you know, I did, I did not have a good 4th of July. I was very, very upset. But you know what? It ain’t over until it’s over. I think now, as we go through this process, we are going to continue to talk about it. We’re going to continue to try to win the midterm elections, win the hearts and souls and minds of people. I know I’ve talked to several people who confess to me that they voted for Donald Trump, but they had no idea that that he was going to do the kinds of things that he has done to them, because indeed, the president’s base needs Medicaid almost more than anybody. The president’s base needs SNAP. And they certainly need educational opportunities. They’re not, you know, and I think that many people who sort of thought that he was going to focus on throwing out violent criminals who were immigrants and they were going to get rid of the waste, fraud and abuse. And of course, nobody wants waste, fraud and abuse. But no one knew that, that all these cuts were just going to result into a big bonanza. You know, $4.5 trillion for wealthy people who don’t really need it. While there are debates about whether or not we should serve breakfast and lunch to school children. Nobody knew that that was a tradeoff.

Frederica Freyberg:

Congresswoman Gwen Moore, thanks very much for joining us.

Gwen Moore:

Thank you. You be well, Frederica.

Frederica Freyberg:

Thank you.

Next week we speak with First District Republican U.S. Representative Bryan Steil.

As to congressional action this week, both the House and Senate voted to rescind funding already appropriated for the next two years to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. That’s a $1.1 billion cut to PBS and NPR. PBS Wisconsin is a member station of PBS.

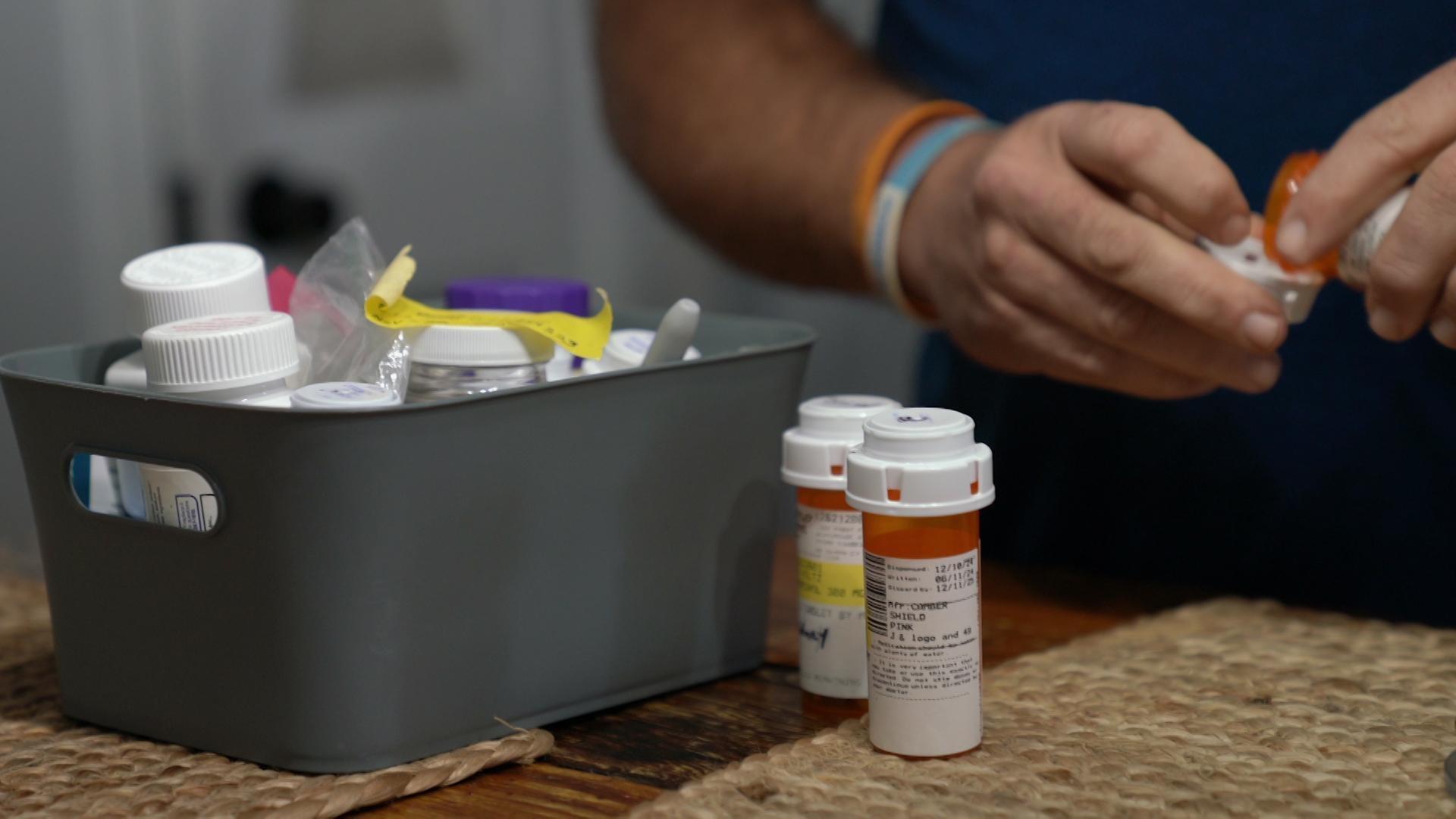

We turn now to our continuing coverage of prescription drugs, where the cost for patients continues to skyrocket as health coverage for critical medication declines. In “Rx Uncovered,” “Here & Now” producer Marisa Wojcik examines the complex systems driving these trends and the stories of patients facing life or death choices. Our next story is about a leukemia patient who had a promising treatment that cost the same as buying a house, and he couldn’t access it without paying upfront.

Kevin Voltz:

All of a sudden, my numbers were at like 167,000, compared to like 4 or 5000.

Marisa Wojcik:

Kevin Voltz has what’s called chronic lymphocytic leukemia or CLL, a type of blood cancer. He was suddenly in urgent need of treatment.

Kevin Voltz:

My cancer center. I can’t say enough about them.

Marisa Wojcik:

His oncologist had a prescription that was promising, but it came at a price.

Kevin Voltz:

$13,000 before we could ship this. And I said $13,000. Yes. That’s what this drug costs to be delivered without insurance.

Marisa Wojcik:

He soon discovered his health plan wouldn’t be covering a dime of his medication, calling it a non-preferred specialty drug and putting him on the hook for 100% of the cost.

Kevin Voltz:

Nobody could do that. I don’t care who you are.

Marisa Wojcik:

This specialty drug costs $13,000 per month. It’s a non-chemotherapy treatment and the first FDA approved medicine for people with a high-risk form of CLL with no generic equivalent.

Kevin Voltz:

I got lots of denial letters and stuff over the months saying that there was nothing they could do. And I’m running low on my month’s supply and what am I going to do next month?

Marisa Wojcik:

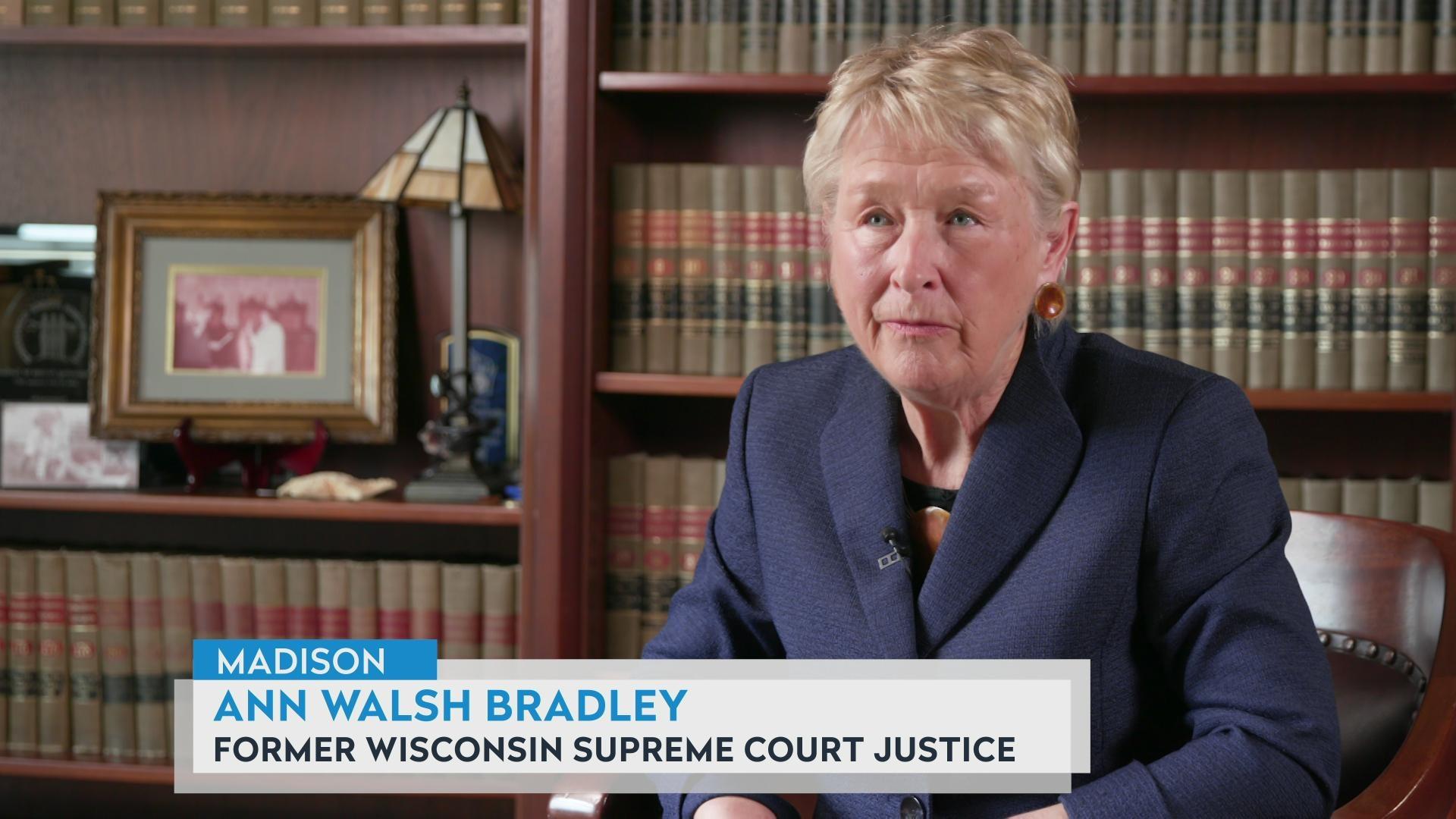

His clinic pleaded with his health plan to cover some portion of his life-saving medication. Under the Affordable Care Act, health insurance plans have cost sharing requirements and limits to what a patient has to pay out of pocket. Covering prescription drugs is considered an essential health benefit. However, Kevin’s health plan doesn’t fall under the ACA because it’s not technically insurance. Instead, his health coverage through his employer is what’s called a self-funded plan. These plans are also known as self-insured, which is a bit of a misnomer.

Kevin Voltz:

We don’t cover that because we’re a self-funded insurance company.

Sarah Davis:

A self-funded plan is not insurance.

Marisa Wojcik:

Sarah Davis is the director of the Center for Patient Partnerships, a research and advocacy program at UW-Madison.

Sarah Davis:

Being insurance

is what triggers state regulation, and there are rules those companies need to follow, in terms of mandatory benefits they need to cover, right? If there are claims being denied, the protections that that consumer has are reduced in self-funded plans.

Marisa Wojcik:

Today, self-funded plans are the most predominant form of health coverage in the U.S. because they help employers save money.

Mike Roche:

Self-funding lets the employer take control of the second or third biggest line item on their budget.

Marisa Wojcik:

Mike Roche is the director of business development at the Alliance, a Wisconsin organization that helps employers design self-funded health plans.

Mike Roche:

If you’re, if you’re not trying to manage it and you’re fully insured, you’re going to get an increase probably every year. The last few years, that’s been a double-digit increase. And it’s getting more and more difficult for employers to find a way to control that cost.

Marisa Wojcik:

Making it difficult for employers to afford health coverage.

Sarah Davis:

The reason that self-funded plans came about is that employers realized they were paying a fixed amount to the insurance company, and then it was the insurance company that, while holding the risk, could make the profit. And so employers realized, hey, if we hold all that money ourselves and only pay a certain percentage in claims, we’re keeping that profit. The concern I have as a health advocate is that a large motivation for having a self-funded plan is to save money, and the place that the money is saved is in paying out less claims.

Marisa Wojcik:

A recent study shows the top issue for Wisconsin businesses is to make health care more affordable. That same study says the majority of people in Wisconsin are very worried about their cost of health care.

Mike Roche:

Knowing that your self-funded and that there’s value to be found. If you, as the employee, are good stewards of the plan and seek value, that should have a trickledown effect so that the next year you don’t see your part of that premium go up. You may not have to change deductibles or co-insurances so you can get some stability in your plan.

Marisa Wojcik:

But it’s often difficult for people to even know what kind of plan they have.

Sarah Davis:

It takes advocates and patients sometimes quite a bit of time to parse out and figure out that it is not insurance.

Mike Roche:

A lot of it comes back to transparency. What employees need to know is that your employer has now become the insurance company. You know, whether you’re fully insured or self-funded, that plan doc is the same. I think as long as an employee understands the high-level pieces of their plan design: deductibles, co-insurances. What’s on their formulary list from their PBM? Who’s in network from a doctor or hospital standpoint? That’s going to cover 95 to 98% of everything they do during the year.

Marisa Wojcik:

So who pays for the big-ticket items?

Mike Roche:

You know, there’s a couple of drugs coming out. They’re going to be $3 million apiece. How am I going to cover those? And how does that trickle down to the Humiras and the Stelaras that folks need on a more regular basis, but are still, you know, thousands of dollars a month?

Marisa Wojcik:

Advocates Marisa Wojcik say self-funded plans can create a conflict of interest for employers who suddenly have an employee with expensive health needs.

Kevin Voltz:

Maybe you could check into going part-time and see if Medicare or something would help out. And I thought to myself, really? You want me to go part time. Now I’m going to lose benefits. I’m going to lose my insurance, and I’m going to be part time. Is this a way to weed me out eventually?

Sarah Davis:

In an insurance situation, right, the employer wants to protect the employee, right? They want to get the most for their money. Once we’re in a self-funded situation, the employee is at odds with the employer.

Marisa Wojcik:

The side effects of dealing with it all took a toll.

Kevin Voltz:

One day I sat on my phone on hold from one of the drug companies for over six hours. Just stressing me out to the point where I was not paying attention to my healing.

Marisa Wojcik:

Advocates at his clinic didn’t let up.

Kevin Voltz:

They’re very persistent, very persistent.

Marisa Wojcik:

Exhausting every possible avenue to access his medicine. After months of setbacks, good news arrived from his clinic.

Kevin Voltz:

She kept calling me and calling me and calling me. She couldn’t tell me the news fast enough that they had come through.

Marisa Wojcik:

The drug manufacturer said they were going to provide the remaining dose of his treatment at no cost.

Kevin Voltz:

I don’t think anybody should have to fight for their life like that. It’s hard enough just to sit back and think about me not being here for the people around me. I worry about not being here. Normal, I guess.

Sarah Davis:

I worry for people who don’t have hours and hours and hours to read fine print and you know, make sure that they’re going to get what they need if, you know, if they get ill.

Marisa Wojcik:

In the end, Kevin hopes some good will come from his experience.

Kevin Voltz:

My dad died from CLL several years ago. Even after he would go and have spinal taps and stuff, he always said if they can learn something from my treatments for the next people, I’ve accomplished something in life. I say the same thing. If they can get something out of me for other people, I’ve done exactly what I wanted to do in life.

Marisa Wojcik:

Reporting from Palmyra, I’m Marisa Wojcik for “Here & Now.”

Frederica Freyberg:

In state budget news from 1987 to 2005, the state had a film office spending millions of dollars to attract blockbuster productions like “Public Enemies” to film in Wisconsin. In a sort of take two, state lawmakers just agreed to fund a new production incentive program. The state budget reestablished the Wisconsin Film Office and offers up to $5 million in tax credits to filmmakers. They’re banking on more Hollywood movie makers and local filmmakers to bring their work to Wisconsin. “Here & Now” reporter Murv Seymour has details.

Nathan Deming:

Thanks everybody for coming. This is such a cool turnout. Let’s talk about bringing Tinseltown to the Chippewa Valley.

Murv Seymour:

On this cool summer evening in the heart of downtown Eau Claire…

Woman:

I’ve been producing, writing, story editing.

Murv Seymour:

… locals passionate about filmmaking have come to the town’s library to learn.

Nathan Deming:

If you make documentaries, you can say that. If you’re an actor, you can say that.

Murv Seymour:

Learn from each other about what they can do to encourage and cultivate more filmmaking projects, large and small, to be made in the state of Wisconsin.

Tim Schwagel:

This turnout is crazy.

Murv Seymour:

Tim Schwagel helps set up for this night of collaborating.

Tim Schwagel:

I think that it says a lot of people care about filmmaking, care about film or art in general. We’re kind of an island where it doesn’t feel like there’s a lot of people that do filmmaking in the area. But as I’ve learned over the years, is that people just kind of appear and you meet someone who’s right in the same town. It’s like, “Oh, you do this too.” So this is kind of the first time that we’ve had an event that brings us all to one spot.

Murv Seymour:

Almost 70 people passionate about filmmaking at all levels are here.

Nathan Deming:

Somebody who’s sold a Netflix movie. Other people who have shown their documentary around the state. Actors, writers. We got Christmas tree farms. We can do Christmas movies here.

Murv Seymour:

Tonight’s event has been organized and is led by Nathan Deming, a Los Angeles filmmaker who splits his time between Hollywood and his hometown of Eau Claire.

Nathan Deming:

Roll camera please.

Murv Seymour:

So far, he’s shot five movies in Wisconsin. He wants to boost local filmmaking and big Hollywood productions in the state. You’re watching a clip from his most recent movie called “February.”

Nathan Deming:

I don’t think anybody, at least in my world, could have predicted ten years ago that we’d be looking at headlines that Hollywood is leaving L.A. I think the new future is that film is going to be everywhere, in the hot spots, and it’s going to be because of things like the film office.

Murv Seymour:

At a time when a movie can be made anywhere, up until now, Wisconsin was one of only three states with no state film office and one of only a few states that didn’t offer financial incentives to help lure productions to the state.

Jeff Kurz:

It is all about money.

Murv Seymour:

Movies are made where there’s free money.

Jeff Kurz:

Production incentives are the number one factor that production companies consider when they decide where to film.

Murv Seymour:

I met with former Miramax movie executive Jeff Kurz inside Independent Studios, a post-production house in Milwaukee that serves large, Hollywood based productions and local ones too.

Actor in movie clip:

I’m going to guess that you’re a pretty important guy in the city.

Murv Seymour:

By choice, Kurz filmed his movie “Deep Woods” and his last two films in Wisconsin.

Jeff Kurz:

Filmmaking is not something that just happens in New York or Los Angeles or Atlanta or Chicago.

Murv Seymour:

Kurz represents a steering committee of filmmakers, business owners, government officials and others who want Wisconsin to compete with neighboring states in luring filmmakers to film in the Badger State by dangling tax breaks.

Jeff Kurz:

When I was having a conversation with somebody in Eau Claire, I said, “Listen, you have a beautiful community. It is picture perfect to make a movie there. But without a film office, there is nobody to tell an out-of-state production how great you are.”

Nathan Deming:

There’s Banbury Place, this crazy factory thing. You know, the rivers, you know, we have so many locations here.

Murv Seymour:

Wisconsin’s revitalized film office will now become part of the state’s tourism department.

Anne Sayers:

We are turning football fans into Wisconsin fans every moment.

Murv Seymour:

We caught up with its leader during the 2025 NFL Draft in Green Bay.

Anne Sayers:

It’s a lot about those people coming into Wisconsin to do the production and building a whole cottage industry around that, but it’s also about setting a perception once it’s on the big screen, that’s also important to the long-term perception of Wisconsin.

Murv Seymour:

In 2024, the hit TV series “Top Chef” filmed in Milwaukee. The show is a highlight reel of Wisconsin culture, cuisine and community that has the entire state cashing in from its worldwide audience.

Susan Kerns:

Because people were seeing this restaurant or that restaurant and then just wanted to go there and try it. All of that is possible as a reverberation from filmmaking, television making. So it’s not just the filmmakers who would benefit from something like that. It’s really the whole state.

Jeff Kurz:

The county of Milwaukee saw an uptick of $1.5 million in hotel room rentals alone from people coming here to see, to see Wisconsin, right, to see what they had seen on television.

Nathan Deming:

New Mexico implemented these and then got “Breaking Bad,” which was not written for New Mexico. It just went there because of tax incentives. And then suddenly, it not only got that, it got “Better Call Saul.” So two hit shows.

Tim Schwagel:

The talent’s here and it’s always a roll of the dice to see if something blows up. But I think it’s easy for us to forget here in Wisconsin that Wisconsin is just gorgeous.

Susan Kerns:

The hills, the trees, all of that. The Driftless Region, gorgeous, and Lake Michigan. So we have all of these different terrains. We have cities like Madison and Milwaukee.

Nathan Deming:

Superior offers 25% film incentive for the city itself, if you stay at their hotels. Right as L.A. is losing jobs and filming, Illinois is exploding. Minnesota is exploding. A city like Duluth, a lot of filming happening on the Duluth side. Nothing on the Wisconsin side. And it’s just because of film incentives.

John Ridley:

There are no dollars that are better than Hollywood dollars.

Murv Seymour:

That’s award-winning Hollywood filmmaker and Milwaukee native John Ridley. When it comes to him or any other large budget film shooting in Wisconsin, he point blank told me this.

John Ridley:

Until Wisconsin gets tax credits, and that’s something that I’ve advocated for, no, that’s not going to happen.

Murv Seymour:

Ridley proudly tells me he routinely shoots smaller projects in Wisconsin.

John Ridley:

But in terms of doing feature films out here, whether it’s myself or anybody else, Wisconsin, I’m going to look into the camera. You got to get tax credits. We’ve talked about this. You got to advocate for tax credits.

Murv Seymour:

Enough said, Mr. Ridley. Lawmakers hear the call for action.

Nathan Deming:

Georgia built a really good film incentive program and brought in a lot of business. And there’s movies now that are set in New York City. But if you watch the credits, there’s going to be a Georgia peach at the end of it. There is zero soundstages in the entire state of Wisconsin. So right now that’s a huge thing that if productions want to film. For the first time in, like, 100 years, the film industry is morphing and we have a real opportunity to pick up the work, just like our neighbors Illinois and Minnesota are doing.

Murv Seymour:

Reporting from Eau Claire, I’m Murv Seymour for “Here & Now.”

Frederica Freyberg:

For more on this and other issues facing Wisconsin, visit our website at PBSWisconsin.org and then click on the news tab. That’s our program for tonight. I’m Frederica Freyberg. Have a good weekend.

Announcer:

Funding for “Here & Now” is provided by the Focus Fund for Journalism and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

Search Episodes

News Stories from PBS Wisconsin

Donate to sign up. Activate and sign in to Passport. It's that easy to help PBS Wisconsin serve your community through media that educates, inspires, and entertains.

Make your membership gift today

Only for new users: Activate Passport using your code or email address

Already a member?

Look up my account

Need some help? Go to FAQ or visit PBS Passport Help

Need help accessing PBS Wisconsin anywhere?

Online Access | Platform & Device Access | Cable or Satellite Access | Over-The-Air Access

Visit Access Guide

Need help accessing PBS Wisconsin anywhere?

Visit Our

Live TV Access Guide

Online AccessPlatform & Device Access

Cable or Satellite Access

Over-The-Air Access

Visit Access Guide

Passport

Passport

Follow Us